Variation in Birdsong of Red Vented Bulbul ( Pycnonotus Cafer) Inhabiting Two Different Locations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Employees Details (1).Xlsx

Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services, KALABURGI District Super Specialities ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. Namdev Rathod Assistant Director 08472-226139 9480688435 Veterinary Hospital CompoundSedam Road Kalaburagi pin Cod- 585101 Veterinary Hospitals ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. M.S. Gangnalli Assistant Director 08470-283012 9480688623 Veterinary Hospital Afzalpur Bijapur Road pin code:585301 Assistant Director 2 Dr. Sanjay Reddy (Incharge) 08477-202355 94480688556 Veterinary Hospital Aland Umarga Road pin code: 585302 3 Dr. Dhanaraj Bomma Assistant Director 08475-273066 9480688295 Veterinary Hospital Chincholi pincode: 585307 4 Dr. Basalingappa Diggi Assistant Director 08474-236226 9590709252 Veterinary Hospital opsite Railway Station Chittapur pincode: 585211 5 Dr. Raju B Deshmukh Assistant Director 08442-236048 9480688490 Veterinary Hospital Jewargi Bangalore Road Pin code: 585310 6 Dr. Maruti Nayak Assistant Director 08441-276160 9449618724 Veterinary Hospital Sedam pin code: 585222 Mobile Veterinary Clinics ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. Kimmappa Kote CVO 08470-283012 9449123571 Veterinary Hospital Afzalpur Bijapur Road pin code:585301 2 Dr. sachin CVO 08477-202355 Veterinary Hospital Aland Umarga Road pin code: 585302 3 Dr. Mallikarjun CVO 08475-273066 7022638132 Veterinary Hospital At post Chandaput Tq: chincholi pin code;585305 4 Dr. Basalingappa Diggi CVO 08474-236226 9590709252 Veterinary Hospital Chittapur 5 Dr. Subhaschandra Takkalaki CVO 08442-236048 9448636316 Veterinary Hospital Jewargi Bangalore Road Pin code: 585310 6 Dr. Ashish Mahajan CVO 08441-276160 9663402730 Veterinary Hospital Sedam pin code: 585222 Veterinary Hospitals (Hobli) ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. -

Table of Content Page No's 1-5 6 6 7 8 9 10-12 13-50 51-52 53-82 83-93

Table of Content Executive summary Page No’s i. Introduction 1-5 ii. Background 6 iii. Vision 6 iv. Objective 7 V. Strategy /approach 8 VI. Rationale/ Justification Statement 9 Chapter-I: General Information of the District 1.1 District Profile 10-12 1.2 Demography 13-50 1.3 Biomass and Livestock 51-52 1.4 Agro-Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography 53-82 1.5 Soil Profile 83-93 1.6 Soil Erosion and Runoff Status 94 1.7 Land Use Pattern 95-139 Chapter II: District Water Profile: 2.1 Area Wise, Crop Wise irrigation Status 140-150 2.2 Production and Productivity of Major Crops 151-158 2.3 Irrigation based classification: gross irrigated area, net irrigated area, area under protective 159-160 irrigation, un irrigated or totally rain fed area Chapter III: Water Availability: 3.1: Status of Water Availability 161-163 3.2: Status of Ground Water Availability 164-169 3.3: Status of Command Area 170-194 3.4: Existing Type of Irrigation 195-198 Chapter IV: Water Requirement /Demand 4.1: Domestic Water Demand 199-200 4.2: Crop Water Demand 201-210 4.3: Livestock Water Demand 211-212 4.4: Industrial Water Demand 213-215 4.5: Water Demand for Power Generation 216 4.6: Total Water Demand of the District for Various sectors 217-218 4.7: Water Budget 219-220 Chapter V: Strategic Action Plan for Irrigation in District under PMKSY 221-338 List of Tables Table 1.1: District Profile Table 1.2: Demography Table 1.3: Biomass and Live stocks Table 1.4: Agro-Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography Table 1.5: Soil Profile Table 1.7: Land Use Pattern Table -

