4 European Policy and Energy Interests – Challenges from the Gulf of Guinea ␣

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addressing the Atlantic's Emerging Security Challenges

34 Addressing the Atlantic’s Emerging Security Challenges Bruno Lété The German Marshall Fund of the United States ABSTRACT As the Atlantic space is expected to continue to play a global role, it is not surprising that nations around the Atlantic have become increasingly concerned about securing the region’s commons at land, at sea, and in the air. In much contrast to the territorial disputes and military tensions defining the Pacific Rim, the Atlantic remains a relatively stable geo-political sphere, largely due to the lack of great power conflict. But the prominence of the region in security and military considerations is rising, especially with the aim to combat illegal activities. This paper identifies three emerging security challenges that may jeopardize the future peace and prosperity of all the countries surrounding the Atlantic Ocean if they are left unresolved. The first draft of this Scientific Paper was presented at the ATLANTIC FUTURE Seminar, Lisbon, 24 April 2015 ATLANTIC FUTURE SCIENTIFIC PAPER 34 Table of contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 3 2. The Atlantic remains a key region in a rapidly changing global system ...................................................................................................... 3 3. Three emerging challenges affect security in the Atlantic ....... 4 4. A pan-Atlantic approach is lacking ...................................................... 9 5. Conclusion .................................................................................................. -

99 UPWELLING in the GULF of GUINEA Results of a Mathematical

99 UPWELLING IN THE GULF OF GUINEA Results of a mathematical model 2 2 6 5 0 A. BAH Mécanique des Fluides géophysiques, Université de Liège, Liège (Belgium) ABSTRACT A numerical simulation of the oceanic response of an x-y-t two-layer model on the 3-plane to an increase of the wind stress is discussed in the case of the tro pical Atlantic Ocean. It is shown first that the method of mass transport is more suitable for the present study than the method of mean velocity, especially in the case of non-linearity. The results indicate that upwelling in the oceanic equatorial region is due to the eastward propagating equatorially trapped Kelvin wave, and that in the coastal region upwelling is due to the westward propagating reflected Rossby waves and to the poleward propagating Kelvin wave. The amplification due to non- linearity can be about 25 % in a month. The role of the non-rectilinear coast is clearly shown by the coastal upwelling which is more intense east than west of the three main capes of the Gulf of Guinea; furthermore, by day 90 after the wind's onset, the maximum of upwelling is located east of Cape Three Points, in good agree ment with observations. INTRODUCTION When they cross over the Gulf of Guinea, monsoonal winds take up humidity and subsequently discharge it over the African Continent in the form of precipitation (Fig. 1). The upwelling observed during the northern hemisphere summer along the coast of the Gulf of Guinea can reduce oceanic evaporation, and thereby affect the rainfall pattern in the SAHEL region. -

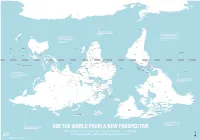

Is Map Is Just As Accurate As the One We're All Used To

ROSS SEA WEDDELL SEA AMUNDSEN SEA ANTARCTICA BELLINGSHAUSEN SEA AMERY ICE SHELF SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SCOTIA SEA DRAKE PASSAGE FALKLAND ISLANDS Stanley (U.K.) THE RATIO OF LAND TO WATER IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE BY THE TIME EUROPEANS ADOPTED IS 1 TO 5 THE NORTH-POINTING COMPASS, PTOLEMY WAS A HELLENIC Wellington THEY WERE ALREADY EXPERIENCED NEW TASMAN SEA ZEALAND CARTOGRAPHER WHOSE WORK CHILE IN NAVIGATING WITH REFERENCE TO IN THE SECOND CENTURY A.D. ARGENTINA THE NORTH STAR Canberra Buenos Santiago GREAT AUSTRALIAN BIGHT POPULARIZED NORTH-UP Montevideo Aires SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN URUGUAY ORIENTATION SOUTH AFRICA Maseru LESOTHO SWAZILAND Mbabane Maputo Asunción AUSTRALIA Pretoria Gaborone NEW Windhoek PARAGUAY TONGA Nouméa CALEDONIA BOTSWANA Saint Denis NAMIBIA Nuku’Alofa (FRANCE) MAURITIUS Port Louis Antananarivo MOZAMBIQUE CHANNEL ZIMBABWE Suva Port Vila MADAGASCAR VANUATU MOZAMBIQUE Harare La Paz INDIAN OCEAN Brasília LAKE SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN FIJI Lusaka TITICACA CORAL SEA GREAT GULF OF BARRIER CARPENTARIA Lilongwe ZAMBIA BOLIVIA FRENCH POLYNESIA Apia REEF LAKE (FRANCE) SAMOA TIMOR SEA COMOROS NYASA ANGOLA Lima Moroni MALAWI Honiara ARAFURA SEA BRAZIL TIMOR LESTE PERU Funafuti SOLOMON Port Dili Luanda ISLANDS Moresby LAKE Dodoma TANGANYIKA TUVALU PAPUA Jakarta SEYCHELLES TANZANIA NEW GUINEA Kinshasa Victoria BURUNDI Bujumbura DEMOCRATIC KIRIBATI Brazzaville Kigali REPUBLIC LAKE OF THE CONGO SÃO TOMÉ Nairobi RWANDA GABON ECUADOR EQUATOR INDONESIA VICTORIA REP. OF AND PRINCIPE KIRIBATI EQUATOR -

