Singing the South Downs Way: Affect in Performance and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Booklet

“I am one of the last of a small tribe of troubadours who still believe that life is a beautiful and exciting journey with a purpose and grace well worth singing about.” E Y Harburg Purpose + Grace started as a list of songs and a list of possible guests. It is a wide mixture of material, from a traditional song I first heard 50 years ago, other songs that have been with me for decades, waiting to be arranged, to new original songs. You stand in a long line when you perform songs like this, you honour the ancestors, but hopefully the songs become, if only briefly your own, or a part of you. To call on my friends and peers to make this recording has been a great pleasure. Turning the two lists into a coherent whole was joyous. On previous recordings I’ve invited guest musicians to play their instruments, here, I asked singers for their unique contributions to these songs. Accompanying song has always been my favourite occupation, so it made perfect sense to have vocal and instrumental collaborations. In 1976 I had just released my first album and had been picked up by a heavy, old school music business manager whose avowed intent was to make me a star. I was not averse to the concept, and went straight from small folk clubs to opening shows for Steeleye Span at the biggest halls in the country. Early the next year June Tabor asked me if I would accompany her on tour. I was ecstatic and duly reported to my manager, who told me I was a star and didn’t play for other people. -

Armandito Y Su Trovason High Energy Cuban Six Piece Latin Band

Dates For Your Diary Folk News Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Dance News Issue 412 CD Reviews November 2009 $3.00 Armandito Y Su Trovason High energy Cuban six piece Latin band ♫ folk music ♫ dance ♫ festivals ♫ reviews ♫ profiles ♫ diary dates ♫ sessions ♫ teachers ♫ opportunities The Folk Federation ONLINE - jam.org.au The CORNSTALK Gazette NOVEMBER 2009 1 AdVErTISINg Rates Size mm Members Non-mem NOVEMBEr 2009 Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Full page 180x250 $80 $120 In this issue Post Office Box A182 1/2 page 180x125 $40 $70 Dates for your diary p4 Sydney South NSW 1235 ISSN 0818 7339 ABN9411575922 1/4 page 90x60 $25 $50 Festivals, workshops, schools p6 jam.org.au 1/8 page 45 x 30 $15 $35 Folk news p8 The Folk Federation of NSW Inc, formed in Back cover 180x250 $100 $150 Dance news p9 1970, is a Statewide body which aims to present, Folk contacts p10 support, encourage and collect folk m usic, folk 2 + issues per mth $90 $130 dance, folklore and folk activities as they exist Advertising artwork required by 5th of each month. CD Review p14 Advertisements can be produced by Cornstalk if re- in Australia in all their forms. It provides a link quired. Please contact the editor for enquiries about Deadline for December/January Issue for people interested in the folk arts through its advertising Tel: 6493 6758 ADVERTS 5th November affiliations with folk clubs throughout NSW and its Inserts for Cornstalk COPY 10th November counterparts in other States. It bridges all styles [email protected] NOTE: There will be no January issue. -

Mitchell Brothers – Vaudeville and Western

Vaudeville and the Last Encore By Marlene Mitchell February, 1992 William Mitchell, his wife Pearl Mitchell, and John Mitchell 1 Vaudeville and the Last Encore By Marlene Mitchell February, 1992 Vaudeville was a favorite pastime for individuals seeking clean entertainment during the early part of the 20th century. The era of vaudeville was relatively short because of the creation of new technology. Vaudeville began around 1881 and began to fade in the early 1930s.1 The term vaudeville originated in France.2 It is thought that the term vaudeville was from “Old French vaudevire, short for chanson du Vaux de Vire, which meant popular satirical songs that were composed and presented during the 15th century in the valleys or vaux near the French town of Vire in the province of Normandy.”3 How did vaudeville begin? What was vaude- ville’s purpose and what caused its eventual collapse? This paper addresses the phenomenon of vaudeville — its rise, its stable but short lifetime, and its demise. Vaudeville was an outgrowth of the Industrial Revolution, which provided jobs for peo- ple and put money in their pockets.4 Because of increased incomes, individuals began to desire and seek clean, family entertainment.5 This desire was first satisfied by Tony Pastor, who is known as the “father of vaudeville.”6 In 1881 Pastor opened “Tony Pastor’s New Fourteenth Street Theatre” and began offering what he called variety entertainment.7 Later B. F. Keith, who is called the “founder of vaudeville,” opened a theater in Boston and expanded on Pastor’s original variety concept.8 Keith was the first to use the term “vaudeville” when he opened his theater in Boston in 1894.9 Keith later joined with E. -

