Van Dyck in More Than Twenty Years Takes a Comprehensive Look at the Artist’S Activity and Process As a Portraitist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galileo in Rome Galileo in Rome

Galileo in Rome Galileo in Rome The Rise and Fall of a Troublesome Genius William R. Shea and Mariano Artigas Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Copyright © 2003 by Oxford University Press, Inc. First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 2003 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2004 ISBN 0-19-517758-4 (pbk) Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. The Library of Congress has catalogued the cloth edition as follows: Artigas, Mariano. Galileo in Rome : the rise and fall of a troublesome genius / Mariano Artigas and William R. Shea. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-19-516598-5 1. Galilei, Galileo, 1564-1642—Journeys—Italy—Rome. 2. Religion and science—History—16th century. 3. Astronomers—Italy—Biography. I. Shea, William R. II. Title. QB36.G2 A69 2003 520'.92—dc21 2003004247 Book design by planettheo.com 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper CONTENTS ACKNO W L E D G E M E N T S vii I N TRO D U C TIO N ix CHA P TER O N E Job Hunting and the Path -

THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

THE POWER OF BEAUTY IN RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] THE WINDSOR BEAUTIES www.shafe.uk • It is 1660, the English Civil War is over and the experiment with the Commonwealth has left the country disorientated. When Charles II was invited back to England as King he brought new French styles and sexual conduct with him. In particular, he introduced the French idea of the publically accepted mistress. Beautiful women who could catch the King’s eye and become his mistress found that this brought great wealth, titles and power. Some historians think their power has been exaggerated but everyone agrees they could influence appointments at Court and at least proposition the King for political change. • The new freedoms introduced by the Reformation Court spread through society. Women could appear on stage for the first time, write books and Margaret Cavendish was the first British scientist. However, it was a totally male dominated society and so these heroic women had to fight against established norms and laws. Notes • The Restoration followed a turbulent twenty years that included three English Civil Wars (1642-46, 1648-9 and 1649-51), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53) and the Protectorate (1653-59) under Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) personal rule. • Following the Restoration of the Stuarts, a small number of court mistresses and beauties are renowned for their influence over Charles II and his courtiers. They were immortalised by Sir Peter Lely as the ‘Windsor Beauties’. Today, I will talk about Charles II and his mistresses, Peter Lely and those portraits as well as another set of portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’ which were painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during the reign of William III and Mary II. -

The Entombment, Peter Paul Rubens

J. Paul Getty Museum Education Department Who's Afraid of Contemporary Art? Information and Questions for Teaching The Entombment, Peter Paul Rubens The Entombment Peter Paul Rubens Flemish, about 1612 Oil on canvas 51 5/8 x 51 1/4 in. 93.PA.9 Questions for Teaching Look at each character in this painting. Pay particular attention to the pose of the bodies, the facial expressions, and hand gestures. How does the body language of each figure communicate emotion and contribute to the narrative of the story? What do the background details tell you about the story? (In this case, the background details help to locate the story: the rock walls behind the figures, and the stone slab that supports Christ’s corpse show the event is taking place inside Christ’s tomb. Rubens crops the image closely, forcing the viewer to really focus on the emotion of the characters and the violence done to the body of Christ.) What characteristics of this 17th-century painting are similar to contemporary artist Bill Viola’s video installation Emergence (see images of the work in this curriculum’s Image Bank)? What characteristics of the two artworks are different? Peter Paul Rubens made this painting for an altarpiece inside a Catholic chapel. It was intended to serve as a meditational device—to focus the viewer’s attention on the suffering of Christ and inspire devotion. Pretend that you are not familiar with the religious story depicted in the painting. What kinds of emotional responses do you have to this work of art? What visual elements of the painting make you feel this way? Which artwork do you think conveys emotions better, Bill Viola’s Emergence or Peter Paul Rubens’s The Entombment? How does the medium of the artwork—painting or video—affect your opinion? Background Information In this painting, Peter Paul Rubens depicted the moment after his Crucifixion, when Christ is placed into the tomb before his Resurrection. -

