The Halifax and Lancaster in Canadian Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II ORREST LEE “WOODY” VOSLER of Lyndonville, Quick Write New York, was a radio operator and gunner during F World War ll. He was the second enlisted member of the Army Air Forces to receive the Medal of Honor. Staff Sergeant Vosler was assigned to a bomb group Time and time again we read about heroic acts based in England. On 20 December 1943, fl ying on his accomplished by military fourth combat mission over Bremen, Germany, Vosler’s servicemen and women B-17 was hit by anti-aircraft fi re, severely damaging it during wartime. After reading the story about and forcing it out of formation. Staff Sergeant Vosler, name Vosler was severely wounded in his legs and thighs three things he did to help his crew survive, which by a mortar shell exploding in the radio compartment. earned him the Medal With the tail end of the aircraft destroyed and the tail of Honor. gunner wounded in critical condition, Vosler stepped up and manned the guns. Without a man on the rear guns, the aircraft would have been defenseless against German fi ghters attacking from that direction. Learn About While providing cover fi re from the tail gun, Vosler was • the development of struck in the chest and face. Metal shrapnel was lodged bombers during the war into both of his eyes, impairing his vision. Able only to • the development of see indistinct shapes and blurs, Vosler never left his post fi ghters during the war and continued to fi re. -

Aviation Classics Magazine

Avro Vulcan B2 XH558 taxies towards the camera in impressive style with a haze of hot exhaust fumes trailing behind it. Luigino Caliaro Contents 6 Delta delight! 8 Vulcan – the Roman god of fire and destruction! 10 Delta Design 12 Delta Aerodynamics 20 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan 62 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.6 Nos.1 and 2 64 RAF Scampton – The Vulcan Years 22 The ‘Baby Vulcans’ 70 Delta over the Ocean 26 The True Delta Ladies 72 Rolling! 32 Fifty years of ’558 74 Inside the Vulcan 40 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.3 78 XM594 delivery diary 42 Vulcan display 86 National Cold War Exhibition 49 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.4 88 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.7 52 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.5 90 The Council Skip! 53 Skybolt 94 Vulcan Furnace 54 From wood and fabric to the V-bomber 98 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.8 4 aviationclassics.co.uk Left: Avro Vulcan B2 XH558 caught in some atmospheric lighting. Cover: XH558 banked to starboard above the clouds. Both John M Dibbs/Plane Picture Company Editor: Jarrod Cotter [email protected] Publisher: Dan Savage Contributors: Gary R Brown, Rick Coney, Luigino Caliaro, Martyn Chorlton, Juanita Franzi, Howard Heeley, Robert Owen, François Prins, JA ‘Robby’ Robinson, Clive Rowley. Designers: Charlotte Pearson, Justin Blackamore Reprographics: Michael Baumber Production manager: Craig Lamb [email protected] Divisional advertising manager: Tracey Glover-Brown [email protected] Advertising sales executive: Jamie Moulson [email protected] 01507 529465 Magazine sales manager: -

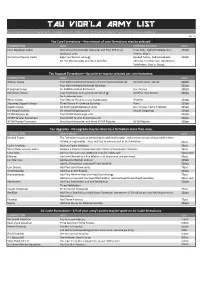

TAU VIOR'la ARMY LIST Tau Vior'la Armies Have a Strategy Rating of 3

TAU VIOR'LA ARMY LIST Tau Vior'la Armies have a Strategy Rating of 3. Crisis Battlesuit Cadres, XV014, KV128 and the Manta are Initiative 1+; all other formations are Initiative 2+. Dev 1.8 Tau Core Formations—Any amount of core formations may be selected. FORMATION UNITS UPGRADES ALLOWED COST Crisis Battlesuit Cadre One Shas'el Commander character and Four XV8 Crisis Crisis Suits, Cadre Fireblade, Gun 250pts Battlesuit units Drones, Shas'o Vior'la Fire Warrior Cadre Eight Fire Warrior units or Bonded Teams, Cadre Fireblade, 225pts Six Fire Warrior units and three Devilfish Ethereal, Fire Warriors, Gun Drones, Pathfinders, Shas'o, Skyray Tau Support Formations—Up to three may be selected per core formation. FORMATION UNITS COST Armour Group Four Hammerhead (Ionhead) or (Fusionhead) Gunships or Hammerheads, Skyray 200pts Four Hammerhead (Railhead) Gunships 225pts Broadside Group Six XV88 Broadside Battlesuits Gun Drones 300pts Pathfinder Group Four Pathfinder units and two Devilfish or Devilfish, Gun Drones 200pts Six Pathfinder units Recon Group Five Tetra or Piranha, in any combination Piranhas 150pts Skysweep Support Group Three Skyray Air Defence Gunships None 250pts Stealth Group Six XV15 Stealth Battlesuit units Gun Drones, Cadre Fireblade 225pts 0-2 Vespid Swarms Six Vespid Stingwing units Vespid Stingwings 150pts KX128 Stormsurge Two KX128 Stormsurge units 250pts KV129 Ta'unar Supremacy One KV129 Ta'unar Supremacy unit 225pts XV104 Riptide Formation One Shas'el character and three XV104 Riptides XV104 Riptide 350pts Tau Upgrades - No upgrade may be taken by a formation more than once. FORMATION UNITS / EFFECT COST Bonded Teams The formation counts as containing an additional Leader and removes an extra blast marker when rallying or regrouping. -

