Vegetarianism and Veganism: Not Only Benefits but Also Gaps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Dairy and Plant Based Dairy Alternatives in Sustainable Diets

SLU Future Food – a research platform for a sustainable food system The role of dairy and plant based dairy alternatives in sustainable diets Future Food Reports 3 Elin Röös, Tara Garnett, Viktor Watz, Camilla Sjörs The role of dairy and plant based dairy alternatives in sustainable diets Elin Röös, Tara Garnett , Viktor Watz, Camilla Sjörs Publication: SLU Future Food Reports 3 Publisher: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, the research platform Future Food Publication year: 2018 Graphic form: Gunilla Leffler (cover) Photo: ombadesigns, Pixabay, CC0 Print: SLU Repro, Uppsala Paper: Scandia 2000 240 g (cover), Scandia 2000 130 g (insert) IBSN: 978-91-576-9604-5 Foreword Sustainable diets that are nutritionally adequate, environmentally sound, economically viable and socially and culturally acceptable are gaining increasing attention. The focus has long been on the role of meat and its association with high environmental pressures, especially greenhouse gas emissions, and its detrimental health effects at high consumption levels. Much less attention has been paid to the role of dairy products in sustainable diets. There is currently a rise in plant- based dairy alternatives, e.g. drinks, yogurt-like products, spreads, ice-cream etc. made of soy, legumes, seeds, nuts or cereals. These have potentially lower negative impacts than dairy products but different nutritional profiles, which raises concerns about their role as replacements or complements to dairy products in sustainable diets. These concerns form the background to this report. As a researcher at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Elin Röös) and director of the Food Climate Research Network (FCRN) (Tara Garnett), for some years we had spoken about a need to investigate dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives in diets more specifically and thoroughly. -

Eating a Low-Fiber Diet

Page 1 of 2 Eating a Low-fiber Diet What is fiber? Sample Menu Fiber is the part of food that the body cannot digest. Breakfast: It helps form stools (bowel movements). 1 scrambled egg 1 slice white toast with 1 teaspoon margarine If you eat less fiber, you may: ½ cup Cream of Wheat with sugar • Reduce belly pain, diarrhea (loose, watery stools) ½ cup milk and other digestive problems ½ cup pulp-free orange juice • Have fewer and smaller stools Snack: • Decrease inflammation (pain, redness and ½ cup canned fruit cocktail (in juice) swelling) in the GI (gastro-intestinal) tract 6 saltine crackers • Promote healing in the GI tract. Lunch: For a list of foods allowed in a low-fiber diet, see the Tuna sandwich on white bread back of this page. 1 cup cream of chicken soup ½ cup canned peaches (in light syrup) Why might I need a low-fiber diet? 1 cup lemonade You may need a low-fiber diet if you have: Snack: ½ cup cottage cheese • Inflamed bowels 1 medium apple, sliced and peeled • Crohn’s disease • Diverticular disease Dinner: 3 ounces well-cooked chicken breast • Ulcerative colitis 1 cup white rice • Radiation therapy to the belly area ½ cup cooked canned carrots • Chemotherapy 1 white dinner roll with 1 teaspoon margarine 1 slice angel food cake • An upcoming colonoscopy 1 cup herbal tea • Surgery on your intestines or in the belly area. For informational purposes only. Not to replace the advice of your health care provider. Copyright © 2007 Fairview Health Services. All rights reserved. Clinically reviewed by Shyamala Ganesh, Manager Clinical Nutrition. -

Derogatory Discourses of Veganism and the Reproduction of Speciesism in UK 1 National Newspapers Bjos 1348 134..152

The British Journal of Sociology 2011 Volume 62 Issue 1 Vegaphobia: derogatory discourses of veganism and the reproduction of speciesism in UK 1 national newspapers bjos_1348 134..152 Matthew Cole and Karen Morgan Abstract This paper critically examines discourses of veganism in UK national newspapers in 2007. In setting parameters for what can and cannot easily be discussed, domi- nant discourses also help frame understanding. Discourses relating to veganism are therefore presented as contravening commonsense, because they fall outside readily understood meat-eating discourses. Newspapers tend to discredit veganism through ridicule, or as being difficult or impossible to maintain in practice. Vegans are variously stereotyped as ascetics, faddists, sentimentalists, or in some cases, hostile extremists. The overall effect is of a derogatory portrayal of vegans and veganism that we interpret as ‘vegaphobia’. We interpret derogatory discourses of veganism in UK national newspapers as evidence of the cultural reproduction of speciesism, through which veganism is dissociated from its connection with debates concerning nonhuman animals’ rights or liberation. This is problematic in three, interrelated, respects. First, it empirically misrepresents the experience of veganism, and thereby marginalizes vegans. Second, it perpetuates a moral injury to omnivorous readers who are not presented with the opportunity to understand veganism and the challenge to speciesism that it contains. Third, and most seri- ously, it obscures and thereby reproduces -

