Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680): Dutch Classicist, English Portraitist, and Collector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

THE POWER OF BEAUTY IN RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] THE WINDSOR BEAUTIES www.shafe.uk • It is 1660, the English Civil War is over and the experiment with the Commonwealth has left the country disorientated. When Charles II was invited back to England as King he brought new French styles and sexual conduct with him. In particular, he introduced the French idea of the publically accepted mistress. Beautiful women who could catch the King’s eye and become his mistress found that this brought great wealth, titles and power. Some historians think their power has been exaggerated but everyone agrees they could influence appointments at Court and at least proposition the King for political change. • The new freedoms introduced by the Reformation Court spread through society. Women could appear on stage for the first time, write books and Margaret Cavendish was the first British scientist. However, it was a totally male dominated society and so these heroic women had to fight against established norms and laws. Notes • The Restoration followed a turbulent twenty years that included three English Civil Wars (1642-46, 1648-9 and 1649-51), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53) and the Protectorate (1653-59) under Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) personal rule. • Following the Restoration of the Stuarts, a small number of court mistresses and beauties are renowned for their influence over Charles II and his courtiers. They were immortalised by Sir Peter Lely as the ‘Windsor Beauties’. Today, I will talk about Charles II and his mistresses, Peter Lely and those portraits as well as another set of portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’ which were painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during the reign of William III and Mary II. -

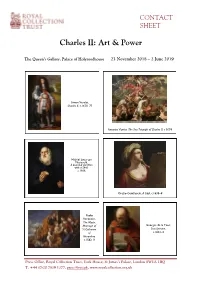

Charles II: Art & Power

CONTACT SHEET Charles II: Art & Power The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse 23 November 2018 – 2 June 2019 Simon Verelst, Charles II, c.1670–75 Antonio Verrio, The Sea Triumph of Charles II, c.1674 Michiel Jansz van Miereveld, A bearded old Man with a Shell, c.1606 Orazio Gentileschi, A Sibyl, c.1635–8 Paolo Veronese, The Mystic Marriage of Georges de la Tour, St Catherine Saint Jerome, of c.1621–3 Alexandria, c.1562–9 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk Cristofano Allori, Judith with the Parmigianino, Head of Pallas Athena, Holofernes, c.1531–8 1613 Sir Peter Lely, Sir Peter Lely, Barbara Villiers, Catherine of Duchess of Braganza, Cleveland, c.1663–65 c.1665 Pierre Fourdrinier, The Royal Palace of Holyrood House, Side table, c.1670 c.1753 Leonardo da Vinci, The muscles of the Hans Holbein the back and arm, Younger, Frances, c. 1508 Countess of Surrey, c.1532–3 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk A selection of images is available at www.picselect.com. For further information contact Royal Collection Trust Press Office +44 (0)20 7839 1377 or [email protected]. Notes to Editors Royal Collection Trust, a department of the Royal Household, is responsible for the care of the Royal Collection and manages the public opening of the official residences of The Queen. -

Edward Hawke Locker and the Foundation of The

EDWARD HAWKE LOCKER AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF NAVAL ART (c. 1795-1845) CICELY ROBINSON TWO VOLUMES VOLUME II - ILLUSTRATIONS PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2013 2 1. Canaletto, Greenwich Hospital from the North Bank of the Thames, c.1752-3, NMM BHC1827, Greenwich. Oil on canvas, 68.6 x 108.6 cm. 3 2. The Painted Hall, Greenwich Hospital. 4 3. John Scarlett Davis, The Painted Hall, Greenwich, 1830, NMM, Greenwich. Pencil and grey-blue wash, 14¾ x 16¾ in. (37.5 x 42.5 cm). 5 4. James Thornhill, The Main Hall Ceiling of the Painted Hall: King William and Queen Mary attended by Kingly Virtues. 6 5. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: King William and Queen Mary. 7 6. James Thornhill, Detail of the upper hall ceiling: Queen Anne and George, Prince of Denmark. 8 7. James Thornhill, Detail of the south wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of William III at Torbay. 9 8. James Thornhill, Detail of the north wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of George I at Greenwich. 10 9. James Thornhill, West Wall of the Upper Hall: George I receiving the sceptre, with Prince Frederick leaning on his knee, and the three young princesses. 11 10. James Thornhill, Detail of the west wall of the Upper Hall: Personification of Naval Victory 12 11. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: British man-of-war, flying the ensign, at the bottom and a captured Spanish galleon at top. 13 12. ‘The Painted Hall’ published in William Shoberl’s A Summer’s Day at Greenwich, (London, 1840) 14 13. -

