Tunisia's Endangered Exception: History at Large in the Southern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ennahda's Approach to Tunisia's Constitution

BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER ANALYSIS PAPER Number 10, February 2014 CONVINCE, COERCE, OR COMPROMISE? ENNAHDA’S APPROACH TO TUNISIA’S CONSTITUTION MONICA L. MARKS B ROOKINGS The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high- quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its scholars. Copyright © 2014 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha TABLE OF C ONN T E T S I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................1 II. Introduction ......................................................................................................................3 III. Diverging Assessments .................................................................................................4 IV. Ennahda as an “Army?” ..............................................................................................8 V. Ennahda’s Introspection .................................................................................................11 VI. Challenges of Transition ................................................................................................13 -

Tunisia Transition Initiative (Tti) Final Report

TUNISIA TRANSITION INITIATIVE (TTI) FINAL REPORT MAY 2011 – JULY 2014 JULY 2014 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. 1 TUNISIA TRANSITION INITIATIVE (TTI) FINAL REPORT Program Title: Tunisia Transition Initiative (TTI) Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/OTI Washington Contract Number: DOT-I-00-08-00035-00/AID-OAA-TO-11-00032 Contractor: DAI Date of Publication: July 2014 Author: DAI The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TUNISIA TRANSITION INITIATIVE (TTI) CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................... 3 PROGRAM DESCRIPTION ............................................................ 3 PROGRAM OBJECTIVES ............................................................. 4 RESULTS .................................................................................. 4 COUNTRY CONTEXT ........................................................................ 6 TIMELINE .................................................................................. 6 2011 ELECTIONS AND AFTERMATH ............................................ 7 RISE OF VIOLENT EXTREMISM, POLITICAL INSTABILITY AND ECONOMIC CRISES ..................................................................................... 8 STAGNATION -

The Rise of Abir Moussi

The Counterrevolution Gains Momentum in Tunisia: The Rise of Abir Moussi Anne Wolf November 2020 SNAPSHOT SUMMARY • Abir Moussi, a ruling party official in the Ben Ali dictatorship and now an opposition leader in parliament, is making headlines in Tunisia on almost a daily basis with her anti-revolution stance and uncompromising positions. • Though elected only in October 2019, Moussi has since emerged as one of Tunisia’s most controversial, and influential, politicians. Her Free Destourian Party (PDL) is leading in public opinion polls, even though it currently holds just 17 out of 217 parliamentary seats. • Moussi not only openly defends many aspects of the dictatorship, she denies that a revolution even took place in 2011. She advocates banning the Ennahda Party and backs other illiberal policies. Moussi’s speeches are provocative, if not outright defamatory, and her sit-ins regularly paralyze parliament. • At a time when broad sections of Tunisian society feel disenchanted by persistent unemployment, governance gridlock, and insecurity, Moussi’s populist anti-revolution rhetoric is gaining ground. INTRODUCTION People (ARP) only in October 2019, Moussi has since emerged as one of Tunisia’s most Her speeches are provocative, slanderous, influential and widely followed politicians. Her if not outright defamatory. Abir Moussi, a Free Destourian Party (PDL) is now leading in former official in the Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali public opinion polls, even though it currently dictatorship and now an opposition leader in holds just 17 out of 217 parliamentary seats. parliament, is making headlines in Tunisia One recent poll placed the PDL’s support base on almost a daily basis. -

The Economic Agendas of Islamic Parties in Tunisia and Morocco: Between Discourses and Practices Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies Vol

Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies Vol. 11, No. 3, 2017 Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies Vol. 11, No. 3, 2017 The Economic Agendas of Islamists in Tunisia and Morocco: Between Discourse and Practices particular at two policy sectors whose drivers were both among the main demands raised during the uprisings, and fundamental pillars of Islamists’ political offer: The Economic Agendas of Islamic Parties in Tunisia employment/labour market and good governance/corruption. The article will try to address the following questions: what socioeconomic demands raised during the revolution have and Morocco: Between Discourses and Practices been successfully translated into viable political agendas by these two Islamist parties? Also, how have contingent and structural factors been shaping Islamists’ policies? Giulia CIMINI ķ By highlighting the similarities and the differences in the two case studies, the scope (Department of Humanity and Social Sciences, University of Naples L’Orientale, of this article is to reflect on the way the two Islamist parties have channeled mass support Italy) for the goals of the revolution into an institutionalized political consensus, as well as on the way they funnel and satisfy bottom-up interests and priorities, thus understanding to what extent these political parties are acting as stabilizing or destabilizing forces. Moreover, by Abstract: Six years since the so called “Arab Spring”, this article looks at the two Islamist looking at their platforms and policies, this article aims at analysing the gap between ruling parties that have since then – although under different circumstances - been key political Islamists parties’ discourses and practices in order to assess whether the interplay of other political and social actors had an impact on their ideological perspectives and the ongoing actors both in Tunisia and Morocco, respectively. -

Equal Citizenship in Tunisia: Constitutional Guarantees for Equality Between Citizens

Equal Citizenship in Tunisia: Constitutional Guarantees for Equality between Citizens By Salwa Hamrouni With the assistance of Nidhal Mekki September 2012 Table of Contents Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………… 1 I. Introduction …………………………………………………………………… 3 II. Methodology …………………………………………………………………… 3 III. Conclusions and Proposals ……………………………………………………. 4 IV. The Report ……………………………………………………………………... 6 1. Equality in Citizenship and Gendering of Legal Parlance ………………… 10 A. Comparative Constitutions …………………………………………….. 10 B. National Constitutional Proposals ……………………………………... 10 C. Recommendation ……………………………………………………… 13 2. Equality in Citizenship and the Enunciation of the Principle of Non- Discrimination ………………………………………………………… 14 A. Comparative Constitutions …………………………………………….. 14 B. National Constitutional Proposals …………………………………….. 16 C. Recommendation ……………………………………………………… 19 3. Equality in Rights and Duties in the Political Sphere ……………………… 21 A. Comparative Constitutions …………………………………………….. 21 B. National Constitutional Proposals ……………………………………… 22 C. Recommendation ……………………………………………………….. 25 4. Equality in Rights and Duties in Economic, Social, and Cultural Spheres …26 A. Comparative Constitutions ……………………………………………… 26 B. National Constitutional Proposals ………………………………………..27 C. Recommendation …………………………………………………………30 5. Equality in Citizenship and Family Life ………………………………………31 A. Comparative Constitutions ……………………………………………….31 B. National Constitutional Proposals ………………………………………..32 C. Recommendation ………………………………………………………… -

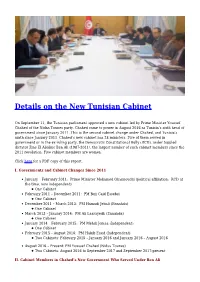

Details on the New Tunisian Cabinet

Details on the New Tunisian Cabinet On September 11, the Tunisian parliament approved a new cabinet led by Prime Minister Youssef Chahed of the Nidaa Tounes party. Chahed came to power in August 2016 as Tunisia’s sixth head of government since January 2011. This is the second cabinet change under Chahed, and Tunisia’s ninth since January 2011. Chahed’s new cabinet has 28 ministers. Five of them served in government or in the ex-ruling party, the Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD), under toppled dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali (1987-2011), the largest number of such cabinet members since the 2011 revolution. Five cabinet members are women. Click here for a PDF copy of this report. I. Governments and Cabinet Changes Since 2011 January – February 2011: Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi (political affiliation: RCD at the time, now independent) One Cabinet February 2011 – December 2011: PM Beji Caid Essebsi One Cabinet December 2011 – March 2013: PM Hamadi Jebali (Ennahda) One Cabinet March 2013 – January 2014: PM Ali Laarayedh (Ennahda) One Cabinet January 2014 – February 2015: PM Mehdi Jomaa (Independent) One Cabinet February 2015 – August 2016: PM Habib Essid (Independent) Two Cabinets: February 2015 – January 2016 and January 2016 – August 2016 August 2016 – Present: PM Youssef Chahed (Nidaa Tounes) Two Cabinets: August 2016 to September 2017 and September 2017-present II. Cabinet Members in Chahed’s New Government Who Served Under Ben Ali Radhouane Ayara – Minister of Transportation Political affiliation: Nidaa Tounes New position, -

