Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea: EU and International Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

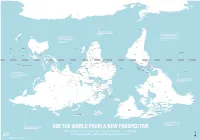

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Addressing the Atlantic's Emerging Security Challenges

34 Addressing the Atlantic’s Emerging Security Challenges Bruno Lété The German Marshall Fund of the United States ABSTRACT As the Atlantic space is expected to continue to play a global role, it is not surprising that nations around the Atlantic have become increasingly concerned about securing the region’s commons at land, at sea, and in the air. In much contrast to the territorial disputes and military tensions defining the Pacific Rim, the Atlantic remains a relatively stable geo-political sphere, largely due to the lack of great power conflict. But the prominence of the region in security and military considerations is rising, especially with the aim to combat illegal activities. This paper identifies three emerging security challenges that may jeopardize the future peace and prosperity of all the countries surrounding the Atlantic Ocean if they are left unresolved. The first draft of this Scientific Paper was presented at the ATLANTIC FUTURE Seminar, Lisbon, 24 April 2015 ATLANTIC FUTURE SCIENTIFIC PAPER 34 Table of contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 3 2. The Atlantic remains a key region in a rapidly changing global system ...................................................................................................... 3 3. Three emerging challenges affect security in the Atlantic ....... 4 4. A pan-Atlantic approach is lacking ...................................................... 9 5. Conclusion .................................................................................................. -

From Operation Serval to Barkhane

same year, Hollande sent French troops to From Operation Serval the Central African Republic (CAR) to curb ethno-religious warfare. During a visit to to Barkhane three African nations in the summer of 2014, the French president announced Understanding France’s Operation Barkhane, a reorganization of Increased Involvement in troops in the region into a counter-terrorism Africa in the Context of force of 3,000 soldiers. In light of this, what is one to make Françafrique and Post- of Hollande’s promise to break with colonialism tradition concerning France’s African policy? To what extent has he actively Carmen Cuesta Roca pursued the fulfillment of this promise, and does continued French involvement in Africa constitute success or failure in this rançois Hollande did not enter office regard? France has a complex relationship amid expectations that he would with Africa, and these ties cannot be easily become a foreign policy president. F cut. This paper does not seek to provide a His 2012 presidential campaign carefully critique of President Hollande’s policy focused on domestic issues. Much like toward France’s former African colonies. Nicolas Sarkozy and many of his Rather, it uses the current president’s predecessors, Hollande had declared, “I will decisions and behavior to explain why break away from Françafrique by proposing a France will not be able to distance itself relationship based on equality, trust, and 1 from its former colonies anytime soon. solidarity.” After his election on May 6, It is first necessary to outline a brief 2012, Hollande took steps to fulfill this history of France’s involvement in Africa, promise. -

The Somali Maritime Space

LEA D A U THORS: C urtis Bell Ben L a wellin CONTRIB UTI NG AU THORS: A l e x andr a A mling J a y Benso n S asha Ego r o v a Joh n Filitz Maisie P igeon P aige Roberts OEF Research, Oceans Beyond Piracy, and Secure Fisheries are programs of One Earth Future http://dx.doi.org/10.18289/OEF.2017.015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS With thanks to John R. Hoopes IV for data analysis and plotting, and to many others who offered valuable feedback on the content, including John Steed, Victor Odundo Owuor, Gregory Clough, Jérôme Michelet, Alasdair Walton, and many others who wish to remain unnamed. Graphic design and layout is by Andrea Kuenker and Timothy Schommer of One Earth Future. © 2017 One Earth Future Stable Seas: Somali Waters | i TABLE OF CONTENTS STABLE SEAS: SOMALI WATERS .......................................................................................................1 THE SOMALI MARITIME SPACE ........................................................................................................2 COASTAL GOVERNANCE.....................................................................................................................5 SOMALI EFFORTS TO PROVIDE MARITIME GOVERNANCE ..............................................8 INTERNATIONAL EFFORTS TO PROVIDE MARITIME GOVERNANCE ..........................11 MARITIME PIRACY AND TERRORISM ...........................................................................................13 ILLEGAL, UNREPORTED, AND UNREGULATED FISHING ....................................................17 ARMS TRAFFICKING -

The North Caucasus: the Challenges of Integration (III), Governance, Elections, Rule of Law

