Ethnography of Tribes in India 1. Geographical Distribution of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ngos Registered in the State of Assam 2012-13.Pdf

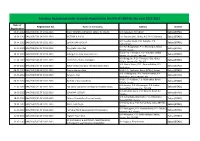

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2012-2013 Date of Registration No. Name of the Society Address District Registration 09-04-2012 BAK/260/E/01 OF 2012-2013 JEUTY GRAMYA UNNAYAN SAMITTEE (JGUS) Vill. Batiamari, PO Kalbari Baksa (BTAD) 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/02 OF 2012-2013 VICTORY-X N.G.O. H.O. Barama (Niz-Juluki), P.O. & P.S. Barama Baksa (BTAD) Vill. Katajhar Gaon, P.O. Katajhar, P.S. 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/03 OF 2012-2013 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Baksa (BTAD) Gobardhana Vill.-Pub Bangnabari, P.O.-Mushalpur, Baksa 11-04-2012 BAK/260/E/04 OF 2012-2013 Daugaphu Aiju Afad Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. Vill. & P.O.-Tamulpur, P.S.-Tamulpur, Baksa 24-04-2012 BAK/260/E/05 OF 2012-2013 Udangshree Jana Sewa Samittee Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367 Vill.-Baregaon, P.O.- Tamulpur, Dist.-Baksa 27-04-2012 BAK/260/E/06 OF 2012-2013 RamDhenu N.g.o., Baregaon Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367. Vill.-Natun Sripur, P.O.- Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/07 OF 2012-2013 Natun Sripur (Sonapur /Khristan Basti) Baro Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/08 OF 2012-2013 Dodere Harimu Afat Vill.& P.O.-Laukhata, Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Baksa (BTAD) Vill.-Goldingpara, P.O.-Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/09 OF 2012-2013 Jwngma Afat Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, Baksa (BTAD), Ass. Vill.& P.O.-Adalbari, P.S.-Mushalpur, Baksa 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/10 OF 2012-2013 Barhukha Sport Academy Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. -

2001 Asia Harvest Newsletters

Asia Harvest Swing the Sickle for the Harvest is Ripe! (Joel 3:13) Box 17 - Chang Klan P.O. - Chiang Mai 50101 - THAILAND Tel: (66-53) 801-487 Fax: (66-53) 800-665 Email: [email protected] Web: www.antioch.com.sg/mission/asianmo April 2001 - Newsletter #61 China’s Neglected Minorities Asia Harvest 2 May 2001 FrFromom thethe FrFrontont LinesLines with Paul and Joy In the last issue of our newsletter we introduced you to our new name, Asia Harvest. This issue we introduce you to our new style of newsletter. We believe a large part of our ministry is to profile and present unreached people groups to Christians around the world. Thanks to the Lord, we have seen and heard of thousands of Christians praying for these needy groups, and efforts have been made by many ministries to take the Gospel to those who have never heard it before. Often we handed to our printer excellent and visually powerful color pictures of minority people, only to be disappointed when the completed newsletter came back in black and white, losing the impact it had in color. A few months ago we asked our printer, just out of curiosity, how much more it would cost if our newsletter was all in full color. We were shocked to find the differences were minimal! In fact, it costs just a few cents more to print in color than in black and white! For this reason we plan to produce our newsletters in color. Hopefully the visual difference will help generate even more prayer and interest in the unreached peoples of Asia! Please look through the pictures in this issue and see the differ- ence color makes. -

