Making Connections: Municipal Governance Priorities Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 26, 2007 the Free-Content News Source That You Can Write! Page 1

January 26, 2007 The free-content news source that you can write! Page 1 Top Stories Wikipedia Current Events "Once a year we go to Austria to hunt with our dogs, and at the end Two major political parties • A curfew is imposed in Beirut of the day we sit on the verandah protest placards used in after deadly clashes erupted and drink a beer. So we thought, Armenan-Turkish journalist's between pro government my dog also has earned it," said funeral supporters and Hezbollah-led Berenden. Thousands of people marched in factions. Dink's Funeral to protest his •Ecuador's Defense Minister According to Berenden, owners can assassination, holding Guadalupe Larriva is killed along enjoy the new beer as well, but she placards that read with three pilots and her daughter also stated that it will cost owners "We are all Armenian" in a crash involving two about four times as much to drink and "We are Hrant helicopters. Larriva was the first the beer than to buy a 'human Dink" in both Turkish, woman to serve as the country's beer.' A bottle of the dog beer sells Kurdish and defense minister. at about $2.14. Armenian. Later, these placards were protested by MHP and CHP. •276 people onboard the Cunard The slogan for the new dog beer is The leader of MHP, a fascist Line's RMS Queen Elizabeth 2 are "a beer for your best friend" and political party of Turkey, described sickened by the norovirus during Brenden hopes that the product will the placards saying "We are all its 2007 circumnavigation of the grab international attention. -

Ontario Members of Provincial Parliament

Ontario Members of Provincial Parliament Government Office Constituency Office Government Office Constituency Office Sophia Aggelonitis, Parliamentary Assistant to the Laura Albanese, Parliamentary Assistant to the Minister of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Minister of Culture Hamilton Mountain, Liberal York South-Weston, Liberal Ministry of Small Business and Unit 2 - 952 Concession St Ministry of Culture Unit 102 - 2301 Keele St Entrepreneurship Hamilton ON L8V 1G2 900 Bay Street, 4th Floor, Toronto ON M6M 3Z9 1309 - 99 Wellesley St W, 1st Tel : 905-388-9734 Mowat Block Tel : 416-243-7984 Flr, Whitney Block Fax : 905-388-7862 Toronto ON M7A 1L2 Fax : 416-243-0327 Toronto ON M7A 1W2 saggelonitis.mpp.co Tel : 416-325-1800 [email protected] Tel : 416-314-7882 @liberal.ola.org Fax : 416-325-1802 Fax : 416-314-7906 [email protected] [email protected] Ted Arnott Wayne Arthurs, Parliamentary Assistant to the Wellington-Halton Hills, Progressive Conservative Minister of Finance Rm 420, Main Legislative 181 St. Andrew St E, 2nd Flr Pickering-Scarborough East, Liberal Building Fergus ON N1M 1P9 Ministry of Finance 13 - 300 Kingston Rd Toronto ON M7A 1A8 Tel : 519-787-5247 7 Queen's Park Cres, 7th Flr, Pickering ON L1V 6Z9 Tel : 416-325-3880 Fax : 519-787-5249 Frost Bldg South Tel : 905-509-0336 Fax : 416-325-6649 Toll Free : 1-800-265-2366 Toronto ON M7A 1Y7 Fax : 905-509-0334 [email protected] [email protected] Tel : 416-325-3581 Toll-Free: 1-800-669-4788 Fax : 416-325-3453 [email protected] -

September 26Th, 2006

Town of Milton 150 Mary Street Milton, Ontario L9T 6Z5 Phone 905-878-7252 Fax 905-878-6995 www.milton.ca May 26, 2009 Regional Municipality of Halton 1151 Bronte Road Oakville, ON L6M 3L1 ATT: Mark Meneray VIA: Email – [email protected] Dear Mr. Meneray, RE: Staff Report PD-052-09 - Sustainable Halton – Progress Report and Update Please be advised that the Administration and Planning Standing Committee, at their meeting held on May 19, 2009, considered the aforementioned topic and the following recommendation was made and ratified by Milton Council at their meeting held on May 25, 2009: THAT the Town Clerk be directed to inform the Region of Halton that Milton Council endorses Halton Region’s proposed ROPA No. 37, subject to the modifications provided by local staff (attached as Appendix A to Report No. PD-052-09), specifically noting that the additional policies are designed to accommodate the Milton Education Village and additional employment lands without further amendment to the Region of Halton Official Plan; AND THAT the Town Clerk be directed to inform the Region of Halton that Milton Council endorses Sustainable Halton Concept #2 as the Preferred Concept, whereby an additional 20,000 population/people and approximately 5000 intensification units are directed to Halton Hills (Georgetown), subject to: i) the proposed modifications to ROPA No. 37, as recommended through Report No. PD-052-09, being accepted by the Region; ii) Concept #2 meeting Milton’s First Principles of Growth, which were unanimously approved by Milton Council -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 86 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ......................................96 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.........................................94 Total number of seats ................79 Surrey-Panorama Ridge..........................Jagrup Brar..........................................95 Liberal..........................................46 Surrey-Tynehead.....................................Dave S. Hayer.....................................96 New Democratic Party ...............33 Surrey-Whalley.......................................Bruce Ralston......................................98 Abbotsford-Clayburn..............................John van Dongen ................................99 Surrey-White Rock .................................Gordon Hogg ......................................96 Abbotsford-Mount Lehman....................Michael de Jong..................................96 Vancouver-Burrard.................................Lorne Mayencourt ..............................98 Alberni-Qualicum...................................Scott Fraser .........................................96 Vancouver-Fairview ...............................Gregor Robertson................................98 Bulkley Valley-Stikine ...........................Dennis -