The North Caucasus: The Challenges of Integration (III), Governance, Elections, Rule of Law Europe Report N°226 | 6 September 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Russia between Decentralisation and the “Vertical of Power” ....................................... 3 A. Federative Relations Today ....................................................................................... 4 B. Local Government ...................................................................................................... 6 C. Funding and budgets ................................................................................................. 6 III. Elections ........................................................................................................................... 9 A. State Duma Elections 2011 ........................................................................................ 9 B. Presidential Elections 2012 ...................................................................................... -

Country by Country Reporting

COUNTRY BY COUNTRY REPORTING PUBLICATION REPORT 2018 (REVISED) Anglo American is a leading global mining company We take a responsible approach to the management of taxes, As we strive to deliver attractive and sustainable returns to our with a world class portfolio of mining and processing supporting active and constructive engagement with our stakeholders shareholders, we are acutely aware of the potential value creation we operations and undeveloped resources. We provide to deliver long-term sustainable value. Our approach to tax is based can offer to our diverse range of stakeholders. Through our business on three key pillars: responsibility, compliance and transparency. activities – employing people, paying taxes to, and collecting taxes the metals and minerals to meet the growing consumer We are proud of our open and transparent approach to tax reporting. on behalf of, governments, and procuring from host communities – driven demands of the world’s developed and maturing In addition to our mandatory disclosure obligations, we are committed we make a significant and positive contribution to the jurisdictions in economies. And we do so in a way that not only to furthering our involvement in voluntary compliance initiatives, such which we operate. Beyond our direct mining activities, we create and generates sustainable returns for our shareholders, as the Tax Transparency Code (developed by the Board of Taxation in sustain jobs, build infrastructure, support education and help improve but also strives to make a real and lasting positive Australia), the Responsible Tax Principles (developed by the B Team), healthcare for employees and local communities. By re-imagining contribution to society. -

Geological Evolution of the Red Sea: Historical Background, Review and Synthesis

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277310102 Geological Evolution of the Red Sea: Historical Background, Review and Synthesis Chapter · January 2015 DOI: 10.1007/978-3-662-45201-1_3 CITATIONS READS 6 911 1 author: William Bosworth Apache Egypt Companies 70 PUBLICATIONS 2,954 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Near and Middle East and Eastern Africa: Tectonics, geodynamics, satellite gravimetry, magnetic (airborne and satellite), paleomagnetic reconstructions, thermics, seismics, seismology, 3D gravity- magnetic field modeling, GPS, different transformations and filtering, advanced integrated examination. View project Neotectonics of the Red Sea rift system View project All content following this page was uploaded by William Bosworth on 28 May 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. Geological Evolution of the Red Sea: Historical Background, Review, and Synthesis William Bosworth Abstract The Red Sea is part of an extensive rift system that includes from south to north the oceanic Sheba Ridge, the Gulf of Aden, the Afar region, the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aqaba, the Gulf of Suez, and the Cairo basalt province. Historical interest in this area has stemmed from many causes with diverse objectives, but it is best known as a potential model for how continental lithosphere first ruptures and then evolves to oceanic spreading, a key segment of the Wilson cycle and plate tectonics. -

99 UPWELLING in the GULF of GUINEA Results of a Mathematical

99 UPWELLING IN THE GULF OF GUINEA Results of a mathematical model 2 2 6 5 0 A. BAH Mécanique des Fluides géophysiques, Université de Liège, Liège (Belgium) ABSTRACT A numerical simulation of the oceanic response of an x-y-t two-layer model on the 3-plane to an increase of the wind stress is discussed in the case of the tro pical Atlantic Ocean. It is shown first that the method of mass transport is more suitable for the present study than the method of mean velocity, especially in the case of non-linearity. The results indicate that upwelling in the oceanic equatorial region is due to the eastward propagating equatorially trapped Kelvin wave, and that in the coastal region upwelling is due to the westward propagating reflected Rossby waves and to the poleward propagating Kelvin wave. The amplification due to non- linearity can be about 25 % in a month. The role of the non-rectilinear coast is clearly shown by the coastal upwelling which is more intense east than west of the three main capes of the Gulf of Guinea; furthermore, by day 90 after the wind's onset, the maximum of upwelling is located east of Cape Three Points, in good agree ment with observations. INTRODUCTION When they cross over the Gulf of Guinea, monsoonal winds take up humidity and subsequently discharge it over the African Continent in the form of precipitation (Fig. 1). The upwelling observed during the northern hemisphere summer along the coast of the Gulf of Guinea can reduce oceanic evaporation, and thereby affect the rainfall pattern in the SAHEL region. -