P-38J Over Europe 1170 US WWII FIGHTER 1:48 SCALE PLASTIC KIT

P-38J over Europe 1170 US WWII FIGHTER 1:48 SCALE PLASTIC KIT intro The Lockheed P-38 Lightning was developed to a United States Army Air Corps requirement. It became famous not only for its performance in the skies of WWII, but also for its unusual appearance. The Lightning, designed by the Lockheed team led by Chief Engineer Clarence 'Kelly' Johnson, was a complete departure from conventional airframe design. Powered by two liquid cooled inline V-1710 engines, it was almost twice the size of other US fighters and was armed with four .50 cal. machine guns plus a 20 mm cannon, giving the Lightning not only the firepower to deal with enemy aircraft, but also the capability to inflict heavy damage on ships. The first XP-38 prototype, 37-457, was built under tight secrecy and made its maiden flight on January 27, 1939. The USAAF wasn´t satisfied with the big new fighter, but gave permission for a transcontinental speed dash on February 11, 1939. During this event, test pilot Kelsey crashed at Mitchell Field, NY. Kelsey survived the cash but the airplane was written off. Despite this, Lockheed received a contract for thirteen preproduction YP-38s. The first production version was the P-38D (35 airplanes only armed with 37mm cannon), followed by 210 P-38Es which reverted back to the 20 mm cannon. These planes began to arrive in October 1941 just before America entered World War II. The next versions were P-38F, P-38G, P-38H and P-38J. The last of these introduced an improved shape of the engine nacelles with redesigned air intakes and cooling system. -

Local Lad Flies Into a Tree at Turvey

1940 LOCAL LAD FLIES INTO A TREE AT TURVEY Home Counties and instructors were told to keep training flights to a level LOCAL LAD FLIES INTO A where they would not interfere with operations. TREE AT TURVEY At 3.30pm on the afternoon of 7th October 1940, Jim Bridge took to the air in an Airspeed Oxford, N4729. His pupil James Bridge was born on 28th May 1914 was Leading Aircraftman Jack Kissner, th at 12 Egerton Road, Bexhill, Sussex, the son of 7 October 1940 a local lad from nearby Northampton. Walter and Mary Bridge. His family later moved Their task was to carry out a low flying LOCATION to Pavenham and, between 1923 and 1933, Jim practice flight around Cranfield. A few attended both Bedford Preparatory School and Newton Park Farm, Turvey moments after leaving the ground the small twin-engined aircraft struck a tree Bedford Modern School. He then went on to TYPE near the end of the runway and crashed attend Bedford Technical Institute and it was here, Airspeed Oxford I in October 1934, that Jim, with the support of his between the road and former railway line near Newton Park Farm, one mile south- employer, W. H. Allen Sons & Co. of Queens’ SERIAL No. south-west of the village of Turvey. The aircraft burst into flames on impact with N4729 the ground and the two crewmen died instantly. Engineering Works, Bedford, embarked on a Above right: Flying mechanical engineering course. On 1st October UNIT Officer James Bridge A subsequent Court of Inquiry found that pilot was flying less than 100 feet with his wife and new above the ground and had flown into bright sun, which hampered his vision. -