Download PDF (63.9

Index Abbott, Tony 350 National Reorganization Process Abdülhamid II 121 (1976–83) 259 accountability 41, 52, 235, 265, 333, public sector of 259–60 338, 451 Aristotle 110 collective 82 Asian Financial Crisis (1997–9) 342 democratic 106 Association of Education Committees mechanisms 173 68 political 81, 93 Australia 4, 7, 17, 25, 96, 337, 341–2, shared 333 351, 365 webs of 81, 88, 93, 452 Australian Capital Territory 361 administrative management principles Australian National Audit Office planning, organizing, staffing, (ANAO) 333, 350 directing, coordinating, Australian Public Service reporting and budgeting Commission (APSC) 328–9, (POSDCORB) 211 336 Afghanistan 445–6 Changing Behaviour (2007) Operation Enduring Freedom 346–7 (2001–14) 69, 200, 221, 443 Tackling Wicked Problems (2007) presence of private military 347 contractors during 209 Australian Taxation Office (ATO) African National Congress (ANC) 5, 334 138, 141 Centrelink 335, 338 Cadre Policy and Deployment closure of 330–31 Strategy (1997) 141 Council of Australian Governments Albania 122 (COAG) 344–5, 352 Alfonsín, Raúl Closing the Gap program 355–8, administration of 259–60 365 electoral victory of (1983) 259 National Indigenous Reform Algeria 177–8 Agreement (NIRA) (2008) Andrews, Matt 107 355–7 Appleby, Paul 272 Reform Council 357, 365 Report for Government of India trials (2002) 352–4 (1953) 276 Department of Education, Argentina 6, 251, 262 Employment and Workplace bureaucracy of 259–60, 262–3 Relations (DEEWR) 335 democratic reform in 259 Department of Families, Housing, -

GOVERNMENT of ASSAM (Report No

STATE FINANCES AUDIT REPORT OF THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL OF INDIA FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2019 GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM (Report No. 1 of 2020) Table of Contents Paragraph No. Page No. Preface -- v Executive Summary -- vii Chapter 1: Overview Profile of the State 1.1 1 Basis and Approach to State Finances Audit Report 1.2 1 Report Structure 1.3 2 Structure of Government Accounts 1.4 3 Budgetary Processes 1.5 4 Gross State Domestic Product of Assam 1.6 5 Trends in Key Fiscal Parameters 1.7 7 What are Deficit and Surplus? 1.7.1 8 Trend of Deficit/Surplus 1.7.2 8 Components of Fiscal Deficit and its Financing Pattern 1.7.3 9 Actual Revenue and Fiscal Deficit 1.7.4 10 Fiscal Correction Path 1.8 10 AFRBM Targets on Key Fiscal Parameters and 1.8.1 11 Achievements thereon Medium Term Fiscal Plan 1.8.2 12 Chapter 2: Finances of the State Introduction 2.1 13 Major Changes in Key Fiscal Aggregates during 2018-19 2.2 13 vis-à-vis 2017-18 Sources and Application of Funds 2.3 13 Resources of the State 2.4 14 Revenue Receipts 2.5 15 Trends and Growth of Revenue Receipts 2.5.1 15 State’s Own Resources 2.5.2 17 Own Tax Revenue 2.5.2.1 17 State Goods and Services Tax (SGST) 2.5.2.2 18 Non-Tax Revenue 2.5.2.3 19 Central Tax Transfers 2.5.2.4 20 Grants-in-Aid from Government of India 2.5.2.5 20 Fourteenth Finance Commission Grants 2.5.2.6 21 Funds Transferred to Implementing Agencies Outside the 2.5.2.7 21 State Budget Capital Receipts 2.6 22 Application of Resources 2.7 23 Revenue Expenditure 2.7.1 25 Major Changes in Revenue Expenditure 2.7.1.1 26 Object Head-wise Expenditure 2.7.2 27 Committed Expenditure 2.7.3 27 Salaries and Wages 2.7.3.1 28 Interest Payments 2.7.3.2 29 Pensions 2.7.3.3 29 Table of Contents Table of Contents Paragraph No. -