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet a Family Resource from the Celiac Disease Program

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet A family resource from the Celiac Disease Program celiacdisease.stanfordchildrens.org What Is a Gluten-Free How Do I Diet? Get Started? A gluten-free diet is a diet that completely Your first instinct may be to stop at the excludes the protein gluten. Gluten is grocery store on your way home from made up of gliadin and glutelin which is the doctor’s office and search for all the found in grains including wheat, barley, gluten-free products you can find. While and rye. Gluten is found in any food or this initial fear may feel a bit overwhelming product made from these grains. These but the good news is you most likely gluten-containing grains are also frequently already have some gluten-free foods in used as fillers and flavoring agents and your pantry. are added to many processed foods, so it is critical to read the ingredient list on all food labels. Manufacturers often Use this guide to select appropriate meals change the ingredients in processed and snacks. Prepare your own gluten-free foods, so be sure to check the ingredient foods and stock your pantry. Many of your list every time you purchase a product. favorite brands may already be gluten-free. The FDA announced on August 2, 2013, that if a product bears the label “gluten-free,” the food must contain less than 20 ppm gluten, as well as meet other criteria. *The rule also applies to products labeled “no gluten,” “free of gluten,” and “without gluten.” The labeling of food products as “gluten- free” is a voluntary action for manufacturers. -

Plant-Based Milk Alternatives

Behind the hype: Plant-based milk alternatives Why is this an issue? Health concerns, sustainability and changing diets are some of the reasons people are choosing plant-based alternatives to cow’s milk. This rise in popularity has led to an increased range of milk alternatives becoming available. Generally, these alternatives contain less nutrients than cow’s milk. In particular, cow’s milk is an important source of calcium, which is essential for growth and development of strong bones and teeth. The nutritional content of plant-based milks is an important consideration when replacing cow’s milk in the diet, especially for young children under two-years-old, who have high nutrition needs. What are plant-based Table 1: Some Nutrients in milk alternatives? cow’s milk and plant-based Plant-based milk alternatives include legume milk alternatives (soy milk), nut (almond, cashew, coconut, macadamia) and cereal-based (rice, oat). Other ingredients can include vegetable oils, sugar, and thickening ingredients Milk type Energy Protein Calcium kJ/100ml g/100ml mg/100ml such as gums, emulsifiers and flavouring. Homogenised cow’s milk 263 3.3 120 How are plant-based milk Legume alternatives nutritionally Soy milk 235-270 3.0-3.5 120-160* different to cow’s milk? Nut Almond milk 65-160 0.4-0.7 75-120* Plant-based milk alternatives contain less protein and Cashew milk 70 0.4 120* energy. Unfortified versions also contain very little calcium, B vitamins (including B12) and vitamin D Coconut milk** 95-100 0.2 75-120* compared to cow’s milk. -

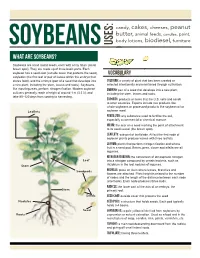

What Are Soybeans?

candy, cakes, cheeses, peanut butter, animal feeds, candles, paint, body lotions, biodiesel, furniture soybeans USES: What are soybeans? Soybeans are small round seeds, each with a tiny hilum (small brown spot). They are made up of three basic parts. Each soybean has a seed coat (outside cover that protects the seed), VOCABULARY cotyledon (the first leaf or pair of leaves within the embryo that stores food), and the embryo (part of a seed that develops into Cultivar: a variety of plant that has been created or a new plant, including the stem, leaves and roots). Soybeans, selected intentionally and maintained through cultivation. like most legumes, perform nitrogen fixation. Modern soybean Embryo: part of a seed that develops into a new plant, cultivars generally reach a height of around 1 m (3.3 ft), and including the stem, leaves and roots. take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. Exports: products or items that the U.S. sells and sends to other countries. Exports include raw products like whole soybeans or processed products like soybean oil or Leaflets soybean meal. Fertilizer: any substance used to fertilize the soil, especially a commercial or chemical manure. Hilum: the scar on a seed marking the point of attachment to its seed vessel (the brown spot). Leaflets: sub-part of leaf blade. All but the first node of soybean plants produce leaves with three leaflets. Legume: plants that perform nitrogen fixation and whose fruit is a seed pod. Beans, peas, clover and alfalfa are all legumes. Nitrogen Fixation: the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen Leaf into a nitrogen compound by certain bacteria, such as Stem rhizobium in the root nodules of legumes. -

219 No Animal Food

219 No Animal Food: The Road to Veganism in Britain, 1909-1944 Leah Leneman1 UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH There were individuals in the vegetarian movement in Britain who believed that to refrain from eating flesh, fowl, and fish while continuing to partake of dairy products and eggs was not going far enough. Between 1909 and 1912, The Vegetarian Society's journal published a vigorous correspond- ence on this subject. In 1910, a publisher brought out a cookery book entitled, No Animal Food. After World War I, the debate continued within the Vegetarian Society about the acceptability of animal by-products. It centered on issues of cruelty and health as well as on consistency versus expediency. The Society saw its function as one of persuading as many people as possible to give up slaughterhouse products and also refused journal space to those who abjured dairy products. The year 1944 saw the word "vergan" coined and the breakaway Vegan Society formed. The idea that eating animal flesh is unhealthy and morally wrong has been around for millennia, in many different parts of the world and in many cultures (Williams, 1896). In Britain, a national Vegetarian Society was formed in 1847 to promulgate the ideology of non-meat eating (Twigg, 1982). Vegetarianism, as defined by the Society-then and now-and by British vegetarians in general, permitted the consumption of dairy products and eggs on the grounds that it was not necessary to kill the animal to obtain them. In 1944, a group of Vegetarian Society members coined a new word-vegan-for those who refused to partake of any animal product and broke away to form a separate organization, The Vegan Society. -

Vegetarianism and World Peace and Justice

Visit the Triangle-Wide calendar of peace events, www.trianglevegsociety.org/peacecalendar VVeeggeettaarriiaanniissmm,, WWoorrlldd PPeeaaccee,, aanndd JJuussttiiccee By moving toward vegetarianism, can we help avoid some of the reasons for fighting? We find ourselves in a world of conflict and war. Why do people fight? Some conflict is driven by a desire to impose a value system, some by intolerance, and some by pure greed and quest for power. The struggle to obtain resources to support life is another important source of conflict; all creatures have a drive to live and sustain themselves. In 1980, Richard J. Barnet, director of the Institute for Policy Studies, warned that by the end of the 20th century, anger and despair of hungry people could lead to terrorist acts and economic class war [Staten Island Advance, Susan Fogy, July 14, 1980, p.1]. Developed nations are the largest polluters in the world; according to Mother Jones (March/April 1997, http://www. motherjones.com/mother_jones/MA97/hawken2.html), for example, Americans, “have the largest material requirements in the world ... each directly or indirectly [using] an average of 125 pounds of material every day ... Americans waste more than 1 million pounds per person per year ... less than 5 percent of the total waste ... gets recycled”. In the US, we make up 6% of the world's population, but consume 30% of its resources [http://www.enough.org.uk/enough02.htm]. Relatively affluent countries are 15% of the world’s population, but consume 73% of the world’s output, while 78% of the world, in developing nations, consume 16% of the output [The New Field Guide to the U. -

Negotiating Gender and Spirituality in Literary Representations of Rastafari

Negotiating Gender and Spirituality in Literary Representations of Rastafari Annika McPherson Abstract: While the male focus of early literary representations of Rastafari tends to emphasize the movement’s emergence, goals or specific religious practices, more recent depictions of Rasta women in narrative fiction raise important questions not only regarding the discussion of gender relations in Rastafari, but also regarding the functions of literary representations of the movement. This article outlines a dialogical ‘reasoning’ between the different negotiations of gender in novels with Rastafarian protagonists and suggests that the characters’ individual spiritual journeys are key to understanding these negotiations within the gender framework of Rastafarian decolonial practices. Male-centred Literary Representations of Rastafari Since the 1970s, especially, ‘roots’ reggae and ‘dub’ or performance poetry have frequently been discussed as to their relations to the Rastafari movement – not only based on their lyrical content, but often by reference to the artists or poets themselves. Compared to these genres, the representation of Rastafari in narrative fiction has received less attention to date. Furthermore, such references often appear to serve rather descriptive functions, e.g. as to the movement’s philosophy or linguistic practices. The early depiction of Rastafari in Roger Mais’s “morality play” Brother Man (1954), for example, has been noted for its favourable representation of the movement in comparison to the press coverage of -

