RV Jones on the Intelligence War and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Stalin Revolutionary, Politician, Generalissimus and Dictator

Military Despatches Vol 34 April 2020 Flip-flop Generals that switch sides Surviving the Arctic convoys 93 year WWII veteran tells his story Joseph Stalin Revolutionary, politician, Generalissimus and dictator Aarthus Air Raid RAF Mosquitos destory Gestapo headquarters For the military enthusiast CONTENTS April 2020 Page 14 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and techno-speak that few Russian Special Forces outside the military could hope to under- stand. Some of the terms Features 34 were humorous, some A matter of survival were clever, while others 6 This month we continue with were downright crude. Ten generals that switched sides our look at fish and fishing for Imagine you’re a soldier heading survival. into battle under the leadership of Part of Hipe’s “On the a general who, until very recently 30 couch” series, this is an been trying very hard to kill you. interview with one of How much faith and trust would Ranks you have in a leader like that? This month we look at the author Herman Charles Army of the Republic of Viet- Bosman’s most famous 20 nam (ARVN), the South Viet- characters, Oom Schalk Social media - Soldier’s menace namese army. A taxi driver was shot Lourens. Hipe spent time in These days nearly everyone has dead in an ongoing Hanover Park, an area a smart phone, laptop or PC plagued with gang with access to the Internet and Quiz war between rival taxi to social media. -

Reginald Victor Jones CH FRS (1911-1997)

Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Reginald Victor Jones CH FRS (1911-1997) by Alan Hayward NCUACS catalogue no. 95/8/00 R.V. Jones 1 NCUACS 95/8/00 Title: Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Reginald Victor Jones CH FRS (1911-1997), physicist Compiled by: Alan Hayward Description level: Fonds Date of material: 1928-1998 Extent of material: 230 boxes, ca 5000 items Deposited in: Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge CB3 0DS Reference code: GB 0014 2000 National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists, University of Bath. NCUACS catalogue no. 95/8/00 R.V. Jones 2 NCUACS 95/8/00 The work of the National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists, and the production of this catalogue, are made possible by the support of the Research Support Libraries Programme. R.V. Jones 3 NCUACS 95/8/00 NOT ALL THE MATERIAL IN THIS COLLECTION MAY YET BE AVAILABLE FOR CONSULTATION. ENQUIRIES SHOULD BE ADDRESSED IN THE FIRST INSTANCE TO: THE KEEPER OF THE ARCHIVES CHURCHILL ARCHIVES CENTRE CHURCHILL COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE R.V. Jones 4 NCUACS 95/8/00 LIST OF CONTENTS Items Page GENERAL INTRODUCTION 6 SECTION A BIOGRAPHICAL A.1 - A.302 12 SECTION B SECOND WORLD WAR B.1 - B.613 36 SECTION C UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN C.1 - C.282 95 SECTION D RESEARCH TOPICS AND SCIENCE INTERESTS D.1 - D.456 127 SECTION E DEFENCE AND INTELLIGENCE E.1 - E.256 180 SECTION F SCIENCE-RELATED INTERESTS F.1 - F.275 203 SECTION G VISITS AND CONFERENCES G.1 - G.448 238 SECTION H SOCIETIES AND ORGANISATIONS H.1 - H.922 284 SECTION J PUBLICATIONS J.1 - J.824 383 SECTION K LECTURES, SPEECHES AND BROADCASTS K.1 - K.495 450 SECTION L CORRESPONDENCE L.1 - L.140 495 R.V. -

Lord Healey CH MBE PC

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 31 (Incorporating the Proceedings of the Bomber Command Association’s 60th Anniversary Symposium) 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Photographs credited to MAP have been reproduced by kind permission of Military Aircraft Photographs. Copies of these, and of many others, may be obtained via http://www.mar.co.uk First published in the UK in 2004 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR 4 DEFENCE – The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC HOW DECISIVE WAS THE ROLE OF ALLIED AIR POWER 17 IN THE WAR IN THE PACIFIC, 1941-1945? by Sqn Ldr S I Richards SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SEVENTEENTH 47 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 10 JUNE 2003 FEEDBACK 51 DEREK WOOD – AN OBITUARY 55 BOOK REVIEWS 56 PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOMBER COMMAND 82 ASSOCIATION 60TH ANNIVERSARY SYMPOSIUM HELD AT THE RAF MUSEUM, HENDON ON 12 OCTOBER 2002 UNDER THE CHAIRMANSHIP OF AIR MSHL SIR JOHN CURTISS KCB KBE 4 RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC I should perhaps start by saying that there is no specific theme to what I have to say. -

