Adposition and Case Supersenses V2.5: Guidelines for English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

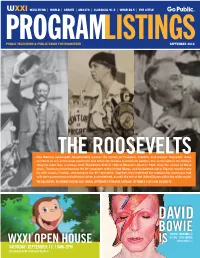

Program Listings” Christopher C

WXXI-TV/HD | WORLD | CREATE | AM1370 | CLASSICAL 91.5 | WRUR 88.5 | THE LITTLE PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSSEPTEMBER 2014 Ken Burns’s seven-part documentary weaves the stories of Theodore, Franklin, and Eleanor Roosevelt, three members of one of the most prominent and influential families in American politics. The series follows the family’s story for more than a century, from Theodore’s birth in 1858 to Eleanor’s death in 1962. Over the course of those years, Theodore would become the 26th president of the United States, and his beloved niece, Eleanor, would marry his fifth cousin, Franklin, who became the 32nd president. Together, they redefined the relationship Americans had with their government and with each other, and redefined, as well, the role of the United States within the wider world. THE ROOSEVELTS: AN INTIMatE HISTORY AIRS SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 14 THROUGH SatURDAY, SEPTEMBER 20 at 8 P.M. ON WXXI-TV TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 23 at 7 P.M. LITTLE THEatrE DEtaiLS INSIDE >> SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 10AM-2PM SEE INSIDE FRONT COVER FOR DEtaiLS! DEAR FRIENDS, EXECUTIVE StaFF SEPTEMBER 2014 No rm Silverstein, President VOLUME 5, ISSUE 9 Susan Rogers, Executive Vice President and General Manager This month marks the premiere of WXXI is a public non-commercial Je anne E. Fisher, Vice President, Radio broadcasting station owned the much-anticipated documentary Kent Hatfield, Vice President, Technology and Operations and operated by WXXI Public series on the Roosevelts by Ken Broadcasting Council, a not-for- El issa Orlando, Senior Vice President of TV and News Burns, America’s most acclaimed profit corporation chartered by the Board of Regents of New BOARD OF TRUSTEES OFFICERS filmmaker. -

Logik Des Filmischen. Wissen in Bewegten Bildern 2011

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Philipp Blum; Sven Stollfuß Logik des Filmischen. Wissen in bewegten Bildern 2011 https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2011.3.185 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Blum, Philipp; Stollfuß, Sven: Logik des Filmischen. Wissen in bewegten Bildern. In: MEDIENwissenschaft: Rezensionen | Reviews, Jg. 28 (2011), Nr. 3, S. 294–312. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2011.3.185. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Church Tomorrow^ 9:45 A.M

___ X MONDAY, APRIL 6, 1969 Bloodmobile Visits Center Church Tomorrow^ 9:45 a.m. to 2:30p.m. #AC«''roiJRTEiEN iJIattrlfjPBtpr lEttfiting ijwalb Mystic Review, WBA members, The Weather John Mather Chapter, Order of Th# Adult inquiry and Informa PRESCRIPTIONS .Average Daily Net Pre.a» Run DeMolay, will confer the Initiatory tion group will meet Wednesday at will meet tomorrow at 8 p>m. for Busy Meeting SEC Claims Guterma Firm ForeMMt ot 0. 8. Weather BarMU their buaineas mrtting in Odd Fel DAT OR NIGHT For the Week Ending About Town Depree upon a cIm s of candidate* ,7130 in Zion Lutheran Church, and April 4th, 1959 the Sunday school staff at 7:30. low* hall. Prealdent Irene La- BY EXPERTS tilondy, not so eold tonight. l**r ______ at 7:30 thl* evening in the Ma*pn‘ Palme and Mrs. Ullian Demeusy Got Debentures for Nothing Richard N. Johnaoil. eon of Mr*. | Ic Temple. All Set Tonight .85-40. 88 edneaday, mnetly elondy The Missionary Sewing Group of will, aerve as co-chairmen of the ARTHUR DRU6 \ A cnw O. Johnson, 88 Linnmore to attend the biislnc** m^etlni^ refreshment committee. Members 12,905 with ahowers, eonttnued mild. ^ 7 a on the honor roll for the land officers are requested to be the Covenant Congregational ____ channeled through the Swiss iianrh^fitpr lEupmng fc a lh Church will meet thla evening at 8 may also bring articles for the For Planners The Securities and Exchangef many Member of the Audit High near 00. woond term at State Technical'present at «. -

