Rearguard of the Revolution: MI5, Communism and British Musicians Introduction SLIDE 2 This Paper Starts with What Might Seem A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Booklet

“I am one of the last of a small tribe of troubadours who still believe that life is a beautiful and exciting journey with a purpose and grace well worth singing about.” E Y Harburg Purpose + Grace started as a list of songs and a list of possible guests. It is a wide mixture of material, from a traditional song I first heard 50 years ago, other songs that have been with me for decades, waiting to be arranged, to new original songs. You stand in a long line when you perform songs like this, you honour the ancestors, but hopefully the songs become, if only briefly your own, or a part of you. To call on my friends and peers to make this recording has been a great pleasure. Turning the two lists into a coherent whole was joyous. On previous recordings I’ve invited guest musicians to play their instruments, here, I asked singers for their unique contributions to these songs. Accompanying song has always been my favourite occupation, so it made perfect sense to have vocal and instrumental collaborations. In 1976 I had just released my first album and had been picked up by a heavy, old school music business manager whose avowed intent was to make me a star. I was not averse to the concept, and went straight from small folk clubs to opening shows for Steeleye Span at the biggest halls in the country. Early the next year June Tabor asked me if I would accompany her on tour. I was ecstatic and duly reported to my manager, who told me I was a star and didn’t play for other people. -

Mick Evans Song List 1

MICK EVANS SONG LIST 1. 1927 If I could 2. 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Here Without You 3. 4 Non Blondes What’s Going On 4. Abba Dancing Queen 5. AC/DC Shook Me All Night Long Highway to Hell 6. Adel Find Another You 7. Allan Jackson Little Bitty Remember When 8. America Horse with No Name Sister Golden Hair 9. Australian Crawl Boys Light Up Reckless Oh No Not You Again 10. Angels She Keeps No Secrets from You MICK EVANS SONG LIST Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again 11. Avicii Hey Brother 12. Barenaked Ladies It’s All Been Done 13. Beatles Saw Her Standing There Hey Jude 14. Ben Harper Steam My Kisses 15. Bernard Fanning Song Bird 16. Billy Idol Rebel Yell 17. Billy Joel Piano Man 18. Blink 182 Small Things 19. Bob Dylan How Does It Feel 20. Bon Jovi Living on a Prayer Wanted Dead or Alive Always Bead of Roses Blaze of Glory Saturday Night MICK EVANS SONG LIST 21. Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the dark I’m on Fire My Home town The River Streets of Philadelphia 22. Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Heaven Run to You Cuts Like A Knife When You’re Gone 23. Bush Glycerine 24. Carly Simon Your So Vein 25. Cheap Trick The Flame 26. Choir Boys Run to Paradise 27. Cold Chisel Bow River Khe Sanh When the War is Over My Baby Flame Trees MICK EVANS SONG LIST 28. Cold Play Yellow 29. Collective Soul The World I know 30. Concrete Blonde Joey 31. -

A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 30 2004 A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Keith, Thomas (2004) "A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol33/iss1/30 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Keith A Discography of Robert Bums 1948 to 2002 After Sir Walter Scott published his edition of border ballads he came to be chastised by the mother of James Hogg, one Margaret Laidlaw, who told him: "There was never ane 0 my sangs prentit till ye prentit them yoursel, and ye hae spoilt them awthegither. They were made for singing an no forreadin: butye hae broken the charm noo, and they'll never be sung mair.'l Mrs. Laidlaw was perhaps unaware that others had been printing Scottish songs from the oral tradition in great numbers for at least the previous hundred years in volumes such as Allan Ramsay's The Tea-Table Miscellany (1723-37), Orpheus Caledonius (1733) compiled by William Thompson, James Oswald's The Cale donian Pocket Companion (1743, 1759), Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs (1767, 1770) edited by David Herd, James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum (1787-1803) and A Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs (1793-1818) compiled by George Thompson-substantial contributions having been made to the latter two collections by Robert Burns. -