The Magazine of RAF 100 Group Association

. The magazine of RAF 100 Group Association RAF 100 Group Association Chairman Roger Dobson: Tel: 01407 710384 RAF 100 Group Association Secretary Janine Bradley: Tel: 01723 512544 Email: [email protected] www.raf100groupassociation.org.uk Home to RAF 100 Group Association Memorabilia City of Norwich Aviation Museum Old Norwich Road, Horsham St Faith, Norwich, Norfolk NR10 3JF Telephone: 01603 893080 www.cnam.org.uk 2 Dearest Friends My heartfelt thanks to the kind and generous member who sent a gorgeous bouquet of flowers on one of my darkest days. Thank you so much! The card with them simply said: ‘ RAF 100 Group’ , and with the wealth of letters and cards which continue to arrive since the last magazine, I feel your love reaching across the miles. Thank you everyone for your support and encouragement during this difficult time. It has now passed the three month marker since reading that shocking email sent by Tony telling me he wasn’t coming home from London … ever ! I now know he has been leading a double life, and his relationship with another stretches back into the past. I have no idea what is truth and what is lies any more. To make it worse, they met up here in the north! There are times when I feel my heart can’t take any more … yet somehow, something happens to tell me I am still needed. My world has shrunk since I don’t have a car any more. Travel is restricted. But right here in Filey I now attend a Monday Lunch Club for my one hot meal of the week. -

Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence

Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence Jon Woronoff, Series Editor 1. British Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2005. 2. United States Intelligence, by Michael A. Turner, 2006. 3. Israeli Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana, 2006. 4. International Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2006. 5. Russian and Soviet Intelligence, by Robert W. Pringle, 2006. 6. Cold War Counterintelligence, by Nigel West, 2007. 7. World War II Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2008. 8. Sexspionage, by Nigel West, 2009. 9. Air Intelligence, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2009. Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 9 The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road Plymouth PL6 7PY United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Trenear-Harvey, Glenmore S., 1940– Historical dictionary of air intelligence / Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey. p. cm. — (Historical dictionaries of intelligence and counterintelligence ; no. 9) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-5982-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8108-5982-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-6294-4 (eBook) ISBN-10: 0-8108-6294-8 (eBook) 1. -

Coventry: Thursday, 14 November 1940 Ebook, Epub

COVENTRY: THURSDAY, 14 NOVEMBER 1940 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Frederick Taylor | 368 pages | 10 Jan 2017 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408860281 | English | London, United Kingdom Coventry: Thursday, 14 November 1940 PDF Book Coventry Cathedral was left as a ruin, and is today still the principal reminder of the bombing. Historian Dr Henry Irving, an associate fellow at the Institute of English Studies, said: "What Harrisson describes is a psychological desperation and helplessness. Spence later knighted for this work insisted that instead of re-building the old cathedral it should be kept in ruins as a garden of remembrance and that the new cathedral should be built alongside, the two buildings together effectively forming one church. Retrieved 15 October He said: "The houses on both sides of the street were burning. Accessibility help Skip to navigation Skip to content Skip to footer. They state that while Churchill was indeed aware that a major bombing raid would take place, no one knew what the target would be. Preview — Coventry by Frederick Taylor. Teaching the Bible through popular culture and the arts. Aug 08, Luke Ryan rated it really liked it. The target was Coventry, a manufacturing city in the heart of England with a beautiful medieval centre. Given the intensity of the raid, casualties were limited by the fact that a large number of Coventrians "trekked" out of the city at night to sleep in nearby towns or villages following the earlier air raids. It also provided the push America needed to join Britain in the war. Scientist Reginald Victor Jones , who led the British side in the Battle of the Beams , wrote that "Enigma signals to the X-beam stations were not broken in time" and that he was unaware that Coventry was the intended target. -

Subject Reference Dbase 09-05-2006

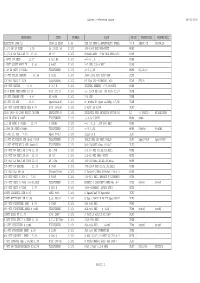

Subject reference dbase 09-05-2006 ONDERWERP TYPE NUMMER BIJZ GROEP TREFWOORD1 TREFWOORD2 ELECTRON 1958.12 1958.12 ELEC Z 46 TEK CX GEVR L,KWANTONETC KUBEL TS-N KERST CX LW,KW,LO 0,5/1 KW LW SEND 2.39 As 33/A1 34 Z 101 100-1000 KHZ MOB+FEST MOBS 0,7/1,4 KW SEND AS 60 10.40 AS 60 Z 101 FRUEHE AUSF 3-24 MHZ MOB+FEST MOBS 1 KWTT KW SEND 11.37 S 521 Bs Z 101 =+/-G 1,5.... MOBS 1 KWTT SHORT WAVE TR 5.36 S 486F Z 101 3-7 UND 2,5-6 MHZ MOBS 1 kW KW SEND S 521Bs TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-G 1,2K MOBS G1,2K+/- 10 WTT TELEF SENDER 10.34 S 318H Z 101 1500-3333 KHZ GUSS GEH SCHS 100 WTT SEND S 317H TELEFUNKEN Z 172 RS 31g 100-800METER alt SCHS S317H 100 WTT SENDER 4.33 S 317 H Z 101 UNIVERS SENDER 377-3000KHZ MOBS 15 W EINK SEND EMPF 10.35 Stat 272 B Z 101 +/- 15 W SE 469 SE 5285 F1/37 TRSE 15 WTT KARREN STN 4.40 SE 469A Z 101 3-5 MHZ TRSE 15 WTT KW STN 10.35 Spez804/445 Z 101 S= 804Bs E= Spez 445dBg 3-7,5M TRSE 150 WTT LANGW SENDE ANL 8.39 Stat 1006aF Z 101 S 427F SA 429F FLFU 1898-1938 40 JAAR RADIO IN NED SWIERSTRA R. Z 143 INLEGVEL VAN SWIERSTA PRIVE'38 LI 40 RADIO!! WILHELMINA 1kW KW SEND S 486F TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-2,5-7,5MHZ MOBS S486 1,5 LW SEND S 366Bs 11.37 S 366Bs Z 101 =+/- G1,5...100-600 KHZ MOBS 1,5kW LW SEND S366Bs TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-G 1,5L MOBS S366Bs S366BS 20 WTT FL STN 3.35 Spez 378mF Z 101 TELEF D B FLFU 20 WTT FLUGZEUG STN Spez 378nF TELEFUNKEN Z 172 URALT ANL LW FEST FREQU FLFU Spez378nF Spez378NF 20 WTT MITTELWELL GER Stat901 TELEFUNKEN Z 172 500-1500KHZ Stat 901A/F FLFU 200 WTT KW SEND AS 1008 11.39 AS 1008 Z 101 2,5-10 MHZ A1,A2,A3,HELL -

Ham Radio Magazine 1989

THE BATTLE OF THE BEAMS PART 1 By D. V. Pritchard, G4G VO, 55 Walker DL,Leigh on Beacon Dijhnen. Light Beacon after dark. Knickebein from Sea, Essex SS9 3QT, England 0600hr on 3159 Shortly afterwards, acooperative prisoner said that Knick- ebein was a beam so narrow and exact that two of them could pinpoint a target with an accuracy of less than a kilometer. He 1940...Now, nearly 50 years from those near-disastrous also added that Knickebein was in some ways similar to X- days, how many of us remember (or even know of) the debt Gergt, assuming that we were familiar with both systems! of gratitude owed to one man who confounded the radio From the wreck of another Heinkel, a diary was rushed to experts and overcame officialdom to earn Churchill's praise Jones. It read: March 5. Two-thirds of flight on leave. Afternoon as the man who "broke the bloody beams" - who went on training on Knickebein, collapsible boats, etc. to unravel the secrets of German radar and Hitler's "V By this time, the cryptographers at Bletchley Park had per- weapons," the V1 pilotless flying bomb (the 'tfoodlebug'] and formed a near miracle by breaklng the German Enigma code. the V2 rocket? One of the intercepted messagesfrom a German aircraft was sent to Jones: Knickebein, Kleve, is confirmed at position 53O24' north and lowest. This meant that the aircraft had orn in London in 1911, R. V. Jones was educated at reported receiving the beam a few miles south of Retford in St. -

An Assessment of the Development of Target Marking Techniques to the Prosecution of the Bombing Offensive During the Second World War

