Documentary Screens: Non-Fiction Film and Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communism and the Portrayal of the Working Class at the National Film Board of Canada, 1939-1946

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2007 Filming politics: communism and the portrayal of the working class at the National Film Board of Canada, 1939-1946 Khouri, Malek University of Calgary Press Khouri, M. "Filming politics: communism and the portrayal of the working class at the National Film Board of Canada, 1939-1946". Series: Cinemas off centre series; 1912-3094: No. 1. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2007. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49340 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com FILMING POLITICS: COMMUNISM AND THE PORTRAYAL OF THE WORKING CLASS AT THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA, 1939–46 by Malek Khouri ISBN 978-1-55238-670-5 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

THE DOCUMENTARY IMAGINATION an Investigation by Video Practice Into the Performative Application of Documentary Film in Scholarship

THE DOCUMENTARY IMAGINATION An investigation by video practice into the performative application of documentary film in scholarship Trevor William Hearing A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 Bournemouth University This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. II ABSTRACT THE DOCUMENTARY IMAGINATION An investigation by video practice into the performative application of documentary film in scholarship The aim of the research has been to discover new ways in which documentary film might be developed as a performative academic research tool. In reviewing the literature I have acknowledged the well-established use of observational documentary film making in ethnography and visual anthropology underpinned by a positivist epistemology, but I suggest there are forms of reportage in literary and dramatic traditions as well as film that are more relevant to the possibility of an auto-ethnographic approach which applies documentary film in an evocative context. I have examined the newly emerging field of Performative Social Science and the "new subjectivity" evident in documentary film to investigate emerging opportunities to research and disseminate scholarly knowledge employing reflective documentary film methods in place of, or alongside, text. This inquiry has prompted me to consider the history of the creation and transmission of scholarship. The research methodology I have employed has been auto- ethnographic reflective film practice. -

A List of Australia's Big Things

A List of Australia's big Things Drawn from the Wikipedia article Australia's Big Things Australian Capital New South Wales Victoria Territory Western Australia South Australia Tasmania Northern Territory Australian Capital Territory Name Location Notes Located in the Belconnen Fresh Food Giant Markets, the Giant Mushroom shelters a Mushroom Belconnen children's playground. It was officially launched in 1998 by the ACT Chief Minister. Located at the main entrance to Giant Owl Belconnen town centre, the statue cost Belconnen $400,000 and was built by Melbourne sculptor Bruce Armstrong.[3] New South Wales Name Location Notes A bull ant sculpture designed by artist Pro Hart, which was erected in 1980 and originally stood at the Stephens Creek Hotel. It was moved to its current location, Big Ant Broken Hill next to the Tourist Information Centre in Broken Hill, after being donated to the city in 1990. Located in the middle of an orchard about 3km north of Batlow, without public Big Apple Batlow access. Only its top is visible from Batlow- Tumut Road, as it is largely blocked by apple trees. Big Apple Yerrinbool Visible from the Hume Highway Big Avocado Duranbah Located at Tropical Fruit World. Located alongside the Kew Visitor Information Centre. The original sculpture The Big Axe Kew was replaced in 2002 as a result of ant induced damage. This 1/40 scale model of Uluru was formerly an attraction at Leyland Brothers World, and now forms the roof of the Rock Restaurant. Technically not a "Big Big Ayers North Arm Cove Thing" (as it is substantially smaller than Rock the item it is modelled on), the Rock Restaurant is loosely grouped with the big things as an object of roadside art. -

For Release: on Approval Motion Picture Sound Editors to Honor

For Release: On Approval Motion Picture Sound Editors to Honor George Miller with Filmmaker Award 68th MPSE Golden Reel Awards to be held as a global, virtual event on April 16th Studio City, California – February 10, 2021 – The Motion Picture Sound Editors (MPSE) will honor Academy Award-winner George Miller with its annual Filmmaker Award. The Australian writer, director and producer is responsible for some of the most successful and beloved films of recent decades including Mad Max, Mad Max 2: Road Warrior, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome and Mad Max: Fury Road. In 2007, he won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature for the smash hit Happy Feet. He also earned Oscar nominations for Babe and Lorenzo’s Oil. Miller will be presented with the MPSE FilmmaKer Award at the 68th MPSE Golden Reel Awards, set for April 16th as an international virtual event. Miller is being honored for a career noteworthy for its incredibly broad scope and consistent excellence. “George Miller redefined the action genre through his Mad Max films, and he has been just as successful in bringing us such wonderfully different films as The Witches of Eastwick, Lorenzo’s Oil, Babe and Happy Feet,” said MPSE President MarK Lanza. “He represents the art of filmmaking at its best. We are proud to present him with MPSE’s highest honor.” Miller called the award “a lovely thing,” adding, “It’s a big pat on the back. I was originally drawn to film through the visual sense, but I learned to recognize sound, emphatically, as integral to the apprehension of the story. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

