Chapter 2: Bruckner’S Apprentice Years at St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dritten Reich" – Am Beispiel Des Musikwissenschaftlers Erich Schenk“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Musikgeschichte im "Dritten Reich" – am Beispiel des Musikwissenschaftlers Erich Schenk“ Verfasserin Anna Maria Pammer angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. Phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 312 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Diplomstudium Geschichte Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Friedrich Stadler INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. Einleitung 5 2. Erich Schenk zwischen Wissenschaft und Politik 13 2.1. Erich Schenk posthum 13 2.2. Erich Schenks Karriere als Musikwissenschaftler 14 EXKURS I: Adolf Sandberger oder Guido Adler? 25 I.1. Adolf Sandberger 25 I.2. Guido Adler 28 I.3. Adolf Sandberger versus Guido Adler 30 EXKURS II: Erich Schenks Vorgänger Robert Lach 33 2.3. Methodische Entwicklungslinien in der Wiener Musikwissen-schaft 36 2.4. Erich Schenks Welt- und Geschichtsbild 42 2.5. Erich Schenks Gutachter, Berater, Studienkollegen und Förderer 44 2.5.1. Gutachter in Erich Schenks Habilitationsverfahren 44 2.5.1.1. Johannes Wolf 44 2.5.1.2. Oskar Kaul 45 2.5.1.3. Bernhard Paumgartner 45 2.5.2. Beurteilungen betreffend eine außerordentliche Professur 47 2.5.2.1. Karl Gustav Fellerer 47 2.5.2.2. Georg Schünemann 49 2.5.2.3. Fritz Stein 50 2.5.3. Heinrich Besseler 50 2.5.4. Studienkollegen von Schenk in München 52 2.5.4.1. Karel Philippus Bernet Kempers 52 2.5.4.2. Guglielmo Barblan 53 2.5.4.3. Hans Engel 53 2.5.4.4. Josef Smits van Waesberghe S.J. 54 2.5.5. Ludwig Schiedermair 55 2.5.6. Schenks Wiener Berufungen 56 2.5.6.1. -

LCOM182 Lent & Eastertide

LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC Lent, Holy Week, and Eastertide 2018 GRACE CATHEDRAL 2 LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC GRACE CATHEDRAL SAN FRANCISCO LENT, HOLY WEEK, AND EASTERTIDE 2018 11 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LÆTARE Introit: Psalm 32:1-6 – Samuel Wesley Service: Collegium Regale – Herbert Howells Psalm 107 – Thomas Attwood Walmisley O pray for the peace of Jerusalem - Howells Drop, drop, slow tears – Robert Graham Hymns: 686, 489, 473 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Benjamin Bachmann Psalm 107 – Lawrence Thain Canticles: Evening Service in A – Herbert Sumsion Anthem: God so loved the world – John Stainer Hymns: 577, 160 15 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Canticles: Third Service – Philip Moore Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Hymns: 678, 474 18 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LENT 5 Introit: Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Service: Missa Brevis – Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Psalm 51 – T. Tertius Noble Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Motet: The crown of roses – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Hymns: 471, 443, 439 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 51 – Jeffrey Smith Canticles: Short Service – Orlando Gibbons Anthem: Aus tiefer Not – Felix Mendelssohn Hymns: 141, 151 3 22 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: William Byrd Psalm 103 – H. Walford Davies Canticles: Fauxbourdons – Thomas -

