Menstruation in the Jewish Tradition,” Was Written As a Part of Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 21 Course Catalogue

202021 COURSE CATALOGUE 1299 Church Road, Wyncote, Pa. 215.576.0800 RRC.edu Table of Contents I. THE RECONSTRUCTIONIST RABBINICAL COLLEGE .................................................................................... 4 Mission and Vision Statements ..................................................................................................................... 4 RRC: Our Academic Philosophy and Program ............................................................................................... 4 The Reconstructionist Movement: Intellectual Origins ................................................................................ 6 II. FACULTY .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Emeritus Faculty ............................................................................................................................................ 8 III. DEGREE PROGRAMS AND ADMISSIONS REQUIREMENTS ..................................................................... 9 Master of Arts in Hebrew Letters and Title of Rabbi .................................................................................... 9 Requests for Credit for Independent Study at RRC .................................................................................... 14 Learning Opportunities Outside of RRC, Including Transfer of Credit Policy .............................................. 14 Applying for Exemption from Requirements While at RRC ....................................................................... -

Expanding the Jewish Feminist Agenda Judith Plaskow

Expanding the Jewish Feminist Agenda Judith Plaskow ewish feminists have succeeded in changing the task of religious feminists in the new millennium is to face of Jewish religious life in the United States end this counterproductive division of labor. How can J beyond the wildest dreams of those of us who, in we hope to soli* the gains of the last decades with- the late 1960s, began to protest the exclusion of women out sophisticated analyses of power in the Jewish com- from Jewish religious practice. Thirty years ago, munity and in the larger society? How do we begin to who could have anticipated that, at the turn of the theorize and act on the ways in which creating a more century, there would be hundreds of female rabbis just Judaism is but a small piece of the larger task of representing three Jewish denominations, untold creating a more just world? numbers of female Torah and Haftorah readers, and Jewish feminists have diffidtytransforming Jew- female cantors and service leaders in synagogues ish liturgy and integrating the insights of feminist throughout the country? scholarship into Jewish education not simply because Who could have imagined that so many girls of religious barriers but also because of lack of access would expect a full bat mitzvah as a matter of course, to power and money. A 1998 study commissioned by or that Orthodox women would be learning Talmud, Ma’yan, The Jewish Women’s Project in New York, mastering synagogue skills, and functioning as full documented the deplorable absence of women from participants in services of their own? the boards of major Jewish organizations. -

Kol Hamishtakker

Kol Hamishtakker Ingredients Kol Hamishtakker Volume III, Issue 5 February 27, 2010 The Student Thought Magazine of the Yeshiva 14 Adar 5770 University Student body Paul the Apostle 3 Qrum Hamevaser: The Jewish Thought Magazine of the Qrum, by the Qrum, and for the Qrum Staph Dover Emes 4 Reexamining the Halakhot of Maharat-hood Editors-in-Chief The Vatikin (in Italy) 4 The End of an Era Sarit “Mashiah” Bendavid Shaul “The Enforcer” Seidler-Feller Ilana Basya “Tree Pile” 5 Cherem Against G-Chat Weitzentraegger Gadish Associate Editors Ilana “Good Old Gad” Gadish Some Irresponsible Feminist 7 A Short Proposal for Female Rabbis Shlomo “Yam shel Edmond” Zuckier (Pseudonym: Stephanie Greenberg) Censorship Committee Jaded Narrative 7 How to Solve the Problem of Shomer R’ M. Joel Negi’ah and Enjoy Life Better R’ Eli Baruch Shulman R’ Mayer Twersky Nathaniel Jaret 8 The Shiddukh Crisis Reconsidered: A ‘Plu- ral’istic Approach Layout Editor Menachem “Still Here” Spira Alex Luxenberg 9 Anu Ratzim, ve-Hem Shkotzim: Keeping with Menachem Butler Copy Editor Benjamin “Editor, I Barely Even Know Her!” Abramowitz Sheketah Akh Katlanit 11 New Dead Sea Sect Found Editors Emeritus [Denied Tenure (Due to Madoff)] Alex Luxenberg 13 OH MY G-DISH!: An Interview with Kol R’ Yona Reiss Hamevaser Associate Editor Ilana Gadish Alex Sonnenwirth-Ozar Friedrich Wilhelm Benjamin 13 Critical Studies: The Authorship of the Staph Writers von Rosenzweig “Documentary Hypothesis” Wikipedia Arti- A, J, P, E, D, and R Berkovitz cle Chaya “Peri Ets Hadar” Citrin Rabbi Shalom Carmy 14 Torah u-Media: A Survey of Stories True, Jake “Gush Guy” Friedman Historical, and Carmesian Nicole “Home of the Olympics” Grubner Nate “The Negi’ah Guy” Jaret Chaya Citrin 15 Kol Hamevater: A New Jewish Thought Ori “O.K.” Kanefsky Magazine of the Yeshiva University Student Alex “Grand Duchy of” Luxenberg Body Emmanuel “Flanders” Sanders Yossi “Chuent” Steinberger Noam Friedman 15 CJF Winter Missions Focus On Repairing Jonathan “’Lil ‘Ling” Zirling the World Disgraced Former Staph Writers Dr. -

