UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welsh Tribal Law and Custom in the Middle Ages

THOMAS PETER ELLIS WELSH TRIBAL LAW AND CUSTOM IN THE MIDDLE AGES IN 2 VOLUMES VOLUME I1 CONTENTS VOLUME I1 p.1~~V. THE LAWOF CIVILOBLIGATIONS . I. The Formalities of Bargaining . .a . 11. The Subject-matter of Agreements . 111. Responsibility for Acts of Animals . IV. Miscellaneous Provisions . V. The Game Laws \TI. Co-tillage . PARTVI. THE LAWOF CRIMESAND TORTS. I. Introductory . 11. The Law of Punishtnent . 111. ' Saraad ' or Insult . 1V. ' Galanas ' or Homicide . V. Theft and Surreption . VI. Fire or Arson . VII. The Law of Accessories . VIII. Other Offences . IX. Prevention of Crime . PARTVIl. THE COURTSAND JUDICIARY . I. Introductory . 11. The Ecclesiastical Courts . 111. The Courts of the ' Maerdref ' and the ' Cymwd ' IV. The Royal Supreme Court . V. The Raith of Country . VI. Courts in Early English Law and in Roman Law VII. The Training and Remuneration of Judges . VIII. The Challenge of Judges . IX. Advocacy . vi CONTENTS PARTVIII. PRE-CURIALSURVIVALS . 237 I. The Law of Distress in Ireland . 239 11. The Law of Distress in Wales . 245 111. The Law of Distress in the Germanic and other Codes 257 IV. The Law of Boundaries . 260 PARTIX. THE L4w OF PROCEDURE. 267 I. The Enforcement of Jurisdiction . 269 11. The Law of Proof. Raith and Evideilce . , 301 111. The Law of Pleadings 339 IV. Judgement and Execution . 407 PARTX. PART V Appendices I to XI11 . 415 Glossary of Welsh Terms . 436 THE LAW OF CIVIL OBLIGATIONS THE FORMALITIES OF BARGAINING I. Ilztroductory. 8 I. The Welsh Law of bargaining, using the word bargain- ing in a wide sense to cover all transactions of a civil nature whereby one person entered into an undertaking with another, can be considered in two aspects, the one dealing with the form in which bargains were entered into, or to use the Welsh term, the ' bond of bargain ' forming the nexus between the parties to it, the other dealing with the nature of the bargain entered int0.l $2. -

Welsh Government Summary of Events Following The

Public Accounts Committee - Additional Written Evidence Summary of events following the Statutory Inquiry at Tai Cantref The Statutory Inquiry report was completed in October 2015. The report found multiple instances of mismanagement and misconduct. The report made no comment beyond its brief to establish whether there was evidence to support the serious allegations made by whistle blowers. It made no recommendations or commentary on possible ways forward. Tai Cantref’s Board were given until 13th November 2015 to set out a credible response and plan to deal with the findings of the inquiry. The Welsh Government Regulation Team (the Regulator) considered that the initial response was inadequate in both the association’s acceptance of the findings and its intentions and commitment to tackling the issues raised. The Board was also required to share a copy of the Inquiry with its lenders who were similarly concerned with the response and reserved the right to enforce loan conditions. By this point an event of default had been triggered in Tai Cantref’s loan agreements. Following detailed discussions, including with lenders, the Board was given a second chance to respond to the findings. Shortly after this decision was notified to Tai Cantref, the Chair resigned and an existing Board member was unanimously appointed as the new Chair. The Board then took a number of key decisions which provided assurance it was now seeking to respond to the findings: the Board appointed a consultant to provide immediate support the Board to address the Inquiry findings. three suitably experienced, first language welsh speakers, were co- opted to strengthen the Board. -

