Charles II: Art & Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

THE POWER OF BEAUTY IN RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] THE WINDSOR BEAUTIES www.shafe.uk • It is 1660, the English Civil War is over and the experiment with the Commonwealth has left the country disorientated. When Charles II was invited back to England as King he brought new French styles and sexual conduct with him. In particular, he introduced the French idea of the publically accepted mistress. Beautiful women who could catch the King’s eye and become his mistress found that this brought great wealth, titles and power. Some historians think their power has been exaggerated but everyone agrees they could influence appointments at Court and at least proposition the King for political change. • The new freedoms introduced by the Reformation Court spread through society. Women could appear on stage for the first time, write books and Margaret Cavendish was the first British scientist. However, it was a totally male dominated society and so these heroic women had to fight against established norms and laws. Notes • The Restoration followed a turbulent twenty years that included three English Civil Wars (1642-46, 1648-9 and 1649-51), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53) and the Protectorate (1653-59) under Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) personal rule. • Following the Restoration of the Stuarts, a small number of court mistresses and beauties are renowned for their influence over Charles II and his courtiers. They were immortalised by Sir Peter Lely as the ‘Windsor Beauties’. Today, I will talk about Charles II and his mistresses, Peter Lely and those portraits as well as another set of portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’ which were painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during the reign of William III and Mary II. -

Lord Henry Howard, Later 6Th Duke of Norfolk (1628 – 1684)

THE WEISS GALLERY www.weissgallery.com 59 JERMYN STREET [email protected] LONDON, SW1Y 6LX +44(0)207 409 0035 John Michael Wright (1617 – 1694) Lord Henry Howard, later 6th Duke of Norfolk (1628 – 1684) Oil on canvas: 52 ¾ × 41 ½ in. (133.9 × 105.4 cm.) Painted c.1660 Provenance By descent to Reginald J. Richard Arundel (1931 – 2016), 10th Baron Talbot of Malahide, Wardour Castle; by whom sold, Christie’s London, 8 June 1995, lot 2; with The Weiss Gallery, 1995; Private collection, USA, until 2019. Literature E. Waterhouse, Painting in Britain 1530 – 1790, London 1953, p.72, plate 66b. G. Wilson, ‘Greenwich Armour in the Portraits of John Michael Wright’, The Connoisseur, Feb. 1975, pp.111–114 (illus.). D. Howarth, ‘Questing and Flexible. John Michael Wright: The King’s Painter.’ Country Life, 9 September 1982, p.773 (illus.4). The Weiss Gallery, Tudor and Stuart Portraits 1530 – 1660, 1995, no.25. Exhibited Edinburgh, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, John Michael Wright – The King’s Painter, 16 July – 19 September 1982, exh. cat. pp.42 & 70, no.15 (illus.). This portrait by Wright is such a compelling amalgam of forceful assurance and sympathetic sensitivity, that is easy to see why that doyen of British art historians, Sir Ellis Waterhouse, described it in these terms: ‘The pattern is original and the whole conception of the portrait has a quality of nobility to which Lely never attained.’1 Painted around 1660, it is the prime original of which several other studio replicas are recorded,2 and it is one of a number of portraits of sitters in similar ceremonial 1 Ellis Waterhouse, Painting in Britain 1530 to 1790, 4th integrated edition, 1978, p.108. -

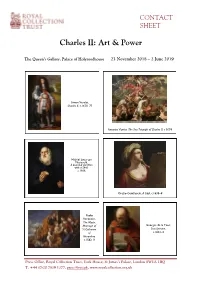

Charles II: Art & Power

CONTACT SHEET Charles II: Art & Power The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse 23 November 2018 – 2 June 2019 Simon Verelst, Charles II, c.1670–75 Antonio Verrio, The Sea Triumph of Charles II, c.1674 Michiel Jansz van Miereveld, A bearded old Man with a Shell, c.1606 Orazio Gentileschi, A Sibyl, c.1635–8 Paolo Veronese, The Mystic Marriage of Georges de la Tour, St Catherine Saint Jerome, of c.1621–3 Alexandria, c.1562–9 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk Cristofano Allori, Judith with the Parmigianino, Head of Pallas Athena, Holofernes, c.1531–8 1613 Sir Peter Lely, Sir Peter Lely, Barbara Villiers, Catherine of Duchess of Braganza, Cleveland, c.1663–65 c.1665 Pierre Fourdrinier, The Royal Palace of Holyrood House, Side table, c.1670 c.1753 Leonardo da Vinci, The muscles of the Hans Holbein the back and arm, Younger, Frances, c. 1508 Countess of Surrey, c.1532–3 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk A selection of images is available at www.picselect.com. For further information contact Royal Collection Trust Press Office +44 (0)20 7839 1377 or [email protected]. Notes to Editors Royal Collection Trust, a department of the Royal Household, is responsible for the care of the Royal Collection and manages the public opening of the official residences of The Queen. -

Edward Hawke Locker and the Foundation of The

EDWARD HAWKE LOCKER AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF NAVAL ART (c. 1795-1845) CICELY ROBINSON TWO VOLUMES VOLUME II - ILLUSTRATIONS PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2013 2 1. Canaletto, Greenwich Hospital from the North Bank of the Thames, c.1752-3, NMM BHC1827, Greenwich. Oil on canvas, 68.6 x 108.6 cm. 3 2. The Painted Hall, Greenwich Hospital. 4 3. John Scarlett Davis, The Painted Hall, Greenwich, 1830, NMM, Greenwich. Pencil and grey-blue wash, 14¾ x 16¾ in. (37.5 x 42.5 cm). 5 4. James Thornhill, The Main Hall Ceiling of the Painted Hall: King William and Queen Mary attended by Kingly Virtues. 6 5. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: King William and Queen Mary. 7 6. James Thornhill, Detail of the upper hall ceiling: Queen Anne and George, Prince of Denmark. 8 7. James Thornhill, Detail of the south wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of William III at Torbay. 9 8. James Thornhill, Detail of the north wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of George I at Greenwich. 10 9. James Thornhill, West Wall of the Upper Hall: George I receiving the sceptre, with Prince Frederick leaning on his knee, and the three young princesses. 11 10. James Thornhill, Detail of the west wall of the Upper Hall: Personification of Naval Victory 12 11. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: British man-of-war, flying the ensign, at the bottom and a captured Spanish galleon at top. 13 12. ‘The Painted Hall’ published in William Shoberl’s A Summer’s Day at Greenwich, (London, 1840) 14 13. -

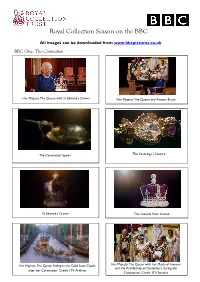

Contact Sheet Working

Royal Collection Season on the BBC All images can be downloaded from www.bbcpictures.co.uk BBC One, The Coronation Her Majesty The Queen with St Edward’s Crown Her Majesty The Queen and Alastair Bruce The Coronation Spoon The Sovereign’s Sceptre St Edward’s Crown The Imperial State Crown Her Majesty The Queen Riding in the Gold State Coach Her Majesty The Queen with her Maids of Honour and the Archbishop of Canterbury during the after her Coronation. Credit: ITV Archive Coronation. Credit: ITV Archive BBC Four Art, Passion & Power: The Story of the Royal Collection Episode One The Bearers of Trophies Charles I with and Bullion, detail from M. de St Antoine by The Triumphs of Caesar by Sir Anthony van Dyck, Andrea Mantegna, 1633 c.1484-92 Andrew Graham-Dixon comes face to face with Charles I by Sir Anthony van Dyck, 1635-before June 1636 Hubert Le Sueur’s portrait bust of Charles I Cicely Heron by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1526-7 Andrew Graham-Dixon in the Picture Gallery at Buckingham Palace Andrew Graham-Dixon in the Picture Gallery Andrew Graham-Dixon in the Picture Gallery at Buckingham Palace at Buckingham Palace BBC Four Art, Passion & Power: The Story of the Royal Collection Episode Two Andrea Odoni by Lorenzo Lotto, 1527 The Bacino di San Marco on Ascension Day by Canaletto, c.1733-4 Frances Stuart, Charles II by Duchess of Richmond by John Michael Wright, Sir Peter Lely, 1662 c.1771-6 The foetus in the womb by Leonardo da Vinci, c.1511 Andrew Graham-Dixon in Venice on the trail of Canaletto Andrew Graham-Dixon in Venice on the -

A Suit of Silver: the Underdress of a Knight of the Garter in the Late Seventeenth Century

Costume, vol. 48, no. 1, 2014 A Suit of Silver: The Underdress of a Knight of the Garter in the Late Seventeenth Century By D W This paper describes the cut and construction of the doublet and hose worn as underdress to the robes and insignia of the Knights of the Most Noble Order of the Garter at the English Court under Charles II. This example belonged to Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond (1639–1672), who was created a knight of the Garter in 1661. It is interesting on several counts: the dominant textile is a very pure cloth of silver; the elaborate hose are constructed with reference to earlier seventeenth-century models; the garments exemplify Charles II’s understanding of the importance of ceremony to successful kingship. The suit was conserved for an exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and the essay gives some account of discoveries made through this process. In addition, the garments are placed in the context of late seventeenth- century dress. : Charles II, Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond, Order of the Garter, ceremonial dress, seventeenth-century men’s clothing, seventeenth-century tailoring T N M S, Edinburgh, UK has in its possession a set of clothes comprising a late seventeenth-century ceremonial doublet and trunk hose, part of the underdress of the robes of the Order of the Garter (Figures 1 and 2).1 The garments are made of cloth of silver and were once worn by Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond (1639–1672), who was created a knight of the Garter in 1661. -

S 11 T Is Ii Nn 1N 1101 In

s 11 T i s ii n n H- w 3 £ 1n 1101 i n <W O W hf Washington 25, D.C NEWS RELEASE DATE For release July 11, 1962 Washington,. D.C., July 11, 1962. The Traveling Exhibition Service of the Smithsonian Institution announced today a forthcoming exhibition of major importance, "Old Master Drawings from Chatsworth," which will open at the National Gallery of Art on October 28th. The lik magnificent drawings which comprise the exhibition are on loan from one of the finest private art collections in England, formed by the second Duke of Devonshire in the late 17th and early l8th centuries and enlarged by his descendants. Selected by Mr. A. E. Popham, for many years Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, they illustrate the art of drawing in Europe from the Renaissance to the end of the 17th century. Chatsworth is one of the most famous of the great British country houses, and only on two occasions has an exhibition representing its wealth of drawings been attempted. Both were in England. Perhaps the outstanding feature of the collection is the series of landscape drawings by Rembrandt, ten of which are to be shown. Among the kj other artists represented are Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Giulio Romano, Mantegna, Correggio, Parmigianino, Primaticcio, Veronese, Rosso, Bruegel, Van i) ~~ Dyck, Rubens^ Durer, Holbein, and Inigo Jones. The earliest drawing in the exhibition is by an anonymous 15th century Sienese artist showing the "Betrayal of Christ" on one side and a finished composition representing "Christ Before the High Priest" on the reverse. -