A Suit of Silver: the Underdress of a Knight of the Garter in the Late Seventeenth Century

Costume, vol. 48, no. 1, 2014 A Suit of Silver: The Underdress of a Knight of the Garter in the Late Seventeenth Century By D W This paper describes the cut and construction of the doublet and hose worn as underdress to the robes and insignia of the Knights of the Most Noble Order of the Garter at the English Court under Charles II. This example belonged to Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond (1639–1672), who was created a knight of the Garter in 1661. It is interesting on several counts: the dominant textile is a very pure cloth of silver; the elaborate hose are constructed with reference to earlier seventeenth-century models; the garments exemplify Charles II’s understanding of the importance of ceremony to successful kingship. The suit was conserved for an exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and the essay gives some account of discoveries made through this process. In addition, the garments are placed in the context of late seventeenth- century dress. : Charles II, Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond, Order of the Garter, ceremonial dress, seventeenth-century men’s clothing, seventeenth-century tailoring T N M S, Edinburgh, UK has in its possession a set of clothes comprising a late seventeenth-century ceremonial doublet and trunk hose, part of the underdress of the robes of the Order of the Garter (Figures 1 and 2).1 The garments are made of cloth of silver and were once worn by Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond (1639–1672), who was created a knight of the Garter in 1661. -

S 11 T Is Ii Nn 1N 1101 In

s 11 T i s ii n n H- w 3 £ 1n 1101 i n <W O W hf Washington 25, D.C NEWS RELEASE DATE For release July 11, 1962 Washington,. D.C., July 11, 1962. The Traveling Exhibition Service of the Smithsonian Institution announced today a forthcoming exhibition of major importance, "Old Master Drawings from Chatsworth," which will open at the National Gallery of Art on October 28th. The lik magnificent drawings which comprise the exhibition are on loan from one of the finest private art collections in England, formed by the second Duke of Devonshire in the late 17th and early l8th centuries and enlarged by his descendants. Selected by Mr. A. E. Popham, for many years Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, they illustrate the art of drawing in Europe from the Renaissance to the end of the 17th century. Chatsworth is one of the most famous of the great British country houses, and only on two occasions has an exhibition representing its wealth of drawings been attempted. Both were in England. Perhaps the outstanding feature of the collection is the series of landscape drawings by Rembrandt, ten of which are to be shown. Among the kj other artists represented are Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Giulio Romano, Mantegna, Correggio, Parmigianino, Primaticcio, Veronese, Rosso, Bruegel, Van i) ~~ Dyck, Rubens^ Durer, Holbein, and Inigo Jones. The earliest drawing in the exhibition is by an anonymous 15th century Sienese artist showing the "Betrayal of Christ" on one side and a finished composition representing "Christ Before the High Priest" on the reverse. -

1 Aldred/Nattes/RS Corr 27/12/10 13:14 Page 1

1 Tittler Roberts:1 Aldred/Nattes/RS corr 27/12/10 13:14 Page 1 Volume XI, No. 2 The BRITISH ART Journal Discovering ‘T. Leigh’ Tracking the elusive portrait painter through Stuart England and Wales1 Stephanie Roberts & Robert Tittler 1 Robert Davies III of Gwysaney by Thomas Leigh, 1643. Oil on canvas, 69 x 59 cm. National Museum Wales, Cardiff. With permission of Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales n a 1941 edition of The Oxford Journal, Maurice 2 David, 1st Earl Barrymore by Thomas Leigh, 1636. Oil on canvas, 88 x 81 Brockwell, then Curator of the Cook Collection at cm. Current location unknown © Christie’s Images Ltd 2008 IDoughty House in Richmond, Surrey, submitted the fol- lowing appeal for information: [Brockwell’s] vast amount of data may not amount to much T. LEIGH, PORTRAIT-PAINTER, 1643. Information is sought in fact,’5 but both agreed that the little available information regarding the obscure English portrait-painter T. Leigh, who on Leigh was worth preserving nonetheless. Regrettably, signed, dated and suitably inscribed a very limited number of Brockwell’s original notes are lost to us today, and since then pictures – and all in 1643. It is strange that we still know nothing no real attempt has been made to further identify Leigh, until about his origin, place and date of birth, residence, marriage and now. death… Much research proves that the biographical facts Brockwell eventually sold the portrait of Robert Davies to regarding T. Leigh recited in the Burlington Magazine, 1916, xxix, the National Museum of Wales in 1948, thus bringing p.3 74, and in Thieme Becker’s Allgemeines Lexikon of 1928 are ‘Thomas Leigh’ to national attention as a painter of mid-17th too scanty and not completely accurate. -