Appendix Screenings and Additional Resources

Appendix Screenings and Additional Resources The analyses of various films and television programmes undertaken in this book are intended to function ‘interactively’ with screenings of the films and programmes. To this end, a complete list of works to accompany each chapter is provided below. Certain of these works are available from national and international distribution companies. Specific locations in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia for each of the listed works are, nevertheless, provided below. The entries include running time and format (16 mm, VHS, or DVD) for each work. (Please note: In certain countries films require copyright clearance for public screening.) Also included below are further or additional screenings of works not analysed or referred to in each chapter. This information is supplemented by suggested further reading. 1 ‘Believe me, I’m of the world’: documentary representation Further reading Corner, J. ‘Civic visions: forms of documentary’ in J. Corner, Television Form and Public Address (London: Edward Arnold, 1995). Corner, J. ‘Television, documentary and the category of the aesthetic’, Screen, 44, 1 (2003) 92–100. Nichols, B. Blurred Boundaries: Questions of Meaning in Contemporary Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994). Renov, M. ‘Toward a poetics of documentary’ in M. Renov (ed.), Theorizing Documentary (New York: Routledge, 1993). 2 Men with movie cameras: Flaherty and Grierson Nanook of the North, Robert Flaherty, 1922. 55 min. (Alternative title: Nanook of the North: A Story -

Big Al Free Trial

FREE BIG AL PDF Andrew Clements,"Yoshi" | 32 pages | 01 Nov 1997 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9780689817229 | English | New York, United States Big Al's Silicon Valley | Bowling, Arcade, Sports Bar, and Events He loves to sit in front of his cave and sing. He was resident bard and balladeer in the swamp before Walt Disney World was built and three badgers and an alligator have expressed great joy that he is now singing for people. Big Al appears during the ending of the show, singing "Blood on the Saddle" and threatening the Big Al of the show in the process. The other bears start bringing their singing together to counter Al's off-key crooning and eventually drive him off stage. In these versions of the show, the other bears don't seem to have much of a problem with him performing, since they actually let him take part in the finale and sing. Responding to a letter from Goofy asking if they can make some cheap fuel out of moonshine, Al has offered him a few batches while warning him that it Big Al been tested for machines and can pack a wallop. Big Al's is an outdoor gift-shop found in the Frontierland of the Magic Kingdom. Big Al appears on the shop's sign as the spokesperson for the shop which predominately sells plushies and Davy Crockett -style coonskin caps. He also appears in the parks as a walk-around character along with fellow Country Bears WendellShakerand Liver Lips. When performing all the way through autumn and missing an opportunity to find a place to hibernate, Big Al travels south and performs to earn money for food, but ends up frightening the locals and jumps aboard a truck. -

Analysis of Coastal Erosion on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts: a Paraglacial Island Denise M

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 January 2008 Analysis of Coastal Erosion on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts: a Paraglacial Island Denise M. Brouillette-jacobson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Brouillette-jacobson, Denise M., "Analysis of Coastal Erosion on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts: a aP raglacial Island" (2008). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 176. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/176 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANALYSIS OF COASTAL EROSION ON MARTHA’S VINEYARD, MASSACHUSETTS: A PARAGLACIAL ISLAND A Thesis Presented by DENISE BROUILLETTE-JACOBSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE September 2008 Natural Resources Conservation © Copyright by Denise Brouillette-Jacobson 2008 All Rights Reserved ANALYSIS OF COASTAL EROSION ON MARTHA’S VINEYARD, MASSACHUSETTS: A PARAGLACIAL ISLAND A Thesis Presented by DENISE BROUILLETTE-JACOBSON Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________ John T. Finn, Chair ____________________________________ Robin Harrington, Member ____________________________________ John Gerber, Member __________________________________________ Paul Fisette, Department Head, Department of Natural Resources Conservation DEDICATION All I can think about as I write this dedication to my loved ones is the song by The Shirelles called “Dedicated to the One I Love.” Only in this case there is more than one love. -

