Great and Spotted Bowerbirds Chlamydera Nucha/Is and C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Variation in Bower Decorating Style Among Male Bowerbirds

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 83, pp. 3042-3046, May 1986 Population Biology Animal art: Variation in bower decorating style among male bowerbirds Amblyornis inornatus (cultural rnlsson/geographic variadon/behavior) JARED DIAMOND Physiology Department, University of California Medical School, Los Angeles, CA 90024 Contributed by Jared Diamond, December 30, 1985 ABSTRACT Courtship bowers of the bowerbird Ambly- BACKGROUND ornis inornatus, the most elaborately decorated structures Bowers are avenues, huts, or towers of sticks decorated with erected by an animal other than humans, vary geographically objects such as fruits, flowers, mushrooms, and stones. and individually. Bowers in the south Kumawa Mountains are Males often hold a decoration in their bill while displaying to tall towers of sticks glued together, resting on a circular mat of a female, and experiments confirm that bower structure and dead moss painted black, and decorated with dull objects such decorations influence females' choice of mate (7). Whereas as snall shells, acorns, and stones. Bowers in the Wandamen males are polygynous and contribute nothing to the female Mountains are low woven towers covered by a stick hut with an after copulation, females perform the whole effort ofbuilding entrance, resting on a green moss mat and decorated with a nest and rearing the young. Species comparisons show that colorful objects such as fruits, flowers, and butterfly wings. male bowerbirds with duller ornamental plumage build fan- Young males build simpler bowers, and adult males differ cier bowers (4, 8). Thus, during bowerbird evolution the among themselves. Experiments with poker chips of seven female's attention has been transferred from ornaments ofthe colors offered as decorations showed that individual birds male's body to those ofhis bower. -

Nest, Egg, Incubation Behaviour and Parental Care in the Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis Germana

Australian Field Ornithology 2019, 36, 18–23 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo36018023 Nest, egg, incubation behaviour and parental care in the Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis germana Richard H. Donaghey1, 2*, Donna J. Belder3, Tony Baylis4 and Sue Gould5 1Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Nathan 4111 QLD, Australia 280 Sawards Road, Myalla TAS 7325, Australia 3Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia 4628 Utopia Road, Brooweena QLD 4621, Australia 5269 Burraneer Road, Coomba Park NSW 2428, Australia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis germana, recently elevated to species status, is endemic to montane forests on the Huon Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. The polygynous males in the Yopno Urawa Som Conservation Area build distinctive maypole bowers. We document for the first time the nest, egg, incubation behaviour, and parental care of this species. Three of the five nests found were built in tree-fern crowns. Nest structure and the single-egg clutch were similar to those of MacGregor’s Bowerbird A. macgregoriae. Only the female Huon Bowerbird incubated. Mean length of incubation sessions was 30.9 minutes and the number of sessions daily was 18. Diurnal incubation constancy over a 12-hour day was 74%, compared with a mean of ~70% in six other members of the bowerbird family. The downy nestling resembled that of MacGregor’s Bowerbird. Vocalisations of a female Huon Bowerbird at a nest with a nestling -

Parallel Evolution of Bower-Building Behavior in Two Groups of Bowerbirds Suggested by Phylogenomics

SUPPLEMENT TO: Parallel Evolution of Bower-Building Behavior in Two Groups of Bowerbirds Suggested by Phylogenomics Per G.P. Ericson 1 *, Martin Irestedt 1, Johan A.A. Nylander 1, Les Christidis 2, Leo Joseph 3, Yanhua Qu 1, 4 * 1 Department of Bioinformatics and Genetics, Swedish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 50007, SE-104 05, Stockholm, Sweden 2 School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, Coffs Harbour, NSW, Australia, School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia 3 Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO National Research Collections Australia, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia 4 Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100101, China CONTENT 1. MATERIAL AND METHODS (DETAILED DESCRIPTION) 2. FURTHER DETAILS ABOUT SYSTEMATIC RELATIONSHIPS OBSERVED 3. DATA REPOSITORIES 4. SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES S1-S5 5. SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES S1-S2 1. MATERIAL AND METHODS (DETAILED DESCRIPTION) Taxon Sampling In the study, we include all traditionally recognized bowerbird species as well as representatives for each of the morphologically and genetically distinct populations of the genus Ailuroedus that recently were elevated from status as subspecies to full species (Irestedt et al. 2016). The number of Ailuroedus species thus increased from the traditionally recognized three species (buccoides, crassirostris and melanotis; species epithets used for brevity when possible) to ten (buccoides, stonii, geislerorum, crassirostris, maculosus, melanocephalus, astigmaticus, arfakianus, jobiensis and melanotis). We used cryo-frozen tissue samples for most taxa, but for twelve individuals DNA was extracted from toe pad samples of museum study skins (Table S1 available on Dryad). We base our information on mating system, sexual plumage dimorphism, and building of courts and bowers on Gilliard (1969), Diamond (1986a), Kusmierski et al. -