TRANSGENDER JEWS and HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A

TRANSGENDER JEWS AND HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A. Sharzer MD This teshuvah was adopted by the CJLS on June 7, 2017, by a vote of 11 in favor, 8 abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, and Iscah Waldman. Members abstaining: Rabbis Noah Bickart, Baruch Frydman- Kohl, Joshua Heller, David Hoffman, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jonathan Lubliner, Micah Peltz, and Paul Plotkin. שאלות 1. What are the appropriate rituals for conversion to Judaism of transgender individuals? 2. What are the appropriate rituals for solemnizing a marriage in which one or both parties are transgender? 3. How is the marriage of a transgender person (which was entered into before transition) to be dissolved (after transition). 4. Are there any requirements for continuing a marriage entered into before transition after one of the partners transitions? 5. Are hormonal therapy and gender confirming surgery permissible for people with gender dysphoria? 6. Are trans men permitted to become pregnant? 7. How must healthcare professionals interact with transgender people? 8. Who should prepare the body of a transgender person for burial? 9. Are preoperative2 trans men obligated for tohorat ha-mishpahah? 10. Are preoperative trans women obligated for brit milah? 11. At what point in the process of transition is the person recognized as the new gender? 12. Is a ritual necessary to effect the transition of a trans person? The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halkhhah for the Conservative movement. -

Jewish Subcultures Online: Outreach, Dating, and Marginalized Communities ______

JEWISH SUBCULTURES ONLINE: OUTREACH, DATING, AND MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies ____________________________________ By Rachel Sara Schiff Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Leila Zenderland, Chair Professor Terri Snyder, Department of American Studies Professor Carrie Lane, Department of American Studies Spring, 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis explores how Jewish individuals use and create communities online to enrich their Jewish identity. The Internet provides Jews who do not fit within their brick and mortar communities an outlet that gives them voice, power, and sometimes anonymity. They use these websites to balance their Jewish identities and other personal identities that may or may not fit within their local Jewish community. This research was conducted through analyzing a broad range of websites. The first chapter, the introduction, describes the Jewish American population as a whole as well as the history of the Internet. The second chapter, entitled “The Black Hats of the Internet,” discusses how the Orthodox community has used the Internet to create a modern approach to outreach. It focuses in particular on the extensive web materials created by Chabad and Aish Hatorah, which offer surprisingly modern twists on traditional texts. The third chapter is about Jewish online dating. It uses JDate and other secular websites to analyze how Jewish singles are using the Internet. This chapter also suggests that the use of the Internet may have an impact on reducing interfaith marriage. The fourth chapter examines marginalized communities, focusing on the following: Jewrotica; the Jewish LGBT community including those who are “OLGBT” (Orthodox LGBT); Punk Jews; and feminist Jews. -