Ontario Gazette Volume 140 Issue 43, La Gazette De L'ontario Volume 140

Vol. 140-43 Toronto ISSN 0030-2937 Saturday, 27 October 2007 Le samedi 27 octobre 2007 Proclamation ELIZABETH THE SECOND, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom, ELIZABETH DEUX, par la grâce de Dieu, Reine du Royaume-Uni, du Canada and Her other Realms and Territories, Queen, Head of the Canada et de ses autres royaumes et territoires, Chef du Commonwealth, Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. Défenseur de la Foi. Family Day, the third Monday of February of every year, is declared a Le jour de la Famille, troisième lundi du mois de février de chaque année, holiday, pursuant to the Retail Business Holidays Act, R.S.O. 1990, est déclaré jour férié conformément à la Loi sur les jours fériés dans le Chapter R.30 and of the Legislation Act, 2006, S.O. 2006 c. 21 Sched. F. commerce de détail, L.R.O. 1990, chap. R.30, et à la Loi de 2006 sur la législation, L.O. 2006, chap. 21, ann. F. WITNESS: TÉMOIN: THE HONOURABLE L’HONORABLE DAVID C. ONLEY DAVID C. ONLEY LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR OF OUR LIEUTENANT-GOUVERNEUR DE NOTRE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO PROVINCE DE L’ONTARIO GIVEN at Toronto, Ontario, on October 12, 2007. FAIT à Toronto (Ontario) le 12 octobre 2007. BY COMMAND PAR ORDRE DAVID CAPLAN DAVID CAPLAN Minister of Government Services (140-G576) ministre des Services gouvernementaux Parliamentary Notice Avis parlementaire RETURN OF MEMBER ÉLECTIONS DES DÉPUTÉS Notice is Hereby Given of the receipt of the return of members on Nous accusons réception par la présente des résultats du scrutin, or after the twenty-sixth day of October, 2007, to represent -

Recognizing the Economic Contribution of the Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector

Community Dispatch An InfoFax of Community Development Halton January 2006 Vol. 10, No. 1 RECOGNIZING THE ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION OF THE NONPROFIT AND VOLUNTARY SECTOR Community Development Halton (CDH) has work settings employing less than 10 people. launched a study of the nonprofit human services This proportion of employees in smaller sector in Halton that will focus on the economic workplaces is almost equivalent to the contribution of the sector to the community proportion of employment for small business through its human resources, both paid employees workplaces in the private sector. and volunteers. The study is funded by Service Canada. It informs the work of Regional Chairman Joyce Savoline’s Roundtable on the Hall and MacPherson in their study, A Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector in Halton that has Provincial Portrait of Canada’s Charities, been convened to address issues related to the estimate that the annual payroll expenditures diminishing infrastructure faced by nonprofit of the nonprofit sector, excluding hospitals, organizations. universities and colleges, is more than $20 billion and that the total value of assets in the This is the first of a series of Community voluntary sector is between $44 and $78 Dispatches on the nonprofit and voluntary sector billion. The economic scale of the sector is in Halton. It will focus on the economic role of beginning to be appreciated from these first the sector and is based on national survey research explorations. research and a presentation made by Peter Clutterbuck of the Social Planning Network of Ontario at the “Funding Matters Workshop” In recent years, Statistics Canada is measuring organized by CDH in November 2003. -