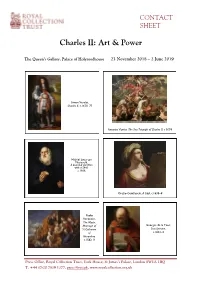

Charles II: Art & Power

CONTACT SHEET Charles II: Art & Power The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse 23 November 2018 – 2 June 2019 Simon Verelst, Charles II, c.1670–75 Antonio Verrio, The Sea Triumph of Charles II, c.1674 Michiel Jansz van Miereveld, A bearded old Man with a Shell, c.1606 Orazio Gentileschi, A Sibyl, c.1635–8 Paolo Veronese, The Mystic Marriage of Georges de la Tour, St Catherine Saint Jerome, of c.1621–3 Alexandria, c.1562–9 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk Cristofano Allori, Judith with the Parmigianino, Head of Pallas Athena, Holofernes, c.1531–8 1613 Sir Peter Lely, Sir Peter Lely, Barbara Villiers, Catherine of Duchess of Braganza, Cleveland, c.1663–65 c.1665 Pierre Fourdrinier, The Royal Palace of Holyrood House, Side table, c.1670 c.1753 Leonardo da Vinci, The muscles of the Hans Holbein the back and arm, Younger, Frances, c. 1508 Countess of Surrey, c.1532–3 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk A selection of images is available at www.picselect.com. For further information contact Royal Collection Trust Press Office +44 (0)20 7839 1377 or [email protected]. Notes to Editors Royal Collection Trust, a department of the Royal Household, is responsible for the care of the Royal Collection and manages the public opening of the official residences of The Queen. -

Frans Snyders

Frans Snyders (Antwerp 1579 - Antwerp 1657) A Buck, a Lobster on a China Plate, a Squirrel in a Basket of Fruit, Artichokes and a Boar’s Head in a Tureen, with Birds, a White Napkin and Asparagus on a Draped Table bearing a collection inventory number (lower right) oil on canvas 117 x 179 cm (46 x 70½ in) N A TABLE DRAPED WITH A SCARLET CLOTH, the imposing figure of a dead buck deer occupies the centre of the composition. Around the magnificent animal, which has been gutted ready for quartering and hanging, manifestations of plenty take the form of ooverflowing baskets of fruit and vegetables, an enormous boar’s head, a red lobster, and a string of small birds. The dark, neutral wall behind the table serves as a sober backdrop to emphasize still more the exuberant feast of colour and form inherent to this still-life. A tall basket to the left of the composition overflows with grapes, peaches and apricots, their leaves and tendrils creating a swirling pattern around it: a red squirrel balances atop the fruit, stretching towards the most inaccessible apricot with delightful illogicality. To the right, another receptacle holds, among oranges and artichokes, the gigantic severed head of a wild boar, probably hunted at the same time as the buck. On the table next to the deer’s head Frans Snyders, The Fish Market, 1620s, are bunches of asparagus, and further left a dead partridge, a woodcock, The Hermitage, St. Petersburg (Figure 1) and a string of small birds such as bullfinches. A black cat, bearing a peculiarly malevolent expression in its orange eyes, prepares to pounce Frans Snyders specialised in still-life and animal paintings, and over the stag’s neck to scavenge one of the birds. -

Lots of Fruit MEDIUM: Crayon BIG IDEA

TITLE of Gr 1 Project: Lots of Fruit Read and discuss the book Little Oink by Amy Krouse Rosenthal. MEDIUM: Crayon OBJECTIVES: The student Will Be Able To: BIG IDEA: Is Lots Better than One? 1. acknowledge that art can represent things in life ESSENTIAL QUESTION: Would you choose to eat 2. acknowledge that marks can define an object lots of fruit or just one piece? 3. identify and use light and shadow for 3D effect MATERIALS: 90 lb white cardstock 8.5X11” 4. create visual balance paper; pencils; crayons; pencils; lots of fruit 5. understand that art has significance 6. understand and use art vocabulary & concepts STUDIO PROCEDURES: 1. Look at the PPt about RELATED HISTORIC ARTWORK: Frans Snyders Frans Snyders pointing out the super realism of PPt the objects and the abundance of objects. 2. Have the discussion using the key questions. 3. If Still Life with available, read the book Little Oink by Amy Grapes and Krouse Rosenthal. 4. Place an arrangement of Game by Frans fruit in front of the students, preferable in a Snyders, c. 1630, bowl. Suggestion would be to make a central still Oil paint on life and arrange their tables/desks around the Panel arrangement. 5. Demonstrate how to draw the TEKS: Grades 1. 1. a. b. (info from environment; still life using basic shapes as a guide. Point out use element of line, color and shape; use to the students where the fruit is light and where principle of balance) it is dark. Also encourage the students to fill the 2. -