Male Courtship Vocalizations As Cues for Mate Choice in the Satin Bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus Violaceus)

MALE COURTSHIP VOCALIZATIONS AS CUES FOR MATE CHOICE IN THE SATIN BOWERBIRD (PTILONORHYNCHUS VIOLACEUS) CHRISTOPHER A. LOFFREDO AND GERALD BORGIA Departmentof Zoology,University of Maryland,College Park, Maryland 20742 USA AI3STRACT.--MaleSatin Bowerbirds(Ptilonorhynchus violaceus) court femalesat specialized structurescalled bowers. Courtship includes a complexpattern of vocalizationsin which a broad-band,mechanical-sounding song is followed by interspecificmimicry. We studiedthe effect of male courtshipdisplays on male mating successin Satin Bowerbirds.Data from 2 yearsof field researchshowed low between-maledifferences in mechanicalcomponents of courtshipsong and high variability betweenmales in mimeticsinging. Older malessang longer and higher-qualitybouts of mimicry than did youngermales. In one year, courtship song featureswere correlatedwith male mating success.The resultssuggest that female SatinBowerbirds use male courtship vocalizations in their mate-choicedecisions. We discuss hypothesesabout assessment of male age and dominancefrom courtshipvocalizations and suggestthat thesesongs have evolvedas a result of selectionfor male displaycharacteristics that provide femaleswith information about the relative quality of prospectivemates. Re- ceived27 June1985, accepted20 September1985. MALESatin Bowerbirds(Ptilonorhynchus vio- ingnessto copulateor by flying away. Given laceus)build specializedstructures called bow- the complexity of male display and the atten- ers that are used as sites for courting females tion femalespay to displayingmales, -

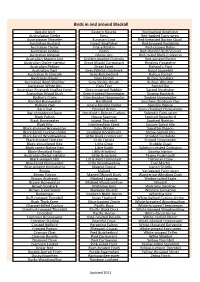

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote -

Chapter 18 Evolution of Reproductive Behavior (1St Lecture)

Chapter 18 Evolution of reproductive behavior (1st lecture) The Satin Bowerbird has an unusual courtship ritual Male constructs an female elaborate “avenue” bower, contaiing colorful objects that he has collected. When a female arrives, he performs a energetic dance while emitting a medley of male buzzes, screeches and imitations of other bird songs. The female assesses the male based on: bower attributes, the male’s dance, and location of the bower If the female decides to mate with him, then she will enter his bower, copulate, and fly away, never to see him again. She will incubate her eggs and raise young on her own. The male will continue in this manner across the 8-month breeding season, mating with as many females as possible. The design of the bower varies greatly, both among and within species Playhouse bower Different populations of Amblyornis inoratus construct different types of bower, perhaps reflecting different “aesthetic tastes” of females within each population Maypole bower Evolutionary relationships among 14 of the 19 species of bowerbird, based on similarities in their mitochondrial cytochrome b gene Note that 2 bowerbird species share the ancestral trait of not building a bower Maypole builders Presumably, the hypothetical species Y built a Avenue simple bower. builders The ensuing adaptive radiation illustrates a fantastic example of divergent evolution What are the features of the bowerbird courtship ritual that represent evolutionary conundrums? The males make absolutely no parental investment Each male mates multiple -