2003 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2003 SPECIAL BULLETIN NO. 55 SEPTEMBER 2004 COMMUNIQUÉ NO. 55 SEPTEMBRE 2004 CHAIR OF THE BOARD AND PRESIDENT AND CEO’S REPORT Marnie Spears and Roger Wheelock Royal Botanical Gardens’ mix of natural lands, display gardens, interpreted collections, and rare and endangered plant and animal species spread over 1,100 hectares makes it a highly complex organization. We are classified as a botanical garden, a nature reserve, a farm, a cultural agency, a charity, a museum, an educational institution, and a scientific organization to name just a few of our labels. Our mandate is legislated by the province of Ontario and is as broad as the diversity of our lands. It states that we are to be responsible stewards of our gardens, collections and natural lands, and to generate knowledge for the benefit of future generations. However, while adhering to our mandate, we must pay attention to cash flow, which, for us is as essential as breathing. Unanticipated challenges don’t foundation for an expanded special events program. And, help the bottom line. In 2003 we felt the impact of SARS, RBG Centre will transform into the enterprises “hub” of West Nile virus, and difficult Canada/US border relations, The Gardens with a convention and conference centre, creating a substantial negative impact on our revenues. improved retail and food services, a science and education centre, and The Gardens’ administration. The Gardens depends on revenues from admissions, facility rental fees, retail, food and beverage, trail donations, Over the next few years, visitors will begin to see a shift to a program registrations and other services. -

Celebrating Our 50Th Anniversary

our hospital.our future. Celebrating our 50th Anniversary JOSEPH JOSEPHBRANT BRANT MEMORIAL HOSPITAL MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 1961-2011 annual report 2010/11 report annual celebrating 50 years A message from the Board of Governors Chair and President and CEO Susan Busby, Chair Eric Vandewall Board of Governors President and CEO As we mark our 50th anniversary, we pause to reflect on the remarkable successes of our hospital team and look forward to our redevelopment and expansion. 2 This year’s remarkable successes added year, our Accreditation survey was a tremendous along with our quality indicators. Strengthening momentum to Joseph Brant Memorial Hospital’s success, and much more important, a great learning quality and patient safety is a topic at the front of transformation, as we prepare for our largest experience for all staff. We recently received our every leadership, Board and team meeting – and expansion ever – an expansion that will position Accreditation certificate from Accreditation Canada it remains a focal point for all our activities – after the hospital to successfully meet the health care and it will be proudly displayed in our hospital. all, our patients are at the the centre of everything needs of Burlington and area residents for many Thanks to the efforts of our entire hospital team, we do. years to come. we are proud of our balanced budget position, Our successful Accreditation and our positive As we mark our 50th anniversary, our community something we have been able to achieve for a results on internal and required public reporting hospital has expanded on quality and safety second consecutive year and with no reduction are indicators that our efforts are yielding positive initiatives, continued to focus on evidence in patient care services. -

Georgetown Acton

5 Carr to run for Region chair Install * January 1, 2010 Friday, Press, Independent & Free By TIM FORAN mer chair Joyce Savoline. But that doesn’t Metroland Media Group mean Carr and his team have been tight- Today! LAST 21 DAYS ! wads. In fact, it’s the opposite. Halton regional chair and former mi- The Region’s overall budget has jumped REPLACE YOUR OLD FURNACE WITH A nor pro hockey player Gary Carr passed to $1.1 billion in 2010 from $759 million on something last week he was told by in 2006, with the municipality buoyed by HIGH EFFICIENCY GAS FURNACE George Armstrong in 1975, when Carr was more property tax dollars coming in from a teenage goalie being coached by the for- the industries, businesses and residents lo- WITH ENERGY SAVING MOTOR FOR mer Maple Leaf captain on the Memorial cating in Halton over the past few years. $ Cup-winning Marlboros. However, the percentage of the budget AS LOW AS 1,243 (AFTER REBATE) GST INCLUDED* “He said, ‘You’re only as good as your coming from property taxes and money OR last game’,” recalled Carr. paid by residents and businesses *HRTC Carr is now hoping his last on water bills has dropped to 42 REPLACE YOUR OLD FURNACE AND game, last Wednesday’s council per cent from 50 per cent over Up To $1350 session, during which he and the the same time period. AIR CONDITIONER FOR Rebate council he leads approved a 2010 So who’s picking up the slack, $ Ends Soon! budget with a tax and water rate if not local taxpayers? The two AS LOW AS 3,418 (AFTER REBATE) freeze, as well as an update to the groups Carr has harangued for municipality’s Offi cial Plan, is money since arriving at region- GST INCLUDED* good enough to take to the cam- al headquarters— developers • DON’T PAY TILL 2010 * paign trail next year. -

New Directions” and Help Make Our Dream a Reality

NewJoseph BrantDirections Museum Fundraising Campaign A New Concept. A New Experience. Dear Thank you for taking your valuable time to review our Joseph Brant Museum Expansion and Renovation fundraising Campaign Presentation. For nearly 30 years, the need to improve the Museum facility has been recognized and well documented, but it always seemed to be that the timing was not right. Today, we believe that our dream can become a reality with the transformation of Joseph Brant Museum into Burlington’s Community Museum & Heritage Centre to create a new concept and a new experience. We have an approved strategic plan and budget from the City of Burlington Council and staff; we have letters of support from all levels of government including Mayor Rick Goldring, Mike Wallace MP and Jane McKenna MPP, as well as endorsements from Tourism Burlington, Burlington Art Centre, heritage organizations and local business entrepreneurs. As a respected community-minded benefactor, we trust that you will see the huge cultural, educational and financial benefits that this expansion can bring to the citizens of Burlington. On behalf of the Burlington Museums Foundation, I invite you to consider becoming a generous leadership donor to the Campaign for the Renovation and Expansion of Joseph Brant Museum. Thank you. John Doyle Barbara Teatero Foundation Chair, Director of Museums, Museums of Burlington Museums of Burlington OurOur VisionVision Just Imagine Just imagine; the first blockbuster exhibition has finally opened at the newly renovated and dramatically -

Core 1..164 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 7.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 011 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, October 19, 2004 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 521 HOUSE OF COMMONS Tuesday, October 19, 2004 The House met at 10 a.m. second report is on the meeting of the Cooperation and Development Committee, held from May 24 to 27, 2004, in Marrakesh, Morocco. Prayers *** Ï (1005) ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS [English] Ï (1000) [English] PETITIONS COMMISSIONER OF OFFICIAL LANGUAGES CONSTITUTION ACT The Speaker: I have the honour, pursuant to section 66 of the Official Languages Act, to lay upon the table the annual report of the Mrs. Cheryl Gallant (Renfrew—Nipissing—Pembroke, CPC): Commissioner of Official Languages covering the period from April Mr. Speaker, today I present a petition in which the petitioners state 1, 2003 to March 31, 2004. that the federal government has abandoned rural communities under the weight of urban socialism and government regulations, and that since the Government of Canada has enforced gun control, animal [Translation] control, unnecessary pollution or waste control for farmland, bush Pursuant to Standing Order 108(3)(f), this report is deemed to and forest control, only by amending the Canadian Constitution to have been permanently referred to the Standing Committee on include property rights will the legal means exist to protect and Official Languages. defend individuals from government interference and injustice and solve the democratic deficit that has been created by the federal *** government. -

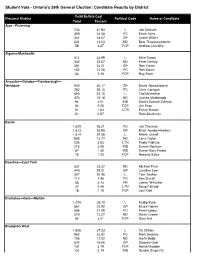

Candidate Results W Late Results

Student Vote - Ontario's 39th General Election: Candidate Results by District Valid Ballots Cast Electoral District Political Code Name of Candidate Total Percent Ajax—Pickering 743 41.93 L Joe Dickson 409 23.08 PC Kevin Ashe 331 18.67 GP Cecile Willert 231 13.03 ND Bala Thavarajasoorier 58 3.27 FCP Andrew Carvalho Algoma-Manitoulin 514 33.99 L Mike Brown 432 28.57 ND Peter Denley 351 23.21 GP Ron Yurick 152 10.05 PC Ron Swain 63 4.16 FCP Ray Scott Ancaster—Dundas—Flamborough— Westdale 940 30.17 GP David Januczkowski 782 25.10 PC Chris Corrigan 690 22.15 L Ted Mcmeekin 473 15.18 ND Juanita Maldonado 94 3.01 IND Martin Samuel Zuliniak 64 2.05 FCP Jim Enos 51 1.63 COR Eileen Butson 21 0.67 Sam Zaslavsky Barrie 1,629 26.21 PC Joe Tascona 1,613 25.95 GP Erich Jacoby-Hawkins 1,514 24.36 L Aileen Carroll 856 13.77 ND Larry Taylor 226 3.63 LTN Paolo Fabrizio 215 3.45 IND Darren Roskam 87 1.39 IND Daniel Gary Predie 75 1.20 FCP Roberto Sales Beaches—East York 531 35.37 ND Michael Prue 440 29.31 GP Caroline Law 307 20.45 L Tom Teahen 112 7.46 PC Don Duvall 56 3.73 FR James Whitaker 37 2.46 LTN Doug Patfield 18 1.19 FCP Joel Kidd Bramalea—Gore—Malton 1,079 38.70 L Kuldip Kular 667 23.92 GP Bruce Haines 588 21.09 PC Pam Hundal 370 13.27 ND Glenn Crowe 84 3.01 FCP Gary Nail Brampton West 1,526 37.23 L Vic Dhillon 962 23.47 PC Mark Beckles 706 17.22 ND Garth Bobb 642 15.66 GP Sanjeev Goel 131 3.19 FCP Norah Madden 131 3.19 IND Gurdial Singh Fiji Brampton—Springdale 1,057 33.95 ND Mani Singh 983 31.57 L Linda Jeffrey 497 15.96 PC Carman Mcclelland