The Reform Treatises and Discourse of Early Tudor Ireland, C

The Reform Treatises and Discourse of Early Tudor Ireland, c. 1515‐1541 by Chad T. Marshall BA (Hons., Archaeology, Toronto), MA (History and Classics, Tasmania) School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, December, 2018 Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Signed: _________________________ Date: 7/12/2018 i Authority of Access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: _________________________ Date: 7/12/2018 ii Acknowledgements This thesis is for my wife, Elizabeth van der Geest, a woman of boundless beauty, talent, and mystery, who continuously demonstrates an inestimable ability to elevate the spirit, of which an equal part is given over to mastery of that other vital craft which serves to refine its expression. I extend particular gratitude to my supervisors: Drs. Gavin Daly and Michael Bennett. They permitted me the scope to explore the arena of Late Medieval and Early Modern Ireland and England, and skilfully trained wide‐ranging interests onto a workable topic and – testifying to their miraculous abilities – a completed thesis. Thanks, too, to Peter Crooks of Trinity College Dublin and David Heffernan of Queen’s University Belfast for early advice. -

Translating Risk Assessment to Contingency Planning for CO2 Geologic Storage: a Methodological Framework

Translating Risk Assessment to Contingency Planning for CO2 Geologic Storage: A Methodological Framework Authors Karim Farhat a and Sally M. Benson b a Department of Management Science and Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA b Department of Energy Resources Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA Contact Information Karim Farhat: [email protected] Sally M. Benson: [email protected] Corresponding Author Karim Farhat 475 Via Ortega Huang Engineering Center, 245A Stanford, CA 94305, USA Email: [email protected] Tel: +1-650-644-7451 May 2016 1 Abstract In order to ensure safe and effective long-term geologic storage of carbon dioxide (CO2), existing regulations require both assessing leakage risks and responding to leakage incidents through corrective measures. However, until now, these two pieces of risk management have been usually addressed separately. This study proposes a methodological framework that bridges risk assessment to corrective measures through clear and collaborative contingency planning. We achieve this goal in three consecutive steps. First, a probabilistic risk assessment (PRA) approach is adopted to characterize potential leakage features, events and processes (FEP) in a Bayesian events tree (BET), resulting in a risk assessment matrix (RAM). The RAM depicts a mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive set of leakage scenarios with quantified likelihood, impact, and tolerance levels. Second, the risk assessment matrix is translated to a contingency planning matrix (CPM) that incorporates a tiered- contingency system for risk-preparedness and incident-response. The leakage likelihood and impact dimensions of RAM are translated to resource proximity and variety dimensions in CPM, respectively. To ensure both rapid and thorough contingency planning, more likely or frequent risks require more proximate resources while more impactful risks require more various resources. -

IV. the Cantrefs of Morgannwg

; THE TRIBAL DIVISIONS OF WALES, 273 Garth Bryngi is Dewi's honourable hill, CHAP. And Trallwng Cynfyn above the meadows VIII. Llanfaes the lofty—no breath of war shall touch it, No host shall disturb the churchmen of Llywel.^si It may not be amiss to recall the fact that these posses- sions of St. David's brought here in the twelfth century, to re- side at Llandduw as Archdeacon of Brecon, a scholar of Penfro who did much to preserve for future ages the traditions of his adopted country. Giraldus will not admit the claim of any region in Wales to rival his beloved Dyfed, but he is nevertheless hearty in his commendation of the sheltered vales, the teeming rivers and the well-stocked pastures of Brycheiniog.^^^ IV. The Cantrefs of Morgannwg. The well-sunned plains which, from the mouth of the Tawe to that of the Wye, skirt the northern shore of the Bristol Channel enjoy a mild and genial climate and have from the earliest times been the seat of important settlements. Roman civilisation gained a firm foothold in the district, as may be seen from its remains at Cardiff, Caerleon and Caerwent. Monastic centres of the first rank were established here, at Llanilltud, Llancarfan and Llandaff, during the age of early Christian en- thusiasm. Politically, too, the region stood apart from the rest of South Wales, in virtue, it may be, of the strength of the old Silurian traditions, and it maintained, through many vicissitudes, its independence under its own princes until the eve of the Norman Conquest. -