Armandito Y Su Trovason High Energy Cuban Six Piece Latin Band

Dates For Your Diary Folk News Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Dance News Issue 412 CD Reviews November 2009 $3.00 Armandito Y Su Trovason High energy Cuban six piece Latin band ♫ folk music ♫ dance ♫ festivals ♫ reviews ♫ profiles ♫ diary dates ♫ sessions ♫ teachers ♫ opportunities The Folk Federation ONLINE - jam.org.au The CORNSTALK Gazette NOVEMBER 2009 1 AdVErTISINg Rates Size mm Members Non-mem NOVEMBEr 2009 Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Full page 180x250 $80 $120 In this issue Post Office Box A182 1/2 page 180x125 $40 $70 Dates for your diary p4 Sydney South NSW 1235 ISSN 0818 7339 ABN9411575922 1/4 page 90x60 $25 $50 Festivals, workshops, schools p6 jam.org.au 1/8 page 45 x 30 $15 $35 Folk news p8 The Folk Federation of NSW Inc, formed in Back cover 180x250 $100 $150 Dance news p9 1970, is a Statewide body which aims to present, Folk contacts p10 support, encourage and collect folk m usic, folk 2 + issues per mth $90 $130 dance, folklore and folk activities as they exist Advertising artwork required by 5th of each month. CD Review p14 Advertisements can be produced by Cornstalk if re- in Australia in all their forms. It provides a link quired. Please contact the editor for enquiries about Deadline for December/January Issue for people interested in the folk arts through its advertising Tel: 6493 6758 ADVERTS 5th November affiliations with folk clubs throughout NSW and its Inserts for Cornstalk COPY 10th November counterparts in other States. It bridges all styles [email protected] NOTE: There will be no January issue. -

Christy Moore and the Irish Protest Ballad

“Ordinary Man”: Christy Moore and the Irish Protest Ballad MIKE INGHAM Introduction: Contextualizing the Modern Ballad In his critical study, The Long Revolution, Raymond Williams identified three definitions of culture, namely idealist, documentary, and social. He conceives of them as integrated strands of a holistic, organic cultural process pertaining to the “common associative life”1 of which creative artworks are an inalienable part. His renowned “structure of feeling” concept is closely related to this theoretical paradigm. The ballad tradition of popular and protest song in many ethnic cultural traditions exemplifies the core of Williams’s argument: it synthesizes the ideal aesthetic of the traditional folk song form as cultural production, the documentary element of the people, places, and events that the song records and the contextual resonances of the ballad’s source and target cultures. Likewise, the persistence and durability of the form over many centuries have ensured its survival as a rich source for ethnographic studies and an index of prevailing socio-political conditions and concerns. As twentieth-century commentators on the Anglophone ballad form, such as A. L. Lloyd, have observed, there is an evident distinction between the older ballad tradition, tending toward a more impersonal and distanced voice and perspective, and the more personal style of ballad composed after the anthropological research of ethnomusicologists such as Cecil Sharp, Alan Lomax, and others during the first half of the twentieth century. The former derives from a continuous lineage of predominantly anonymous or unattributed folk material that can be said to reside in the public domain, and largely resists recuperation or commodification by the music industry. -

List of Additional Human Rights Songs

THE POWER OF OUR VOICES LIST OF ADDITIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS SONGS This is a list of additional songs linked to human rights issues for teachers who want to expand the topics covered in the lessons. Joan Baez and Mimi Farina The Clash Bread and roses (1976) Know your rights (1982) Women’s liberation song, inspired by the ‘Know your rights all 3 of them… women textile workers’ strike in Massachusetts Number three: You have the right to free in 1912. Speech as long as you’re not Dumb enough to actually try it. Band Aid Know your rights Do they know it’s Christmas? (1984) These are your rights’ Song to raise money for the 1983-1985 famine in Ethiopia. Sam Cooke A change is gonna come (1964) Ludwig van Beethoven On discrimination and racism in 1960s USA. O Welche Lust (1775) The prisoner’s chorus from his opera about a Dire Straits prisoner of conscience jailed for his ideas. Brothers in arms (1985) Anti-war song. Billy Bragg Between the wars (1984) Bob Dylan Song about class division. Only a pawn in their game (1963) Which side are you on? (1984) Song about the racist murder of Medgar Evans, A version of a traditional union song. civil rights campaigner in Mississippi. Joe Hill (1990) Hurricane (1966) Song about a murdered union organiser. Song about Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter, a boxer who spent 19 years in jail for a murder Dylan felt Big Bill Broonzy he did not commit. Black, brown and white blues (1939) Masters of war (1966) Song about racial discrimination in the jobs Song against war and the power of the military- market. -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

14302 76969 1 1>

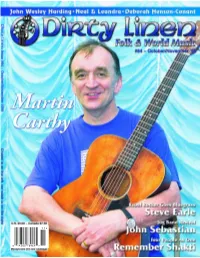

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986 Cecilia Peterson, Greg Adams, Jeff Place, Stephanie Smith, Meghan Mullins, Clara Hines, Bianca Couture 2014 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1942-1987 (bulk 1947-1987)........................................ 5 Series 2: Folkways Production, 1946-1987 (bulk 1950-1983).............................. 152 Series 3: Business Records, 1940-1987.............................................................. 477 Series 4: Woody Guthrie -