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India Vani K. Borooah, Amaresh Dubey and Sriya Iyer ABSTRACT This article investigates the effect of jobs reservation on improving the eco- nomic opportunities of persons belonging to India’s Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST). Using employment data from the 55th NSS round, the authors estimate the probabilities of different social groups in India being in one of three categories of economic status: own account workers; regu- lar salaried or wage workers; casual wage labourers. These probabilities are then used to decompose the difference between a group X and forward caste Hindus in the proportions of their members in regular salaried or wage em- ployment. This decomposition allows us to distinguish between two forms of difference between group X and forward caste Hindus: ‘attribute’ differences and ‘coefficient’ differences. The authors measure the effects of positive dis- crimination in raising the proportions of ST/SC persons in regular salaried employment, and the discriminatory bias against Muslims who do not benefit from such policies. They conclude that the boost provided by jobs reservation policies was around 5 percentage points. They also conclude that an alterna- tive and more effective way of raising the proportion of men from the SC/ST groups in regular salaried or wage employment would be to improve their employment-related attributes. INTRODUCTION In response to the burden of social stigma and economic backwardness borne by persons belonging to some of India’s castes, the Constitution of India allows for special provisions for members of these castes. -

A Study on Socio-Cultural Function of the Deori Community

GLOBUS Journal of Progressive Education A Refereed Research Journal Vol 4 / No 1 / Jan-Jun 2014 ISSN: 2231-1335 A STUDY ON SOCIO-CULTURAL FUNCTION OF THE DEORI COMMUNITY Palash Dutta* Introduction Social customs and traditions play a vital role in the needs of the market will be the focal point of any cultural life of an ethnic group. There are customs development effort. On the social aspect of and traditions with core values which a tradition development, the main focus would be to create an bound society can afford to do away with even under enabling environment for realization of total human the most adverse situations. But the customs and potential with equal opportunities for all. Because of traditions with superficial or periphery values are their interrelation, the development efforts need to be always subjects to change since they can hardly stand grouped under the following major groups. the rapid changes specially brought about by modern A. Agricultural and allied sector. scientific advancement. Insight knowledge of the B. Social Welfare sector. social customs and traditions having core values of C. Infrastructure sector. an ethnic group is a must for administrators as well as D. Industry and commerce sector. developmental personnel working in the tribal areas. E. Essential services sector. Such knowledge is very much helpful to researchers and others with an inquisitive mind. Development of Deori Autonomous Council came into being as a Deoris economically and socially, lies in the growth result of an agreement signed among the Deoris and of the economy in the Agriculture and allied sectors. -

Tribes in India 208 Reading

Department of Social Work Indira Gandhi National Tribal University Regional Campus Manipur Name of The Paper: Tribal Development (218) Semester: IV Course Faculty: Ajeet Kumar Pankaj Disclaimer There is no claim of the originality of the material and it given only for students to study. This is mare compilation from various books, articles, and magazine for the students. A Substantial portion of reading is from compiled reading of Algappa University and IGNOU. UNIT I Tribes: Definition Concept of Tribes Tribes of India: Definition Characteristics of the tribal community Historical Background of Tribes- Socio- economic Condition of Tribes in Pre and Post Colonial Period Culture and Language of Major Tribes PVTGs Geographical Distribution of Tribes MoTA Constitutional Safeguards UNIT II Understanding Tribal Culture in India-Melas, Festivals, and Yatras Ghotul Samakka Sarakka Festival North East Tribal Festival Food habits, Religion, and Lifestyle Tribal Culture and Economy UNIT III Contemporary Issues of Tribes-Health, Education, Livelihood, Migration, Displacement, Divorce, Domestic Violence and Dowry UNIT IV Tribal Movement and Tribal Leaders, Land Reform Movement, The Santhal Insurrection, The Munda Rebellion, The Bodo Movement, Jharkhand Movement, Introduction and Origine of other Major Tribal Movement of India and its Impact, Tribal Human Rights UNIT V Policies and Programmes: Government Interventions for Tribal Development Role of Tribes in Economic Growth Importance of Education Role of Social Work Definition Of Tribe A series of definition have been offered by the earlier Anthropologists like Morgan, Tylor, Perry, Rivers, and Lowie to cover a social group known as tribe. These definitions are, by no means complete and these professional Anthropologists have not been able to develop a set of precise indices to classify groups as ―tribalǁ or ―non tribalǁ. -