1 the Early Royal Society and Visual Culture Sachiko Kusukawa1 Trinity

The Early Royal Society and Visual Culture Sachiko Kusukawa1 Trinity College, Cambridge [Abstract] Recent studies have fruitfully examined the intersection between early modern science and visual culture by elucidating the functions of images in shaping and disseminating scientific knowledge. Given its rich archival sources, it is possible to extend this line of research in the case of the Royal Society to an examination of attitudes towards images as artefacts –manufactured objects worth commissioning, collecting and studying. Drawing on existing scholarship and material from the Royal Society Archives, I discuss Fellows’ interests in prints, drawings, varnishes, colorants, images made out of unusual materials, and methods of identifying the painter from a painting. Knowledge of production processes of images was important to members of the Royal Society, not only as connoisseurs and collectors, but also as those interested in a Baconian mastery of material processes, including a “history of trades”. Their antiquarian interests led to discussion of painters’ styles, and they gradually developed a visual memorial to an institution through portraits and other visual records. Introduction In the Royal Society Library there is a manuscript (MS/136) entitled “Miniatura or the Art of Lymning” 2 by Edward Norgate (1581-1650), who was keeper of the King’s musical instruments, Windsor Herald, and an art agent for “the collector Earl”, Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel (1586-1646) (Norgate 1997, pp. 1-9). Two versions exist of Norgate’s “Miniatura”, the first of which was 1 written for his friend, Sir Theodore Turquet de Mayerne (1573-1655), and a second, expanded treatise was dedicated to his patron’s son, Henry Frederick Howard, the third Earl of Arundel (1608-1652), also an art connoisseur. -

A Historical and Technical Investigation of Sir Peter Lely's Cimon and Efigenia from the Collection at Doddington Hall

A Historical and Technical Investigation of Sir Peter Lely’s Cimon and Efigenia from the Collection at Doddington Hall. Introduction German Westphalia. The name of Lely, under which he would become famous as an artist, stems from the The Conservation and Art Historical Analysis Project lily, which adorned the gable of his father’s house in 1 at the Courtauld Institute Research Forum aimed to Soest. carry out technical investigation and art historical re- In emulation of Vasari and the Netherlandish search on Sir Peter Lely’s painting Cimon and Efigenia. artist-biographer Karel van Mander, Houbraken wrote The painting came to the Courtauld Gallery in 2012 on the lives of the most famous Dutch artists. Peter for the Lely: A Lyrical Vision exhibition, which focused Lely proves an interesting case, as he seems as much – on Lely’s subject pictures from his earlier years in Eng- or perhaps even more – an English artist. When Lely’s land. After the exhibition, Cimon and Efigenia was soldier-father noticed that his son preferred wielding brought to the conservation department for conser- the brush over the sword and the art of painting over vation treatment. Cimon and Efigenia’s conservation the art of warfare, he sent his 18-year-old son to the treatment, along with previous technical examination Dutch city of Haarlem to study under the painter Frans 2 of the Courtauld Gallery’s Peter Lely subject pictures, Pieter de Grebber. Hardly any work from the time he provided a unique opportunity to further investigate spent in Haarlem is known, however, and it seems that the history of this painting and its place within Lely’s Lely’s career only became truly established when he practice and oeuvre. -

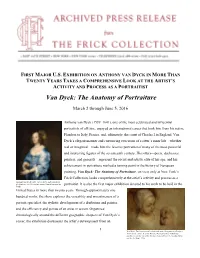

Van Dyck in More Than Twenty Years Takes a Comprehensive Look at the Artist’S Activity and Process As a Portraitist