Georg Friedrich Händel

CAPPELLA „ARS MUSICA“ ÜBERREGIONALER CHOR 2004 Messiah HWV 56 Georg Friedrich Händel festschrift Georg Friedrich Händel 1685 – 1759 Messiah Georg Friedrich Händel Ingrid Haselberger, Sopran Florian Meixner, Countertenor Gerd Jaburek, Tenor Marcus Pelz, Bass Nikolaus Newerkla, Cembalo Cappella „Ars Musica“ Camerata „Ars Musica“ Einstudierung: Holger Kristen, Kurt Kren, Maria Magdalena Nödl Dirigentin Maria Magdalena Nödl mitwirkende 3 SONNTAG, 17. OKTOBER, 15.00 UHR PFARRKIRCHE TRAUNSTEIN SONNTAG, 24. OKTOBER, 16.00 UHR PFARRKIRCHE WULLERSDORF DIENSTAG, 26. OKTOBER, 16.00 UHR EGGENBURG - FESTSAAL LINDENHOF SONNTAG, 31. OKTOBER, 16.00 UHR KLOSTER PERNEGG SONNTAG, 14. NOVEMBER, 16.00 UHR STIFT ALTENBURG termine 4 Dr. Erwin Pröll Landeshauptmann von Niederösterreich Die Musik ist die beste Art der Kommunikation und die gemeinsame Sprache der Menschen. Niederösterreich verfügt über ein reiches, viel- fältiges und dynamisches Kulturleben. Der Chor Cappella „Ars Musica“ wird heuer das Wald- und Weinviertel musikalisch zum Klingen bringen. Der „Messias“ von G.F. Händel wird in fünf verschiedenen Orten aufgeführt. Und das ist auch die Philosophie der niederösterreichischen Kulturpolitik. Kunst und Kultur sind bei uns in jeder Gemeinde, in jeder Region erlebbar. Kunst und Kultur schaffen Lebensfreude, Lebensqualität, Zusammengehörig- keit und Identität. Die Musik ist zudem ein wirkungsvoller Botschafter unse- res Heimatlandes. Ich darf also dem Chor viel Erfolg und den Besuchern schöne Stunden mit dem „Messias“ wünschen. vorwort 5 Liebe Bevölkerung Yehudi Menuhin hat einmal gesagt: „Singen und Musik sind die eigent- liche Muttersprache aller Menschen, denn Musik ist die natürlichste Weise, in der wir uns ganz mitteilen können – mit all unseren Erfah- rungen, Empfindungen und Hoffnungen.“ Musik gehört also zur Natur des Menschen und ist eine der ursprünglichsten zwischenmenschlichen Ausdrucksformen. -

The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary

Alternative Services The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary Anglican Book Centre Toronto, Canada Copyright © 1985 by the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada ABC Publishing, Anglican Book Centre General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada 80 Hayden Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4Y 3G2 [email protected] www.abcpublishing.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Acknowledgements and copyrights appear on pages 925-928, which constitute a continuation of the copyright page. In the Proper of the Church Year (p. 262ff) the citations from the Revised Common Lectionary (Consultation on Common Texts, 1992) replace those from the Common Lectionary (1983). Fifteenth Printing with Revisions. Manufactured in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Anglican Church of Canada. The book of alternative services of the Anglican Church of Canada. Authorized by the Thirtieth Session of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada, 1983. Prepared by the Doctrine and Worship Committee of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada. ISBN 978-0-919891-27-2 1. Anglican Church of Canada - Liturgy - Texts. I. Anglican Church of Canada. General Synod. II. Anglican Church of Canada. Doctrine and Worship Committee. III. Title. BX5616. A5 1985 -

Cantate Concert Program May-June 2014 "Choir + Brass"

About Cantate Founded in 1997, Cantate is a mixed chamber choir comprised of professional and avocational singers whose goal is to explore mainly a cappella music from all time periods, cultures, and lands. Previous appearances include services and concerts at various Chicago-area houses of worship, the Chicago Botanic Garden’s “Celebrations” series and at Evanston’s First Night. antate Cantate has also appeared at the Chicago History Museum and the Chicago Cultural Center. For more information, visit our website: cantatechicago.org Music for Cantate Choir + Br ass Peter Aarestad Dianne Fox Alan Miller Ed Bee Laura Fox Lillian Murphy Director Benjamin D. Rivera Daniella Binzak Jackie Gredell Tracy O’Dowd Saturday, May 31, 2014 7:00 pm Sunday, June 1, 2014 7:00 pm John Binzak Dr. Anne Heider Leslie Patt Terry Booth Dennis Kalup Candace Peters Saint Luke Lutheran Church First United Methodist Church Sarah Boruta Warren Kammerer Ellen Pullin 1500 W Belmont, Chicago 516 Church Street, Evanston Gregory Braid Volker Kleinschmidt Timothy Quistorff Katie Bush Rose Kory Amanda Holm Rosengren Progr am Kyle Bush Leona Krompart Jack Taipala Joan Daugherty Elena Kurth Dirk Walvoord Canzon septimi toni #2 (1597) ....................Giovanni Gabrieli (1554–1612) Joanna Flagler Elise LaBarge Piet Walvoord Surrexit Christus hodie (1650) .......................... Samuel Scheidt (1587–1654) Canzon per sonare #1 (1608) ..............................................................Gabrieli Thou Hast Loved Righteousness (1964) .........Daniel Pinkham (1923–2006) About Our Director Sonata pian’ e forte (1597) ...................................................................Gabrieli Benjamin Rivera has been artistic director of Cantate since 2000. He has prepared and conducted choruses at all levels, from elementary Psalm 114 [116] (1852) ................................. Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) school through adult in repertoire from gospel, pop, and folk to sacred polyphony, choral/orchestral masterworks, and contemporary pieces. -

Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the Rise of the Cäcilien-Verein

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2020 Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein Nicholas Bygate Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bygate, Nicholas, "Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein" (2020). WWU Graduate School Collection. 955. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/955 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein By Nicholas Bygate Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Bertil van Boer Dr. Timothy Fitzpatrick Dr. Ryan Dudenbostel GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Interim Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. -

Ticketpreise Ticket Prices

Programmbuch · Programme book TiCketprEisE TiCkET Prices European Choir Games Eröffnungs- und Abschlusskonzert · Graz (Österreich · Austria) 2013 Opening & Closing concert: € 30,- | € 20,-*| € 20,-** | frei · free *** (Plätze begrenzt · limited seats) INTERKULTUR INTERKULTUR Österreich Festivalchor-konzert: Verdi: requiem · Ruhberg 1 · 35463 Fernwald, Germany Liebenauer Hauptstraße 2-6 Festival Choir Concert: Verdi: Requiem: Telefon · Phone: +49 (0)6404 69749-25 8041 Graz Fax: +49 (0)6404 69749-29 Austria € 69,-/59,-/49,-/29,- | € 62,-/53,-/44,-/26,-* E-mail: [email protected] € 59,-/50,-/42,-/24,-** | € 15,-/12,-/10,-/8,-*** www.europeanchoirgames.com Galakonzerte · Gala concerts: € 20,-| € 15,-*| € 15,-**| € 10,-*** Großpreis-Wettbewerb · Grand Prize Competition: € 15,-| € 10,-*| € 10,-**| frei · free *** (Plätze begrenzt · limited seats) Wettbewerbe · Competitions: Tagesticket · one-day ticket: € 10,- | € 7,-*| € 7,-** | frei · free *** Wettbewerbsabo (für alle Wettbewerbe) · competition pass (for all competition concerts): € 20,-| € 15,-*| € 15,-** | frei · free *** Freundschaftskonzerte in der steiermark · Friendship concerts in Styria: € 12,- (Vorverkauf / advance sale) € 15,- (Abendkasse / box office) € 5,- (Kinder bis 15 Jahre /children up to 15 years) Tickets erhältlich · Tickets available • Ö-Ticket Vorverkaufsstellen · Ö-Ticket offices • Kundenbüros der Kleinen Zeitung · Costumer Service Centers Kleine Zeitung • Graz Tourismus Information (Herrengasse 16, Graz), Tel: 0316/8075-0 • Online: www.oeticket.com • Ö-Ticketcenter Hotline in Graz: Tel.: 0316/8088-200 • Abendkasse an den Konzertorten · box office at the concert venues • Ticketschalter im Congress Graz · Ticket counter in Congress Graz Tickethotline: +43-664-7907231 Freundschaftskonzerte in der Steiermark: Tickets nur in den jeweiligen Konzertorten erhältlich, weitere Informationen unter www.kultur-land-leben.at · Friendship concerts in Styria: tickets 14. – 21. Juli 2013, Graz, Österreich | Austria Österreich 14. -

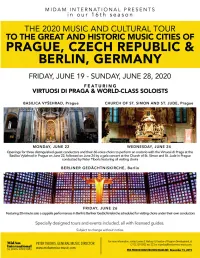

Published on February 11, 2019; Disregard All Previous Documents 1

Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 1 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 2 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 3 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 4 2020 Music Tour to Prague and Berlin Registration Deadline: November 15, 2020 Two performances in The Basilica Vyšehrad and The Church of St. Simon and St. Jude On Monday, June 22 and Wednesday, June 24 Mozart’s Vesperae solennes de confessore, K. 339 Earl Rivers, conductor College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati, Ohio And Director of Music Knox Presbyterian Church, Cincinnati, Ohio Virtuosi di Praga Oldřich Vlček, Artistic Director & World-class soloists PLUS Friday, June 26 An a cappella solo performance opportunity by visiting choirs In Berliner Gedächtniskirche A minimum of three groups must agree to perform for this concert to go forward. The Basilica Vyšehrad The Church of St. Simon and St. Jude Berliner Gedächtniskirche MidAm International, Inc. · 39 Broadway, Suite 3600 (36th FL) · New York, NY 10006 Tel. (212) 239-0205 · Fax (212) 563-5587 · www.midamerica-music.com Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 5 2020 MUSIC TOUR TO PRAGUE AND BERLIN: Itinerary Day 1 – Friday, June 19, 2020 – Arrive Prague • Arrive in Prague. MidAm International, Inc. staff and The Columbus Welcome Management staff will meet you at the airport and transfer you to Hotel Don Giovanni (http://www.hotelgiovanni.cz/en) for check-in. -

Presenting a Comprehensive Picture of Bach's Creative Genius Is One Of

Presenting a comprehensive picture of Bach’s creative genius is one of the chief objectives of the Baldwin Wallace Bach Festival. The list that follows records works performed on Festival programs since its inception in 1933. VOCAL WORKS LARGE CHORAL WORKS BWV 232, Messe in h-moll. 1935, 1936, 1940, 1946, 1947, 1951,1955, 1959, 1963, 1967, 1971, 1975, 1979, 1983, 1985, 1989, 1993, 1997, 2001, 2005, 2007, 2011, 2015, 2019. BWV 245, Johannespassion. 1937, 1941, 1948, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1964, 1968, 1972, 1976, 1980, 1984, 1990, 1994, 1998, 2002, 2006, 2010, 2014, 2018. BWV 248, Weihnachts-Oratorium. 1938, 1942, 1949, 1953, 1957, 1961, 1965, 1969, 1973, 1977, 1981, 1986, 1991, 1995, 1999, 2003, 2009, 2013. BWV 244, Matthäuspassion. 1939, 1950, 1954, 1958, 1962, 1966, 1970, 1974, 1978, 1982, 1987, 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012. BWV 243, Magnificat in D-Dur. 1933, 1934, 1937, 1939, 1943, 1945, 1946, 1950, 1957, 1962, 1968, 1976, 1984,1996, 2006, 2014. BWV 249, Oster-Oratorium. 1962, 1990. MOTETS BWV 225, Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied. 1940, 1950, 1957, 1963, 1971, 1976, 1982, 1991, 1996, 1999, 2006, 2017, 2019. BWV 226, Der Geist hilft unsrer Schwachheit auf. 1937, 1949, 1956, 1962, 1968, 1977, 1985, 1992, 1997, 2003, 2007, 2019. BWV 227, Jesu, meine Freude. 1934, 1939, 1943, 1951, 1955, 1960, 1966, 1969, 1975, 1981, 1988, 1995, 2001, 2005, 2019. BWV 228, Fürchte dich nicht, ich bin bei dir. 1936, 1947, 1952, 1958, 1964, 1972, 1979, 1995, 2002, 2016, 2019. BWV 229, Komm, Jesu, komm. 1941, 1949, 1954, 1961, 1967, 1973, 1992, 1993, 1999, 2004, 2010, 2019. -

19.05.12-19.05.25

THE QUEEN’S FREE CHAPEL THE CHAPEL OF THE COLLEGE OF ST GEORGE ST GEORGE’S CHAPEL THE CHAPEL OF THE MOST HONOURABLE & NOBLE ORDER OF THE GARTER www.stgeorges-windsor.org Services and Music from Sunday 12 to Saturday 18 May 2019 Sunday 12 8.30 am Holy Communion FOURTH SUNDAY 10.45 am Mattins Canticles: Te Deum Noble in B-minor; Jubilate Plainsong Responses: Radcliffe OF EASTER Organ Voluntary: Bach Prelude in C Major BWV 545 Psalm 146 Preacher: The Reverend Canon Dr Mark Powell, Steward Hymns 119 (107) omit vv 4-5, 295, 134 Decani (b) 12 noon Sung Eucharist Setting: Hassler Missa Secunda Hymns 416 (337), 282, 113 Gradual: Plainsong A little while, and ye shall not see me Organ Voluntary: Bach Fugue in C major BWV 545 Collections for Christian Aid and the College of St George 5.15 pm Evensong with Surplicing of Choristers Introit: Bruckner Locus iste Responses: Radcliffe Canticles: Howells St John’s Service Psalms 113 and 122 Anthem: Herbert Howells Like as the hart Hymn 336 Organ Voluntary: Howells Saraband Collection to support The Queen’s Choral Foundation Monday 13 7.30 am Mattins Psalm 103 8.00 am Holy Communion 5.15 pm Evensong Canticles: Byrd Fauxbourdons Responses: Radcliffe Anthem: Ralph Vaughan Williams I got me flowers Psalm 114 Tuesday 14 7.30 am Mattins Psalm 16 MATTHIAS 8.00 am Holy Communion 5.15 pm Evensong Canticles: Gibbons Short Service Responses: Radcliffe Anthem: Nathaniel Giles Out of the deep Psalm 80 vv 1–9 Wednesday 15 7.30 am Mattins Psalm 135 8.00 am Holy Communion 5.15 pm Evensong sung by the Choir of Hall School -

Too Many Cookes…? in This Issue: in a Review of the 2011 BBC Prom Performance of Bruckner’S