The Tifereth Israel

THE TIFERETH ISRAEL January/FebruaryFORUM 2019 | Teiveit/Sh’vat/Adar I 5779 Tu Bishvat: The Birthday of the Trees Monday, January 21, 2019 Inclusion Shabbat Shabbat Service Schedule Jan. 4 & Feb. 1 I 7:30 pm I Katz Chapel Va’era January 4-5/28 Teiveit A warm and meaningful Kabbalat Friday Evening Service 6:00 pm Shabbat for people and families with Inclusion Shabbat 7:30 pm special needs. All are welcome. For more Shabbat Warmup – ShabbaTunes 9:00 am information, contact Helen Miller at Shabbat Morning Service 9:30 am 614-236-4764. Young Peoples’ Synagogue 10:30 am Boker Tov Shabbat 11:00 am Bo January 11-12/6 Sh’vat Boker Tov Shabbat Friday Evening Service 6:00 pm Jan. 5 & Feb. 2 I 11:00 am I Katz Chapel Shabbat Warmup – Torah Talks Parsha Study 9:00 am A special Shabbat celebration for children Shabbat Morning Service - Gabrielle Schiff, bat mitzvah 9:30 am up to age 5 and their grown-ups. For more Young Peoples’ Synagogue 10:30 am information, contact Morgan at 614-928- 3286 or [email protected]. B’shalach - Anniversary Shabbat January 18-19/13 Sh’vat Wine & Cheese Oneg 5:30 pm Shabbat Neshamah: Friday Evening Musical Mindfulness Service 6:00 pm Shabbat Neshamah Shabbat Warmup – Shabbat Stretch: Light Yoga & Mindfulness 9:00 am Shabbat Morning Service - Shabbat Shira & Chelsea Wasserstrom, 9:30 am Jan. 18 & Feb. 15 I 6:00 pm I Katz Chapel bat mitzvah Nurture your spirit with Kabbalat Young Peoples’ Synagogue 10:30 am Shabbat. We start getting in the Shabbat mood in the Atrium at 5:30 pm with some Yitro - Scholar-in-Residence Shabbat January 25-26/20 Sh’vat wine and cheese, generously sponsored Friday Evening Service 6:00 pm by Fran & Steve Lesser, before moving Shabbat Dinner - by reservation 7:15 pm into the chapel for a service filled with Shabbat Warmup – Mah Chadash: What's News in Israel 9:00 am Shabbat Morning Service - sermon by Scholar in Residence 9:30 am singing, poetry, prayer, and meditation. -

Is Judaism 'Sex Positive?'

Is Judaism ‘Sex Positive?’ Understanding Trends in Recent Jewish Sexual Ethics Rebecca Epstein-Levi Introduction hen I tell people that I am a scholar of Jewish sexual eth- Wics, I am sometimes asked just what Judaism has to say about the matter. I usually give the unhelpful academic refrain of “well, it’s complicated…” or I tell the well-worn joke about “two Jews, three opinions.” The fact of the matter is that Jewish thinking on sexual ethics, as with most other things, is conten- tious, multivocal, and often contradictory. However, there are actually two levels on which this question operates. The first level is what the multiplicity of classical Jewish traditions have offered directly on matters of sexual conduct—what “Judaism says about sex.” The second level is the way modern and con- temporary thinkers have presented classical sources on sex and sexuality—what “Jewish thinkers say Judaism says about sex.” In the past seventy years or so, as the academic study of Jewish ethics has gained an institutional foothold and as rab- bis and Jewish public intellectuals have had to grapple with changes in public sexual mores and with the increasing reach of popular media, both of these levels of the question have, at least in Jewish thought in the U.S. and Canada, exhibited some clear trends. Here, I offer an analysis and a critique of these trends, especially in academic Jewish sexual ethics as it cur- rently stands, and suggest some directions for its future growth. I organize literature in modern and contemporary Jewish sexual ethics according to a typology of “cautious” versus “ex- pansive,” a typology which does not fall neatly along denomi- 14 Is Judaism ‘Sex Positive?’ national lines. -

Sexuality in Jewish Terms

Danya Ruttenberg, ed.. The Passionate Torah: Sex and Judaism. New York: New York University Press, 2009. ix + 294 pp. $19.95, paper, ISBN 978-0-8147-7605-6. Reviewed by Evyatar Marienberg Published on H-Judaic (January, 2011) Commissioned by Jason Kalman (Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion) The Passionate Torah: Sex and Judaism is a articles assembled in her volume express the delightful book. As with any publication com‐ same balanced opinion. prised of articles by various authors, not all parts Sarra Lev’s article “Sotah: Rabbinic Pornogra‐ can be honestly considered of equal importance phy?” is a remarkable analysis of the rabbinical or quality by any reader. Nevertheless, the writer description of the ritual performed on a woman of this review--who considers himself more or less suspected of unfaithfulness to her husband. Al‐ conversant in the study of Judaism and sexuality though Lev hints at the fact, and scholars such as (and who, by the way, does not know the volume’s Ishay Rosen-Zvi showed, that this ritual is proba‐ editor or the vast majority of contributors)--found bly an imaginary construct of the rabbis (using an the majority of the contributions to be, on his sub‐ actual biblical text), for readers of the Mishnah jective scale, between good and superb. for close to two millennia, the ritual was very The short introduction by Ruttenberg is a nice real. Lev, using fascinating insights from studies piece by itself. It shows clearly her intention to of pornography, forcefully shows that the text is a avoid producing yet another one-sided book on sad example of a literary pornographic descrip‐ sexuality in Judaism, in which Jewish stance on tion of an imaginary public rape--not less--pro‐ the matter is presented as simple and, not surpris‐ duced by men for consumption by men. -

Gender in Jewish Studies

Gender in Jewish Studies Proceedings of the Sherman Conversations 2017 Volume 13 (2019) GUEST EDITOR Katja Stuerzenhofecker & Renate Smithuis ASSISTANT EDITOR Lawrence Rabone A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by © University of Manchester, UK. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher, the University of Manchester, and the co-publisher, Gorgias Press LLC. All inquiries should be addressed to the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester (email: [email protected]). Co-Published by Gorgias Press LLC 954 River Road Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA Internet: www.gorgiaspress.com Email: [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4632-4056-1 ISSN 1759-1953 This volume is printed on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standard for Permanence of paper for Printed Library Materials. Printed in the United States of America Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies is distributed electronically free of charge at www.melilahjournal.org Melilah is an interdisciplinary Open Access journal available in both electronic and book form concerned with Jewish law, history, literature, religion, culture and thought in the ancient, medieval and modern eras. Melilah: A Volume of Studies was founded by Edward Robertson and Meir Wallenstein, and published (in Hebrew) by Manchester University Press from 1944 to 1955. Five substantial volumes were produced before the series was discontinued; these are now available online. -

L1teracy As the Creation of Personal Meaning in the Lives of a Select Group of Hassidic Women in Quebec

WOMEN OF VALOUR: L1TERACY AS THE CREATION OF PERSONAL MEANING IN THE LIVES OF A SELECT GROUP OF HASSIDIC WOMEN IN QUEBEC by Sharyn Weinstein Sepinwall The Department of Integrated Studies in Education A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research , in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education Faculty of Education McGiII University National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 canada Canada Our fie Notre réIérfInœ The author bas granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library ofCanada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies ofthis thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat électronique. The author retains ownership ofthe L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son pemnsslOn. autorisation. 0-612-78770-2 Canada Women of Valour: Literacy as the Creation of Personal Meaning in the Lives of a Select Group of Hassidic Women in Quebec Sharyn Weinstein Sepinwall 11 Acknowledgments One of my colleagues at McGiII in the Faculty of Management was fond of saying "writing a dissertation should change your life." Her own dissertation had been reviewed in the Wall Street Journal and its subsequent acclaim had indeed, 1surmised, changed her life. -