FIRST MAJOR U.S. EXHIBITION ON ANTHONY VAN DYCK IN MORE THAN TWENTY YEARS TAKES A COMPREHENSIVE LOOK AT THE ARTIST’S ACTIVITY AND PROCESS AS A PORTRAITIST Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture March 2 through June 5, 2016 Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), one of the most celebrated and influential portraitists of all time, enjoyed an international career that took him from his native Flanders to Italy, France, and, ultimately, the court of Charles I in England. Van Dyck’s elegant manner and convincing evocation of a sitter’s inner life—whether real or imagined—made him the favorite portraitist of many of the most powerful and interesting figures of the seventeenth century. His sitters—poets, duchesses, painters, and generals—represent the social and artistic elite of his age, and his achievement in portraiture marked a turning point in the history of European painting. Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture, on view only at New York’s Frick Collection, looks comprehensively at the artist’s activity and process as a Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), Mary, Lady van Dyck, née Ruthven, ca. 1640, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del portraitist. It is also the first major exhibition devoted to his work to be held in the Prado United States in more than twenty years. Through approximately one hundred works, the show explores the versatility and inventiveness of a portrait specialist, the stylistic development of a draftsman and painter, and the efficiency and genius of an artist in action. Organized chronologically around the different geographic chapters of Van Dyck’s career, the exhibition documents the artist’s development from an 1 Van Dyck, The Princesses Elizabeth and Anne, Daughters of Charles I, 1637, oil on canvas, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh; purchased with the aid of the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Scottish Office, and the Art Fund 1996 ambitious young apprentice into the most sought-after portrait painter in Europe. -

From the Commonwealth to the Georgian Period, 1650-1730

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN • The History of the Tate • From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 • From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 • The Georgians, 1730-1780 • Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 • Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 • William Blake • J. M. W. Turner • John Constable • The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

Diploma Lecture Series 2012 Absolutism to Enlightenment

Diploma Lecture Series 2012 Absolutism to enlightenment: European art and culture 1665-1765 Charles II and the restoration Lorraine Kypiotis 15 / 16 February 2012 Lecture summary: The Restoration had an exhilarating bravado characterised by a lavish and flamboyant court. It saw the return of the theatre, a flourishing of the arts and the founding of the Royal Society in a court that was the glamorous and often scandalous centre of a London that would rise from the flames like a phoenix. The return of Charles II to the throne in 1660 marked a moment of political and cultural change almost as dramatic as that brought about by his father’s execution 11 years earlier. After the repressions of the interregnum and the uncertainties and poverty of the exiled court, there was an appetite for exuberance, indulgence and transgression – an appetite that the king came to symbolize. After the puritanical sobriety of Cromwell’s parliament, England once again flourished in the arts and sciences. Charles, and his court patronised a number of scientists, architects, poets and dramatists whose influences were felt far beyond the reign of the “Merry Monarch”. Most importantly in the field of the fine arts, Charles was responsible for the recovery of many of the great paintings in the British Royal Collection that had been sold by the Commonwealth after his father’s execution; for the acquisition of a number of fine works by the great artists of the Baroque; and in his patronage of portraitists such as Sir Peter Lely. Charles and the artists he patronised were responsible for the enduring images of a monarchy restored. -

Dutch and Flemish Art at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts A

DUTCH AND FLEMISH ART AT THE UTAH MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS A Guide to the Collection by Ursula M. Brinkmann Pimentel Copyright © Ursula Marie Brinkmann Pimentel 1993 All Rights Reserved Published by the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112. This publication is made possible, in part, by a grant from the Salt Lake County Commission. Accredited by the CONTENTS Page Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………………………………………..……...7 History of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts and its Dutch and Flemish Collection…………………………….…..……….8 Art of the Netherlands: Visual Images as Cultural Reflections…………………………………………………….....…17 Catalogue……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…31 Explanation of Cataloguing Practices………………………………………………………………………………….…32 1 Unknown Artist (Flemish?), Bust Portrait of a Bearded Man…………………………………………………..34 2 Ambrosius Benson, Elegant Couples Dancing in a Landscape…………………………………………………38 3 Unknown Artist (Dutch?), Visiones Apocalypticae……………………………………………………………...42 4 Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Charity (Charitas) (1559), after a drawing; Plate no. 3 of The Seven Virtues, published by Hieronymous Cock……………………………………………………………45 5 Jan (or Johan) Wierix, Pieter Coecke van Aelst holding a Palette and Brushes, no. 16 from the Cock-Lampsonius Set, first edition (1572)…………………………………………………..…48 6 Jan (or Johan) Wierix, Jan van Amstel (Jan de Hollander), no. 11 from the Cock-Lampsonius Set, first edition (1572)………………………………………………………….……….51 7 Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus, Title Page from Equile. Ioannis Austriaci