HANDLEY PAGE HAMPDEN BOMBER X3023 Templewood Is A

HANDLEY PAGE HAMPDEN BOMBER X3023 Templewood is a grade II listed building located near Northrepps in Norfolk. It was built as a shooting box in 1938/39 for senior conservative politician Sir Samuel Hoare, Lord Templewood, who served in several cabinet posts including that of Secretary of State for Air in the 1920’s. The calm of the countryside was shattered when at 06.20hrs on the 20th November 1940 whilst still dark and in severe weather Hampden Bomber X3023 of No 44 Squadron based at RAF Waddington crashed about 200 yards from Templewood and caught fire. The aircraft was returning from a bombing mission in central Germany. Suffering severe damage and flying on one engine in atrocious weather, the pilot Sergeant Jack Ottaway displayed supreme airmanship in flying the aircraft over the North Sea and reaching the coast. However he finally lost control and crashed in a wooded area and was killed along with the navigator Pilot Officer Archie Kerr and wireless operator/air gunner Sergeant Stanley Elliott. A further air gunner Sergeant Stanley Hird survived the crash and served to the end of the war as a Flying Officer having been awarded the DFC. The Memorial Following a well researched paper on the detail of the crash written by James Mindham a local historian who had discovered the site of the crash and evidence from the aircraft wreckage, the current owner of Templewood, Eddie Anderson a Film Producer, decided to erect on the spot a memorial to X3023 and its crew in the form of a tree stump and commemorative plate. -

Vickers Armstrong Wellington.Pdf

FLIGHT, July 6. 1939. a Manoeuvrability is an outstanding quality of the Wellington. CEODETICS on the GRAND SCALE A Detailed Description of the Vickers-Armstrongs Wellington I : Exceptional Range and Large Bomb Capacity : Ingenious Structural Features (Illustrated mainly with "Flight" Photographs and Sketches) T is extremely unlikely that any foreign air force in place of the Pegasus XVIIIs); it has provision for five possesses bombers with as long a range as that attain turreted machine-guns; it is quite exceptionally roomy, I able by the Vickers-Armstrongs Wellington I (Type and it is amazingly agile in the air. 290), which forms the equipment of a number of The Bristol Pegasus XVIII engines fitted as standard in squadrons of the Royal Air Force and of which it is now permissible to dis close structural details. The Wellington's capa city for carrying heavy loads over great distances may be directly attributed to the Vickers geodetic system of construction, which proved its worth in the single-engined Welles- ley used" as standard equipment in a number of overseas squadrons of the R.A.F. But the qualities of the Wellington are not limited to load-carrying. It has a top speed of 265 m.p.h. (or consider ably more when fitted with Rolls-Royce Merlin or Bristol Hercules engines The Wellington, with its ex tremely long range, has comprehensive tankage ar rangements. The tanks (riveted by the De Bergue system) taper in conformity with the wing. FLIGHT, July 6, 1939. The rear section of the fuselage, looking toward the tail turret, with the chute for the reconnaissance flaref protuding on ihe left amidships. -

Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War PRINTER: strip in FIGURE NUMBER A-1 Shoot at 277% bleed all sides Stephen L. McFarland A Douglas P–70 takes off for a night fighter training mission, silhouetted by the setting Florida sun. 2 The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War Stephen L. McFarland AIR FORCE HISTORY AND MUSEUMS PROGRAM 1998 Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War The author traces the AAF’s development of aerial night fighting, in- cluding technology, training, and tactical operations in the North African, European, Pacific, and Asian theaters of war. In this effort the United States never wanted for recruits in what was, from start to finish, an all-volunteer night fighting force. Cut short the night; use some of it for the day’s business. — Seneca For combatants, a constant in warfare through the ages has been the sanctuary of night, a refuge from the terror of the day’s armed struggle. On the other hand, darkness has offered protection for operations made too dangerous by daylight. Combat has also extended into the twilight as day has seemed to provide too little time for the destruction demanded in modern mass warfare. In World War II the United States Army Air Forces (AAF) flew night- time missions to counter enemy activities under cover of darkness. Allied air forces had established air superiority over the battlefield and behind their own lines, and so Axis air forces had to exploit the night’s protection for their attacks on Allied installations. -