Gradivo, Kupljeno S Sredstvi MK SEPTEMBER – OKTOBER 2015

Gradivo, kupljeno s sredstvi MK SEPTEMBER – OKTOBER 2015 1. AMERICAN sniper [Videoposnetek] = Ostrostrelec / directed and produced by Clint Eastwood ; written by Jason Hall ; based on the book by Chris Kyle with Scott McEwen and Jim DeFelice ; director of photography Tom Stern ; produced by Robert Lorenz, Andrew Lazar, Bradley Cooper ... [et al.]. - [Ljubljana : Menart Records], [2015], p 2014. - 1 video DVD (127 min, 13 sek) : barve, zvok (Dolby Digital 5.1, 2.0) ; 12 cm Podnapisi v: angl., bolgar., est., hrv., latv., lit., polj., rus., slov., tur. in ukraj. Sinhronizacija v: angl., polj., rus., tur. in ukraj. Dialogi (v orig.) v angl., delno tudi v arab. - Posneto 2014. - Dvoslojni format. - DVDWB0792 [na ov.]. - 7000064595 / SP-12-DIM1 / DVD9 / Z26/Z29 / Y33673 26 12 [na DVD-ju]. - Igrajo: Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Luke Grimes, Jake McDorman, Cory Hardrict, Kevin Lacz, Keir O'Donnell, Kyle Gallner, Ben Reed, Elise Robertson, Marnette Patterson, Billy Miller itd. - Za odrasle. - Oskar, 2015 (najboljša montaža zvoka) a) Kyle, Chris (1974-2013) - Biografski filmi - Video DVD-ji b) Ameriški igrani filmi - Filmska drama - Video DVD-ji c) drama d) akcijski film e) biografski film f) vojni film g) triler h) thriller i) ameriški vojaki j) ostrostrelci k) Irak 791.221.4(73)(086.82) COBISS.SI-ID 1108339038 2. ANDREWS, Mary Kay, 1954- Pomladna vročica / Mary Kay Andrews ; [prevedla Katja Benevol Gabrijelčič]. - 1. izd. - Tržič : Učila International, 2015 (natisnjeno v EU). - 431 str. ; 20 cm Prevod dela: Spring fever. - Tisk po naročilu ISBN 978-961-00-2732-4 (trda vezava) ISBN 978-961-00-2733-1 (broš.) 821.111(73)-311.2 COBISS.SI-ID 281143808 3. -

Tom Parker Editor Avid, FCP, Online

Agent: Bhavinee Mistry [email protected] 020 7199 3852 Tom Parker Editor Avid, FCP, Online Education BA (Hons) American Studies and Politics, Keele University. 1999 Documentary World’s Deadliest Wrecks Mallinson Saddler Productions National 60 min Documentary Geographic Archive series looking at the story of WW2’s sunken battleships. Director: Mike Taylor, Series Producer: Michael Wadding, Executive Producer: Crispin Sadler, Commissioner: Helen Hawken The Ganges: India’s Great River Rare TV Channel 5 60 min Documentary Archive documentary following Anita Rani as she travels remotely along the Ganges. Director: Luc Tremoulet, Series Producer: Owen Rodd, Executive Producer: Rory Wheeler, Commissioner: Lucy Willis See No Evil Arrow Media Discovery ID 60 min Documentary Formatted documentary looking at how surveillance uncovers America’s deadliest crimes. Director: Tristan Goodley, Series Producer: John Owens, Executive Producer: Lucie Ridout, Commissioner: Tim Baney Gold Rush: Dave Turin’s Lost Mine Raw TV Discovery 60 min Observational Documentary Gold miner Dave Turin, previously featured in Gold Rush, visits 8 disused gold mines around the Western United States and decides which mine to get up and running to turn it into a profitable, working mine. Director: Judd Myles, Series Producers: Peter Campion and Rob Rawlings, Executive Producer: Sam Maynard, Commissioner: John Slaughter Keeping London Moving: Then and Now Blast Films Channel 5 2 x 60 min Factual Documentary, Additional Editor The London Underground was first dreamed up in the 1860s. This is the story of building London’s iconic transport system. Director: Mike Wadding, Executive Producer: Alistair Pegg, Commissioner: Guy Davies American Aristocrat Nutshell TV Smithsonian 2 x 60 min Observational Documentary This series goes behind the scenes of Britain’s most prestigious stately homes. -

Digital China: Powering the Economy to Global

DIGITAL CHINA: POWERING THE ECONOMY TO GLOBAL COMPETITIVENESS DECEMBER 2017 AboutSince itsMGI founding in 1990, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) has sought to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. As the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, MGI aims to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. The Lauder Institute at the University of Pennsylvania has ranked MGI the world’s number- one private-sector think tank in its Think Tank Index. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth, natural resources, labor markets, the evolution of global financial markets, the economic impact of technology and innovation, and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed the digital economy, the impact of AI and automation on employment, income inequality, the productivity puzzle, the economic benefits of tackling gender inequality, a new era of global competition, Chinese innovation, and digital and financial globalization. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company senior partners: Jacques Bughin, Jonathan Woetzel, and James Manyika, who also serves as the chairman of MGI. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, Anu Madgavkar, Sree Ramaswamy, and Jaana Remes are MGI partners, and Jan Mischke and Jeongmin Seong are MGI senior fellows. -

Documentary Screens: Non-Fiction Film and Television

Documentary Screens Non-Fiction Film and Television Keith Beattie 0333_74117X_01_preiv.qxd 2/19/04 8:59 PM Page i Documentary Screens This page intentionally left blank 0333_74117X_01_preiv.qxd 2/19/04 8:59 PM Page iii Documentary Screens Non-Fiction Film and Television Keith Beattie 0333_74117X_01_preiv.qxd 2/19/04 8:59 PM Page iv © Keith Beattie 2004 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2004 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 0–333–74116–1 hardback ISBN 0–333–74117–X paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

BBC R&D Annual Review 2001-2002

BBC Research & Development maintains a world-class forward research programme. This enables us to deliver significant competitive advantage to the BBC. BBC R&D ANNUAL REVIEW 1 foreword BBC Research & Development maintains a world-class forward research production systems, and the planning of a their roll-out across the BBC. Our R&D expertise programme in a variety of broadcast technologies. As a consequence we are is placing the BBC at the leading edge of this revolution – offering us a major efficiency advantage compared with our competitors. BBC Technology is implementing these pilot able to deliver significant competitive advantage to the BBC. This last year systems, and will themselves gain an important time advantage in reaching the market with has been particularly productive and fruitful. this key new technology. BBC R&D has also delivered leading-edge technology to support the BBC’s production The full benefits of digital broadcasting are now beginning to come through to our viewers function. Examples include our work on the new production centres, speech-assisted and listeners. The BBC has launched new television and radio services and significantly subtitling, high-definition video production, digital radio cameras, and virtual production. enhanced the quality and sophistication of the interactive and enhanced services on the In a time of rapid technology change, there is no shortage of demand from our BBC FOREWORD digital platform. Interactive Wimbledon 2001, the enhanced Walking with Beasts colleagues for our effort and advice. Demand exceeds our ability to meet it, and we have to programme, the BBC i-Bar, regional news programmes and the new BBC Children’s work hard to retain a significant allocation of effort to continue the long-term, blue-sky channels have all been critical successes for the BBC.