Insecurity in the Gulf of Guinea: Assessing the Threats, Preparing the Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

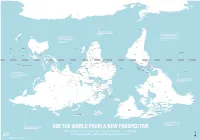

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Addressing the Atlantic's Emerging Security Challenges

34 Addressing the Atlantic’s Emerging Security Challenges Bruno Lété The German Marshall Fund of the United States ABSTRACT As the Atlantic space is expected to continue to play a global role, it is not surprising that nations around the Atlantic have become increasingly concerned about securing the region’s commons at land, at sea, and in the air. In much contrast to the territorial disputes and military tensions defining the Pacific Rim, the Atlantic remains a relatively stable geo-political sphere, largely due to the lack of great power conflict. But the prominence of the region in security and military considerations is rising, especially with the aim to combat illegal activities. This paper identifies three emerging security challenges that may jeopardize the future peace and prosperity of all the countries surrounding the Atlantic Ocean if they are left unresolved. The first draft of this Scientific Paper was presented at the ATLANTIC FUTURE Seminar, Lisbon, 24 April 2015 ATLANTIC FUTURE SCIENTIFIC PAPER 34 Table of contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 3 2. The Atlantic remains a key region in a rapidly changing global system ...................................................................................................... 3 3. Three emerging challenges affect security in the Atlantic ....... 4 4. A pan-Atlantic approach is lacking ...................................................... 9 5. Conclusion .................................................................................................. -

From Operation Serval to Barkhane

same year, Hollande sent French troops to From Operation Serval the Central African Republic (CAR) to curb ethno-religious warfare. During a visit to to Barkhane three African nations in the summer of 2014, the French president announced Understanding France’s Operation Barkhane, a reorganization of Increased Involvement in troops in the region into a counter-terrorism Africa in the Context of force of 3,000 soldiers. In light of this, what is one to make Françafrique and Post- of Hollande’s promise to break with colonialism tradition concerning France’s African policy? To what extent has he actively Carmen Cuesta Roca pursued the fulfillment of this promise, and does continued French involvement in Africa constitute success or failure in this rançois Hollande did not enter office regard? France has a complex relationship amid expectations that he would with Africa, and these ties cannot be easily become a foreign policy president. F cut. This paper does not seek to provide a His 2012 presidential campaign carefully critique of President Hollande’s policy focused on domestic issues. Much like toward France’s former African colonies. Nicolas Sarkozy and many of his Rather, it uses the current president’s predecessors, Hollande had declared, “I will decisions and behavior to explain why break away from Françafrique by proposing a France will not be able to distance itself relationship based on equality, trust, and 1 from its former colonies anytime soon. solidarity.” After his election on May 6, It is first necessary to outline a brief 2012, Hollande took steps to fulfill this history of France’s involvement in Africa, promise. -

The North Caucasus: the Challenges of Integration (III), Governance, Elections, Rule of Law

The North Caucasus: The Challenges of Integration (III), Governance, Elections, Rule of Law Europe Report N°226 | 6 September 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Russia between Decentralisation and the “Vertical of Power” ....................................... 3 A. Federative Relations Today ....................................................................................... 4 B. Local Government ...................................................................................................... 6 C. Funding and budgets ................................................................................................. 6 III. Elections ........................................................................................................................... 9 A. State Duma Elections 2011 ........................................................................................ 9 B. Presidential Elections 2012 ...................................................................................... -

Country by Country Reporting

COUNTRY BY COUNTRY REPORTING PUBLICATION REPORT 2018 (REVISED) Anglo American is a leading global mining company We take a responsible approach to the management of taxes, As we strive to deliver attractive and sustainable returns to our with a world class portfolio of mining and processing supporting active and constructive engagement with our stakeholders shareholders, we are acutely aware of the potential value creation we operations and undeveloped resources. We provide to deliver long-term sustainable value. Our approach to tax is based can offer to our diverse range of stakeholders. Through our business on three key pillars: responsibility, compliance and transparency. activities – employing people, paying taxes to, and collecting taxes the metals and minerals to meet the growing consumer We are proud of our open and transparent approach to tax reporting. on behalf of, governments, and procuring from host communities – driven demands of the world’s developed and maturing In addition to our mandatory disclosure obligations, we are committed we make a significant and positive contribution to the jurisdictions in economies. And we do so in a way that not only to furthering our involvement in voluntary compliance initiatives, such which we operate. Beyond our direct mining activities, we create and generates sustainable returns for our shareholders, as the Tax Transparency Code (developed by the Board of Taxation in sustain jobs, build infrastructure, support education and help improve but also strives to make a real and lasting positive Australia), the Responsible Tax Principles (developed by the B Team), healthcare for employees and local communities. By re-imagining contribution to society. -

99 UPWELLING in the GULF of GUINEA Results of a Mathematical

99 UPWELLING IN THE GULF OF GUINEA Results of a mathematical model 2 2 6 5 0 A. BAH Mécanique des Fluides géophysiques, Université de Liège, Liège (Belgium) ABSTRACT A numerical simulation of the oceanic response of an x-y-t two-layer model on the 3-plane to an increase of the wind stress is discussed in the case of the tro pical Atlantic Ocean. It is shown first that the method of mass transport is more suitable for the present study than the method of mean velocity, especially in the case of non-linearity. The results indicate that upwelling in the oceanic equatorial region is due to the eastward propagating equatorially trapped Kelvin wave, and that in the coastal region upwelling is due to the westward propagating reflected Rossby waves and to the poleward propagating Kelvin wave. The amplification due to non- linearity can be about 25 % in a month. The role of the non-rectilinear coast is clearly shown by the coastal upwelling which is more intense east than west of the three main capes of the Gulf of Guinea; furthermore, by day 90 after the wind's onset, the maximum of upwelling is located east of Cape Three Points, in good agree ment with observations. INTRODUCTION When they cross over the Gulf of Guinea, monsoonal winds take up humidity and subsequently discharge it over the African Continent in the form of precipitation (Fig. 1). The upwelling observed during the northern hemisphere summer along the coast of the Gulf of Guinea can reduce oceanic evaporation, and thereby affect the rainfall pattern in the SAHEL region. -

Chirac and ‘La Franc¸Afrique’: No Longer a Family Affair Tony Chafer

Modern & Contemporary France Vol. 13, No. 1, February 2005, pp. 7–23 Chirac and ‘la Franc¸afrique’: No Longer a Family Affair Tony Chafer Since political independence, France has maintained a privileged sphere of influence—the so-called ‘pre´ carre´’—in sub-Saharan Africa, based on a series of family-like ties with its former colonies. The cold war provided a favourable environment for the development of this special relationship, as the USA saw the French presence in this part of the world as useful for the containment of Communism. However, following the end of the cold war, France has had to adapt to a new international policy environment that is more competitive and less conducive to the maintenance of such family-like ties. This article charts the evolution of Franco-African relations in an era of globalisation, as French governments have undertaken a hesitant process of policy adaptation since the mid-1990s. Unlike decolonisation in Indochina and Algeria, the transfer of power in Black Africa was largely peaceful; as a result, there was no rupture of relations with the former colonial power. On the contrary, the years after independence were marked by an intensification of the links with France. Official rhetoric often referred to the great Franco-African family and the term ‘la Franc¸afrique’ testified to a symbiotic relationship in which ‘Africa is experienced in French representations as a natural extension where the Francophone world and Francophilia merge’ (Bourmaud, 2000). In fact, a wide variety of terms have been coined to describe -

Is Map Is Just As Accurate As the One We're All Used To

ROSS SEA WEDDELL SEA AMUNDSEN SEA ANTARCTICA BELLINGSHAUSEN SEA AMERY ICE SHELF SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SCOTIA SEA DRAKE PASSAGE FALKLAND ISLANDS Stanley (U.K.) THE RATIO OF LAND TO WATER IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE BY THE TIME EUROPEANS ADOPTED IS 1 TO 5 THE NORTH-POINTING COMPASS, PTOLEMY WAS A HELLENIC Wellington THEY WERE ALREADY EXPERIENCED NEW TASMAN SEA ZEALAND CARTOGRAPHER WHOSE WORK CHILE IN NAVIGATING WITH REFERENCE TO IN THE SECOND CENTURY A.D. ARGENTINA THE NORTH STAR Canberra Buenos Santiago GREAT AUSTRALIAN BIGHT POPULARIZED NORTH-UP Montevideo Aires SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN URUGUAY ORIENTATION SOUTH AFRICA Maseru LESOTHO SWAZILAND Mbabane Maputo Asunción AUSTRALIA Pretoria Gaborone NEW Windhoek PARAGUAY TONGA Nouméa CALEDONIA BOTSWANA Saint Denis NAMIBIA Nuku’Alofa (FRANCE) MAURITIUS Port Louis Antananarivo MOZAMBIQUE CHANNEL ZIMBABWE Suva Port Vila MADAGASCAR VANUATU MOZAMBIQUE Harare La Paz INDIAN OCEAN Brasília LAKE SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN FIJI Lusaka TITICACA CORAL SEA GREAT GULF OF BARRIER CARPENTARIA Lilongwe ZAMBIA BOLIVIA FRENCH POLYNESIA Apia REEF LAKE (FRANCE) SAMOA TIMOR SEA COMOROS NYASA ANGOLA Lima Moroni MALAWI Honiara ARAFURA SEA BRAZIL TIMOR LESTE PERU Funafuti SOLOMON Port Dili Luanda ISLANDS Moresby LAKE Dodoma TANGANYIKA TUVALU PAPUA Jakarta SEYCHELLES TANZANIA NEW GUINEA Kinshasa Victoria BURUNDI Bujumbura DEMOCRATIC KIRIBATI Brazzaville Kigali REPUBLIC LAKE OF THE CONGO SÃO TOMÉ Nairobi RWANDA GABON ECUADOR EQUATOR INDONESIA VICTORIA REP. OF AND PRINCIPE KIRIBATI EQUATOR -