Name of the Village

POPULATION PROFILE OF KALBURUGI Dist AS PER 2011 CENSUS Total SC ST Sl No Name of the Village % % Population Population Population 1 Gulbarga 2566326 648782 25.28 65259 2.54 2 Gulbarga 1730775 489697 28.29 50074 2.89 3 Gulbarga 835551 159085 19.04 15185 1.82 4 Aland 342207 85516 24.99 6843 2.00 5 Aland 299836 79777 26.61 6508 2.17 6 Aland 42371 5739 13.54 335 0.79 7 Jamga Khandala 1215 756 62.22 30 2.47 8 Tadola 2568 716 27.88 1 0.04 9 Alanga 2571 281 10.93 7 0.27 10 Sirur (G) 1378 240 17.42 63 4.57 11 Gadlegaon 686 250 36.44 0 0.00 12 Khajuri 6744 912 13.52 9 0.13 13 Jawalga (J) 1707 542 31.75 57 3.34 14 Tugaon 837 222 26.52 27 3.23 15 Annur 1248 295 23.64 69 5.53 16 Hodlur 2697 361 13.39 4 0.15 17 Subhashnagar 1057 1055 99.81 1 0.09 18 Nandgur 500 152 30.40 0 0.00 19 Kotanhipperga 1699 178 10.48 0 0.00 20 Jamga Ruderwadi 1766 502 28.43 0 0.00 21 Rudrawadi 3004 699 23.27 57 1.90 22 Bableshwar 884 228 25.79 65 7.35 23 Bangerga 2334 662 28.36 55 2.36 24 Khandala 1434 528 36.82 141 9.83 25 Nirgudi 3109 307 9.87 87 2.80 26 Matki 4206 732 17.40 291 6.92 27 Teerth 1636 315 19.25 12 0.73 28 Salegaon 2342 506 21.61 135 5.76 29 Chitali 1511 237 15.68 336 22.24 30 Kinnisultan 3322 745 22.43 1 0.03 31 Kanmas 1254 348 27.75 3 0.24 32 Bharked 865 97 11.21 39 4.51 33 Sangunda 1097 279 25.43 4 0.36 34 Belamogi 5127 1613 31.46 189 3.69 35 Karhari 1584 567 35.80 0 0.00 36 Salgera (V.K.) 5182 1734 33.46 137 2.64 37 Lengthi 1956 457 23.36 354 18.10 38 Ladmugli 2636 575 21.81 2 0.08 39 Kalkutga 691 184 26.63 56 8.10 40 Kudmud 1610 806 50.06 0 0.00 41 Ambalga -

1995-96 and 1996- Postel Life Insurance Scheme 2988. SHRI

Written Answers 1 .DECEMBER 12. 1996 04 Written Answers (c) if not, the reasons therefor? (b) No, Sir. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF (c) and (d). Do not arise. RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) (a) No, Sir. [Translation] (b) Does not arise. (c) Due to operational and resource constraints. Microwave Towers [Translation] 2987 SHRI THAWAR CHAND GEHLOT Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state : Construction ofBridge over River Ganga (a) the number of Microwave Towers targated to be set-up in the country during the year 1995-96 and 1996- 2990. SHRI RAMENDRA KUMAR : Will the Minister 97 for providing telephone facilities, State-wise; of RAILWAYS be pleased to state (b) the details of progress achieved upto October, (a) whether there is any proposal to construct a 1906 against above target State-wise; and bridge over river Ganges with a view to link Khagaria and Munger towns; and (c) whether the Government are facing financial crisis in achieving the said target? (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the time by which construction work is likely to be started and THE MINISTER OF COMMUNICATIONS (SHRI BENI completed? PRASAD VERMA) : (a) to (c). The information is being collected and will be laid on the Table of the House. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) : (a) No, Sir. [E nglish] (b) Does not arise. Postel Life Insurance Scheme Railway Tracks between Virar and Dahanu 2988. SHRI VIJAY KUMAR KHANDELWAL : Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: 2991. SHRI SURESH PRABHU -