Scheduled Tribes

Annual Report 2008-09 Ministry of Tribal Affairs Photographs Courtesy: Front Cover - Old Bonda by Shri Guntaka Gopala Reddy Back Cover - Dha Tribal in Wheat Land by Shri Vanam Paparao CONTENTS Chapters 1 Highlights of 2008-09 1-4 2 Activities of Ministry of Tribal Affairs- An Overview 5-7 3 The Ministry: An Introduction 8-16 4 National Commission for Scheduled Tribes 17-19 5 Tribal Development Strategy and Programmes 20-23 6 The Scheduled Tribes and the Scheduled Area 24-86 7 Programmes under Special Central Assistance to Tribal Sub-Plan 87-98 (SCA to TSP) and Article 275(1) of the Constitution 8 Programmes for Promotion of Education 99-114 9 Programmes for Support to Tribal Cooperative Marketing 115-124 Development Federation of India Ltd. and State level Corporations 10 Programmes for Promotion of Voluntary Action 125-164 11 Programmes for Development of Particularly Vulnerable 165-175 Tribal Groups (PTGs) 12 Research, Information and Mass Media 176-187 13 Focus on the North Eastern States 188-191 14 Right to Information Act, 2005 192-195 15 Draft National Tribal Policy 196-197 16 Displacement, Resettlement and Rehabilitation of Scheduled Tribes 198 17 Gender Issues 199-205 Annexures 3-A Organisation Chart - Ministry of Tribal Affairs 13 3-B Statement showing details of BE, RE & Expenditure 14-16 (Plan) for the years 2006-07, 2007-08 & 2008-09 5-A State-wise / UT- wise details of Annual Plan (AP) outlays for 2008-09 23 & status of the TSP formulated by States for Annual Plan (AP) 2008-09. 6-A Demographic Statistics : 2001 Census 38-39 -

The Importance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 32 Number 1 Ladakh: Contemporary Publics and Politics Article 13 No. 1 & 2 8-1-2013 The mpI ortance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil Radhika Gupta Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious & Ethnic Diversity, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Gupta, Radhika (2012) "The mporI tance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 32: No. 1, Article 13. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol32/iss1/13 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RADHIKA GUPTA MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGIOUS & ETHNIC DIVERSITY THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING LADAKHI: AFFECT AND ARTIFICE IN KARGIL Ladakh often tends to be associated predominantly with its Tibetan Buddhist inhabitants in the wider public imagination both in India and abroad. It comes as a surprise to many that half the population of this region is Muslim, the majority belonging to the Twelver Shi‘i sect and living in Kargil district. This article will discuss the importance of being Ladakhi for Kargili Shias through an ethnographic account of a journey I shared with a group of cultural activists from Leh to Kargil. -

Land Laws, Administration and Forced Displacement in Andhra Pradesh, India

CESS MONOGRAPH 35 Land Laws, Administration and Forced Displacement in Andhra Pradesh, India C. Ramachandraiah A. Venkateswarlu CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL STUDIES Begumpet, Hyderabad-500016 October, 2014 CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL STUDIES MONOGRAPH SERIES Number - 35 October, 2014 Series Editor : M. Gopinath Reddy © 2014, Copyright Reserved Centre for Economic and Social Studies Hyderabad Note: The views expressed in this document are solely those of the individual author(s). Rs. 200/- Published by : Centre for Economic and Social Studies Begumpet, Hyderabad-500 016 Ph : 040-23402789, 23416780, Fax : 040-23406808 Email : [email protected], www.cess.ac.in Printed by : Vidya Graphics 1-8-724/33, Padma Colony, Nallakunta, Hyderabad - 44 Foreword This study by Dr C. Ramachandraiah and Dr A. Venkateswarlu has been taken up in the context of large scale acquisition of agricultural lands for Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and other projects which has become an issue of serious contestation in recent years. The study is very timely as land administration and land rights of vulnerable groups of people have become major issues of public concern in recent years. The authors have made a sincere attempt to analyse the land laws and administration, assignment of lands, land acquisition, resettlement & rehabilitation policies etc., in Andhra Pradesh. They have examined two case studies - Kakinada SEZ and Polavaram project - to examine the issues of forced land acquisition and resistance. At the outset, it should be noted that the state of Andhra Pradesh was bifurcated into Andhra Pradesh and Telangana states with effect from 2 June 2014. This study was taken up before bifurcation. -