The Tunisian Revolution in Its Constitutional Manifestations the First Transitional Period (14 January 2011 - 16 December 2011)

The Tunisian Revolution in its constitutional manifestations The first transitional period (14 January 2011 - 16 December 2011) Yadh BEN ACHOUR Revolution is, from the legal analysis standpoint, an exceptional event for the existing constitutional framework in a particular country. Its consequences are either limited to the overthrow of the powers operating under the Constitution, or encompass the entire constitutional order, leading to its abolition and then replacement with a new constitutional system. What matters in a revolution is the emergence of the future's legitimacy from the phenomenon of “illegitimacy.” If we assume, in general terms, that a revolution “is not governed by the normal standards of political rationality” and its identity stems from the logic of explosion or the logic of the volcano1 - this fact would a fortiori be dominant in the legal field. For this reason, some theorists of the positivist school determined that the revolutionary phenomenon cannot in any way be subject to legal analysis. Even if the effect of the revolution is clear with regard to constitutional legitimacy as it breaches its provisions or totally revokes it, it cannot invalidate the entire legislative system. This system will remain valid, except for the abrogated or amended provisions of the texts that govern it. The revolution impacts the constitutional order much more strongly than it impacts the legislative system. In revolutions, the constitutional order often breaks down, partially or completely, and the legislative system survives with its institutions, except the part of it that is revoked or amended, as in the case of Tunisia. A revolution is a historic moment with deep consequences. -

Mapping of the Arab Left Contemporary Leftist Politics in the Arab East

Edited by: Jamil Hilal and Katja Hermann MAPPING OF THE ARAB LEFT Contemporary Leftist Politics in the Arab East 2014 MAPPING OF THE ARAB LEFT Contemporary Leftist Politics in the Arab East Edited by Jamil Hilal and Katja Hermann 2014 The production of this publication has been supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Regional Office Palestine. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Regional Office Palestine. Translation into English: Ubab Murad (with the exception of the text on Iraq). Turbo Design TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .............................................................................................................6 Introduction: On the Self-definition of the Left in the Arab East ...................8 The Palestinian Left: Realities and Challenges ..............................................34 The Jordanian Left: Today’s Realities and Future Prospects .........................56 The Lebanese Left: The Possibility of the Impossible ....................................82 An Analysis of the Realities of the Syrian Left ............................................102 The Palestinian Left in Israel .........................................................................126 The Iraqi Left: Between the Shadows of the Past and New Alliances for a Secular Civic State .................................................................................148 MAPPING OF THE ARAB LEFT Contemporary -

Faculty of Law, Social and Political Sciences, Carthage University Master's Degree in Democratic Governance Democracy and Huma