1 Aldred/Nattes/RS Corr 27/12/10 13:14 Page 1

1 Tittler Roberts:1 Aldred/Nattes/RS corr 27/12/10 13:14 Page 1 Volume XI, No. 2 The BRITISH ART Journal Discovering ‘T. Leigh’ Tracking the elusive portrait painter through Stuart England and Wales1 Stephanie Roberts & Robert Tittler 1 Robert Davies III of Gwysaney by Thomas Leigh, 1643. Oil on canvas, 69 x 59 cm. National Museum Wales, Cardiff. With permission of Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales n a 1941 edition of The Oxford Journal, Maurice 2 David, 1st Earl Barrymore by Thomas Leigh, 1636. Oil on canvas, 88 x 81 Brockwell, then Curator of the Cook Collection at cm. Current location unknown © Christie’s Images Ltd 2008 IDoughty House in Richmond, Surrey, submitted the fol- lowing appeal for information: [Brockwell’s] vast amount of data may not amount to much T. LEIGH, PORTRAIT-PAINTER, 1643. Information is sought in fact,’5 but both agreed that the little available information regarding the obscure English portrait-painter T. Leigh, who on Leigh was worth preserving nonetheless. Regrettably, signed, dated and suitably inscribed a very limited number of Brockwell’s original notes are lost to us today, and since then pictures – and all in 1643. It is strange that we still know nothing no real attempt has been made to further identify Leigh, until about his origin, place and date of birth, residence, marriage and now. death… Much research proves that the biographical facts Brockwell eventually sold the portrait of Robert Davies to regarding T. Leigh recited in the Burlington Magazine, 1916, xxix, the National Museum of Wales in 1948, thus bringing p.3 74, and in Thieme Becker’s Allgemeines Lexikon of 1928 are ‘Thomas Leigh’ to national attention as a painter of mid-17th too scanty and not completely accurate. -

Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680): Dutch Classicist, English Portraitist, and Collector

Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680): Dutch Classicist, English Portraitist, and Collector Brandon Henderson DISSERTATION.COM Boca Raton Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680): Dutch Classicist, English Portraitist, and Collector Copyright © 2001 Brandon Henderson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Dissertation.com Boca Raton, Florida USA • 2008 ISBN-10: 1-59942-688-9 ISBN-13: 978-1-59942-688-4 Due to large file size, some images within this ebook do not appear in high resolution. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to pay tribute to those who contributed significantly to this work. First, I want to thank my Mom and Dad for their love and encouragement throughout this project and always. Second, I want to thank Dr. Megan Aldrich and Dr. Chantal Brotherton-Ratcliffe at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, London, for their comments and suggestions. Third, I want to acknowledge the staff at the British Library and the National Art Library within the Victoria and Albert Museum for their support. And finally, I want to thank the library staff at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, London, for their assistance. ii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ...................................................................................... iv CHAPTER I Introduction -

History of Britain from the Restoration to 1783

History of Britain from the Restoration to 1783 HIS 334J (39245) & EUS 346 (36243) Fall Semester 2016 Charles II of England in Coronation Robes Pulling Down the Statue of George III at Bowling John Michael Wright, c. 1661-1662 Green in Lower Manhattan William Walcutt, 1857 JGB 2.218 Tuesday & Thursday, 12:30 – 2:00 PM Instructor James M. Vaughn [email protected] Office: Garrison 3.218 (ph. 512-232-8268) Office Hours: Thursday, 2:30 – 4:30 PM, and by appointment Teaching Assistant Andrew Wilkins [email protected] Office: The Cactus Cafe in the Texas Union building Office Hours: Tuesday, 2:00 – 4:00 PM, and by appointment Course Description This lecture course surveys the history of England and, after the union with Scotland in 1707, Great Britain from the English Revolution and the restoration of the Stuart monarchy (c. 1640-1660) to the War of American Independence (c. 1775-1783). The kingdom underwent a remarkable transformation during this period, with a powerful monarchy, a persecuting state church, a traditional society, and an agrarian economy giving way to parliamentary rule, religious toleration and pluralism, a dynamic civil society, and a commercial and manufacturing-based economy on the eve of industrialization. How and why did this transformation take place? 1 Over the course of the same period, Great Britain emerged as a leading European and world power with a vast commercial and territorial empire stretching across four continents. How and why did this island kingdom off the northwestern coast of Europe, geopolitically insignificant for much of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, become a Great Power and acquire a global empire in the eighteenth century? How did it do so while remaining a free and open society? This course explores these questions as well as others. -