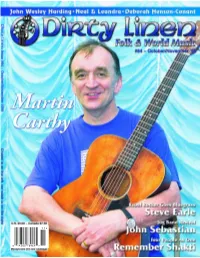

14302 76969 1 1>

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

Topic Records 80Th Anniversary Start Time: 8Pm Running Time: 2 Hours 40 Minutes with Interval

Topic Records 80th Anniversary Start time: 8pm Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston discusses the history behind the world’s oldest independent label ahead of this collaborative performance. When Topic Records made its debut in 1939 with Paddy Ryan’s ‘The Man That Waters The Workers’ Beer’, an accordion-backed diatribe against capitalist businessmen who underpay their employees, it’s unlikely that anyone involved was thinking of the future – certainly not to 2019, when the label celebrates its 80th birthday. In any case, the future would have seemed very precarious in 1939, given the outbreak of World War II, during which Topic ceased most activity (shellac was particularly hard to source). But post-1945, the label made good on its original brief: ‘To use popular music to educate and inform and improve the lot of the working man,’ explains David Suff, the current spearhead of the world’s oldest independent label – and the undisputed home of British folk music. Tonight at the Barbican (where Topic held their 60th birthday concerts), musical director Eliza Carthy – part of the Topic recording family since 1997, though her parents Norma Waterson and Martin Carthy have been members since the sixties and seventies respectively - has marshalled a line-up to reflect the passing decades, which hasn’t been without its problems. ‘We have far too much material, given it’s meant to be a two-hour show!’ she says. ‘It’s impossible to represent 80 years – you’re talking about the left-wing leg, the archival leg, the many different facets of society - not just communists but farmers and factory workers - and the folk scene in the Fifties, the Sixties, the Seventies.. -

Historical Sketches of Savage Life in Polynesia; with Illustrative Clan Songs

LIFE 11 r \ V ^VY THE .W.W.GILL.B.A. s^i*v iHilNiiaiHiliA -^ V:»-y*Vi .^^Mtfwjjtooiffn., !'#:j,;_>_'-i3S*!ii.ilEit«St-»4f J»»,J vriL-«r--r the estf.te of the late William Edward Kelley / HISTORICAL SKETCHES OF SAVAGE LIFE IN POLYNESIA. : HISTORICAL SKETCHES OP SAVAGE LIFE IN POLYNESIA: WITH ILLUSTRATIVE CLAN SONGS. BY THB REV. WILLIAM WYATT GILL, BA., AUTHOR OF "MYTHS AND SONGS FEOM THE SOUTH PACIFIC. WELLINGTON GEORGE DIDSBURY, GOVERNMENT PRINTER. 1880. LIBRARY 731325 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO — INTRODUCTORY REMARKS. The flattering reception accorded to a former^ volume has induced me to collect and publish a series of Historical Sketches with Illustrative Songs, which may not be without interest to students of ethnology and others. Some of them have already appeared in a serial publication. During a long residence on Mangaia, shut out to a great extent from the civilized world, I enjoyed great facilities for the study of the natives themselves and their traditions. I soon found that they had two sets of traditions — one referring to their gods, and to the supposed experiences of men after death; another relating veritable history. The natives themselves carefully distinguish the two. Thus, historical songs are called '^ pe^e ;^' the others, ^^ kapa,'^ &c. In the native mind the series now presented to the English public is a natural sequence to " Myths and Songs ;" the mythical, or, as they would say, the spiritual, necessarily taking precedence of the historical or human. In such researches we cannot be too careful to distinguish history from myth. But when we find hostile clans, in their epics, giving substantially the same account of the historical past, the most sceptical must yield to the force of evidence. -