A Tribute to Bomber Command Cranwellians

RAF COLLEGE CRANWELL “The Cranwellian Many” A Tribute to Bomber Command Cranwellians Version 1.0 dated 9 November 2020 IBM Steward 6GE In its electronic form, this document contains underlined, hypertext links to additional material, including alternative source data and archived video/audio clips. [To open these links in a separate browser tab and thus not lose your place in this e-document, press control+click (Windows) or command+click (Apple Mac) on the underlined word or image] Bomber Command - the Cranwellian Contribution RAF Bomber Command was formed in 1936 when the RAF was restructured into four Commands, the other three being Fighter, Coastal and Training Commands. At that time, it was a commonly held view that the “bomber will always get through” and without the assistance of radar, yet to be developed, fighters would have insufficient time to assemble a counter attack against bomber raids. In certain quarters, it was postulated that strategic bombing could determine the outcome of a war. The reality was to prove different as reflected by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris - interviewed here by Air Vice-Marshal Professor Tony Mason - at a tremendous cost to Bomber Command aircrew. Bomber Command suffered nearly 57,000 losses during World War II. Of those, our research suggests that 490 Cranwellians (75 flight cadets and 415 SFTS aircrew) were killed in action on Bomber Command ops; their squadron badges are depicted on the last page of this tribute. The totals are based on a thorough analysis of a Roll of Honour issued in the RAF College Journal of 2006, archived flight cadet and SFTS trainee records, the definitive International Bomber Command Centre (IBCC) database and inputs from IBCC historian Dr Robert Owen in “Our Story, Your History”, and the data contained in WR Chorley’s “Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War, Volume 9”. -

No. 138 Squadron Arrived Flying Whitleys, Halifaxes and Lysanders Joined the Following Month by No

Life Of Colin Frederick Chambers. Son of Frederick John And Mary Maud Chambers, Of 66 Pretoria Road Edmonton London N18. Born 11 April 1917. Occupation Process Engraver Printing Block Maker. ( A protected occupation) Married 9th July 1938 To Frances Eileen Macbeath. And RAFVR SERVICE CAREER OF Sergeant 656382 Colin Frederick Chambers Navigator / Bomb Aimer Died Monday 15th March 1943 Buried FJELIE CEMETERY Sweden Also Remembered With Crew of Halifax DT620-NF-T On A Memorial Stone At Bygaden 37, Hojerup. 4660 Store Heddinge Denmark Father Of Michael John Chambers Grandfather Of Nathan Tristan Chambers Abigail Esther Chambers Matheu Gidion Chambers MJC 2012/13 Part 1 1 Dad as a young boy with Mother and Grandmother Dad at school age outside 66 Pretoria Road Edmonton London N18 His Father and Mothers House MJC 2012/13 Part 1 2 Dad with his dad as a working man. Mum and Dad’s Wedding 9th July 1938 MJC 2012/13 Part 1 3 The full Wedding Group Dad (top right) with Mum (sitting centre) at 49 Pembroke Road Palmers Green London N13 where they lived. MJC 2012/13 Part 1 4 After Volunteering Basic Training Some Bits From Dads Training And Operational Scrapbook TRAINING MJC 2012/13 Part 1 5 Dad second from left, no names for rest of people in photograph OPERATIONS MJC 2012/13 Part 1 6 The Plane is a Bristol Blenheim On leave from operations MJC 2012/13 Part 1 7 The plane is a Wellington Colin, Ken, Johnny, Wally. Before being posted to Tempsford Navigators had to served on at least 30 operations. -

Abstracts from the Scientific and Technical Press Titles And

December, ig4j Abstracts from the Scientific and Technical Press " (No. 117. October, 1943) AND Titles and References of Articles and Papers Selected from Publications (Reviewed by R.T.P.3) TOGETHER WITH List of Selected Translations (No. 63)' London : "THE ROYAL AERONAUTICAL SOCIETY" with which is incorporated "The Institution of Aeronautical Engineers" 4, Hamilton Place, W.I Telephone: Grosvenor 3515 (3 lines) ABSTRACTS FROM THE SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL PRESS. Issued by the Directorate's of Scientific Research and Technical Development, Ministry of Air craft Production. (Prepared by R.T.P.3.) No. 117. OCTOBER, 1943. Notices and abstracts from the Scientific and Technical Press are prepared primarily for_ the information of Scientific and Technical Staffs. Particular attention is paid to the work carried out in foreign countries, on the assumption that the more accessible British work (for example that published by the Aeronautical Research Committee^ is already known to these Staffs. Requests from scientific and technical staffs for further information of transla tions should be addressed to R.T,P.3, Ministry of Aircraft Production, and not to the Royal Aeronautical Society. Only a limited number of the articles quoted from foreign journals are trans lated and usually only the original can be supplied on loan. If, however, translation is required, application should be made in writing to R.T.P.3, the requests being considered in accordance with existing facilities. ' NOTE.—As far as possible, the country of origin quoted in the items refers to the original source. The Effect of Nitrogen on the Properties of Certain Austenitic Valve Steels. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES