Excerpt from Turning Points in Jewish History by Marc Rosenstein (The Jewish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Marriage Issue

Association for Jewish Studies SPRING 2013 Center for Jewish History The Marriage Issue 15 West 16th Street The Latest: New York, NY 10011 William Kentridge: An Implicated Subject Cynthia Ozick’s Fiction Smolders, but not with Romance The Questionnaire: If you were to organize a graduate seminar around a single text, what would it be? Perspectives THE MAGAZINE OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 4 The Marriage Issue Jewish Marriage 6 Bluma Goldstein Between the Living and the Dead: Making Levirate Marriage Work 10 Dvora Weisberg Married Men 14 Judith Baskin ‘According to the Law of Moses and Israel’: Marriage from Social Institution to Legal Fact 16 Michael Satlow Reading Jewish Philosophy: What’s Marriage Got to Do with It? 18 Susan Shapiro One Jewish Woman, Two Husbands, Three Laws: The Making of Civil Marriage and Divorce in a Revolutionary Age 24 Lois Dubin Jewish Courtship and Marriage in 1920s Vienna 26 Marsha Rozenblit Marriage Equality: An American Jewish View 32 Joyce Antler The Playwright, the Starlight, and the Rabbi: A Love Triangle 35 Lila Corwin Berman The Hand that Rocks the Cradle: How the Gender of the Jewish Parent Influences Intermarriage 42 Keren McGinity Critiquing and Rethinking Kiddushin 44 Rachel Adler Kiddushin, Marriage, and Egalitarian Relationships: Making New Legal Meanings 46 Gail Labovitz Beyond the Sanctification of Subordination: Reclaiming Tradition and Equality in Jewish Marriage 50 Melanie Landau The Multifarious -

Kol Hamishtakker

Kol Hamishtakker Ingredients Kol Hamishtakker Volume III, Issue 5 February 27, 2010 The Student Thought Magazine of the Yeshiva 14 Adar 5770 University Student body Paul the Apostle 3 Qrum Hamevaser: The Jewish Thought Magazine of the Qrum, by the Qrum, and for the Qrum Staph Dover Emes 4 Reexamining the Halakhot of Maharat-hood Editors-in-Chief The Vatikin (in Italy) 4 The End of an Era Sarit “Mashiah” Bendavid Shaul “The Enforcer” Seidler-Feller Ilana Basya “Tree Pile” 5 Cherem Against G-Chat Weitzentraegger Gadish Associate Editors Ilana “Good Old Gad” Gadish Some Irresponsible Feminist 7 A Short Proposal for Female Rabbis Shlomo “Yam shel Edmond” Zuckier (Pseudonym: Stephanie Greenberg) Censorship Committee Jaded Narrative 7 How to Solve the Problem of Shomer R’ M. Joel Negi’ah and Enjoy Life Better R’ Eli Baruch Shulman R’ Mayer Twersky Nathaniel Jaret 8 The Shiddukh Crisis Reconsidered: A ‘Plu- ral’istic Approach Layout Editor Menachem “Still Here” Spira Alex Luxenberg 9 Anu Ratzim, ve-Hem Shkotzim: Keeping with Menachem Butler Copy Editor Benjamin “Editor, I Barely Even Know Her!” Abramowitz Sheketah Akh Katlanit 11 New Dead Sea Sect Found Editors Emeritus [Denied Tenure (Due to Madoff)] Alex Luxenberg 13 OH MY G-DISH!: An Interview with Kol R’ Yona Reiss Hamevaser Associate Editor Ilana Gadish Alex Sonnenwirth-Ozar Friedrich Wilhelm Benjamin 13 Critical Studies: The Authorship of the Staph Writers von Rosenzweig “Documentary Hypothesis” Wikipedia Arti- A, J, P, E, D, and R Berkovitz cle Chaya “Peri Ets Hadar” Citrin Rabbi Shalom Carmy 14 Torah u-Media: A Survey of Stories True, Jake “Gush Guy” Friedman Historical, and Carmesian Nicole “Home of the Olympics” Grubner Nate “The Negi’ah Guy” Jaret Chaya Citrin 15 Kol Hamevater: A New Jewish Thought Ori “O.K.” Kanefsky Magazine of the Yeshiva University Student Alex “Grand Duchy of” Luxenberg Body Emmanuel “Flanders” Sanders Yossi “Chuent” Steinberger Noam Friedman 15 CJF Winter Missions Focus On Repairing Jonathan “’Lil ‘Ling” Zirling the World Disgraced Former Staph Writers Dr. -

SPIRITUAL JEWISH WEDDING Checklist

the SPIRITUAL JEWISH WEDDING checklist created by Micaela Ezra dear friend, Mazal tov on your upcoming wedding! I am so happy you have found your way here. I have created this very brief “Spiritual Jewish Wedding Checklist” as a guide to use as you are planning your wedding. It evolved after a conversation with Karen Cinnamon of Smashing The Glass, in response to the need for more soulful Jewish wedding inspirations and advice online. So much of the organization (as essential as it is) can distract us from the true essence of the wedding day. I hope these insights and suggestions, can help keep you on track as you navigate the process, and that as a result, the day is as meaningful for you and your guests, as it is beautiful. I wish you an easy, joyful journey as you plan, and a sublime, euphoric wedding day! With love and Blessings, For more information, or to reach out, please visit www.micaelaezra.com www.ahyinjudaica.com ONE The lead up. What’s it all about? Get clear about what the meaning of the wedding is to you. Always have at the back of your mind the essence of what you’re working to- ward. It can help you to hold things in perspective. This is a holy and sacred day, in which two halves of a soul are reunited and with G-d’s blessing and participation. The rest is decoration. How Do You Want to Feel? Clearly define HOW YOU WANT TO FEEL at your wedding, and what you want your guests to feel. -

Civil Enforcement of Jewish Marriage and Divorce: Constitutional Accommodation of a Religious Mandate

DePaul Law Review Volume 45 Issue 2 Winter 1996 Article 7 Civil Enforcement of Jewish Marriage and Divorce: Constitutional Accommodation of a Religious Mandate Jodi M. Solovy Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Jodi M. Solovy, Civil Enforcement of Jewish Marriage and Divorce: Constitutional Accommodation of a Religious Mandate, 45 DePaul L. Rev. 493 (1996) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol45/iss2/7 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIVIL ENFORCEMENT OF JEWISH MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE: CONSTITUTIONAL ACCOMMODATION OF A RELIGIOUS MANDATE INTRODUCTION When a Jewish couple marries, both parties sign an ornate docu- ment known as a ketubah. In layman's terms, the ketubah is the Jew- ish marriage license.' The majority of rabbis officiating a wedding will require the signing of a ketubah as part of the wedding ceremony. 2 Legal and Jewish scholars have interpreted the ketubah as a legally binding contract which sets out the guidelines for a Jewish marriage and divorce.3 Using this interpretation, a number of courts have re- quired that one party accommodate the other in following the speci- fied divorce proceedings that are mandated by Jewish law.4 The Jewish law requirements for a valid divorce are strict and often diffi- cult to enforce; namely, the law requires that a husband "voluntarily" give his wife a document called a get in order to dissolve the marriage according to traditional Jewish law.5 While the civil marriage contract alone binds the marriage in the eyes of the state, courts nonetheless have found the ketubah to be binding as well, and they have enforced both express and implied pro- visions of the ketubah in granting a civil dissolution of a marriage be- tween a Jewish couple. -

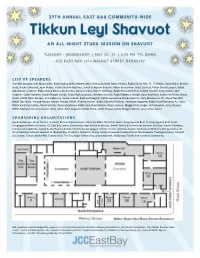

2017 Tikkun Program

LIST OF SPEAKERS Daniella Aboody, Joel Abramovitz, Rabbi Adina Allen, Robert Alter, Deena Aranoff, Barry Barkan, Rabbi Yanky Bell, Dr. Zvi Bellin, David Biale, Rachel Biale, Rachel Binstock, Joan Blades, Rabbi Shalom Bochner, Jonah Sampson Boyarin, Robin Braverman, Reba Connell, Rabbi David Cooper, Rabbi Menachem Creditor, Rabbi Diane Elliot, Julie Emden, Danny Farkas, Ron H. Feldman, Rabbi Yehudah Ferris, Estelle Frankel, Zelig Golden, Dor Haberer, Ophir Haberer, Rabbi Margie Jacobs, Rabbi Burt Jacobson, Ameena Jandali, Rabbi Rebecca Joseph, Ilana Kaufman, Rabbi Yoel Kahn, Binya Koatz, Rabbi Dean Kertesz, Arik Labowitz, Susan Lubeck, Raphael Magarik, Rabbi Jacqueline Mates-Muchin, Judy Massarano, Dr. David Neufeld, Rabbi Dev Noily, Amanda Nube, Martin Potrop, MSW, Andrew Ramer, Rabbi Dorothy Richman, Nehama Rogozen, Rabbi Yosef Romano, Avi Rose, Rabbi SaraLeya Schley, David Schiller, Naomi Seidman, Rabbi Sara Shendelman, Noam Sienna, Maggid Jhos Singer, Idit Solomon, Jerry Strauss, MSW, Maharat Victoria Sutton, Amy Tobin, Ariel Vegosen, Rabbi Peretz Wolf-Prusan, Rabbi Bridget Wynne, and Tamar Zaken SPONSORING ORGANIZATIONS Aquarian Minyan, Bend The Arc: A Jewish Partnership for Justice, Berkeley Hillel, Chochmat HaLev, Congregation Beth El, Congregation Beth Israel, Congregation Netivot Shalom, JCC East Bay, Jewish Community High School of the Bay, Jewish Family & Community Services East Bay, Jewish Gateways, Jewish LearningWorks, Jewish Studio Project, Kehilla Community Synagogue, Keshet, Kevah, Lehrhaus Judaica, Midrasha in Berkeley, -

Two Funerals and a Marriage: Symbolism and Meaning in Life Cycle Ceremonies Parashat Hayei Sarah, Genesis 23:1-25:18 | by Mark Greenspan

Two Funerals and a Marriage: Symbolism and Meaning in Life Cycle Ceremonies Parashat Hayei Sarah, Genesis 23:1-25:18 | By Mark Greenspan “The Jewish Life Cycle” by Carl Astor (pp. 239) in The Observant Life Introduction If we set aside the chronological years attributed to Abraham in the Torah, we find that his life can be divided into three periods built around the three parshiot that tell his story. Lekh L‟kha (chapters 12-17) is Abraham's youth (even though the Torah says that he was 75 when he left for Canaan). Our forefather is called by God leave his childhood home, to set out on a journey of discovery, and to carve out a place for himself in a new home. Va-yera (chapters 18-22) tells the story of his middle years as a father and a leader. Abraham develops a more mature, if not more complicated, relationship with God both testing and being tested by God. Finally, in this week's Torah portion we see Abraham in the final years of his life. Parashat Hayei Sarah begins and ends with death. Our forefather thinks about his legacy for the future, purchasing his first piece of property in Canaan and seeing to his son's marriage. With these two acts, he becomes a partner in the fulfillment of God's promise of land and people. Parshat Hayei Sarah is about the life cycle; it contains two funerals and a marriage. It is about the transition from generation to generation. Our forefather looks back and sees that he has been “blessed with everything,” despite trials and tribulations. -

Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage

Double or Nothing? mn Double or published by university press of new england hanover and london po po Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Sylvia Barack Fishman BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY PRESS nm Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, 37 Lafayette St., Lebanon, NH 03766 © 2004 by Brandeis University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fishman, Sylvia Barack, 1942– Double or nothing? : Jewish familes and mixed marriage / Sylvia Barack Fishman. p. cm.—(Brandeis series in American Jewish history, culture, and life) (Brandeis series on Jewish Women) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–58465–206–3 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Interfaith marriage—United States. 2. Jews—United States—Social conditions. 3. Jewish families—United States. I. Title. II. Series. III. Series: Brandeis series on Jewish women HQ1031.F56 2004 306.84Ј3Ј0973—dc22 2003021956 Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor Leon A. Jick, 1992 The Americanization of the Synagogue, 1820–1870 Sylvia Barack Fishman, editor, 1992 Follow My Footprints: Changing Images of Women in American Jewish Fiction Gerald Tulchinsky, 1993 Taking Root: The Origins of the Canadian Jewish Community Shalom Goldman, editor, 1993 Hebrew and the Bible in America: The First Two Centuries Marshall Sklare, 1993 Observing America’s Jews Reena Sigman Friedman, 1994 These Are Our Children: Jewish -

Kol Isha.Dwd

5778 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 86 - KOL ISHA OU ISRAEL CENTER - SPRING 2018 A] STRUCTURE The different areas of halacha which are comprised in kol isha: 1. The woman’s issues:- (i) Pritzut/Tzniut - issues of personal dignity and singing in public. (ii) Lifnei Iver - not to directly cause men to commit aveira. (iii) Ahavat Re’im - sensitivity to men’s feelings. 2. The man’s issues:- (i) Saying divrei Torah and davening etc. whilst listening to a woman’s voice. (ii) Listening to a woman’s singing to derive sensual pleasure. (iii) Ahavat Re’im - sensitivity to women’s feelings. B] THE SUGYA IN SOTAH: SINGING AND KALUT ROSH hab hbgu hrcd hrnz :;xuh cr rnt ////// wudu ihh u,ah tk rhac :rntba ',ut,anv ,hcn rhav kyc - ihrsvbx vkycan /whb,n 1. tv hnen tv hkuyck ?vbhn tepb htnk /,rugbc atf - hrcd hbgu hab hrnz 't,umhrp - /jn vyux The Mishna in Sotah deals with the loss of ‘song’ from the Jewish world after the Churban. The Gemara then discusses different types of responsive song. If the men lead the song and the women are listening and responding, that is labelled ‘pritzut’ (the opposite of tzniut). But if the women are leading the song and the men responding, that is compared to a destructive fire. Although the first case is not good, the second is far worse! vurg vatc kueu ohabv kuek ock ohb,ub ohabtv utmnbu uhrjt ,ubgk rnznv ,t gunak ubzt vyn vbugva hpk - ,rugbc atf 2. -

Mikveh and the Sanctity of Being Created Human

chapter 3 Mikveh and the Sanctity of Being Created Human Susan Grossman This paper was approved by the CJLS on September 13, 2006 by a vote of four- teen in favor, one opposed and four abstaining (14-1-4). Members voting in favor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Elliot Dorff, Aaron Mackler, Robert Harris, Robert Fine, David Wise, Daniel Nevins, Alan Lucas, Joel Roth, Myron Geller, Pamela Barmash, Gordon Tucker, Vernon Kurtz, and Susan Grossman. Members voting against: Rabbi Leonard Levy. Members abstaining: Rabbis Joseph Prouser, Loel Weiss, Paul Plotkin, and Avram Reisner. Sheilah How should we, as modern Conservative Jews, observe the laws tradition- ally referred to under the rubric Tohorat HaMishpahah (The Laws of Family Purity)?1 Teshuvah Introduction Judaism is our path to holy living, for turning the world as it is into the world as it can be. The Torah is our guide for such an ambitious aspiration, sanctified by the efforts of hundreds of generations of rabbis and their communities to 1 The author wishes to express appreciation to all the following who at different stages com- mented on this work: Dr. David Kraemer, Dr. Shaye Cohen, Dr. Seth Schwartz, Dr. Tikva Frymer-Kensky, z”l, Rabbi James Michaels, Annette Muffs Botnick, Karen Barth, and the mem- bers of the CJLS Sub-Committee on Human Sexuality. I particularly want to express my appreciation to Dr. Joel Roth. Though he never published his halakhic decisions on tohorat mishpahah (“family purity”), his lectures and teaching guided countless rabbinical students and rabbinic colleagues on this subject. In personal communication with me, he confirmed that the below psak (legal decision) and reasoning offered in his name accurately reflects his teaching. -

A Secular Jewish Wedding Ceremony and Ketubah Signing

A Secular Jewish Wedding Ceremony and Ketubah Signing Knot Note: Some names and information have been redacted for the couple’s privacy. The Ketubah Signing Ceremony Celebrant: Please gather around for this “ceremony before the ceremony”… signing of the Ketubah and the New York marriage license. Bride and Groom, in this quiet moment before your public wedding ceremony begins, those closest to you are here to witness the signing of the important documents that make this day a once-in-a-lifetime moment for you both. As you become legally husband and wife, we delight in your happiness, and we wish you only good things to come as you face life together. This beautiful Ketubah has these words for you today…words that you will see every day after you hang it in your home. I ask Groom’s father to read the words. Groom’s father reads the Ketubah Celebrant: I ask you both to sign the Ketubah as the first ceremonial act of your wedding day celebration. You two sign. Now I ask your parents to sign the Ketubah. Your parents sign. And I sign it as well. I sign. The legal document issued by the City of New York makes your marriage legal in the eyes of government and society at large. With the legal status of marriage come many rights and responsibilities which will enhance your life and also contribute to the stability and richness of the world around you. This document calls for the bride and groom’s signature. You two sign. And the signatures of two of witnesses, Andy Bock and Stacey Grippa. -

R-Manning-Kol-Isha.Pdf

בסד [email protected] אברהם םנגני - 5778 " HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 86 - KOL ISHA OU ISRAEL CENTER - SPRING 2018 A]STRUcruRE The different areas of halacha which are comprised In kol isha: 1. The woman's Issues:- (1) PrilzutjTzniut - issues of personal dignity and singlng in public . fei Iver - not to directly cause men to commit aveiraח il) Ll) (Iii) Ahavat Re'im - sensitivityto men's feelings • . ng to a woman's voice ן he man's issues:- (1) Saying divrei Torah and davenlng etc. whilst listenז •2 (ii) Llsteni ~ g to a woman's slnging to derive sensual pleasure . (iiJ) Ahavat Re'im - sensltivity to women's feellngs • N SOTAH: SINGING AND KALUI ROSHז B] JHE SUGYA .1 םתני.' משבטלה סנדהריו - נטל שהיר מנתי המשואתת, שאנמר: בשיר לא שיתן ייו יגר' " .... אמר רב ירס:ף זמרי גברי יעני נשי - פרציותא, זמרי נשי ועני גברי - שאכ בנער.תר למיא נפקא מהני? לנטולי הא מקמל הא סרטהםח. er the Churhan. The Gemara then discussesוJewish worZd qf !וom t hןThe Mishna in Sotah dea/s with the /oss oj 'song ' r women are Zistening and responding, that is Zabe//ed !וdif.!erent types ojresponsive song. ljthe men /ead the song and t h 'pritzut' (the opposite ojtzniut). But ijthe women are leading the song and the men responding, that is compared to a destructive fire. A/though the first case is not good, the second is jar worse / .2 כאש בנעירת - ~פי פכגוונכ נכטס מrנו בפנכיגו ממ כנכrנכר בגונומ מחריו וננכSמו כמנפיס נומניס בנס נקונ סנפיס וקוב נמפב גורוב בדכמינ ן;:נ«יננני ו;ןו ~, 7J ונכ,גויר ממ יSרי כמם נכגכור.מ מנב rנכרי גנרי יבכנייו כםי קSמ פריSימ ים, דקוב נמפס גוריס מכנ מיכו נכ,פיר יSר, כ~ בן םמיז בנכrנכריס נכיטס מrנס ~קיב בפוכיס '''שר טוסה חם. -

RITES of PASSAGE - MARRIAGE Starter: Recall Questions 1

Thursday, January 28, 2021 RITES OF PASSAGE - MARRIAGE Starter: Recall Questions 1. What does a Sandek do in Judaism? 2. What is the literal translation of bar mitzvah? 3. A girl becomes a bat mitzvah at what age? 4. Under Jewish law, children become obligated to observe the what of Jewish law after their bar/bat mitzvah 5. What is the oral law? All: To examine marriage trends in the Learning 21st century. Intent Most: To analyse the most important customs and traditions in a Jewish marriage ceremony. Some: assess the difference in the approach on marriage in Jewish communities/ consider whether marriage is relevant in the 21 century. Key Terms for this topic 1. Adultery: Sexual intercourse between a married person and another person who is not their spouse. 2. Agunah: Women who are 'chained' metaphorically because their husbands have not applied for a 'get' or refused to give them one. 3. Ashkenazi Jew:A Jew who has descended from traditionally German-speaking countries in Central and Eastern Europe. 4. Chuppah: A canopy used during a Jewish wedding. It is representative of the couple’s home. 5. Cohabitation: Living together without being married. 6. Conservative: These are believers that prefer to keep to old ways and only reluctantly allow changes in traditional beliefs and practices. 7. Divorce: A legal separation of the marriage partners. 8. family purity: A system of rules observed by Jews whereby husband and wife do not engage in sexual relations or any physical contact from the onset of menstruation until 7 days after its end and the woman has purified herself at the mikvah.