Faculty of Law, Social and Political Sciences, Carthage University Master’s Degree in Democratic Governance Democracy and Human Rights in the Middle East and North Africa A.Y. 2016/2017 Ennahda’s Democratic Islam: Between Pragmatism AND Neo-Political Islam Thesis EIUC GC DE.MA Author: Yasmine Jamal Hajar Supervisor: Dr. Chaker Mzoughy Declaration I, Yasmine Hajar, declare that this thesis is a result of my research, investigations, and findings. Sources of information other than my own have been acknowledged and a reference list has been added to the appendix. This work has not been previously submitted to any other university for award of any type of academic degree. Date: 18 June 2017 Signature: YASMINE JAMAL HAJAR 1 Abstract Recently, the Tunisian Islamist party Ennahda has announced a break up with Political Islam and the start of new phase of Democratic Islam (al-Islām al-dimuqrāṭī). This study is questioning the emerged concept of Democratic Islam. Making use of primary and secondary materials, the author will indulge in the history of Ennahda with focus on the political shifts the party has undertaken since its initiation in the early seventies. The author will also analyze the political attitude of the party in the context of post-revolution. This study could be described as a comparative one as it will include a comparison of Ennahda’s ideological thoughts with the authentic thoughts of the Ikhwani ideologues, Hasan Al-Banna and Sayyed Qutb, to analyze the changes that have been conducted by the party under its new claimed ideology. The purpose of this study is to show whether the step undertaken by Ennahda through adopting the so-called Democratic Islam is a sign of neo-political Islam or it is just a pragmatic step taken by Ennahda to yield itself to realpolitik, aiming at consolidating itself in power and not to repeat the years of political exclusion under Bourguiba and Bin Ali. -

Major Political Parties Coverage for Data Collection 2021 Country Major

Major political parties Coverage for data collection 2021 Country Major political parties EU Member States Christian Democratic and Flemish (Chrétiens-démocrates et flamands/Christen-Democratisch Belgium en Vlaams/Christlich-Demokratisch und Flämisch) Socialist Party (Parti Socialiste/Socialistische Partij/Sozialistische Partei) Forward (Vooruit) Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats (Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten) Reformist Movement (Mouvement Réformateur) New Flemish Alliance (Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie) Ecolo Flemish Interest (Vlaams Belang) Workers' Party of Belgium (Partij van de Arbeid van België) Green Party (Groen) Bulgaria Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (Grazhdani za evropeysko razvitie na Balgariya) Bulgarian Socialist Party (Bulgarska sotsialisticheska partiya) Movement for Rights and Freedoms (Dvizhenie za prava i svobodi) There is such people (Ima takav narod) Yes Bulgaria ! (Da Bulgaria!) Czech Republic Mayors and Independents STAN (Starostové a nezávislí) Czech Social Democratic Party (Ceská strana sociálne demokratická) ANO 2011 Okamura, SPD) Denmark Liberal Party (Venstre) Social Democrats (Socialdemokraterne/Socialdemokratiet) Danish People's Party (Dansk Folkeparti) Unity List-Red Green Alliance (Enhedslisten) Danish Social Liberal Party (Radikale Venstre) Socialist People's Party (Socialistisk Folkeparti) Conservative People's Party (Det Konservative Folkeparti) Germany Christian-Democratic Union of Germany (Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands) Christian Social Union in Bavaria (Christlich-Soziale -

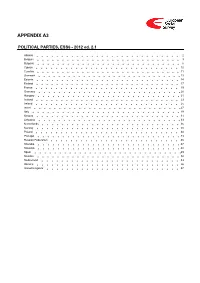

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

Islamic Political Party Formation in Morocco, Turkey and Jordan A

Between Movement and Party: Islamic Political Party Formation in Morocco, Turkey and Jordan A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Esen Kirdi! IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Samuels Kathleen Collins July 2011 © Esen Kirdi! 2011 Acknowledgements I could have not written this dissertation without the intellectual, material and moral support of many people. I am indebted to all of them. In what follows, I will attempt the impossible task of acknowledging them all in a limited space such as this. As a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, I had the great opportunity to be a part of an intellectual community composed of a number of remarkable scholars and colleagues. I feel especially privileged and honored to have the chance to work closely with, and be mentored by, two wonderful advisors, David Samuels and Kathleen Collins. David Samuels’ Political Parties and Party Systems seminar played a central role in the framing of this project. It was in this seminar, I started researching about Islamic political parties. If David had not encouraged me to take the project further, this project would have remained as a seminar paper. I also thank David for his generosity with his time in commenting on multiple drafts of each chapter of this dissertation, his quick draft turnovers and patient replies to all my questions. David’s thoughtful comments and incisive criticisms urged me to see the bigger picture, and in doing so, helped me to express my thoughts more clearly.