THE LIMITS of SELF-DETERMINATION in OCEANIA Author(S): Terence Wesley-Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies, Vol

THE LIMITS OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN OCEANIA Author(s): Terence Wesley-Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies, Vol. 56, No. 1/2, The Caribbean and Pacific in a New World Order (March/June 2007), pp. 182-208 Published by: Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, University of the West Indies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27866500 . Accessed: 11/10/2013 20:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of the West Indies and Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social and Economic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 133.30.14.128 on Fri, 11 Oct 2013 20:07:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Social and Economic Studies 56:1&2 (2007): 182-208 ISSN:0037-7651 THE LIMITS OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN OCEANIA Terence Wesley-Smith* ABSTRACT This article surveys processes of decolonization and political development inOceania in recent decades and examines why the optimism of the early a years of self government has given way to persistent discourse of crisis, state failure and collapse in some parts of the region. -

Interim Guidelines for Owners, Operators and Masters for Protection Against Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea Region

Interim Guidelines for Owners, Operators and Masters for protection against piracy in the Gulf of Guinea region (To be read in conjunction with BMP4) 1. Introduction Piracy and armed robbery (hereafter referred to as piracy) in the Gulf of Guinea region is an established criminal activity and is of increasing concern to the maritime sector. With recent attacks becoming more widespread and violent, industry has now identified an urgent need to issue these Guidelines. Although piracy in the Gulf of Guinea region in many ways differs from that of Somalia based piracy, large sections of the Best Management Practices already developed by industry to help protect against Somalia based piracy are also valid in the Gulf of Guinea region. Consequently, these interim Guidelines aim to bridge the gap between the advice currently found in BMP4 and the prevailing situation in the Gulf of Guinea region. Consequently, these guidelines should be read in conjunction with BMP4 and will make reference to BMP4 where relevant. These interim Guidelines have been developed by BIMCO, ICS, INTERCARGO and INTERTANKO, and are supported by NATO Shipping Centre. A soft copy of BMP4 can be found on the websites of these organisations. 2. Area for consideration Pirates in the Gulf of Guinea are flexible in their operations so it is difficult to predict a precise area of falling victim to piracy. As of 28 March 2012 the London Market’s Joint War Committee defines the following ‘Listed Areas for Hull War, Piracy, Terrorism and Related Perils’ for the Gulf of Guinea: • The territorial waters of Benin and Nigeria, plus • Nigerian Exclusive Economic Zone north of latitude 3º N, plus • Beninese Exclusive Economic Zones north of latitude 3º N. -

195 the Gulf of Guinea

THE GULF OF GUINEA: THE NEW DANGER ZONE Africa Report N°195 – 12 December 2012 Translation from French TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. A STRATEGIC REGION IN THE GRIP OF INSECURITY ...................................... 2 A. RENEWED STRATEGIC INTEREST IN NATURAL RESOURCES .......................................................... 2 B. A CONTEXT FAVOURABLE TO MARITIME CRIME ......................................................................... 3 C. WEAK MARITIME POLICIES .......................................................................................................... 4 III. NIGERIA: EPICENTRE OF VIOLENCE AT SEA ...................................................... 6 A. POOR GOVERNANCE AND MARITIME CRIME ................................................................................ 6 1. A leaky oil sector ......................................................................................................................... 6 2. The rise in economic crime .......................................................................................................... 7 3. State capacity hampered by corruption ........................................................................................ 8 4. The Niger Delta ........................................................................................................................... -

4 European Policy and Energy Interests – Challenges from the Gulf of Guinea ␣

CHAPTER I OIL POLICY IN THE GULF OF GUINEA 4 European Policy and Energy Interests – Challenges from the Gulf of Guinea ␣ By Lutz Neumann 1. Introduction ␣ The Gulf of Guinea has great oil and gas potential. While predictions on Africa should be made with some care, analysts and representatives of the oil industry appear to agree that the region belongs to those areas where production will rapidly increase in the coming years and decades. Output figures of the chief oil- producing countries, Nigeria and Angola, are expected to double or triple within the next decade and thus will cause certain dynamics on the shaping of trade movements (see table 1). Table 1: Projected Oil Production of Gulf of Guinea 2005-2030 (in b/d) 2005 2010 2015 2030 Nigeria 2,719,000 3,042,000 3,729,000 4,422,000 Angola 1,098,000 2,026,000 2,549,000 3,288,000 Equatorial-Guinea 313,000 466,000 653,000 724,000 Congo (Brazzaville) 285,000 300,000 314,000 327,000 Gabon 303,000 291,000 279,000 269,000 Côte d’Ivoire 43,000 71,000 83,000 94,000 Cameroun 84,000 72,000 66,000 61,000 Congo (Kinshasa) 30,000 33,000 30,000 25,000 Ghana 11,000 16,000 20,000 23,000 Total Africa 9,936,000 12,059,000 13,975,000 16,242,000 Source: EIA, U.S. Department of Energy.␣ FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG 59 OIL POLICY IN THE GULF OF GUINEA CHAPTER I The African countries along the Atlantic coast represent a growing supplier region.