The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors Since the 1960’S

1 The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors Since the 1960’s Francesca Mary Greatorex Theatre and Performance Department Goldsmiths University of London A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: ……………………………………………. 3 Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been written without the generosity of many individuals who were kind enough to share their knowledge and theatre experience with me. I have spoken with actors, musical directors, set designers, directors, singers, choreographers and actor-musicians and their names and testaments exist within the thesis. I should like to thank Emily Parsons the archivist for the Liverpool Everyman for all her help with my endless requests. I also want to thank Jonathan Petherbridge at the London Bubble for making the archive available to me. A further thank you to Rosamond Castle for all her help. On a sadder note a posthumous thank you to the director Robert Hamlin. He responded to my email request for the information with warmth, humour and above all, great enthusiasm for the project. Also a posthumous thank you to the actor, Robert Demeger who was so very generous with the information regarding the production of Ninagawa’s Hamlet in which he played Polonius. Finally, a big thank you to John Ginman for all his help, patience and advice. 4 The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors During the Period 1960 to 2000. -

Ewan Maccoll, “The Brilliant Young Scots Dramatist”: Regional Myth-Making and Theatre Workshop

Ewan MacColl, “the brilliant young Scots dramatist”: Regional myth-making and Theatre Workshop Claire Warden, University of Lincoln Moving to London In 1952, Theatre Workshop had a decision to make. There was a growing sense that the company needed a permanent home (Goorney 1981: 85) and, rather than touring plays, to commit to a particular community. As they created their politically challenging, artistically vibrant work, group members sought a geographical stability, a chance to respond to and become part of a particular location. And, more than this, the group wanted a building to house them after many years of rented accommodation, draughty halls and borrowed rooms. Ewan MacColl and Joan Littlewood’s company had been founded in Manchester in 1945, aiming to create confrontational plays for the post-war audience. But the company actually had its origins in a number of pre-War Mancunian experiments. Beginning as the agit-prop Red Megaphones in 1931, MacColl and some local friends performed short sketches with songs, often discussing particularly Lancastrian issues, such as loom strikes and local unemployment. With the arrival of Littlewood, the group was transformed into, first, Theatre of Action (1934) and then Theatre Union (1936). Littlewood and MacColl collaborated well, with the former bringing some theatrical expertise from her brief spell at RADA (Holdsworth 2006: 45) (though, interestingly in light of the argument here, this experience largely taught Littlewood what she did not want in the theatre!) and the latter his experience of performing on the streets of Salford. Even in the early days of Theatre Workshop, as the company sought to create a formally innovative and thematically agitational theatre, the founders brought their own experiences of the Capital and the regions, of the centre and periphery. -

Topic Records 80Th Anniversary Start Time: 8Pm Running Time: 2 Hours 40 Minutes with Interval

Topic Records 80th Anniversary Start time: 8pm Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston discusses the history behind the world’s oldest independent label ahead of this collaborative performance. When Topic Records made its debut in 1939 with Paddy Ryan’s ‘The Man That Waters The Workers’ Beer’, an accordion-backed diatribe against capitalist businessmen who underpay their employees, it’s unlikely that anyone involved was thinking of the future – certainly not to 2019, when the label celebrates its 80th birthday. In any case, the future would have seemed very precarious in 1939, given the outbreak of World War II, during which Topic ceased most activity (shellac was particularly hard to source). But post-1945, the label made good on its original brief: ‘To use popular music to educate and inform and improve the lot of the working man,’ explains David Suff, the current spearhead of the world’s oldest independent label – and the undisputed home of British folk music. Tonight at the Barbican (where Topic held their 60th birthday concerts), musical director Eliza Carthy – part of the Topic recording family since 1997, though her parents Norma Waterson and Martin Carthy have been members since the sixties and seventies respectively - has marshalled a line-up to reflect the passing decades, which hasn’t been without its problems. ‘We have far too much material, given it’s meant to be a two-hour show!’ she says. ‘It’s impossible to represent 80 years – you’re talking about the left-wing leg, the archival leg, the many different facets of society - not just communists but farmers and factory workers - and the folk scene in the Fifties, the Sixties, the Seventies..