195 the Gulf of Guinea

THE GULF OF GUINEA: THE NEW DANGER ZONE Africa Report N°195 – 12 December 2012 Translation from French TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. A STRATEGIC REGION IN THE GRIP OF INSECURITY ...................................... 2 A. RENEWED STRATEGIC INTEREST IN NATURAL RESOURCES .......................................................... 2 B. A CONTEXT FAVOURABLE TO MARITIME CRIME ......................................................................... 3 C. WEAK MARITIME POLICIES .......................................................................................................... 4 III. NIGERIA: EPICENTRE OF VIOLENCE AT SEA ...................................................... 6 A. POOR GOVERNANCE AND MARITIME CRIME ................................................................................ 6 1. A leaky oil sector ......................................................................................................................... 6 2. The rise in economic crime .......................................................................................................... 7 3. State capacity hampered by corruption ........................................................................................ 8 4. The Niger Delta ........................................................................................................................... -

Influence of the Gulf of Guinea Coastal and Equatorial Upwellings on the Precipitations Along Its Northern Coasts During the Boreal Summer Period

Asian Journal of Applied Sciences 4 (3): 271-285, 2011 ISSN 1996-3343 I DOI: 10.3923/ajaps.2011.271.285 © 2011 Knowledgia Review, Malaysia Influence of the Gulf of Guinea Coastal and Equatorial Upwellings on the Precipitations along its Northern Coasts during the Boreal Summer Period 'K.E. Ali, 'K.Y. Kouadio, 'E.-P. Zahiri, 'A. Aman, 'A.P. Assamoi and 2B. Bourles 'LAPAMF, Universite de Cocody-Abidjan BP 231 Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire 2IRD/LEGOS-CRHOB, Representation !RD, 08 BP 841 Cotonou, Republique du Benin Corresponding Author: Angora Aman, Universite de Cocody-Abidjan 22 BP 582 Abidjan 22, LAPA-MF, UFR-SSMT, Cote d'Ivoire Tel: (225) 07 82 77 52 Fax: (225) 22 44 14 07 ABSTRACT The Gulf of Guinea (GG) is an area where a seasonal upwelling takes place, along the equator and its northern coasts between Benin and Cote d'Ivoire. The coastal upwelling has a real impact on the local yet documented biological resources. However, climatic impact studies of this seasonal upwelling are paradoxically very rare and disseminated and this impact is still little known, especially on the potential part played by the upwelling onset on the regional precipitation in early boreal summer. This study shows that coastal precipitations of the July-September period are correlated by both the coastal and equatorial sea-surface temperatures (SSTS). This correlation results in a decrease or a rise of rainfall when the SSTs are abnormally cold or warm respectively. The coastal areas that are more subject to coastal and equatorial SSTs influence are located around the Cape Three Points, where the coastal upwelling exhibits the maximum of amplitude. -

Atlantic Ocean Equatorial Currents

188 ATLANTIC OCEAN EQUATORIAL CURRENTS ATLANTIC OCEAN EQUATORIAL CURRENTS S. G. Philander, Princeton University, Princeton, Centered on the equator, and below the westward NJ, USA surface Sow, is an intense eastward jet known as the Equatorial Undercurrent which amounts to a Copyright ^ 2001 Academic Press narrow ribbon that precisely marks the location of doi:10.1006/rwos.2001.0361 the equator. The undercurrent attains speeds on the order of 1 m s\1 has a half-width of approximately Introduction 100 km; its core, in the thermocline, is at a depth of approximately 100 m in the west, and shoals to- The circulations of the tropical Atlantic and PaciRc wards the east. The current exists because the west- Oceans have much in common because similar trade ward trade winds, in addition to driving divergent winds, with similar seasonal Suctuations, prevail westward surface Sow (upwelling is most intense at over both oceans. The salient features of these circu- the equator), also maintain an eastward pressure lations are alternating bands of eastward- and west- force by piling up the warm surface waters in the ward-Sowing currents in the surface layers (see western side of the ocean basin. That pressure force Figure 1). Fluctuations of the currents in the two is associated with equatorward Sow in the thermo- oceans have similarities not only on seasonal but cline because of the Coriolis force. At the equator, even on interannual timescales; the Atlantic has where the Coriolis force vanishes, the pressure force a phenomenon that is the counterpart of El Ninoin is the source of momentum for the eastward Equa- the PaciRc. -