Nest, Egg, Incubation Behaviour and Parental Care in the Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis Germana

Australian Field Ornithology 2019, 36, 18–23 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo36018023 Nest, egg, incubation behaviour and parental care in the Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis germana Richard H. Donaghey1, 2*, Donna J. Belder3, Tony Baylis4 and Sue Gould5 1Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Nathan 4111 QLD, Australia 280 Sawards Road, Myalla TAS 7325, Australia 3Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia 4628 Utopia Road, Brooweena QLD 4621, Australia 5269 Burraneer Road, Coomba Park NSW 2428, Australia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis germana, recently elevated to species status, is endemic to montane forests on the Huon Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. The polygynous males in the Yopno Urawa Som Conservation Area build distinctive maypole bowers. We document for the first time the nest, egg, incubation behaviour, and parental care of this species. Three of the five nests found were built in tree-fern crowns. Nest structure and the single-egg clutch were similar to those of MacGregor’s Bowerbird A. macgregoriae. Only the female Huon Bowerbird incubated. Mean length of incubation sessions was 30.9 minutes and the number of sessions daily was 18. Diurnal incubation constancy over a 12-hour day was 74%, compared with a mean of ~70% in six other members of the bowerbird family. The downy nestling resembled that of MacGregor’s Bowerbird. Vocalisations of a female Huon Bowerbird at a nest with a nestling -

Parental Care and Investment in the Tooth-Billed Bowerbird Scenopoeetes Dentirostris (Ptilonorhynchidae)

VOL. 11 (4) DECEMBER 1985 103 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1985, 11, 103-113 Parental Care and Investment in the Tooth-billed Bowerbird Scenopoeetes dentirostris (Ptilonorhynchidae) By C.B. FRITH and D.W. FRITH, 'Prionodura', Paluma via Townsville, Qld 4816 Summary The known southern distributional limit of the Tooth-billed Bowerbird Scenopoeetes dentirostris is extended from Paluma (19°00'S, 146°l3'E) to Mt Elliot(l9°30'S, 146°57'E) near Townsville, Queensland. Records of the rarely found nest of Scenopoeetes, clutch size, egg weight, egg-laying and nestling periods are summarised. Systematic observations over 45 hours at three nests strongly suggest, but do not conclusively prove, uniparentalism presumably by females. Data for a single-nestling brood at one nest are compared with similar data for the uniparental Golden Bowerbird Prionodura newtoniana and monogamous biparental Spotted Catbird Ailuroedus melanotis, which provide further evidence in support of uniparentalism in Scenopoeetes. Meagre nestling diet information is summarised. Parental care and behavioural records are reviewed and previous erroneous and confusing reports discussed. • Introduction The Tooth-billed Bowerbird* Scenopoeetes dentirostris is one of the least known of the 18 bowerbird species and is certainly less known than the other eight species in Australia. It occurs in upland rainforests between c. 600 and 1400 m above sea level from Mt Amos (15°42'S, 145°18'£) southward to Saddle Mountain on Mt Elliot (l9°30'S, 146°57'£) just south of Townsville, Queensland, where Dr George Heinsohn (pers. comm.) was attracted to an active court by typical male vocalisations on 13 November 1980. This is an extension of the previously known southern limit of this bird's range of 55 km due south or 90 km to the south-east from the previously recorded location of Paluma or Mt Spec (Storr 1973, Griffin 1974). -

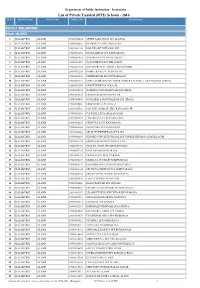

List of Private Unaided (RTE) Schools - 2016 Sl.No

Department of Public Instruction - Karnataka List of Private Unaided (RTE) Schools - 2016 Sl.No. District Name Block Name DISE Code School Name Distirct :KALABURGI Block :ALAND 1 KALABURGI ALAND 29040100204 SHREE SARASWATI LPS ALANGA 2 KALABURGI ALAND 29040100603 JNANODAYA HPS AMBALAGA 3 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101102 MALLIKARJUN HPS BOLANI 4 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101202 JNANAAMRAT LPS BANGARAGA 5 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101408 BASAWAJYOTI LPS BELAMAGI 6 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101409 NAVACHETAN LPS BELAMAGI 7 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101908 MATOSHRI NEELAMBIKA BHUSANOOR 8 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103204 INDIRA(KAN)LPS.DHANGAPUR 9 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103310 VEERESHWAR LPS DUTTARGAON 10 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103311 SHREE SIDDESHWAR LOWER PRIMARY SCHOOL LAD CHINCHOLI CROSS 11 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103505 SHANTINIKETAN GOLA (B) 12 KALABURGI ALAND 29040104105 RAMLING CHOUDESHWARI LPS HIROL 13 KALABURGI ALAND 29040104404 SIDDESHWAR HPS HODULUR 14 KALABURGI ALAND 29040105405 SUSILABAI S MANTHALKAR LPS JIDAGA 15 KALABURGI ALAND 29040105406 SIDDASHREE LPS JIDAGA 16 KALABURGI ALAND 29040105503 S.R.PATIL SMARAK HPS KADAGANCHI 17 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106203 C.B.PATIL LPS KAMALANAGAR 18 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106304 LOKAKALYAN LPS KAWALAGA 19 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106305 CHANUKYA LPS KAWAKAGA 20 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106604 NIJACHARANE HPS KHAJURI 21 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106608 SIR M VISHWESHWARAYYA LPS 22 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106609 OXFORD CONVENT SCHOOL LPS VENKTESHWAR NAGAR KHAJURI 23 KALABURGI ALAND 29040107102 SIDDESHWAR HPS KINNISULTAN 24 KALABURGI ALAND 29040107103 -

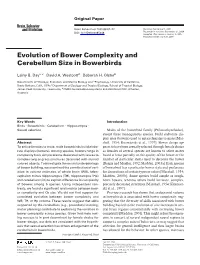

Evolution of Bower Complexity and Cerebellum Size in Bowerbirds

Original Paper Brain Behav Evol 2005;66:62–72 Received: September 1, 2004 Returned for revision: September 21, 2004 DOI: 10.1159/000085048 Accepted after revision: January 3, 2005 Published online: April 25, 2005 Evolution of Bower Complexity and Cerebellum Size in Bowerbirds a–c d b Lainy B. Day David A. Westcott Deborah H. Olster a b Departments of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology and Psychology, University of California, c Santa Barbara, Calif. , USA; Department of Zoology and Tropical Ecology, School of Tropical Biology, d James Cook University, Townsville , CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems and Rainforest CRC, Atherton , Australia Key Words Introduction Birds Bowerbirds Cerebellum Hippocampus Sexual selection Males of the bowerbird family (Ptilonorhynchidae), except three monogamous species, build elaborate dis- play sites (bowers) used to entice females to mate [Mar- Abstract shall, 1954; Kusmierski et al., 1997]. Bower design ap- To entice females to mate, male bowerbirds build elabo- pears to have been sexually selected through female choice rate displays (bowers). Among species, bowers range in as females of several species are known to select mates complexity from simple arenas decorated with leaves to based at least partially on the quality of the bower or the complex twig or grass structures decorated with myriad number of particular items used to decorate the bower colored objects. To investigate the neural underpinnings [Borgia and Mueller, 1992; Madden, 2003a]. Each species of bower building, we examined the contribution of vari- of bowerbird has a particular bower style and preference ation in volume estimates of whole brain (WB), telen- for decorations of certain types or colors [Marshall, 1954; cephalon minus hippocampus (TH), hippocampus (Hp) Madden, 2003b]. -