ISSN 1759-1201 www.brucknerjournal.co.uk Issued three times a year and sold by subscription FOUNDING EDITOR: Peter Palmer (1997-2004) Editor : Ken Ward [email protected] 23 Mornington Grove, London E3 4NS Subscriptions and Mailing: Raymond Cox [email protected] 4 Lulworth Close, Halesowen, B63 2UJ 01384 566383 VOLUME FIFTEEN, NUMBER THREE, NOVEMBER 2011 Associate Editor: Crawford Howie Too many Cookes…? In this issue: IN A review of the 2011 BBC Prom performance of Bruckner’s Concert Reviews Page 4 Eighth Symphony on the web-site Seenandheard- International.com, Geoff Diggines referred to the view of New Recordings Page 13 Deryck Cooke on the first printed editions of Bruckner symphonies - “abominable bowdlerisations”. Those of us who Book Review: Constantin Floros discovered Bruckner in the third quarter of the 20th century Anton Bruckner. The Man and the Work reviewed by Crawford learnt much of what we thought we knew about Bruckner and Howie and Malcolm Hatfield Page 14 the editions of his music from Cooke’s writings, and indeed, we have much to be grateful for. He wrote well, he was Bruckner’s Sonata Form Terminology devoted to the music and took it seriously, and said much that in Sketches for the Finale of the Eighth Symphony facilitated our understanding and love for this music. And in by Paul Hawkshaw Page 19 taking on board his view of versions and editions, one felt one was joining a community dedicated to the defence of Bruckner Constructing the “Bruckner Problem” against those who would impose inauthentic and vulgar by Benjamin Korstvedt Page 23 alterations upon his works. -

2014 | 2015 in Der Saison 2014 | 2015

Datum Unterschrift Datum (bitte in Blockschrift) Adresse Name und Email Tel. DIE LINZER KIRCHEN 2014 | 2015 IN DER SAISON 2014 | 2015 MARTINSKIRCHE IGNATIUSKIRCHE Martinsgasse 3 Domgasse 3 MARTIN-LUTHER-KIRCHE Johann-Konrad-Vogel Str. 2a MINORITENKIRCHE URSULINENKIRCHE Klosterstraße 7 Landstraße 31 A 4020 Linz A 39 Promenade GmbH und Orchester Theater OÖ. linz musica sacra Konzertbüro An das Eines unserer Clubhäuser. Ö1 Club-Mitglieder erhalten bei den Musica Sacra Konzerten 2,– Euro Ermäßigung. Sämtliche Ö1 Club-Vorteile Briefmarke fi nden Sie in oe1.orf.at € 0,62 INFORMATIONEN BESTELLSCHEIN musica sacra 2014 | 2015 KARTEN PREISE Preise Anzahl Kat. | € Ermäß.* Alternative** ■ A ■ B ■ C ■ D ■ Stehplatz ■ Freie Platzwahl Silent Willkommen im Preise I € 32 € 27 € 22 € 16 € 8 1 So | 19.10.2014 17.00 III Preise II € 30 € 25 € 20 € 14 € 7 Bach Motetten attaca 2 Sa | 8.11.2014 19.30 Bruckner Land Preise III € 25 € 20 € 18 € 14 € 7 V Ehrentage Alter Meister Preise IV € 20 € 18 € 16 € 12 € 6 3 So | 9.11.2014 17.00 III Oberösterreich Alleluja! Anton Bruckner Preise V € 7 € 19 Die gültige Preiseinteilung ist beim jeweiligen Konzertprogramm angeführt. Das Jahr 2014 erinnert am 4. September an Anton Bruckners 190. Geburts- Carol 4 So | 30.11.2014 17.00 II tag. Während Bruckners große sinfonische Werke landauf landab immer KARTEN KAUF Wachet auf! wieder höchst qualitätsvoll zu hören sind, ist es ein feiner Schachzug der 5 So | 7.12.2014 17.00 V ■ online auf www.musicasacra.at Veni redemptor gentium Linzer Kirchenkonzertreihe musica sacra, gerade im heurigen Jahr die kost- ■ Telefon 0800 218 000 (kostenfrei aus ganz Österreich) Die Wahrscheinlichkeit ist hoch, dass Sie es bemerkt haben: Es gibt Tage, da hängt man sprichwört- 6 So | 14.12.2014 17.00 II baren geistlichen Piecen des tiefgläubigen oberösterreichischen Meisters lich den ganzen Tag in der Leitung… Die Damen des Kartenservice des Landestheaters telefonieren Weihnachtsoratorium zu präsentieren.