2017 Tikkun Program

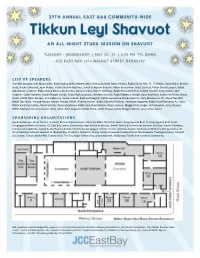

LIST OF SPEAKERS Daniella Aboody, Joel Abramovitz, Rabbi Adina Allen, Robert Alter, Deena Aranoff, Barry Barkan, Rabbi Yanky Bell, Dr. Zvi Bellin, David Biale, Rachel Biale, Rachel Binstock, Joan Blades, Rabbi Shalom Bochner, Jonah Sampson Boyarin, Robin Braverman, Reba Connell, Rabbi David Cooper, Rabbi Menachem Creditor, Rabbi Diane Elliot, Julie Emden, Danny Farkas, Ron H. Feldman, Rabbi Yehudah Ferris, Estelle Frankel, Zelig Golden, Dor Haberer, Ophir Haberer, Rabbi Margie Jacobs, Rabbi Burt Jacobson, Ameena Jandali, Rabbi Rebecca Joseph, Ilana Kaufman, Rabbi Yoel Kahn, Binya Koatz, Rabbi Dean Kertesz, Arik Labowitz, Susan Lubeck, Raphael Magarik, Rabbi Jacqueline Mates-Muchin, Judy Massarano, Dr. David Neufeld, Rabbi Dev Noily, Amanda Nube, Martin Potrop, MSW, Andrew Ramer, Rabbi Dorothy Richman, Nehama Rogozen, Rabbi Yosef Romano, Avi Rose, Rabbi SaraLeya Schley, David Schiller, Naomi Seidman, Rabbi Sara Shendelman, Noam Sienna, Maggid Jhos Singer, Idit Solomon, Jerry Strauss, MSW, Maharat Victoria Sutton, Amy Tobin, Ariel Vegosen, Rabbi Peretz Wolf-Prusan, Rabbi Bridget Wynne, and Tamar Zaken SPONSORING ORGANIZATIONS Aquarian Minyan, Bend The Arc: A Jewish Partnership for Justice, Berkeley Hillel, Chochmat HaLev, Congregation Beth El, Congregation Beth Israel, Congregation Netivot Shalom, JCC East Bay, Jewish Community High School of the Bay, Jewish Family & Community Services East Bay, Jewish Gateways, Jewish LearningWorks, Jewish Studio Project, Kehilla Community Synagogue, Keshet, Kevah, Lehrhaus Judaica, Midrasha in Berkeley, -

Forgetting Decency at Yeshiva University Commuters Distressed

THE OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF STERN COLLEGE FOR WOMEN AND SY SYMS SCHOOL OF BUSINESS The Yeshiva University OBSERVER WWW.YUOBSERVER.ORG VOLUME LXII ISSUE V JANUARY 2017/ TEVET 5777 Forgetting Decency at Yeshiva University Mindy Schwartz Managing Editor Ben Shapiro ended his widely attended speech at Yeshiva illness,” a view that was met with robust applause and cheers admittedly hostile actions towards him on CNN Headline news University on Monday night, December 5th, with a bold from the audience. constituted “deeply unladylike behavior?” More troubling still, statement: “I preach decency... If you act like a mentsch you where was this decency when many of the students in Lamport should be treated like a mentsch.” Shapiro’s claim of “mental illness” directly contradicts the laughed and clapped in response to his boast and his clever positions of the American Medical Association, the American witticism? Sitting in the audience, I felt utterly dumbfounded. Psychological Association, the American Medical Student Association, the American Public Health Association, the Kira Paley rightly pointed out Shapiro’s hypocrisy during the Decency? American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American ‘Q&A’ portion of the event. She asked, “At the end of the Academy of Pediatrics, all of whom believe that at least some speech you talked about how you preach decency...but you Ben Shapiro preaches a lot of things, but my big takeaway transgender people do possess a medical need for hormonal were clearly making jokes at the expense of transgender people. from his sermon: hypocrisy, both in his philosophy and—more and or surgical treatment.