Volume 38, Number 09 (September 1920) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 9-1-1920 Volume 38, Number 09 (September 1920) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 38, Number 09 (September 1920)." , (1920). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/672 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE Presser’s Musical Magazine MUSIC COMPOSITION FOR WOMEN BY CARRE JACOBS-BOND ULTRA-MODERN MUSIC EXPLAINED BY PROFESSOR CHARLES QUEF KEYBOARD MASTERY BY CONSTANTIN STERNBERG WHY UNDERPAY THE MUSIC TEACHER? BY CHARLES E. WATT HOW HAYDN SUCCEEDED BY COMMENDATORE E. di PIRANI $2.00 A YEAR THE EjTUDE SEPTEMBER 1920 Page 577 This TRADE MARK 'Represenhs Lhe BEST Lhere is in Beautiful Balladv Smil/nThittOUGH ( Sacred - Secular ) Solos - Duets - Quartete r%gj THEY SONGS G;i? C / I* *V>* ' CAN AND MORE 5°*G „ / ARE I/S , BE OtWllTTltBOYQfMlNf S«S£„. &-*£? AT T: °A iJjev*. ri»e* '**». /PLAYED CONG «««** ON A>f 9 ■0 2-4, , PIANO Evening Brings Rest DjARD/ ' G^f„ And you /or ORGAN *e ' 50 Wes Tb*^tefi each like *5'”' / IDEAL FOR THIS IT I^^SSCE?* 'the HOME ACTUAL SIZE / 6 by 9 Inches CONCERT MAUMUSUNfUWaS-fiOOON'OHl SENT /and CHURCH on requeshy IF YOU LOVE A GOOD enclosej BALLAD 5 cents i H°WONETm in stan ( SACRED or SECULAR) . -

Egister Volume Lxix, No

EGISTER VOLUME LXIX, NO. 30. EED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, JANXTARY .16, 1947 SECTION ONE—PAGES 1. TO The Register Again Red Bank Savings Father And Daughter ^acred Concert Monmouth PaYk Gets Heads The List Killed By Train Triplets, All Boys, ] A sample check up'.of 49 of the And Loan Ass'n Word, has been received of the Sunday Night In better weekly newspapers of the sudden passing of Worth Rhodes June 19 -July 30 Date nation, all members of the Audit Has Good Year Bushnell, 42, and his soven-year-old For Episcopal Rector Bureau of Circulation and the daughter Parmly of Mendenhall, Methodist Church Greater Weeklies division of the Pa., who were instantly killed Sat- American Press association, shows Statement By Its urday, January 4, near their home. Elizabeth Waddell Local-Track Is In Excellent Shape— that the average of this group .ran Mr. Busnell and his daughter were Rev. And Mrs. Spofford, Jr., 6,117 lines of national advertising President Offered To in their car and stopped at a cross- Of Fair Haven Is during November. They ranged ing to allow a train to go by. just Are The Proud Parents • . Racing Commission Issues Schedule torn a high of 20,207 lines to a low Tho Public as the train approached tho cross- Soloist Of Evening of 1,358 lines. ing the Bushnell car suddenly •+• Timothy Spofford, 15-montl Monmouth Park will. open its It is pleasing to the publisher Assets of the Red Bank Sayings sprang ahc^d right In front of the A sacred concert sponsored , by son of Rev. -

The Watersons the Definitive Collection Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Watersons The Definitive Collection mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: The Definitive Collection Country: UK Released: 2003 Style: Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1203 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1609 mb WMA version RAR size: 1410 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 881 Other Formats: AHX AUD MP4 AU MP1 MMF DTS Tracklist 1 God Bless The Master 3:05 2 Dido Bendigo 2:53 3 The Welcome Sailor 3:12 4 Emmanuel 2:48 5 Idumea 1:48 6 The Still And Silent Ocean 4:25 7 Fathom The Bowl 2:52 8 Fare Thee Well Cold Winter 2:32 9 The Holmfirth Anthem 1:58 10 Stormy Winds 3:10 11 Rosebuds In June 3:15 12 Bellman 3:55 13 Sleep On Beloved 3:03 14 Swansea Town 4:18 15 The Beggar Man 3:26 16 Amazing Grace 4:38 17 The Old Churchyard 3:23 18 Adieu Sweet Lovely Nancy 3:38 19 Malpas Wassail 4:11 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Topic Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Topic Records Ltd. Licensed From – Topic Records Ltd. Published By – Concorde International Management Consultants Ltd. Published By – Gwyneth Music Ltd. Published By – Topic Records Ltd. Published By – MCS Music Limited Published By – Free Reed Music Published By – April Music Ltd. Published By – Mole Music Ltd Credits Accompanied By – Gabriel's Horns (tracks: 4) Concertina [Anglo-concertina] – Tony Engle (tracks: 15) Fiddle – Peta Webb (tracks: 15) Guitar – Martin Carthy Melodeon – Rod Stradling (tracks: 15) Performer – Anthea Bellamy (tracks: 16), Barry Coope (tracks: 18), Blue Murder (tracks: 18), Eliza Carthy (tracks: 13, 17, 18), Jim Boyes (tracks: 18), Jim -