War and Society the Dutch Republic, 1581–1806

War and Society The Dutch Republic, 1581–1806 Branislav L. Slantchev Department of Political Science, University of California, San Diego Last updated: May 13, 2014 Contents: 1 Medieval Origins 3 2 From Resistance to Rebellion, 1566–1581 6 3 The Republic Forms, 1581–1609 10 4 Political and Fiscal Institutions 17 5 Thirty Years’ War, 1618–48 23 6 The Golden Age, 1650–72 27 7 The Stadtholderate of William III, 1672–1702 31 8 Decline and Fall, 1702–1806 36 8.1 The Second Stadtholderless Period, 1702–46 . ...... 36 8.2 The Orangist Revolution, 1747–80 . 39 8.3 The Patriots and the Batavian Republic, 1787–1806 . ........ 41 9 Paying for the Republic 43 A Maps 54 Required Readings: Anderson, M.S. 1988. War and Society in Europe of the Old Regime, 1618–1789. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. Optional Readings: Blockmans, Wim. 1997. “The Impact of Cities on State Formation: Three Contrasting Territories in the Low Countries, 1300–1500.” In Peter Blickle, Ed. Resistance, Rep- resentation, and Community. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Blockmans, Wim. 1999. “The Low Countries in the Middle Ages.” In Richard Bonney, ed. The Rise of the Fiscal State in Europe, c.1200–1815. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Boogman, J.C. 1979. “The Union of Utrecht: Its Genesis and Consequences.” BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review, 94(3): 377–407. ’t Hart, Marjolein. 1999. “The United Provinces, 1579–1806.” In Richard Bonney, ed. The Rise of the Fiscal State in Europe, c.1200–1815. Oxford: Oxford University Press. De Vries, Jan. 2001. “The Netherlands in the New World: The Legacy of European Fis- cal, Monetary, and Trading Institutions for New World Development from the Seven- teenth to the Nineteenth Centuries.” In Michael D. -

A Guide to the Pictures at Powis Castle Dr Peter Moore a Guide to the Pictures at Powis Castle by Dr Peter Moore

A Guide to the Pictures at Powis Castle Dr Peter Moore A Guide to the Pictures at Powis Castle by Dr Peter Moore Contents A Guide to the Pictures at Powis Castle 3 The Pictures 4 The Smoking Room 4 The State Dining Room 5 The Library 10 The Oak Drawing Room 13 The Gateway 18 The Long Gallery 20 The Walcot Bedroom 24 The Gallery Bedroom 26 The Duke’s Room 26 The Lower Tower Bedroom 28 The Blue Drawing Room 30 The Exit Passage 37 The Clive Museum 38 The Staircase 38 The Ballroom 41 Acknowledgements 48 2 Above Thomas Gainsborough RA, c.1763 Edward Clive, 1st Earl of Powis III as a Boy See page 13 3 Introduction Occupying a grand situation, high up on One of the most notable features of a rocky prominence, Powis Castle began the collection is the impressive run of life as a 13th-century fortress for the family portraits, which account for nearly Welsh prince, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn. three-quarters of the paintings on display. However, its present incarnation dates From the earliest, depicting William from the 1530s, when Edward Grey, Lord Herbert and his wife Eleanor in 1595, Powis, took possession of the site and to the most recent, showing Christian began a major rebuilding programme. Herbert in 1977, these images not only The castle he created soon became help us to explore and understand regarded as the most imposing noble very intimate personal stories, but also residence in North and Central Wales. speak eloquently of changing tastes in In 1578, the castle was leased to Sir fashion and material culture over an Edward Herbert, the second son of extraordinarily long timespan.