Articles from the Free Tropo

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 5373–5390, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-5373-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Downward cloud venting of the central African biomass burning plume during the West Africa summer monsoon Alima Dajuma1,3, Kehinde O. Ogunjobi1,4, Heike Vogel2, Peter Knippertz2, Siélé Silué5, Evelyne Touré N’Datchoh3, Véronique Yoboué3, and Bernhard Vogel2 1Department of Meteorology and Climate Sciences, West African Science Service Centre on Climate Change and Adapted Land Use (WASCAL), Federal University of Technology Akure (FUTA), Ondo State, Nigeria 2Institute of Meteorology and Climate Research, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Karlsruhe, Germany 3University Félix Houphouët Boigny, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire 4Federal University of Technology Akure (FUTA), Ondo State, Nigeria 5Université Peleforo Gon Coulibaly, Korhogo, Côte d’Ivoire Correspondence: Alima Dajuma ([email protected]) Received: 29 June 2019 – Discussion started: 9 August 2019 Revised: 3 April 2020 – Accepted: 4 April 2020 – Published: 7 May 2020 Abstract. Between June and September large amounts of clouds and rainfall over the Gulf of Guinea. Using the CO biomass burning aerosol are released into the atmosphere dispersion as an indicator for the biomass burning plume, we from agricultural fires in central and southern Africa. Re- identify individual mixing events south of the coast of Côte cent studies have suggested that this plume is carried west- d’Ivoire due to midlevel convective clouds injecting parts of ward over the Atlantic Ocean at altitudes between 2 and the biomass burning plume into the PBL. Idealized tracer ex- 4 km and then northward with the monsoon flow at low lev- periments suggest that around 15 % of the CO mass from els to increase the atmospheric aerosol load over coastal the 2–4 km layer is mixed below 1 km within 2 d over the cities in southern West Africa (SWA), thereby exacerbat- Gulf of Guinea and that the magnitude of the cloud venting is ing air pollution problems. -

Towards a National Ocean Policy in Sao Tome And

TOWARDS A NATIONAL OCEAN POLICY IN SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE Mé-Chinhô Costa Alegre The United Nations-Nippon Foundation Fellowship Programme 2009 - 2010 DIVISION FOR OCEAN AFFAIRS AND THE LAW OF THE SEA OFFICE OF LEGAL AFFAIRS, THE UNITED NATIONS NEW YORK, 2009 DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Sao Tome and Principe, the United Nations, the Nippon Foundation of Japan, or the University of West Indies. © 2009 Me-Chinho Costa Alegre. All rights reserved. - i - Abstract The Oceans role to Earth’s environment is broadly recognized and thus there is a growing awareness on environment issues in order to secure preservation of marine resources, food security, sustainability of life at sea and cope with the effects of climate change. Considering that Sao Tome and Principe is a Small Island Developing State (SIDS), a attention will be given to the strategies, policies, legal and institutional approaches among the SIDS around the world and particularly in the Caribbean Region, paying special attention to Barbados experience. The report will consider too the strong pressure on coastal land for construction, tourism developments and other economic activities. The report addresses these issues with reference to the predictable constraint of limited human and financial resources typical of SIDS. In addition, international cooperation among SIDS will be examined in order to understand the Regional integrated policies and strategies needed to tackle common concerns and improve efficiency in the application of resources to implement international instruments. The concept of a Large Marine Ecosystem approach is considered in this analysis of regional cooperation. -

Table 2. Geographic Areas, and Biography

Table 2. Geographic Areas, and Biography The following numbers are never used alone, but may be used as required (either directly when so noted or through the interposition of notation 09 from Table 1) with any number from the schedules, e.g., public libraries (027.4) in Japan (—52 in this table): 027.452; railroad transportation (385) in Brazil (—81 in this table): 385.0981. They may also be used when so noted with numbers from other tables, e.g., notation 025 from Table 1. When adding to a number from the schedules, always insert a decimal point between the third and fourth digits of the complete number SUMMARY —001–009 Standard subdivisions —1 Areas, regions, places in general; oceans and seas —2 Biography —3 Ancient world —4 Europe —5 Asia —6 Africa —7 North America —8 South America —9 Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds —001–008 Standard subdivisions —009 History If “history” or “historical” appears in the heading for the number to which notation 009 could be added, this notation is redundant and should not be used —[009 01–009 05] Historical periods Do not use; class in base number —[009 1–009 9] Geographic treatment and biography Do not use; class in —1–9 —1 Areas, regions, places in general; oceans and seas Not limited by continent, country, locality Class biography regardless of area, region, place in —2; class specific continents, countries, localities in —3–9 > —11–17 Zonal, physiographic, socioeconomic regions Unless other instructions are given, class -

Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea: EU and International Action

BRIEFING Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea EU and international action SUMMARY The Gulf of Guinea is framed by 6 000 km of west African coastline, from Senegal to Angola. Its sea basin is an important resource for fisheries and is part of a key sea route for the transport of goods between central and southern Africa and the rest of the world. Its geo-political and geo-economic importance has grown since it has become a strategic hub in global and regional energy trade. Every day, nearly 1 500 fishing vessels, cargo ships and tankers navigate its waters. The security of this maritime area is threatened by the rise of piracy, illegal fishing, and other maritime crimes. Regional actors have committed to cooperate on tackling the issue through the 'Yaoundé Code of Conduct' and the related cooperation mechanism and bodies. The international community has also pledged to track and condemn acts of piracy at sea. The European Union (EU), which has a strong interest in safeguarding its maritime trade and in addressing piracy's root causes, supports regional and international initiatives. The EU is also implementing its own maritime security strategy, which includes, among other features, a regional component for the Gulf of Guinea; this entails EU bodies' and Member States' cooperation in countering acts of piracy, as well as capacity-building projects. This briefing draws from and updates the sections on the Gulf of Guinea in 'Piracy and armed robbery off the coast of Africa', EPRS, March 2019. In this Briefing Background Regional cooperation International action EU strategies Map of the Gulf of Guinea and ECOWAS and ECCAS member states. -

Differences and Similarities Between Gulf of Guinea and Somalia Maritime Piracy: Lessons Gulf of Guinea Coastal States Should Learn from Somali Piracy

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3240 (Paper) ISSN 2224-3259 (Online) Vol.56, 2016 Differences and Similarities between Gulf of Guinea and Somalia Maritime Piracy: Lessons Gulf of Guinea Coastal States Should Learn from Somali Piracy Devotha Edward Mandanda * Prof. Dr. GUO Ping School of Law, Dalian Maritime University, No. 1 Linghai Road, High-Tech Zone District, Dalian City, Liaoning Province, Post Code 116026, China Abstract Maritime piracy in African waters started to flourish in 21 st century when Pirates focus their activities in the two sides of the Continent. Between 2005 and 2012 piracy activities were rampant in the Horn of Africa and the East Africa Coastal waters. Thereafter, piracy activities prospered in West Africa Gulf of Guinea States. To date the same are still persisting in the Gulf of Guinea Coastal States. The impact brought by African piracy to the shipping industry and maritime transportation at large, have touched a range of nations from developed countries to the developing countries. Because of that, the International and Regional communities set up strategies to fight and repress piracy activities within the Continent. Maritime piracy is a crime and was firstly considered as crime by the customary international law even before codification of the same in 1958 Geneva Convention on the High Seas and later the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) has not set for the punishment of pirates but it has rest to the individual countries to prosecute and punish piracy offenders according to the laws of a particular country. -

The EU's Response to Piracy in the Global Maritime Domain: Are the Lessons Learned in the Horn of Africa a Model for the Gulf of Guinea?

EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies Academic Year 2014-2015 The EU's Response to Piracy in the Global Maritime Domain: Are the Lessons Learned in the Horn of Africa a Model for the Gulf of Guinea? Enrico GUNTHER (DE) – Supervisor: Alyson BAILES Abstract The European Union (EU) is seen as the leading actor in successfully fighting piracy around the Horn of Africa. As a global trade power with strong economic interests, the EU has become aware of the importance of a safe and secure maritime domain following the increase in attacks by Somali pirates from 2006 onwards. The EU Maritime Security Strategy adopted in 2014 provides evidence for this securitisation process. The EU is also challenged by maritime security threats posed by pirates in the Gulf of Guinea. To date, there has been no comprehensive analysis to assess the potential transfer of successful EU instruments from the Horn of Africa to the piracy situation in West African waters. This thesis looks at both current and potential answers of the EU to fight piracy off West African coastlines. Based on qualitative research interviews, lessons learned from the EU’s Comprehensive Approach to East Africa are identified and subsequently applied to the situation in the Gulf of Guinea. The results show that the EU is rather reluctant to use crisis management instruments because it seeks to strengthen responsibility and ownership of the coastal countries. It rather provides financial support and expertise with the objective of establishing a maritime security architecture for the West African waters. Nonetheless, the EU can draw on its successful leadership in international political and military cooperation from around the Horn of Africa in order to make the use of available counter-piracy resources in the Gulf of Guinea more effective.