Novitates No

AMERIICAN MUSEUM NOV ITATES PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CITY OF NEW YORK DECEMBER 12, 1952 NUMBER 1602 GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION AND PLUMAGES IN AUSTRALIAN BOWERBIRDS (PTILONORHYNCHIDAE) By ERNST MAYR AND KATE JENNINGS INTRODUCTION In view of the great recent interest in the biology of bower- birds, it is surprising how little is known about the taxonomy of the Australian species. The available accounts in the standard works are very confusing, since no difference is made in most of them between synonyms and valid subspecies. Furthermore, a study of individual variation, of the sequence of plumages, and of measurements is badly needed, as information on these matters is woefully inadequate in the existing literature. In fact, we know much more about the New Guinea species than about the most familiar Australian birds. The following account is based on the material in the American Museum of Natural History which includes the Rothschild and Mathews collections. Where this material proved inadequate, additional specimens were borrowed from the United States National Museum, the Chicago Natural History Museum, the Museum of Comparative Zoology, and the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (including parts of the Gould Collec- tion). We greatly appreciate the kindness of the curators of these institutions in making this material available. Ailuroedus crassirostris Paykull GREEN CATBIRD The only two Australian subspecies of this Australo-Papuan species are so different from each other that they were listed as 2 AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES NO. 1602 two species in most of the older literature. However, their essential similarity, the agreement of habits, and the basic dif- ference from buccoides (New Guinea), the only other species of the genus, make it evident that crassirostris Paykull, 1815 (=viridis Vieillot, 1817), and maculosus Ramsay, 1875, must be considered as conspecific. -

Field Guides Birding Tours New Guinea & Australia 2011

Field Guides Tour Report NEW GUINEA & AUSTRALIA 2011 Oct 6, 2011 to Oct 24, 2011 Phil Gregory This was a fun and pretty gentle tour with some fantastic birds and good weather throughout. We began as ever in Cairns, where Mangrove Robin was easy (and sans tape), and we saw a fair selection of shorebirds including Terek Sandpiper, Gray-tailed Tattler, Great Knot, and Broad-billed Sandpiper, had Radjah Shelduck still at Centenary Lakes, an unexpected 7-foot saltwater crocodile sunning at the golf course pond, and very nice Lovely Fairywrens. Cattana wetlands gave us Crimson Finch and White-browed Crake on a quick visit. Luck was with us at Cassowary House, where we had the amazing iconic female Cassowary, and Pied, Spectacled, White-eared, and Black-faced monarchs. We then saw almost all the Tablelands endemics including a fine male Golden Bowerbird and nice Fernwren, plus had some unusually good close interactions with foraging Chowchillas. Sadly the Australian Painted- snipe had gone from my friend’s place, but we did score well with Rufous Owl. Varirata was very good: Barred Owlet-nightjar was in the usual hole, and bonus Buff-breasted Paradise-Kingfishers plus Brown-headed Paradise, also Yellow-billed, Variable and Rufous-bellied Kookaburra meant 5 lifer kingfishers for most. Raggiana Birds-of-paradise (BOPs) were right at the end of the season but showed well and were still fairly well dressed, and we got a The Superb Fairywren was indeed superb and a male Growling Riflebird to fly over twice. Gurney’s Eagle being mobbed by trip favorite! (Photo by guide Phil Gregory) what may be my first Peregrines at Varirata was a nice sighting too; a very good day up here. -