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads - A Literature Review Anita Sharma CREATE PATHWAYS TO ACCESS Research Monograph No. 58 January 2011 University of Sussex Centre for International Education The Consortium for Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) is a Research Programme Consortium supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Its purpose is to undertake research designed to improve access to basic education in developing countries. It seeks to achieve this through generating new knowledge and encouraging its application through effective communication and dissemination to national and international development agencies, national governments, education and development professionals, non-government organisations and other interested stakeholders. Access to basic education lies at the heart of development. Lack of educational access, and securely acquired knowledge and skill, is both a part of the definition of poverty, and a means for its diminution. Sustained access to meaningful learning that has value is critical to long term improvements in productivity, the reduction of inter- generational cycles of poverty, demographic transition, preventive health care, the empowerment of women, and reductions in inequality. The CREATE partners CREATE is developing its research collaboratively with partners in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The lead partner of CREATE is the Centre for International Education at the University of Sussex. The partners are: -

Primary Census Abstract, Series-31

~~ ~I~d qft \if...,JI OI'11 2001 CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 ~ffi-31 Series-31 'tIT2:I ft:l Cf) \J1 ~ ~ I UI ~ I '("II '< Primary Census Abstract WR \JHfi'L(~H : ftHuft q)"-5 ~ \11'1fi'LclIl : ~ q)"-6, ~ \11 '1 t1'LclI 1 : ~ en-7 3f1~ d \111 Rt ll) qft \11 +~4 'LclIl : ~ q)"-8, 3f 1~fil d \11 '1 \111 Rt m<tt \11;:Ifi'LclIl : ~ co -9 Total Population: Table A-5 Institutional Population: Table A-G, Houseless Population: Table A-7 Scheduled Castes Population: Table A-B, Scheduled Tribes Population: Table A-9 Vfrl J IUl'11 PI~~II(>1l1, TJ1crr Directorate of Census Operations, Goa Product Code Number 30-009-2001-Cen-Book ii !,H-qICl'iI ......................... , ................. ,"."' .. ",."', ... ',.', ............ ,."., .. ,, .... ,, .... , .... " .. " .. , .. ,.".,. v-vi 3IT~"'."'., .. ,.".,., .. , ..... ,." .. , .. " .. """".".".,., .. ",", .. , .... "",",.".,', .. , .... ,.,, .. , .. ,."".,."",.,.", IX ~ ~ ~ it "',",", ... ,.. " .. ,., ... ,..... ".".,.".,, .................... ,." ........ ,..... ,.......... ,", ..... ,",xi-xxi 'QTCRl?~9 ........................ , .................. , ......................................................................... xxiii-xxv ~ \J1'i l IOI'i1 fiCfJ<:>q'iI~ lfCT l:lft~ ........ " ........................................ " ....... "" .......... " .. xxvii-xxxv ~~ Pc) ~ ~ .. I V11Q'l'9-~!:! tkllQ ............................ ".,',.,",." .... " .. ,.".,"", ... : ......... , ......................... XXXVII-X fc)~c>ll"iOIIC1iCf) fclq'!fUl~~i ...................................................................................................