Scientific Evidence of Diets for Weight Loss

Nutrition 69 (2020) 110549 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Nutrition journal homepage: www.nutritionjrnl.com Scientific evidence of diets for weight loss: Different macronutrient composition, intermittent fasting, and popular diets Rachel Freire Ph.D. * Mucosal Immunology and Biology Research Center and Center for Celiac Research and Treatment, Department of Pediatrics, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: New dietary strategies have been created to treat overweight and obesity and have become popular and widely adopted. Nonetheless, they are mainly based on personal impressions and reports published in books and magazines, rather than on scientific evidence. Animal models and human clinical trials have been Keywords: employed to study changes in body composition and metabolic outcomes to determine the most effective Obesity diet. However, the studies present many limitations and should be carefully analyzed. The aim of this review Weight-loss was to discuss the scientific evidence of three categories of diets for weight loss. There is no one most effec- Popular diets tive diet to promote weight loss. In the short term, high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets and intermittent Fasting Macronutrient fasting are suggested to promote greater weight loss and could be adopted as a jumpstart. However, owing to adverse effects, caution is required. In the long term, current evidence indicates that different diets pro- moted similar weight loss and adherence to diets will predict their success. Finally, it is fundamental to adopt a diet that creates a negative energy balance and focuses on good food quality to promote health. © 2019 Elsevier Inc. -

Relation Between a Health-Conscious Diet and Blood Lipids

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2001) 55, 887–895 ß 2001 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0954–3007/01 $15.00 www.nature.com/ejcn Original Communication Giessen Wholesome Nutrition Study: relation between a health-conscious diet and blood lipids I Hoffmann1,2*, MJ Groeneveld1, H Boeing3, C Koebnick4, S Golf 5, N Katz5 and C Leitzmann1 1Institute of Nutrition Science, University of Giessen, Germany; 2National Research Centre for Nutrition, Karlsruhe, Germany; 3German Institute for Nutrition Research, Potsdam-Rehbru¨cke, Germany; 4Department of Medical Informatics, Biometry and Epidemiology, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany; and 5Institute of Clinical Chemistry, Department of Medicine, University of Giessen, Germany Objective: To study in humans the relationship between a diet consistent with most of the current recommenda- tions for the prevention of nutrition-related diseases (Wholesome Nutrition) and the blood lipid profile (total cholesterol, LDL-, HDL-cholesterol, LDL=HDL-ratio, triglycerides). Design: Cross-sectional study with two diet groups. Setting: Former West Germany. Subjects: Healthy women (n ¼ 243, aged 25 – 65 y) adhering to Wholesome Nutrition for at least 5 y (subdivided into 111 ovo-lacto vegetarians and 132 low-meat eaters) and an according control group of 175 women eating an average German mixed diet. They were all recruited through an advertisement campaign and selected on the basis of their food consumption. Results: Considering potential confounders, the Wholesome Nutrition subgroups had higher HDL-cholesterol levels than the control group. No differences were observed for total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol. For LDL=HDL-ratio and triglycerides the effect of diet was dependent on interaction terms. -

Vegetarian Journal's 25Th Anniversary Issue

Cruelty-Free Businesses Still Going Strong Today 3 O N , I V X X E M U L O V VEGETARIAN J O U R N A L HEALTH ECOLOGY ETHICS What Do Longtime Happy Silver Leaders of the Anniversary, Vegetarian Movement Think the Next 25 Years VRG! Colossal Chocolate Cake with Will Bring? Chocolate Ganache (page 32) $4.50 USA/$5.50 CANADA g r o . 25 Wonderful g r v . w w w Vegan Cuisines! NUTRITION HOTLINE QUESTION: “My 10-year-old grand- In addition, your daughter might REED MANGELS, PhD, RD daughter has decided to become a like some resources on vegetarian- vegetarian. My daughter says she ism. VRG’s website has a section doesn’t know what to feed her and on vegetarian children and teens. says she is mainly eating cheese and Your granddaughter and her par- now is not eating veggies or fruits. ents may find it helpful to meet My granddaughter keeps saying with a dietitian who is knowledge- she is hungry all the time.” able about vegetarian diets and A.V., via e-mail can do nutrition education while helping them develop meal ideas. ANSWER: Here are some sugges- tions you may want to pass on QUESTION: “I was wondering if to your daughter. It’s important my being a vegan would affect the for your granddaughter to be health of my daughter who is 11 aware that it’s her responsibility months old and is still nursing. (with the help of her parents) to She is on the small side, but I am choose a variety of healthy vege- only 4' 10".