Billboard-1997-07-19

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) IN MUSIC NEWS IBXNCCVR **** * ** -DIGIT 908 *90807GEE374EM002V BLBD 589 001 032198 2 126 1200 GREENLY 3774Y40ELMAVEAPT t LONG BEACH CA 90E 07 Debris Expects Sweet Success For Honeydogs PAGE 11 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT ADVERTISEMENTS RIAA's Berman JAMAICAN MUSIC SPAWNS Hit Singles Is Expected To DRAMATIC `ALTERNATIVES' Catapult Take IFPI Helm BY ELENA OUMANO Kingston -based label owner /artist manager Steve Wilson, former A &R/ Colvin, Robyn This story was prepared by Ad f , Mention "Jamaica" and most people promotion manager for Island White in London and Bill Holland i, think "reggae," the signature sound of Jamaica. "It means alternative to BY CHUCK TAYLOR Washington, D.C. that island nation. what's traditionally Jamaicans are jus- known as Jamaican NEW YORK -One is a seasoned tifiably proud of music. There's still veteran and the other a relative their music's a Jamaican stamp Put r ag top down, charismatic appeal on the music. The light p the barbet Je and its widespread basslines and drum or just enjoy the sunset influence on other beats sound famil- cultures and iar. But that's it. featuring: tfri musics. These days, We're using a lot of Coen Bais, Abrazas N all though, more and GIBBY FAHRENHEIT blues, funk, jazz, Paul Ventimiglia, LVX Nava BERMAN more Jamaicans folk, Latin, and a and Jaquin.liévaao are refusing to subsume their individ- lot of rock." ROBYN COLVIN BILLBOARD EXCLUSIVE ual identities under the reggae banner. -

Biography of Pir-O-Murshid Inayat Khan

Biography of Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan Part I. Biography (1st part) Part I. Biography (2nd part) Part II. Autobiography Part III. Journal Anecdotes & Epilogue Biographical Sketches of Principal Workers Notes and Glossary (Notes are indicated by asterisk: *) Please note: This ebook does not include any of the reference materials or illustrations of the original paper edition. Biography of Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan Part I. Biography India in 1882 Towards the middle of the latter half of the 19th century, a desire for religious and social reform was awakening in India among Hindus and Moslims alike. Centuries earlier, Shankaracharya * had turned the tide of religious feeling towards a greater spirituality. Both Nanak *, the great Guru * of the Sikhs *, and Kabir *, the poet, had created and left in the land a living spirit of tolerance in religion and of spiritual purity. A fresh fire was given to religious life by the great sages Dadu * and Sundar *. More recently the religious association Arya Samaj * had been founded by Dayananda Saraswati *, the religious reform of Swami Narayan * had been made, Devendranath Tagore * had lighted a new flame of religion in Brahmo Samj *. Then Mirza Ghulam Hussein Qadiani [The full name is Mirza Ghulam Hussein Ahmad Qadiani] had set on foot the Ahmadia Movement *, the Christian missionaries were endeavouring to propagate Christianity and the Theosophical Society * had established itself as The Hindu College at Benares. The dark clouds that had hung over the land in the years following the Mutiny *, were breaking. on the one hand Sir Sayyed Ahmad * was working to induce the Moslims to make the best of existing conditions, in particular by the foundation of Aligarh College * and to arouse in the Moslim youth a spirit of enterprise, energy and self-dependence and on the other hand the British Government was setting to work at reform in law, education and administration. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: 13 May 2002 I, Amber Good , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Music in: Music History It is entitled: ``Lady, What Do You Do All Day?'': Peggy Seeger's Anthems of Anglo-American Feminism Approved by: Dr. bruce mcclung Dr. Karin Pendle Dr. Stephanie P. Schlagel 1 “LADY, WHAT DO YOU DO ALL DAY?”: PEGGY SEEGER’S ANTHEMS OF ANGLO-AMERICAN FEMINISM A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2002 by Amber Good B.M. Vanderbilt University, 1997 Committee Chair: Dr. bruce d. mcclung 2 ABSTRACT Peggy Seeger’s family lineage is indeed impressive: daughter of composers and scholars Charles and Ruth Crawford Seeger, sister of folk icons Mike and Pete Seeger, and widow of British folksinger and playwright Ewan MacColl. Although this intensely musical genealogy inspired and affirmed Seeger’s professional life, it has also tended to obscure her own remarkable achievements. The goal of the first part of this study is to explore Peggy Seeger’s own history, including but not limited to her life within America’s first family of folk music. Seeger’s story is distinct from that of her family and even from that of most folksingers in her generation. The second part of the thesis concerns Seeger’s contributions to feminism through her songwriting, studies, and activism.