An Exhibition Celebrating Collaborative Craft And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WR 16Mar 1928 .Pdf

World -Radio, March 16, 1928. P n n rr rrr 1 itiol 111111 SPECIAL IRISHNUMBER Registered at the.G.P.O. Vol. VI.No. 138. as a Newspaper. FRIDAY. MARCH 16, 1928. Two Pence. WORLD -RADIO 8 tEMEN Station Identification Panel- Konigswusterhausen (Zeesen). Germany REC GE (Revised) Wavelength : 125o in. Frequency : 240 kc. Power :35 kw. H. T. BATTERY Approximate Distance from London : 575 miles. (Lea-melte Tide) Call " Achtung !Achtung !Hier die Deutsche Welle, Berlin,-Konigswus- terhausen."(Sometimes wavelength POSSESSES all the advantages of a DRY BATTERY given :" . auf Welle zwolf hun- dert and fiinfzig," when callre- -none of the disadvantages of the ordinary WET peated.)When relaying :" Ferner Ubertragimgauf "... (nameof BATTERY. relaying stations). Interval Signal:Metronome.Forty beats in ten seconds. 1. Perfectly noiseless, clean SpringConnections,no IntervalCall :" Achtung !Konigs. and reliable. 4.soldering. wusterhausen.DerVortragvon [name of lecturer]uber[titleof 5. No "creeping of salts. lecture]ist beendet.Auf Wieder- 2. Unspillable. Easily recharged, & main- 'toren in . Minuten."When 6. relaying :`& Auf Wiederhorenfur 3No attention required until tains full energy through- Konigswusterhausen in . exhausted. out the longest programme. Minuten ;fur Breslau and Gleiwitz [or as the case may be] nach eigenem Programm." 711,2 ails are null: in thefoll,n,ing three sizes: Own transmissionsandrelays.In eveningrelaysfromotherstations. H.T.1.Small ... 8d. each. Closes down at the same time as the relaying station. H.T.2.Large ... 10d. each. H.T.3.Extra Large 1:- each. (Copyright) A booklet containing alargenumberof these Guaranteed to give I a,volts per cell. panels canbeobtainedof B.B.C.Publications, Savoy Hrll, W. -

Tour Dates: 14Th May 2022 27Th August 2022 08Th October 2022

10 Night Aran Islands, Donegal & Causeway Coast Knitting Tour Tour Dates: 14th May 2022 27th August 2022 08th October 2022 Tour Overview Your 10 night knitting tour begins with a visit to Trinity College Library and the Book of Kells followed by a visit to the Constant Knitter Yarn Store where you will meet a local craftsperson for a short demonstration and informal discussion. On the second day of this tour, you will meet with Lisa Sisk for a workshop on the Moebius Knitting technique. The tour continues to the west of Ireland to Inis Mór, the largest of the Aran Islands. Here you will enjoy a cultural and traditional knitting and crafts experience with well known knitting instructor – Úna McDonagh. In County Mayo, we visit to the Museum of Country Life to meet with Ciara Ní Reachtnín for another workshop. The Northern part of this tour includes a visit to the magnificent Slieve League Cliffs, Studio Donegal – a hand-weaving and clothing manufacturing company, Glencolmcille Folk Village and a workshop with Irish designer, Edel MacBride. This tour takes you on a discovery of the Causeway Coast, the Giant’s Causeway and Dunluce Castle. In Belfast, a visit to the Titanic Belfast Visitor Experience is included as well as a trip outside Belfast to Mourne Alpacas. As we travel back to Dublin, we stop at the Irish Linen Centre in Lisburn for a guided tour and experience a spinning and tapestry workshop with Áine Dunne. Included in This Tour- • Transfers on arrival and departure by private coach (for arrivals prior to 10:30am on tour start date and departures on tour end date) • Sightseeing as per itinerary in a luxury coach with an experienced driver and accredited guide, entrance fees included if applicable. -

What's on A5 8Pp Booklet - Jul-Sep 2019 - Final.Qxp 11/06/2019 12:39 Page 1

Linen Hall Library - What's On A5 8pp Booklet - Jul-Sep 2019 - Final.qxp 11/06/2019 12:39 Page 1 Cover Image: From the Linenopolis Exhibition. Linen Hall Library - What's On A5 8pp Booklet - Jul-Sep 2019 - Final.qxp 11/06/2019 12:39 Page 2 July EXHIBITION PERFORMANCE The Weaver and the Factory Linenopolis Maid: Songs of the Linen Trade 1 July – 31 August • Free With Maurice Leyden and Jane Cassidy This exciting new exhibition will celebrate Belfast’s Thursday 4 July at 6pm • £8 linen heritage and the many businesses connected to the linen industry in Belfast’s Linen Quarter. Maurice Leyden and Jane Cassidy are a husband Examining social history, working life, family life and and wife team of folk singers and song collectors from the health of the workers, it includes items loaned Belfast, who have been performing Ulster songs for from PRONI, Coleraine Museum and linen over 30 years. Maurice has published two collections specialists McBurney and Black. Artists Anna Smyth, of traditional songs Belfast, City of Song (1989, Claire Mooney and Nathanael Smyth will showcase Brandon Press), and Boys and Girls Come Out to current work reflecting the influence and use of linen Play (1993, Appletree Press). He is currently working today. Photographs created as part of a community on his latest book in which he examines the social outreach project in partnership with Belfast Exposed history of the Ulster linen industry through folk song. will also be exhibited. This project has been funded by the Department for Communities, Tourism Northern Ireland and National LECTURE Lottery Heritage Fund as part of the European Year of Cultural Heritage. -

“Methinks I See Grim Slavery's Gorgon Form”: Abolitionism in Belfast, 1775

“Methinks I see grim Slavery’s Gorgon form”: Abolitionism in Belfast, 1775-1865 By Krysta Beggs-McCormick (BA Hons, MRes) Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) October 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words. Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………… I Illustration I …………………………………………………………………………...…… II Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………. III Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter One – “That horrible degradation of human nature”: Abolitionism in late eighteenth-century Belfast ……………………………………………….…………………………………………….. 22 Chapter Two – “Go ruthless Avarice”: Abolitionism in nineteenth century Georgian Belfast ………………………………………………………………………................................... 54 Chapter Three – “The atrocious system should come to an end”: Abolitionism in Early Victorian Belfast, 1837-1857 ……………………………………………………………... 99 Chapter Four - “Whether freedom or slavery should be the grand characteristic of the United States”: Belfast Abolitionism and the American Civil War……………………..………. 175 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………….. 206 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………………... 214 Appendix 1: Table ……………………………………………………………………….. 257 Appendix 2: Belfast Newspapers .…………….…………………………………………. 258 I Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the help and guidance of many people to whom I am greatly indebted. I owe my greatest thanks to my supervisory team: Professor -

Weaving Books and Monographs

Tuesday, September 10, 2002 Page: 1 ---. 10 Mujeres y Textil en 3d/10 Women and Textile Into 3. [Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. Galeria Aristos, 1975], 1975. ---. 10 Mujeres y Textil en 3d/10 Women and Textile Into 3. [Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. Galeria Aristos, 1975], 1975. ---. 100 Jahre J. Hecking; Buntspinnerei und Weberei. Wiesbaden, Verlag f?r Wirtschaftspublizistik Bartels, 1958. ---. 100 Years of Native American Arts: Six Washington Cultures. [Tacoma, Washington: Tacoma Art Museum, 1988], 1988. ---. 1000 [i.e. Mil] Años de Tejido en la Argentina: [Exposici?n] 24 de Mayo Al 18 Junio de 1978. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura y Educaci?n, Secretaría de Cultura, Instituto Nacional de Antropología, 1978. ---. 1000 Years of Art in Poland. [London, Great Britain: Royal Academy of Arts, 1970], 1970. ---. 101 Ways to Weave Better Cloth: Selected Articles of Proven Interest to Weavers Chosen from the Pages of Textile Industries. Atlanta, GA.: Textile Indistries, 1960. ---. 125 Jahre Mech. Baumwoll-Spinnerei und Weberei, Augsburg. [Augsburg, 1962. ---. 1977 HGA Education Directory. West Hartford, CT: Handweavers Guild of America, 1978. ---. 1982 Census of Manufactures. Preliminary Report Industry Series. Weaving Mills. [Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of, 1984. ---. 1987 Census of Manufactures. Industry Series. Weaving and Floor Covering Mills, Industries 2211, 2221, 2231, 2241, and 2273. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of, 1990. ---. 1987 Census of Manufactures. Preliminary Report. Industry Series. Weaving and Floor Covering Mills: Industries 2211, 2221, 2241, and 2273. [Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of, 1994. ---. 1992 Census of Manufactures. -

The Case of Belfast, Northern Ireland

MISCELLANEA GEOGRAPHICA – REGIONAL STUDIES ON DEVELOPMENT Vol. 19 • No. 2 • 2015 • pp. 5-8 • ISSN: 2084-6118 • DOI: 10.1515/mgrsd-2015-0002 Island cities: the case of Belfast, Northern Ireland Abstract The paper considers Belfast as an ‘island city’ with reference to issues Stephen A. Royle of identity and economy and especially in connection with a series of statements from the ‘Futures of Islands’ briefing document prepared for the IGU’s Commission on Islands meeting in Kraków in August 2014. Belfast as a contested space, a hybrid British/Irish city on the island of School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology Ireland, exemplifies well how ‘understandings of the past condition the Queen’s University Belfast future’, whilst the Belfast Agreement which brought the Northern Ireland United Kingdom peace process to its culmination after decades of violence known as the e-mail: [email protected] ‘Troubles’ speaks to ‘island ways of knowing, of comprehending problems – and their solutions’. Finally, Belfast certainly demonstrates that ‘island peoples shape their contested futures’. Keywords Island cities • Belfast • Northern Ireland • islands • peace process Received: 2 September 2014 © University of Warsaw – Faculty of Geography and Regional Studies Accepted: 10 March 2015 Island cities contested futures’. This paper seeks to find expression of such Are all cities situated on islands ‘island cities’? In a strict matters in the case of what will be argued is the ‘island city’ of geographical sense obviously they are, but if a set of criteria is Belfast, capital of Northern Ireland. established to define an ‘island city’, then only some cities on islands will have the necessary characteristics. -

Designer and Modernist

DESIGNER AND MODERNIST THE IMPACT AND INFLUENCE OF LINEN DESIGN ON THE WORK OF COLIN MIDDLETON One volume DICKON HALL School of Art and Design of Ulster University Ph.D. March 2019 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Abbreviations iv Timeline – 1870-1945 1946-1985 Introduction 1 Chapter One – Charles Collins Middleton 45 Chapter Two, Part One – John Hewitt 79 Chapter Two, Part Two – John Hewitt (continued) 112 Chapter Three – John Middleton Murry 149 Chapter Four – Victor Waddington 180 Chapter Five – Colin Middleton 220 Conclusion 263 Bibliography 272 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors, Professor Karen Fleming and Dr Joseph McBrinn, for their support, advice and encouragement throughout the research and writing of this PhD thesis, as well as Dr Justin Magee and many other staff at Ulster University for their guidance and assistance at every stage. I am very grateful to Kim Mawhinney for giving me such generous access to the Colin Middleton Archive held by NMNI and also to their collection of his works, and to her colleagues at the Ulster Museum, Anne Stewart, Anna Liesching and Mary Dornan, who have been so helpful. I would also like to acknowledge the Deputy Keeper of the Records, the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. Many other people have kindly assisted with my research in various ways and I would like to thank them and to apologise to any whom I have inadvertently left out: Nelson Bell, Terry Boyd, John Breakey, David Britton and Karen Reihill, Anne de Buck, Chris Caldwell, Professor Mike Catto, Dr Riann Coulter, David Foster, Dr Brian Kennedy, Sean Kissane, Dr Paul Larmour, David Lennon, Linda Logue, Emer Lynch, Eamonn Mallie, Charlie Minter, Shelagh Parkes, Dr Jackie Reilly, Alison Smith, Claire Walsh and Ian Whyte. -

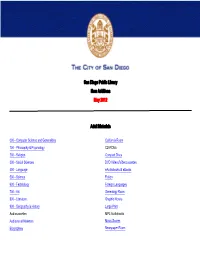

San Diego Public Library New Additions May 2012

San Diego Public Library New Additions May 2012 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes MP3 Audiobooks Audiovisual Materials Music Scores Biographies Newspaper Room Fiction Call # Author Title [MYST] FIC/ADAMS Adams, Jane Night vision : a Naomi Blake novel [MYST] FIC/ALLAN Allan, Barbara. Antiques disposal [MYST] FIC/ALLINGHAM Allingham, Margery Cargo of eagles [MYST] FIC/ALLINGHAM Allingham, Margery The mind readers [MYST] FIC/ATHERTON Atherton, Nancy. Aunt Dimity and the village witch [MYST] FIC/ATKINS Atkins, Ace. Robert B. Parker's lullaby : a Spenser novel [MYST] FIC/BASS Bass, Jefferson. The inquisitor's key [MYST] FIC/BRADBURY Bradbury, Ray Death is a lonely business [MYST] FIC/CAVENDER Cavender, Chris. Rest in pizza [MYST] FIC/CLARK Clark, Marcia. Guilt by degrees : a novel [MYST] FIC/DOHERTY Doherty, P. C. The Mysterium : a Hugh Corbett medieval mystery [MYST] FIC/DRYDEN Dryden, Alex. The blind spy : a novel [MYST] FIC/EDWARDSON Edwardson, Åke Sail of stone [MYST] FIC/GOLDENBAUM Goldenbaum, Sally. A fatal fleece : a seaside knitters mystery [MYST] FIC/GRABENSTEIN Grabenstein, Chris. Fun house [MYST] FIC/GRAVES Graves, Sarah. Dead level : a home repair is homicide mystery [MYST] FIC/GREAVES Greaves, Chuck. Hush money [MYST] FIC/HARRIS Harris, Charlaine. Deadlocked [MYST] FIC/HAYS Hays, Tony. The stolen bride [MYST] FIC/JOHNSON Johnson, Craig As the crow flies [MYST] FIC/KEILLOR Keillor, Garrison. -

Ars-Textrina-Papers-2005.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS ARS TEXTRINA INTERNATIONAL TEXTILES CONFERENCE JULY 21-22, 2005 FORM, MATERIALS AND PERFORMANCE A Selection of Papers Edited by B. G. Thomas The University of Leeds International Textiles Archive (ULITA), The University of Leeds, United Kingdom Copyright remains with the authors Contents Complex Geometric Patterning of Woven Fabrics by Incident Water Jets S. J. Russell, M. A. Hann and S. Sengupta 1 The Exquisite Linen of Beth Shean N. Ben-Yehuda 7 Affective Textile and Costume Museum Website Design F. S. Lin and T. Cassidy 15 Databank of Ornamental Woven Fabrics – The Lithuanian Experience J. Katunskis, V. Milasius and D. Taylor 22 How well can People Predict Subtractive Mixing? P. M. Henry and S. Westland 26 Southeast Asian Baskets: The Interface of Ethnobotany, Agriculture and Design V. Z. Rivers 32 Fabric Design Criteria for Reducing the Effect of Pilling in High Performance Fabrics M. Brookes, D. Brook and S. J. Russell 44 The History & Development of Bradford Industrial Museum and its Textile Collection E. Nicholson 50 The American Silk Crisis K. Dirks 53 Fleece - A World of Possibilities M. Goddard and D. Brook 64 Power, Pattern and Protection in Japanese Textiles M. Maule 68 Digital Printing – A 21st Century Paintbrush (Painting with Light, Colour and Image) R. Burton 71 Modern Education and Training for Textile Technologists and Managers A. Primentas 77 Conservation of the ‘Vane Tempest’ National Union of Mineworkers’ Banner J. Hyman 82 The Delaware Quilt Documentation Project: Piecing Together Delaware’s Quilting History F. W. Mayhew and J. A. Funderburk 85 i Development of Ornament Notation for Woven Fabrics - Our Approach V. -

Connswater Industrial Heritage Trail

CONNSWATER Industrial Heritage C RE OM TRAIL M C S Lewis Square E N E D C & EastSide Visitor I E R D P R L E Centre. Est 2016 I T A Irish Distillery Holywood Arches Bloomeld Bakery Belfast Ropeworks R.J Welch © Ulster Museum Belfast had its origins as a small settlement Belfast 440000 called Béal Feirste, at the mouth of the river Farset. Growth was slow - by 1700, its AN INDUSTRIAL POWERHOUSE 349000 440,000 > population was only 2,500. Yet 150 years later, 349,000 > after the Irish Famine, it mushroomed to over 100,000, as people moved from the country to the town in search of work. Thousands were employed in the rapidly growing linen mills, rope factories, engineering works and shipyards of east Belfast. Huge factories lined the 62500 banks of the Connswater, Knock and Loop rivers WATER STEAM ELECTRICITY and narrow horse-drawn barges, called lighters, 2000 1900 1800 brought raw materials and carried away nished 62,500 > goods for export. Water from1700 the rivers fed powerful steam engines and was used for many industrial processes. 1732 Belfast1752 Belfastgains its gains rst newspaperits rst1773 bank 17 million yards of linen1793 Shipbuildingexported begins1815 in 1823Belfast 1829 183918411843 1851 1862 1872 188818901895 1904 1906 1911 1936 1941 1966 1989 19941997 2000 Belfast gains a hospital Clarendon Dock is built The RMS Titanic is launched in Belfast Belfast gainsFirst steam gas Railwaylight drivenQueens toQueens spinning Lisburn Island Bridge millopensformed opensHarland &Horse Wol drawn ShipyardBelfast trams founded Albert runis madePublic inBridge Belfast a electricity city & Electric supply City trams Hall introduced opens ShortBelfast Brothers is bombed factory opensQueen ElizabethLaganside II BridgeLagan opens CorporationWaterfront Weir installed Odyssey formedHall opens opens Over the years, much of east Belfast’s industrial heritage has been lost, as factories and 18,000 > warehouses have been replaced by houses and Belfast Public Library built 13,000 > shops. -

Michelle Stephens

PERSPECTIVE: Michelle Stephens ‘There has always been a textile root in my family’ recalls Michelle Stephens, the Northern Irish born and trained artist. In the 1950s her father ‘used to draw patterns out for jacquard looms as well as creating the actual jacquard punch cards for a local mill.’ Like many artists growing up in Northern Ireland the history and legacy of the linen industry, a colossus of world-class technology and pioneering manufacturing in the early global marketplace, is hard to shake off even if it is now falling out of living memory. What Stephens has shaped from these familial and cultural memories is a sustained investigation into weaving as a craft that unifies conceptual art and precision-driven technology. Weaving’s unique algorithmic and computational resonance in our digital age, she suggests, can offer the artist as much as the designer a coded language that may be decoded and recoded in visual and material terms. Working off the loom and employing diverse material [as this sentence is shortened it should read ‘materials’] such as wood, metal, Perspex and paint as well as thread and deploying different techniques, from hand-weaving to steel forging and digital laser-cutting, Stephens desires to reanimate historic textiles not purely as a sort of aesthetic exercise and end in itself but as a means to draw attention to skill as a broadly-framed conceptual and technological exchange. The results can only really de described as constructed textile installations such as the recent Plain Weave or Basket Weave. By concentrating on their facture Stephens creates open-ended materialisations of the making process itself. -

Capital Cities Around the World This Page Intentionally Left Blank Capital Cities Around the World

Capital Cities around the World This page intentionally left blank Capital Cities around the World An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture ROMAN ADRIAN CYBRIWSKY Copyright 2013 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cybriwsky, Roman Adrian. Capital cities around the world : an encyclopedia of geography, history, and culture / Roman Adrian Cybriwsky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61069-247-2 (hardcopy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-61069-248-9 (ebook) 1. Cities and towns. 2. Capitals. I. Title. G140.C93 2013 909'.09732—dc23 2012046346 ISBN: 978-1-61069-247-2 EISBN: 978-1-61069-248-9 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America Contents List of Capital Cities vii List of Capital Cities by Country xiii Preface xix Introduction xxiii Capital Cities A-Z 1 Appendix: Selected Historic Capital Cities around the World 349 Selected Bibliography 357 Index 361 This page intentionally left blank List of Capital Cities Abu