UX and Agile: a Bollywood Blockbuster Masala

UX and Agile: A Bollywood blockbuster masala Pradeep Joseph UXD Manager Juniper Networks Bangalore What is Bollywood? Wikipedia says: The name "Bollywood" is derived from Bombay (the former name for Mumbai) and Hollywood, the center of the American film industry. However, unlike Hollywood, Bollywood does not exist as a physical place. Bollywood films are mostly musicals, and are expected to contain catchy music in the form of song-and-dance numbers woven into the script. Indian audiences expect full value for their money. Songs and dances, love triangles, comedy and dare-devil thrills are all mixed up in a three-hour- long extravaganza with an intermission. Such movies are called masala films, after the Hindi word for a spice mixture. Like masalas, these movies are a mixture of many things such as action, comedy, romance and so on. Melodrama and romance are common ingredients to Bollywood films. They frequently employ formulaic ingredients such as star-crossed lovers and angry parents, love triangles, family ties, sacrifice, corrupt politicians, kidnappers, conniving villains, courtesans with hearts of gold, long-lost relatives and siblings separated by fate, dramatic reversals of fortune, and convenient coincidences. What has UX and Agile got to do with Bollywood? As a Designer I faced tremendous challenges while moving into an Agile environment. While drowning the sorrows with designers from other organizations I came to realize that they too face similar challenges. This inspired me to explore further into what makes designers sad, what makes them suck and what are the ways in which they can contribute more in an Agile environment. -

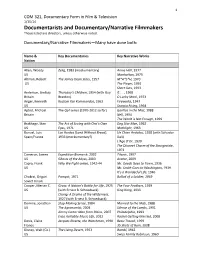

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

Parallax Historiography: the Flâneuse As Cyberfeminist Catherine Russell, Concordia University, Canada

Parallax Historiography: The Flâneuse as Cyberfeminist Catherine Russell, Concordia University, Canada "Cyborg imagery can suggest a way out of the maze of dualisms in which we have explained our bodies and our tools to ourselves. This is a dream not of a common language, but of a powerful infidel heteroglossia." Donna Haraway Haraway's cyborg manifesto may seem an odd choice of theoretical paradigms for developing insight into silent cinema; and yet I would like to suggest that new media technologies have created new theoretical "passages" back to the first decades of film history. The flâneuse, an imaginary construction of female subjectivity who is our guide in this journey, is herself a cyborg. She figures the relationship between women and technology as a mobile, fluid and productive means of, in Haraway's words, "building and destroying machines, identities, categories, relationships, spaces, stories" (1997: 482). Recent developments in film historiography by feminist theorists have shifted the emphasis from textual analysis of the woman onscreen to the invisible history of the spectator-subject. As Patrice Petro puts it, "In contrast to formalist film historians, who seek to recover what is increasingly becoming a lost object, feminists have been primarily concerned to unearth the history of the (found) female subject" (1990: 11). This is a discovery that calls for discourse drawn from the utopian genres of techno-feminism. That this "discovery" of female subjectivity has been motivated by the parallels between early cinema and new imaging technologies is, I believe, a fundamental aspect of the new feminist film historiography. The term "parallax" is useful to describe this historiography, because it is a term that invokes a shift in perspective as well as a sense of parallelism. -

The Rights of the Accused in Saudi Criminal Procedure

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 15 Number 4 Symposium: Business and Investment Law in the United States and Article 5 Mexico 6-1-1993 The Rights of the Accused in Saudi Criminal Procedure Jeffrey K. Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey K. Walker, The Rights of the Accused in Saudi Criminal Procedure, 15 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 863 (1993). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol15/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rights of the Accused in Saudi Criminal Procedure JEFFREY K. WALKER* I. INTRODUCTION In Islam, the only law is the law of God, and the law of God is the Shari'a. Literally "the way" or "the straight path," Shari'a is the civil and criminal law of Saudi Arabia2 and the Koran is the Saudi constitution. 3 "In Saudi Arabia, as in other Muslim countries, reli- gion and law are inseparable. Ethics, faith, jurisprudence, and practi- cality are so interdependent that it is impossible to study only Islamic religion or only Islamic law."' 4 Indeed, Islamic law is intended to serve as the expression of God's will. -

DNA Nation Press

PRESS KIT DISTRIBUTOR CONTACT PRODUCTION CONTACT SBS International Blackfella Films Lara von Ahlefeldt Darren Dale Tel: +61 2 9430 3240 Tel: +61 2 9380 4000 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 10 Cecil Street Paddington NSW 2021 Tel: +612 9380 4000 Fax: +612 9252 9577 Email: [email protected] www.blackfellafilms.com.au Production Notes Producer Darren Dale Producer & Writer Jacob Hickey Series Producer Bernice Toni Director Bruce Permezel Production Company Blackfella Films Genre Documentary Series Language English Aspect Ratio 16:9 FHA Duration EP 1 00:51:53:00 EP 2 00:54:54:00 EP 3 00:52:58:00 Sound Stereo Shooting Gauges Arri Amira, F55, DJI Inspire Drone, Blackmagic & Go Pro Logline Who are we? And where do we come from? Short Synopsis Who are we? And where do we come from? Australia’s greatest Olympian Ian Thorpe, iconic Indigenous actor Ernie Dingo, and TV presenter and Queen of Eurovision Julia Zemiro set off on an epic journey of genetic time travel to find out. © 2016 Blackfella Films Pty Ltd Page 2 of 40 Long Synopsis Who are we? And where do we come from? Australia’s greatest Olympian Ian Thorpe, iconic Indigenous actor Ernie Dingo, and TV presenter and Queen of Eurovision Julia Zemiro set off on an epic journey of genetic time travel to find out. DNA is the instruction manual that helps build and run our bodies. But scientific breakthroughs have discovered another remarkable use for it. DNA contains a series of genetic route maps. It means we can trace our mother’s mother’s mother and our father’s father’s father, and so on, back through tens of millennia, revealing how our ancestors migrated out of Africa and went on to populate the rest of the world. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld.