Eudynamys Scolopacea ) Inhabiting Two Different Locations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Employees Details (1).Xlsx

Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services, KALABURGI District Super Specialities ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. Namdev Rathod Assistant Director 08472-226139 9480688435 Veterinary Hospital CompoundSedam Road Kalaburagi pin Cod- 585101 Veterinary Hospitals ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. M.S. Gangnalli Assistant Director 08470-283012 9480688623 Veterinary Hospital Afzalpur Bijapur Road pin code:585301 Assistant Director 2 Dr. Sanjay Reddy (Incharge) 08477-202355 94480688556 Veterinary Hospital Aland Umarga Road pin code: 585302 3 Dr. Dhanaraj Bomma Assistant Director 08475-273066 9480688295 Veterinary Hospital Chincholi pincode: 585307 4 Dr. Basalingappa Diggi Assistant Director 08474-236226 9590709252 Veterinary Hospital opsite Railway Station Chittapur pincode: 585211 5 Dr. Raju B Deshmukh Assistant Director 08442-236048 9480688490 Veterinary Hospital Jewargi Bangalore Road Pin code: 585310 6 Dr. Maruti Nayak Assistant Director 08441-276160 9449618724 Veterinary Hospital Sedam pin code: 585222 Mobile Veterinary Clinics ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. Kimmappa Kote CVO 08470-283012 9449123571 Veterinary Hospital Afzalpur Bijapur Road pin code:585301 2 Dr. sachin CVO 08477-202355 Veterinary Hospital Aland Umarga Road pin code: 585302 3 Dr. Mallikarjun CVO 08475-273066 7022638132 Veterinary Hospital At post Chandaput Tq: chincholi pin code;585305 4 Dr. Basalingappa Diggi CVO 08474-236226 9590709252 Veterinary Hospital Chittapur 5 Dr. Subhaschandra Takkalaki CVO 08442-236048 9448636316 Veterinary Hospital Jewargi Bangalore Road Pin code: 585310 6 Dr. Ashish Mahajan CVO 08441-276160 9663402730 Veterinary Hospital Sedam pin code: 585222 Veterinary Hospitals (Hobli) ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. -

Table of Content Page No's 1-5 6 6 7 8 9 10-12 13-50 51-52 53-82 83-93

Table of Content Executive summary Page No’s i. Introduction 1-5 ii. Background 6 iii. Vision 6 iv. Objective 7 V. Strategy /approach 8 VI. Rationale/ Justification Statement 9 Chapter-I: General Information of the District 1.1 District Profile 10-12 1.2 Demography 13-50 1.3 Biomass and Livestock 51-52 1.4 Agro-Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography 53-82 1.5 Soil Profile 83-93 1.6 Soil Erosion and Runoff Status 94 1.7 Land Use Pattern 95-139 Chapter II: District Water Profile: 2.1 Area Wise, Crop Wise irrigation Status 140-150 2.2 Production and Productivity of Major Crops 151-158 2.3 Irrigation based classification: gross irrigated area, net irrigated area, area under protective 159-160 irrigation, un irrigated or totally rain fed area Chapter III: Water Availability: 3.1: Status of Water Availability 161-163 3.2: Status of Ground Water Availability 164-169 3.3: Status of Command Area 170-194 3.4: Existing Type of Irrigation 195-198 Chapter IV: Water Requirement /Demand 4.1: Domestic Water Demand 199-200 4.2: Crop Water Demand 201-210 4.3: Livestock Water Demand 211-212 4.4: Industrial Water Demand 213-215 4.5: Water Demand for Power Generation 216 4.6: Total Water Demand of the District for Various sectors 217-218 4.7: Water Budget 219-220 Chapter V: Strategic Action Plan for Irrigation in District under PMKSY 221-338 List of Tables Table 1.1: District Profile Table 1.2: Demography Table 1.3: Biomass and Live stocks Table 1.4: Agro-Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography Table 1.5: Soil Profile Table 1.7: Land Use Pattern Table -

Name of the Village

POPULATION PROFILE OF KALBURUGI Dist AS PER 2011 CENSUS Total SC ST Sl No Name of the Village % % Population Population Population 1 Gulbarga 2566326 648782 25.28 65259 2.54 2 Gulbarga 1730775 489697 28.29 50074 2.89 3 Gulbarga 835551 159085 19.04 15185 1.82 4 Aland 342207 85516 24.99 6843 2.00 5 Aland 299836 79777 26.61 6508 2.17 6 Aland 42371 5739 13.54 335 0.79 7 Jamga Khandala 1215 756 62.22 30 2.47 8 Tadola 2568 716 27.88 1 0.04 9 Alanga 2571 281 10.93 7 0.27 10 Sirur (G) 1378 240 17.42 63 4.57 11 Gadlegaon 686 250 36.44 0 0.00 12 Khajuri 6744 912 13.52 9 0.13 13 Jawalga (J) 1707 542 31.75 57 3.34 14 Tugaon 837 222 26.52 27 3.23 15 Annur 1248 295 23.64 69 5.53 16 Hodlur 2697 361 13.39 4 0.15 17 Subhashnagar 1057 1055 99.81 1 0.09 18 Nandgur 500 152 30.40 0 0.00 19 Kotanhipperga 1699 178 10.48 0 0.00 20 Jamga Ruderwadi 1766 502 28.43 0 0.00 21 Rudrawadi 3004 699 23.27 57 1.90 22 Bableshwar 884 228 25.79 65 7.35 23 Bangerga 2334 662 28.36 55 2.36 24 Khandala 1434 528 36.82 141 9.83 25 Nirgudi 3109 307 9.87 87 2.80 26 Matki 4206 732 17.40 291 6.92 27 Teerth 1636 315 19.25 12 0.73 28 Salegaon 2342 506 21.61 135 5.76 29 Chitali 1511 237 15.68 336 22.24 30 Kinnisultan 3322 745 22.43 1 0.03 31 Kanmas 1254 348 27.75 3 0.24 32 Bharked 865 97 11.21 39 4.51 33 Sangunda 1097 279 25.43 4 0.36 34 Belamogi 5127 1613 31.46 189 3.69 35 Karhari 1584 567 35.80 0 0.00 36 Salgera (V.K.) 5182 1734 33.46 137 2.64 37 Lengthi 1956 457 23.36 354 18.10 38 Ladmugli 2636 575 21.81 2 0.08 39 Kalkutga 691 184 26.63 56 8.10 40 Kudmud 1610 806 50.06 0 0.00 41 Ambalga -

1995-96 and 1996- Postel Life Insurance Scheme 2988. SHRI

Written Answers 1 .DECEMBER 12. 1996 04 Written Answers (c) if not, the reasons therefor? (b) No, Sir. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF (c) and (d). Do not arise. RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) (a) No, Sir. [Translation] (b) Does not arise. (c) Due to operational and resource constraints. Microwave Towers [Translation] 2987 SHRI THAWAR CHAND GEHLOT Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state : Construction ofBridge over River Ganga (a) the number of Microwave Towers targated to be set-up in the country during the year 1995-96 and 1996- 2990. SHRI RAMENDRA KUMAR : Will the Minister 97 for providing telephone facilities, State-wise; of RAILWAYS be pleased to state (b) the details of progress achieved upto October, (a) whether there is any proposal to construct a 1906 against above target State-wise; and bridge over river Ganges with a view to link Khagaria and Munger towns; and (c) whether the Government are facing financial crisis in achieving the said target? (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the time by which construction work is likely to be started and THE MINISTER OF COMMUNICATIONS (SHRI BENI completed? PRASAD VERMA) : (a) to (c). The information is being collected and will be laid on the Table of the House. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) : (a) No, Sir. [E nglish] (b) Does not arise. Postel Life Insurance Scheme Railway Tracks between Virar and Dahanu 2988. SHRI VIJAY KUMAR KHANDELWAL : Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: 2991. SHRI SURESH PRABHU -

Variation in Birdsong of Red Vented Bulbul ( Pycnonotus Cafer) Inhabiting Two Different Locations

Journal of Experimental Sciences 2012, 3(8): 21-25 ISSN: 2218-1768 Available Online: http://jexpsciences.com/ Variation in birdsong of red vented bulbul ( Pycnonotus cafer) Inhabiting two different locations Manjunath and Bhaskar Joshi Department of Zoology, Gulbarga University, Gulbarga, Karnataka, India Abstract This species emits a high variety of acoustic signals in their communication. The signals may be long or short and simple; these signals can be classified into songs and calls. Individuals sang throughout the year. The songs of red-vented bulbul (pycnonotus cafer ) in two regions: Gulbarga and Ainoli were studied during the period from March 2008 to June 2009. The results show that variations exist in this bird species. The songs of birds from two regions shows differences in the tone characteristics, number of syllables, duration, spectral features and frequency range of the main sentence and so on. Keywords: Pycnonotus cafer, Gulbarga, Ainoli. INTRODUCTION from which are unlikely to meet each other. Significant The vocalizations of animals are unique in that they lend macrogeographic differences between populations have been themselves readily to accurate and objective analysis, made possible demonstrated in several species, such as Lincoln’s Sparrows through the recently improved technical aids in sound recording and (Melospiza lincolnii ) (Cicero and Benowitz-Fredericks 2000), Song analysis. Birds use an array of vocal signals in their communication. sparrows ( M. melodia ) (Peters et al., 2000), Willow Flycatchers These signals may be long and complex or short and simple, and (Empidonax trailli ) (Sedgwick 2001), Golden Bowebirds ( Prionodura they may occur in particular contexts (Catchpole and Slater 1995). newtonia ) (Westcoott and Kroon 2002). -

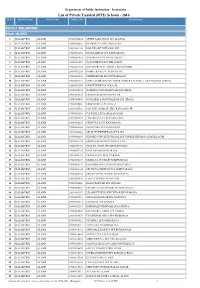

List of Private Unaided (RTE) Schools - 2016 Sl.No

Department of Public Instruction - Karnataka List of Private Unaided (RTE) Schools - 2016 Sl.No. District Name Block Name DISE Code School Name Distirct :KALABURGI Block :ALAND 1 KALABURGI ALAND 29040100204 SHREE SARASWATI LPS ALANGA 2 KALABURGI ALAND 29040100603 JNANODAYA HPS AMBALAGA 3 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101102 MALLIKARJUN HPS BOLANI 4 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101202 JNANAAMRAT LPS BANGARAGA 5 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101408 BASAWAJYOTI LPS BELAMAGI 6 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101409 NAVACHETAN LPS BELAMAGI 7 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101908 MATOSHRI NEELAMBIKA BHUSANOOR 8 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103204 INDIRA(KAN)LPS.DHANGAPUR 9 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103310 VEERESHWAR LPS DUTTARGAON 10 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103311 SHREE SIDDESHWAR LOWER PRIMARY SCHOOL LAD CHINCHOLI CROSS 11 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103505 SHANTINIKETAN GOLA (B) 12 KALABURGI ALAND 29040104105 RAMLING CHOUDESHWARI LPS HIROL 13 KALABURGI ALAND 29040104404 SIDDESHWAR HPS HODULUR 14 KALABURGI ALAND 29040105405 SUSILABAI S MANTHALKAR LPS JIDAGA 15 KALABURGI ALAND 29040105406 SIDDASHREE LPS JIDAGA 16 KALABURGI ALAND 29040105503 S.R.PATIL SMARAK HPS KADAGANCHI 17 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106203 C.B.PATIL LPS KAMALANAGAR 18 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106304 LOKAKALYAN LPS KAWALAGA 19 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106305 CHANUKYA LPS KAWAKAGA 20 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106604 NIJACHARANE HPS KHAJURI 21 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106608 SIR M VISHWESHWARAYYA LPS 22 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106609 OXFORD CONVENT SCHOOL LPS VENKTESHWAR NAGAR KHAJURI 23 KALABURGI ALAND 29040107102 SIDDESHWAR HPS KINNISULTAN 24 KALABURGI ALAND 29040107103 -

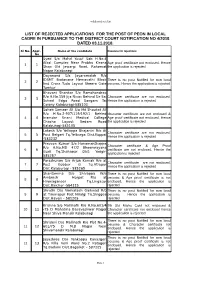

List of Rejected Applications for the Post of Peon in Local Cadre in Pursuance to the District Court Notification No 4/2018 Dated 03.11.2018

webhosted reje list LIST OF REJECTED APPLICATIONS FOR THE POST OF PEON IN LOCAL CADRE IN PURSUANCE TO THE DISTRICT COURT NOTIFICATION NO 4/2018 DATED 03.11.2018. Sl No. Appl . Name of the candidate Reasons for rejections No Syed S/o Mohd Yusuf Sab H.No.4 Afzal Complex Near Prabhu Kirana Age proof certificate not enclosed. Hence 1 1 Shop Old Jewargi Road, Rahemat the application is rejected Nagar Kalaburagi Dayanand S/o Jayaramaiah R/o IDSMT Badavane Hemavathi Block There is no post Notified for non local 2 2 Iind Cross Tuda Layout Sheera Gate persons. Hence the application is rejected Tumkur Bhavani Shankar S/o Ramchandrao R/o H.No.159 Jija Nivas Behind Sir Sai Character certificate are not enclosed. 3 3 School Edga Road Sangam Tai Hence the application is rejected Colony Kalaburagi-585103 Soheb Sameer Ali S/o Md.Shoukat Ali R/o H.No.2-907/119/192/1 Behind character certificate are not enclosed & 4 4 Inamdar Unani Medical College Age proof certificate not enclosed. Hence Chacha Layout Sedam Road the application is rejected Kalaburagi-585105 Lokesh S/o Yellappa Bhajantri R/o At Character certificate are not enclosed. 5 5 Post Belgeri Tq.Yelburga Dist.Koppal Hence the application is rejected -583232 Praveen Kumar S/o Hanamanthappa Character certificate & Age Proof R/o H.No.MD 47/2 Bheemrayana 6 6 certificate are not enclosed. Hence the Gudi Tq.Shahapur Dist: Yadgir- application is rejected 585287 Parashuram S/o Arjun Karnak R/o at Character certificate are not enclosed. -

Villagewise Mother Tongue Data Gulbarga District (Hyderabad State)

Villagewise Mother Tongue Data Gulbarga District (Hyderabad State) 315.484 1951 GUL VMT GOVERNMENT PRItSS HYDERABAD-DN. 19114 S/DAR DfsT: .. Im ',_SERAM I i CHITAPUR)" FROM ALMEL > . --,.~.,' . .. _,""" "_.".'.-. SIJAPUR DIST: RAICHUR DIST; REFERENCES R.v£R ~OAD RAILWAVS TAHSIL. }' HEAD QUARTER o DISTRIC'T } HEAD QU,ARTER @ . TAHSIL • } . 'BOUNO""Y -* -'- PREPAR£O BY THE SETTLEMENT &. LAND RECORDS O£PT. DIST. eOUNOARY---- NOTE 1. In connection with the 1951 Census, the Government of India had directed that data: pertaining only to sex and to the primary classification of the persons sexwise according to eight livelihood classes (based on the principal means of livelihood returned by the persons concerned) should be tabulated for in dividual Villages or towns. All other data, for example those relating to economic status. age, civil con dition, religion, mother-tongue, nationality, etc., were to be tabUlated only for the tracts in each district. These tracts were of two categories, namely the rural and the urban. All villages in a tah'>il, or sometirhes in more than one tahsil within the same district, constituted a rural tract, and all towns in a district, or some times in certain specific tahsils within the same district, constituted an urban tract. Thus, the 1951 Census figures pertaining to mother-tongue speakers, were made available only for the district, or for the rural or urban tracts within a district. and not for individual villages or tap-sUs. But in 1953, the Government of Hy- derabad felt that villagewise figures relating to mother-tongue speakers of the regional languages were also necessary for various administrative purposes in so far as the bi-lingual or multi-lingual areas of this State were concerned. -

ANSWERED ON:14.12.2005 TELEPHONE FACILITIES in KARNATAKA Saradgi Shri Iqbal Ahmed

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA COMMUNICATIONS AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:3255 ANSWERED ON:14.12.2005 TELEPHONE FACILITIES IN KARNATAKA Saradgi Shri Iqbal Ahmed Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY be pleased to state: (a) the present status with regard to telephone facilities and the number of villages in Karnataka where telephone facilities are yet to be provided till date; (b) whether the target fixed for the year 2004-05 has been achieved; (c) if so, the details thereof; (d) if not, the reasons therefor; (e) the number of telephone exchanges functioning in Gulbarga district and their exchange-wise capacity as on date; (f) whether the Government proposes to increase the present capacity of the existing telephone exchanges; (g) if so, the details thereof; (h) the steps taken/proposed to be taken to clear the wait-listed applicants in Gulbarga; and (i) the number of telephone exchanges converted into electronic telephone exchanges during the last three years in Gulbarga? Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATIONS AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (DR. SHAKEEL AHMAD) (a) Sir, all the 27066 villages as per Census, 1991 have already been provided with village Public telephone (VPT) facility during 2003-04 itself. Details of telephone facilities available in Karnataka are given below: - Sl. Parameter Rural No. 1 Wireline connections (Urban) 1816241 2 Wireline connections (Rural) 842068 3 Wireless in Local Loop(WLL) 38732 connections(Urban) 4 Wireless in Local Loop(WLL) 69967 connections(Rural) 5 Cellular Mobile connections 878919 6 Internet connections 55643 7 PCOs (as on 30.9.2005) 246223 8 Trunk Automatic Exchange Ckts. -

District Census Handbook, Gulbarga, Part X-A, B, Series-14

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES-14 MYSORE DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK GULBARGA DISTRICT PART X-A: TOWN AND VILLAGE DIRECTORY PART X-B: PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT P. PADMANABHA OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS MYSORB 24 12 0 24 48 72 MILE:S I I ! I M1f~(o)U ~ I ; i : i 20 0 20 40 60 10 100 kiLOMETRES ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS,I971 STATE 80UNDARY --._- DISTRICT " -.-.--- TALUK " STATE CAPITAL '* DISTRICT HEADQUARTERS (j) TALUK " o T. N....upur - TbirumaIaocUu N ....I ,. H9-Hoo.... pur MAlIARASHTRA " H_~ubU ANDHRA PRADESH TAMIL NADU JAMI MASJID, GULBARGA (Motif on the cover) THE picture illustrated on the cover page is that of Jami Masjid of Gulbarga, built by a Persian architect named Rafi in A.D. 1367, during the reign of Muhammad Shah Baihmani I (1358-1375 A.D.). The architecture of this mosque, although plain, possesses considerable fascination because of the sense of proportion and beauty of line displayed in the building. A novel feature of this mosque is that it has no open court in front of the prayer-hall, and the entire area, consisting of the aisles, the central passages and the prayer-hall is covered over on the model of the mosque of Cordova in Spain. The architect has, in this mosque, given a variety of forms to the arches by adopting different spans and using imposts of various heights. For example, the span of the arches of the aisles is extremely wide in comparison with their imposts, thus producing a new form which later became very popular in the buildings of Bijapur and Bidar. -

Gulbarga Bench

- 1 - IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA GULBARGA BENCH DATED THIS THE 3 RD DAY OF FEBRUARY 2014 BEFORE THE HON’BLE MR.JUSTICE MOHAN .M. SHANTANAGOUDAR WRIT PETITION Nos.101803-806/2013 (GM-RES) BETWEEN: 1. SUVARNA W/O NEELKANT RAO AGED ABOUT 45 YEARS OCC: HOUSEHOLD R/O BASWANAPPA BAZAR AINOLI TALUKA CHINCHOLI 2. PRAMILA D/O NEELKANT RAO AGED ABOUT 25 YEARS OCC: HOUSEHOLD R/O BASWANAPPA BAZAR AINOLI TALUKA CHINCHOLI 3. PRASHANT S/O NEELKANT RAO AGE: 20 YEARS, OCC: STUDENT R/O BASWANAPPA BAZAR AINOLI TALUKA CHINCHOLI 4. KANYA KUMARA D/O NEELKANT RAO AGE ABOUT 15 YEARS, MINOR UNDER GUARDIANSHIP OF SMT. SUVARANA W/O NEELKANT RAO, OCC: HOUSEHOLD R/O BASWANAPPA BAZAR AINOLI TALUKA CHINCHOLI ... PETITIONERS (BY SRI N.KRISHNACHARYA, ADVOCATE) - 2 - AND: 1. THE STATE OF KARNATAKA REPRESENTED BY THE EDUCATION SECRETARY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION M.S.BUILDING BANGALORE – 560 001 2. THE COMMISSIONER DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTIONS GULBARGA 3. THE DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION GULBARGA 4. THE BLOCK EDUCATION OFFICER CHINCHOLI, TALUKA CHINCHOLI DISTRICT GULBARGA 5. NEELKANT RAO S/O SHIVAPPA AGE: 50 YEARS, OCC: TEACHER GOVT. H.P.S. RAMTIRTH TALUKA CHINCHOLI DISTRICT GULBARGA ... RESPONDENTS (BY SRI MANVENDRA REDDY, GA FOR R1 TO R4) THESE WRIT PETITIONS ARE FILED UNDER ARTICLES 226 AND 227 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA PRAYING TO ISSUE WRIT OF MANDAMUS, DIRECTING THE RESPONDENTS 1 TO 4 TO RECORD THE NAMES OF THE PETITIONERS IN THE SERVICE REGISTER OF RESPONDENT NO.5 AS FAMILY MEMBERS OF THE RESPONDENT NO.5 IN PURSUANCE OF THE REPRESENTATION DATED 14.06.2013 AS PER ANNEXURE-D. -

Annexure Government of India Ministry of Science & Technology

Annexure 12011/18/2020 INSPIRE (Karnataka) Dated: 16 Dec 2020 Government of India Ministry of Science & Technology, Department of Science & Technology List of Selected Students under the INSPIRE Award Scheme for the Year 2020-21 Name of the State :Karnataka No. of Sanctioned :6879 Sr. Name of Name of Name of Sub Name of the School Name of the selected Class Sex Category Name of Father UID No Ref Code No. Revenue Education District Student or Mother District District (Block/Tehsil/Zone etc.) 1 Bagalkot BAGALKOT Badami SRI GANGA MUKAPPA 9 F SC MUKAPPA 20KA1938805 KANCHANESHWARI HADIMANI HIGH SCHOOL GULEDAGUDDA 2 Bagalkot BAGALKOT Badami SRI SANIYA MURTUZA 10 F OBC MURTUZA 20KA1938806 KANCHANESHWARI ILAKAL HIGH SCHOOL GULEDAGUDDA 3 Bagalkot BAGALKOT Badami GOVT HPS BASURAJ 7 M OBC BALAPPA 20KA1938807 HANAMASAGAR AYYANNAVAR 4 Bagalkot BADAMI(29020 Badami GHPS CHIRALKOPPA TIPPANNA 7 M OBC PADIYAPPA 20KA1938808 1) SAJJIROTTI 5 Bagalkot Bagalkot Badami KGHPS ANWAL BASAMMA 7 F OBC BHIMANAGOUDA 20KA1938809 BHIMANAGOUDA NANJAPPANAVAR 6 Bagalkot Bagalkot Badami GOVT HPS SHREEDEVI 7 F OBC BEERAPPA 20KA1938810 FAKIRBUDIHAL BEERAPPA BEERANNAVAR Page 1 of 525 Sr. Name of Name of Name of Sub Name of the School Name of the selected Class Sex Category Name of Father UID No Ref Code No. Revenue Education District Student or Mother District District (Block/Tehsil/Zone etc.) 7 Bagalkot BAGALKOT Badami GOVT HPS SHARNAPPA 7 M ST BALAPPA 20KA1938811 KOTANALLI BALAPPA GOUDAR 8 Bagalkot Bagalkot Badami sri saraswati vidya SAHANA PARAPPA 7 F OBC PARAPPA 20KA1938812