2017 Ram 1500/2500/3500 Truck Owner's Manual

2017 RAM TRUCK 1500/2500/3500 STICK WITH THE SPECIALISTS® RAM TRUCK 2017 1500/2500/3500 OWNER’S MANUAL 17D241-126-AD ©2016 FCA US LLC. All Rights Reserved. fourth Edition Ram is a registered trademark of FCA US LLC. Printed in U.S.A. VEHICLES SOLD IN CANADA This manual illustrates and describes the operation of With respect to any Vehicles Sold in Canada, the name FCA features and equipment that are either standard or op- US LLC shall be deemed to be deleted and the name FCA tional on this vehicle. This manual may also include a Canada Inc. used in substitution therefore. description of features and equipment that are no longer DRIVING AND ALCOHOL available or were not ordered on this vehicle. Please Drunken driving is one of the most frequent causes of disregard any features and equipment described in this accidents. manual that are not on this vehicle. Your driving ability can be seriously impaired with blood FCA US LLC reserves the right to make changes in design alcohol levels far below the legal minimum. If you are and specifications, and/or make additions to or improve- drinking, don’t drive. Ride with a designated non- ments to its products without imposing any obligation drinking driver, call a cab, a friend, or use public trans- upon itself to install them on products previously manu- portation. factured. WARNING! Driving after drinking can lead to an accident. Your perceptions are less sharp, your reflexes are slower, and your judgment is impaired when you have been drinking. Never drink and then drive. -

Superman(Jjabrams).Pdf

L, July 26, 2002 SUPERMAN FADE IN: . .. INT. TV MONITOR - DAY TIGHT ON a video image of a news telecast. Ex ~t th efs no one there -- just the empty newsdesk. Odd. e Suddenly a NEWSCASTER appears behind the desk - rushed and unkempt. Fumbles with his clip mic trembling. It's unsettling; be looks up at us, desperately to sound confident. But his voice Nm?!3CASTER Ladies and gentlen. If you are watching this, and are taking shelter underground, we strongly urg you -- all of vou -- to do so immediately. Anywhere-- anywhere e are, anywhere you can find. (beat) At this hour, all we know is that there are visitors on this planet-- and that there's a conflict between 'v them-- the Giza Pyramids have been @ destroyed-- sections of Paris. Massive fires are raging from Venezuela to Chile-- a great deal of Seoul, Korea ... no longer exists ... All this man wants to-do is cry. But he's a realize now that werite been SLOWLY PUSHING IN NEWSCASTER ( con t ' d ) Only weeks ago this report would've seemed.. ludicrous. Aliens.. usi Earth as a battleground. .. ( then, with growing venom: ) ... but that was before Superman. (beat1 It turns out that our faith was naive. Premature. Perhaps, given Y the state pf the world. .- simply desperate-- .. , Something urgent is YELLED from behind the c Newscaster looks off, ' fied -- he yells but it's masked by a SHATT!L'RING -- FLYING GLASS -- the video . .. camera SHAKES -- . -.~. &+,. 9' .. .-. .. .. .: . .I _ - - . - .. ( CONTINUED) . 2. CONTINUED: 4 -. A TERRIBLE WHI.STLE, then an EXPIX)SION -- '1 WHIPPED OUT OF FRAME in the same horrible inst . -