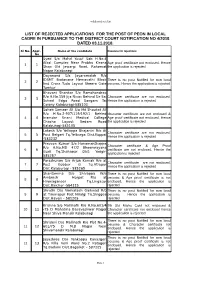

List of Rejected Applications for the Post of Peon in Local Cadre in Pursuance to the District Court Notification No 4/2018 Dated 03.11.2018

webhosted reje list LIST OF REJECTED APPLICATIONS FOR THE POST OF PEON IN LOCAL CADRE IN PURSUANCE TO THE DISTRICT COURT NOTIFICATION NO 4/2018 DATED 03.11.2018. Sl No. Appl . Name of the candidate Reasons for rejections No Syed S/o Mohd Yusuf Sab H.No.4 Afzal Complex Near Prabhu Kirana Age proof certificate not enclosed. Hence 1 1 Shop Old Jewargi Road, Rahemat the application is rejected Nagar Kalaburagi Dayanand S/o Jayaramaiah R/o IDSMT Badavane Hemavathi Block There is no post Notified for non local 2 2 Iind Cross Tuda Layout Sheera Gate persons. Hence the application is rejected Tumkur Bhavani Shankar S/o Ramchandrao R/o H.No.159 Jija Nivas Behind Sir Sai Character certificate are not enclosed. 3 3 School Edga Road Sangam Tai Hence the application is rejected Colony Kalaburagi-585103 Soheb Sameer Ali S/o Md.Shoukat Ali R/o H.No.2-907/119/192/1 Behind character certificate are not enclosed & 4 4 Inamdar Unani Medical College Age proof certificate not enclosed. Hence Chacha Layout Sedam Road the application is rejected Kalaburagi-585105 Lokesh S/o Yellappa Bhajantri R/o At Character certificate are not enclosed. 5 5 Post Belgeri Tq.Yelburga Dist.Koppal Hence the application is rejected -583232 Praveen Kumar S/o Hanamanthappa Character certificate & Age Proof R/o H.No.MD 47/2 Bheemrayana 6 6 certificate are not enclosed. Hence the Gudi Tq.Shahapur Dist: Yadgir- application is rejected 585287 Parashuram S/o Arjun Karnak R/o at Character certificate are not enclosed. -

A Conservation Action Plan for Bicknell's Thrush

A Conservation Action Plan for Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) July 2010 International Bicknell’s Thrush Conservation Group A Conservation Action Plan for Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) Editors: John Lloyd, Ecostudies Institute Scott Makepeace, Julie A. Hart New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources Christopher C. Rimmer Kent McFarland, Vermont Center for Ecostudies Randy Dettmers Mark McGarrigle, Rebecca M. Whittam New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources Emily A. McKinnon Emily A. McKinnon, York University Kent P. McFarland David Mehlman, The Nature Conservancy Members of the International Brian Mitchell, U.S. National Park Service Bicknell’s Thrush Conservation Group: Robert Ortiz Alexander, Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Santo Domingo Hubert Askanas, University of New Brunswick John Ozard, Yves Aubry, Canadian Wildlife Service / New York Department of Environmental Conservation Service Canadien de la Faune Julie Paquet, Canadian Wildlife Service / Philippe Bayard, Société Audubon Haiti Service Canadien de la Faune James Bridgland, Parks Canada / Parcs Canada Leighlan Prout, USDA Forest Service Jorge Brocca, Sociedad Ornitología de la Hispaniola Joe Racette, Frédéric Bussière, Regroupement QuébecOiseaux New York Department of Environmental Conservation Greg Campbell, Bird Studies Canada / Chris Rimmer, Vermont Center for Ecostudies Études d’Oiseaux Canada Frank Rivera, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ted Cheskey, Nature Canada Carla Sbert, Nature Canada Andrew Coughlan, Bird Studies Canada/ Judith Scarl, Vermont Center for Ecostudies Études d’Oiseaux Canada Henning Stabins, Plum Creek Timber Company William DeLuca, University of Massachusetts Jason Townsend, State University of New York College of Randy Dettmers, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Environmental Science and Forestry Antony W. Diamond, University of New Brunswick Tony Vanbuskirk, Fornebu Lumber Company Andrea Doucette, NewPage Port Hawkesbury Corp Rebecca M.