Circumventing the law that humans cannot see in the dark: an assessment of the development of target marking techniques to the prosecution of the bombing offensive during the Second World War Submitted by Paul George Freer to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in August 2017 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: Paul Freer 1 ABSTRACT Royal Air Force Bomber Command entered the Second World War committed to a strategy of precision bombing in daylight. The theory that bomber formations would survive contact with the enemy was soon dispelled and it was obvious that Bomber Command would have to switch to bombing at night. The difficulties of locating a target at night soon became apparent. In August 1941, only one in three of those crews claiming to have bombed a target had in fact had been within five miles of it. And yet, less than four years later, it would be a very different story. By early 1945, 95% of aircraft despatched bombed within 3 miles of the Aiming Point and the average bombing error was 600 yards. How, then, in the space of four years did Bomber Command evolve from an ineffective force failing even to locate a target to the formidable force of early 1945? In part, the answer lies in the advent of electronic navigation aids that, in 1941, were simply not available. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 49 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2010 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group Windrush House Avenue Two Station Lane Witney OX28 4XW 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice8President Air 2arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KC3 C3E AFC Committee Chairman Air 7ice82arshal N 3 3aldwin C3 C3E 7ice8Chairman -roup Captain 9 D Heron O3E Secretary -roup Captain K 9 Dearman FRAeS 2embership Secretary Dr 9ack Dunham PhD CPsychol A2RAeS Treasurer 9 3oyes TD CA 2embers Air Commodore - R Pitchfork 23E 3A FRAes ,in Commander C Cummin s :9 S Cox Esq 3A 2A :A72 P Dye O3E 3Sc(En ) CEn AC-I 2RAeS :-roup Captain 2 I Hart 2A 2A 2Phil RAF :,in Commander C Hunter 22DS RAF Editor & Publications ,in Commander C - 9efford 23E 3A 2ana er :Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS THE PRE8,AR DE7E.OP2ENT OF DO2INION AIR 7 FORCES by Sebastian Cox ANS,ERIN- THE @O.D COUNTRABSB CA.. by , Cdr 11 Colin Cummin s ‘REPEAT, PLEASE!’ PO.ES AND CCECHOS.O7AKS IN 35 THE 3ATT.E OF 3RITAIN by Peter Devitt A..IES AT ,ARE THE RAF AND THE ,ESTERN 51 EUROPEAN AIR FORCES, 1940845 by Stuart Hadaway 2ORNIN- G&A 76 INTERNATIONA. -

Jb-2: America's First Cruise Missile

JB-2: AMERICA’S FIRST CRUISE MISSILE Gary Francis Quigg Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University May 2014 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee ______________________________ Philip V. Scarpino, Ph.D., Chair ______________________________ Kevin C. Cramer, Ph.D. ______________________________ Elizabeth Brand Monroe, Ph.D., J.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the staff of each of the following institutions for their patience and dedication: National Archives and Records Administration II (College Park, Maryland, facility), Library of Congress, National Air and Space Museum, National Museum of the United States Air Force, and the history offices at three United States Air Force bases, Eglin, Maxwell, and Wright-Patterson. Two professionals from among these repositories deserve special recognition: Margaret Clifton, Research Specialist at the Library of Congress, and Major General Clay T. McCutchan (USAF Ret.), Historian in the Office of History at Eglin AFB. I am indebted to the Public History Program, especially my thesis committee. First, to Dr. Kevin C. Kramer, who was particularly helpful in suggesting the following publications: Dawning of the Cold War: The United States Quest for Order by Randall B. Woods and Howard Jones, The Cold War: A New History by John Lewis Gaddis, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era by Elaine Tyler May, The Culture of the Cold War by Stephen J. Whitfield, and Parting the Curtain: Propaganda, Culture and the Cold War, 1945-1961 by Walter L. -

The Halifax and Lancaster in Canadian Service

Canadian Military History Volume 15 Issue 3 Article 2 2006 The Halifax and Lancaster in Canadian Service Stephen J. Harris Directorate of Heritage and History, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Harris, Stephen J. "The Halifax and Lancaster in Canadian Service." Canadian Military History 15, 3 (2006) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harris: The Halifax and Lancaster The Halifax and Lancaster in Canadian Service Stephen J. Harris n our early discussions on the bomber section rate aircraft. I had to know how clapped out Iof The Crucible of War, the third volume of Halifaxes were; and I had to find out whether the official history of the Royal Canadian Air the allocation of aircraft was biased along Force, Ben Greenhous and I wondered whether national lines. What I found was that Harris we should adopt a chronological or topical exaggerated somewhat; that he did not allocate organisation. I preferred the latter; Ben the aircraft on national lines; and, perhaps not former. He was the principal author; he got his surprisingly, that bomber crews who survived a way – he was right, of course, I now admit freely; tour on Halifaxes were quite happy with their and his instructions to me were “to write an aircraft. Why not? They made it through.