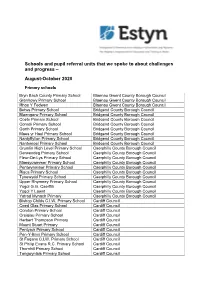

Schools and Pupil Referral Units That We Spoke to Autumn Term 2020

Schools and pupil referral units that we spoke to about challenges and progress – August-October 2020 Primary schools Bryn Bach County Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Glanhowy Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Rhos Y Fedwen Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Betws Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Blaengarw Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Coety Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Corneli Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Garth Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Maes yr Haul Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Nantyffyllon Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Nantymoel Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Crumlin High Level Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Derwendeg Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Fleur-De-Lys Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Maesycwmmer Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Pentwynmawr Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Risca Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Tynewydd Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Upper Rhymney Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Ysgol G.G. Caerffili Caerphilly County Borough Council Ysgol Y Lawnt Caerphilly County Borough Council Ystrad Mynach Primary Caerphilly County Borough Council Bishop Childs C.I.W. Primary School Cardiff Council Coed Glas Primary School Cardiff Council Coryton Primary School Cardiff Council Creigiau Primary School Cardiff Council Herbert Thompson Primary Cardiff Council Mount Stuart Primary Cardiff Council Pentyrch Primary School Cardiff Council Pen-Y-Bryn Primary School Cardiff Council St Fagans C.I.W. Primary School Cardiff Council St Philip Evans R.C. Primary School Cardiff Council Thornhill Primary School Cardiff Council Tongwynlais Primary School Cardiff Council Ysgol Gymraeg Treganna Cardiff Council Ysgol-Y-Wern Cardiff Council Brynamman Primary School Carmarthenshire County Council Cefneithin C.P. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

Schools and Pupil Referral Units That We Spoke to September

Schools and pupil referral units that we spoke to about challenges and progress – August-December 2020 Primary schools All Saints R.C. Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Blaen-Y-Cwm C.P. School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Bryn Bach County Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Coed -y- Garn Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Deighton Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Glanhowy Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Rhos Y Fedwen Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Sofrydd C.P. School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council St Illtyd's Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council St Mary's Roman Catholic - Brynmawr Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Willowtown Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Ysgol Bro Helyg Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Ystruth Primary Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Afon-Y-Felin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Archdeacon John Lewis Bridgend County Borough Council Betws Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Blaengarw Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Brackla Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Bryncethin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Bryntirion Infants School Bridgend County Borough Council Cefn Glas Infant School Bridgend County Borough Council Coety Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Corneli Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Cwmfelin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Garth Primary School Bridgend -

Concealed Criticism: the Uses of History in Anglonorman Literature

Concealed Criticism: The Uses of History in AngloNorman Literature, 11301210 By William Ristow Submitted to The Faculty of Haverford College In partial fulfillment of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History 22 April, 2016 Readers: Professor Linda Gerstein Professor Darin Hayton Professor Andrew Friedman Abstract The twelfth century in western Europe was marked by tensions and negotiations between Church, aristocracy, and monarchies, each of which vied with the others for power and influence. At the same time, a developing literary culture discovered new ways to provide social commentary, including commentary on the power-negotiations among the ruling elite. This thesis examines the the functions of history in four works by authors writing in England and Normandy during the twelfth century to argue that historians used their work as commentary on the policies of Kings Stephen, Henry II, and John between 1130 and 1210. The four works, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, Master Wace’s Roman de Brut, John of Salisbury’s Policraticus, and Gerald of Wales’ Expugnatio Hibernica, each use descriptions of the past to criticize the monarchy by implying that the reigning king is not as good as rulers from history. Three of these works, the Historia, the Roman, and the Expugnatio, take the form of narrative histories of a variety of subjects both imaginary and within the author’s living memory, while the fourth, the Policraticus, is a guidebook for princes that uses historical examples to prove the truth of its points. By examining the way that the authors, despite the differences between their works, all use the past to condemn royal policies by implication, this thesis will argue that Anglo-Norman writers in the twelfth century found history-writing a means to criticize reigning kings without facing royal retribution. -

But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us: Ireland, Colonialism, and Renaissance Literature

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, British Isles English Language and Literature 1999 But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us: Ireland, Colonialism, and Renaissance Literature Andrew Murphy University of St. Andrews Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Murphy, Andrew, "But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us: Ireland, Colonialism, and Renaissance Literature" (1999). Literature in English, British Isles. 16. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_british_isles/16 Irish Literature, History, & Culture Jonathan Allison, General Editor Advisory Board George Bornstein, University of Michigan Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, University of Texas James S. Donnelly Jr., University of Wisconsin Marianne Elliott, University of Liverpool Roy Foster, Hertford College, Oxford David Lloyd, University of California, Berkeley Weldon Thornton, University of North Carolina This page intentionally left blank But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us Ireland, Colonialisn1, and Renaissance Literature Andrew Murphy THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1999 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.