Standards for Ground Feeding Bird Sanctuaries

Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries Standards For Ground Feeding Bird Sanctuaries Version: June 2013 ©2012 Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries i Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries – Standards for Ground Feeding Bird Sanctuaries Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 1 GFAS PRINCIPLES 1 ANIMALS COVERED BY THESE STANDARDS 1 STANDARDS UPDATES 2 GROUND FEEDING BIRD STANDARDS 3 GROUND FEEDING BIRD HOUSING 3 H-1. Types of Space and Size 3 H-2. Containment 5 H-3. Ground and Plantings 6 H-4. Gates and Doors 7 H-5. Shelter 8 H-6. Enclosure Furniture 8 H-7. Sanitation 9 H-8. Temperature, Humidity, Ventilation, Lighting 11 PHYSICAL FACILITIES AND ADMINISTRATION 12 PF-1. Overall Safety of Facilities 12 PF-2. Water Drainage and Testing 13 PF-3. Life Support 13 PF-4. Hazardous Materials Handling 13 PF-5. Security: Avian Enclosures 14 PF-6. Perimeter Boundary and Inspections, and Maintenance 14 PF-7. Security: General Safety Monitoring 15 PF-8. Insect and Rodent Control 15 PF-9. Record Keeping 16 PF-10. Animal Transport 16 NUTRITION REQUIREMENTS 18 N-1. Water 18 N-2. Diet 18 N-3. Food Presentation and Feeding Techniques 20 N-4. Food Storage 21 N-5. Food Handling 21 VETERINARY CARE 22 V-1. General Medical Program and Staffing 22 V-2. On-Site and Off-Site Veterinary Facilities 22 V-3. Preventative Medicine Program 23 V-4. Diagnostic Services, Surgical, Treatment and Necropsy Facilities 23 V-5. Quarantine and Isolation of Ground Feeding Birds 25 V-6. Medical Records and Controlled Substances 26 i Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries – Standards for Ground Feeding Bird Sanctuaries V-7. -

Indicus Biological Consultants

Indicus Biological Consultants Darwin City Waterfront (Darwin Wharf) Redevelopment Terrestrial fauna assessment December 2003 James Smith Ronald Firth This document is and shall remain the property of Indicus Biological Consultants. The document may only be used for the purposes for which it was commissioned and in accordance with the Terms of the Engagement for the commission. Unauthorised use of this document in any form whatsoever is prohibited. 29 Aralia Street, Nightcliff phone: (08) 8411 0350 email: [email protected] Contents www.indicusbc.netfirms.com Terrestrial Fauna Assessment Darwin City Waterfront Redevelopment December 2003 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................................................................3 SURVEY METHODS ................................................................................................................................................................3 Bird counts ........................................................................................................................................................................3 Active Searches .................................................................................................................................................................3 Incidental records ..............................................................................................................................................................4 Bat -

Teaching & Researching Big History: Exploring a New Scholarly Field

Teaching & Researching Big History: Exploring a New Scholarly Field Leonid Grinin, David Baker, Esther Quaedackers, Andrey Korotayev To cite this version: Leonid Grinin, David Baker, Esther Quaedackers, Andrey Korotayev. Teaching & Researching Big History: Exploring a New Scholarly Field. France. Uchitel, pp.368, 2014, 978-5-7057-4027-7. hprints- 01861224 HAL Id: hprints-01861224 https://hal-hprints.archives-ouvertes.fr/hprints-01861224 Submitted on 24 Aug 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain INTERNATIONAL BIG HISTORY ASSOCIATION RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES The Eurasian Center for Big History and System Forecasting TEACHING & RESEARCHING BIG HISTORY: EXPLORING A NEW SCHOLARLY FIELD Edited by Leonid Grinin, David Baker, Esther Quaedackers, and Andrey Korotayev ‘Uchitel’ Publishing House Volgograd ББК 28.02 87.21 Editorial Council: Cynthia Stokes Brown Ji-Hyung Cho David Christian Barry Rodrigue Teaching & Researching Big History: Exploring a New Scholarly Field / Edited by Leonid E. Grinin, David Baker, Esther Quaedackers, and Andrey V. Korotayev. – Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’ Publishing House, 2014. – 368 pp. According to the working definition of the International Big History Association, ‘Big History seeks to understand the integrated history of the Cosmos, Earth, Life and Humanity, using the best available empirical evidence and scholarly methods’. -

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA updates. for Edition 4th Editors See A.C. Robinson K.D. Casperson Biological Survey and Research Heritage and Biodiversity Division Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia M.N. Hutchinson South Australian Museum Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts, South Australia 2000 i EDITORS A.C. Robinson & K.D. Casperson, Biological Survey and Research, Biological Survey and Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage. G.P.O. Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001 M.N. Hutchinson, Curator of Reptiles and Amphibians South Australian Museum, Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts. GPO Box 234, Adelaide, SA 5001updates. for CARTOGRAPHY AND DESIGN Biological Survey & Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage Edition Department for Environment and Heritage 2000 4thISBN 0 7308 5890 1 First Edition (edited by H.J. Aslin) published 1985 Second Edition (edited by C.H.S. Watts) published 1990 Third Edition (edited bySee A.C. Robinson, M.N. Hutchinson, and K.D. Casperson) published 2000 Cover Photograph: Clockwise:- Western Pygmy Possum, Cercartetus concinnus (Photo A. Robinson), Smooth Knob-tailed Gecko, Nephrurus levis (Photo A. Robinson), Painted Frog, Neobatrachus pictus (Photo A. Robinson), Desert Goby, Chlamydogobius eremius (Photo N. Armstrong),Osprey, Pandion haliaetus (Photo A. Robinson) ii _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS -

Managing Bird Damage

Managing Bird Damage Managing Bird Managing Bird Damage Bird damage is a significant problem in Australia with total to Fruit and Other Horticultural Crops damage to horticultural production estimated at nearly $300 million annually. Over 60 bird species are known to damage horticultural crops. These species possess marked differences in feeding strategies and movement patterns which influence the nature, timing and severity of the damage they cause. Reducing bird damage is difficult because of the to Fruit and Other Horticultural Crops Fruit and Other Horticultural to unpredictability of damage from year to year and a lack of information about the cost-effectiveness of commonly used management practices. Growers therefore need information on how to better predict patterns of bird movement and abundance, and simple techniques to estimate the extent of damage to guide future management investment. This book promotes the adoption of a more strategic approach to bird management including use of better techniques to reduce damage and increased cooperation between neighbours. Improved collaboration and commit- John Tracey ment from industry and government is also essential along with reconciliation of legislation and responsibilities. Mary Bomford Whilst the focus of this review is pest bird impacts on Quentin Hart horticulture, most of the issues are of relevance to pest bird Glen Saunders management in general. Ron Sinclair DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, FISHERIES AND FORESTRY Managing Bird Damage Managing Bird Managing Bird Damage Bird damage is a significant problem in Australia with total to Fruit and Other Horticultural Crops damage to horticultural production estimated at nearly $300 million annually. Over 60 bird species are known to damage horticultural crops. -

Birds of New Guinea Field Guide (Beehler Et Al

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The New Guinea Region Our region of coverage follows Mayr (1941: vi), who defined the natural region that encompasses the avifauna of New Guinea, naming it the “New Guinea Region.” It comprises the great tropical island of New Guinea as well as an array of islands lying on its continental shelf or immediately offshore. This region extends from the equator to latitude 12o south and from longitude 129o east to 155o east; it is 2,800 km long by 750 km wide and supports the largest remaining contiguous tract of old-growth humid tropical forest in the Asia-Pacific (Beehler 1993a). The Region includes the Northwestern Islands (Raja Ampat group) of the far west—Waigeo, Batanta, Salawati, Misool, Kofiau, Gam, Gebe, and Gag; the Aru Islands of the southwest—Wokam, Kobroor, Trangan, and others; the Bay Islands of Geelvink/Cenderawasih Bay—Biak-Supiori, Numfor, Mios Num, and Yapen; Dolak Island of south-central New Guinea (also known as Dolok, Kimaam, Kolepom, Yos Sudarso, or Frederik Hendrik); Daru and Kiwai Islands of eastern south-central New Guinea; islands of the north coast of Papua New Guinea (PNG)—Kairiru, Muschu, Manam, Bagabag, and Karkar; and the Southeastern (Milne Bay) Islands of the far southeast—Goodenough, Fergusson, Normanby, Kiriwina, Kaileuna, Wood- lark, Misima, Tagula/Sudest, and Rossel, plus many groups of smaller islands (see the endpapers for a graphic delimitation of the Region).