Edward Hawke Locker and the Foundation of The

EDWARD HAWKE LOCKER AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF NAVAL ART (c. 1795-1845) CICELY ROBINSON TWO VOLUMES VOLUME II - ILLUSTRATIONS PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2013 2 1. Canaletto, Greenwich Hospital from the North Bank of the Thames, c.1752-3, NMM BHC1827, Greenwich. Oil on canvas, 68.6 x 108.6 cm. 3 2. The Painted Hall, Greenwich Hospital. 4 3. John Scarlett Davis, The Painted Hall, Greenwich, 1830, NMM, Greenwich. Pencil and grey-blue wash, 14¾ x 16¾ in. (37.5 x 42.5 cm). 5 4. James Thornhill, The Main Hall Ceiling of the Painted Hall: King William and Queen Mary attended by Kingly Virtues. 6 5. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: King William and Queen Mary. 7 6. James Thornhill, Detail of the upper hall ceiling: Queen Anne and George, Prince of Denmark. 8 7. James Thornhill, Detail of the south wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of William III at Torbay. 9 8. James Thornhill, Detail of the north wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of George I at Greenwich. 10 9. James Thornhill, West Wall of the Upper Hall: George I receiving the sceptre, with Prince Frederick leaning on his knee, and the three young princesses. 11 10. James Thornhill, Detail of the west wall of the Upper Hall: Personification of Naval Victory 12 11. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: British man-of-war, flying the ensign, at the bottom and a captured Spanish galleon at top. 13 12. ‘The Painted Hall’ published in William Shoberl’s A Summer’s Day at Greenwich, (London, 1840) 14 13. -

A Suit of Silver: the Underdress of a Knight of the Garter in the Late Seventeenth Century

Costume, vol. 48, no. 1, 2014 A Suit of Silver: The Underdress of a Knight of the Garter in the Late Seventeenth Century By D W This paper describes the cut and construction of the doublet and hose worn as underdress to the robes and insignia of the Knights of the Most Noble Order of the Garter at the English Court under Charles II. This example belonged to Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond (1639–1672), who was created a knight of the Garter in 1661. It is interesting on several counts: the dominant textile is a very pure cloth of silver; the elaborate hose are constructed with reference to earlier seventeenth-century models; the garments exemplify Charles II’s understanding of the importance of ceremony to successful kingship. The suit was conserved for an exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and the essay gives some account of discoveries made through this process. In addition, the garments are placed in the context of late seventeenth- century dress. : Charles II, Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond, Order of the Garter, ceremonial dress, seventeenth-century men’s clothing, seventeenth-century tailoring T N M S, Edinburgh, UK has in its possession a set of clothes comprising a late seventeenth-century ceremonial doublet and trunk hose, part of the underdress of the robes of the Order of the Garter (Figures 1 and 2).1 The garments are made of cloth of silver and were once worn by Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond (1639–1672), who was created a knight of the Garter in 1661. -

Dyck, Sir Anthony Van

Dyck, Sir Anthony van Dyck, Sir Anthony van (1599-1641). Apart from Rubens, the greatest Flemish painter of the 17th century. In 1609 he began his apprenticeship with Hendrick van Balen in his native Antwerp and he was exceptionally precocious. Although he did not become a master in the painters' guild until 1618, there is evidence that he was working independently for some years before this, even though this was forbidden by guild regulations. Probably soon after graduating he entered Rubens's workshop. Strictly speaking he should not be called Rubens's pupil, as he was an accomplished painter when he went to work for him. Nevertheless the two years he spent with Rubens were decisive and Rubens's influence upon his painting is unmistakable, although ven Dyck's style was always less energetic. In 1620 van Dyck went to London, where he spent a few months in the service of James I (1566-1625), then in 1621 to Italy, where he travelled a great deal, and toned down the Flemish robustness of his early pictures to create the refined and elegant style which remained characteristic of his work for the rest of his life. His great series of Baroque portraits of the Genoese aristocracy established the `immortal' type of nobleman, with proud mien and slender figure. The years 1628-32 were spent mainly at Antwerp. From 1632 until his death he was in England -- except for visits to the Continent -- as painter to Charles I, from whom he received a knighthood. During these years he was occupied almost entirely with portraits. -

Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snyders, the Head of Medusa, C

Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snyders, The Head of Medusa, c. 1617-18 Oil on canvas, 34.5 x 44.5 in. (87.5 x 113 cm.) New York Private Collection Provenance: (Possibly) Nicolaas Sohier, Amsterdam;1 Christopher Gibbs Ltd, London, 1977; Christies, London, 14 December 1979, Lot 128; Mr. and Mrs. William Llewelyn, Plas Teg House, Wales; Private Collection, United Kingdom. Literature: The Burlington Magazine, no. 119, September 1977, p. LXXIII, ill. J.G. van Gelder, “Das Rubens-Bild. Ein Rückblick,” in: Peter Paul Rubens, Werk, und Nachruhm, Augsburg 1981, p. 38, no. 12. H. Robels, Frans Snyders: Stilleben und Tiermaler, Munich 1989, p. 371, no. 276B2. P.C. Sutton, The Age of Rubens, Boston, 1993, p. 247, no. 16. According to Ovid (Metamorphoses IV:770), the ravishing but mortal Medusa was particularly admired for her beautiful hair. After being assaulted by Neptune in Minerva’s temple, the enraged goddess transformed Medusa’s strands of hair into venomous snakes and her previously pretty face becomes so horrific that the mere sight of it turns onlookers into stone. Perseus, avoiding eye contact by looking at her reflection in his mirrored shield, decapitated Medusa in her sleep and eventually gave her head to Minerva, who wore it on her shield. Exemplifying female rage, Medusa is a misogynist projection and a fantasy of her power. When Perseus decapitates Medusa, he not only vanquishes her, but gains control over her deadly weaponry although he cannot contain the serpents disseminating evil. There are a number of relevant precedents for The Head of Medusa (Fig. -

S 11 T Is Ii Nn 1N 1101 In

s 11 T i s ii n n H- w 3 £ 1n 1101 i n <W O W hf Washington 25, D.C NEWS RELEASE DATE For release July 11, 1962 Washington,. D.C., July 11, 1962. The Traveling Exhibition Service of the Smithsonian Institution announced today a forthcoming exhibition of major importance, "Old Master Drawings from Chatsworth," which will open at the National Gallery of Art on October 28th. The lik magnificent drawings which comprise the exhibition are on loan from one of the finest private art collections in England, formed by the second Duke of Devonshire in the late 17th and early l8th centuries and enlarged by his descendants. Selected by Mr. A. E. Popham, for many years Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, they illustrate the art of drawing in Europe from the Renaissance to the end of the 17th century. Chatsworth is one of the most famous of the great British country houses, and only on two occasions has an exhibition representing its wealth of drawings been attempted. Both were in England. Perhaps the outstanding feature of the collection is the series of landscape drawings by Rembrandt, ten of which are to be shown. Among the kj other artists represented are Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Giulio Romano, Mantegna, Correggio, Parmigianino, Primaticcio, Veronese, Rosso, Bruegel, Van i) ~~ Dyck, Rubens^ Durer, Holbein, and Inigo Jones. The earliest drawing in the exhibition is by an anonymous 15th century Sienese artist showing the "Betrayal of Christ" on one side and a finished composition representing "Christ Before the High Priest" on the reverse. -

1 Aldred/Nattes/RS Corr 27/12/10 13:14 Page 1

1 Tittler Roberts:1 Aldred/Nattes/RS corr 27/12/10 13:14 Page 1 Volume XI, No. 2 The BRITISH ART Journal Discovering ‘T. Leigh’ Tracking the elusive portrait painter through Stuart England and Wales1 Stephanie Roberts & Robert Tittler 1 Robert Davies III of Gwysaney by Thomas Leigh, 1643. Oil on canvas, 69 x 59 cm. National Museum Wales, Cardiff. With permission of Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales n a 1941 edition of The Oxford Journal, Maurice 2 David, 1st Earl Barrymore by Thomas Leigh, 1636. Oil on canvas, 88 x 81 Brockwell, then Curator of the Cook Collection at cm. Current location unknown © Christie’s Images Ltd 2008 IDoughty House in Richmond, Surrey, submitted the fol- lowing appeal for information: [Brockwell’s] vast amount of data may not amount to much T. LEIGH, PORTRAIT-PAINTER, 1643. Information is sought in fact,’5 but both agreed that the little available information regarding the obscure English portrait-painter T. Leigh, who on Leigh was worth preserving nonetheless. Regrettably, signed, dated and suitably inscribed a very limited number of Brockwell’s original notes are lost to us today, and since then pictures – and all in 1643. It is strange that we still know nothing no real attempt has been made to further identify Leigh, until about his origin, place and date of birth, residence, marriage and now. death… Much research proves that the biographical facts Brockwell eventually sold the portrait of Robert Davies to regarding T. Leigh recited in the Burlington Magazine, 1916, xxix, the National Museum of Wales in 1948, thus bringing p.3 74, and in Thieme Becker’s Allgemeines Lexikon of 1928 are ‘Thomas Leigh’ to national attention as a painter of mid-17th too scanty and not completely accurate.