An Economic Impact Assessment of Somali Piracy Epameinondas A. Anastasiadis

Erasmus University Rotterdam MSc in Maritime Economics and Logistics 2011/2012 An Economic Impact Assessment of Somali Piracy By Epameinondas A. Anastasiadis Copyright © Epaminondas A. Anastasiadis Erasmus University Rotterdam Acknowledgements The completion of this Thesis is the final requirement of the Master’s degree in Maritime Economics and Logistics in Erasmus University Rotterdam and marks the conclusion of a very demanding and challenging academic year. During this captivating procedure many people that deserve my gratitude were on my side. Firstly, I would like to state my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisor, Dr. Koen Berden for his valuable assistance, insight and cooperation during the course and for completing this thesis. Many thanks also to the academic staff of MEL for their contribution in expanding my knowledge for the fascinating world of Shipping. Even though I had studied the Piracy phenomenon in the past, it was the spherical information I received over the past months that helped me comprehend its importance and effect on international Shipping and Trade. Additional thanks must also go to my classmates and friends in MEL for their cooperation and friendship during this year. I would also like to thank all my close friends back in Greece for their support and understanding during these months. Finally, my biggest thanks and love to my parents Nikos and Athena as well as to my brother Yannis, for their endless support since day one. I owe you everything. iii Erasmus University Rotterdam Abstract This thesis estimates the macroeconomic effect of Somali piracy through the measurement and analysis of the costs that the phenomenon imposes on container shipping. -

Chirac and ‘La Franc¸Afrique’: No Longer a Family Affair Tony Chafer

Modern & Contemporary France Vol. 13, No. 1, February 2005, pp. 7–23 Chirac and ‘la Franc¸afrique’: No Longer a Family Affair Tony Chafer Since political independence, France has maintained a privileged sphere of influence—the so-called ‘pre´ carre´’—in sub-Saharan Africa, based on a series of family-like ties with its former colonies. The cold war provided a favourable environment for the development of this special relationship, as the USA saw the French presence in this part of the world as useful for the containment of Communism. However, following the end of the cold war, France has had to adapt to a new international policy environment that is more competitive and less conducive to the maintenance of such family-like ties. This article charts the evolution of Franco-African relations in an era of globalisation, as French governments have undertaken a hesitant process of policy adaptation since the mid-1990s. Unlike decolonisation in Indochina and Algeria, the transfer of power in Black Africa was largely peaceful; as a result, there was no rupture of relations with the former colonial power. On the contrary, the years after independence were marked by an intensification of the links with France. Official rhetoric often referred to the great Franco-African family and the term ‘la Franc¸afrique’ testified to a symbiotic relationship in which ‘Africa is experienced in French representations as a natural extension where the Francophone world and Francophilia merge’ (Bourmaud, 2000). In fact, a wide variety of terms have been coined to describe -

Influence of Pirates' Activities on Maritime Transport in the Gulf of Aden Region

International Journal Volume 6 on Marine Navigation Number 1 and Safety of Sea Transportation March 2012 Influence of Pirates' Activities on Maritime Transport in the Gulf of Aden Region D. Duda & K. Wardin Polish Naval University, Gdynia, Poland ABSTRACT: Modern piracy is one of the items appearing on the seas, which has a great impact on maritime transport in many regions of the world. Changes that happened at the end of XX and beginning of XXI centu- ry became significant in the renaissance of piracy. The problem is present in many parts of the world but it become a real threat in year 2008 around a small country of Somalia and in the area called the Horn of Africa especially in the region of Gulf of Aden. Because international waters are very important for maritime transport so pirates’ attacks have great influence over this transport and on international community. 1 PIRACY – DEFINITION AND MAIN AREAS ternational Maritime Bureau (IMB) and according to OF PIRATES’ ACTIVITIES IMB piracy is defined as: an act of boarding or at- tempting to board any ship with the intent to commit Piracy is an activity known and grown for thousands theft or any other crime and with the intent or capa- of years. At present in many parts of the world it is bility to use force in the furtherance of that act6. treated as a type of legacy or rather part of tradition As mentioned before, the problem is not equally and so also gladly continued by the population who the same in all places where piracy flourishes in the is experiencing poverty and hunger. -

Is Map Is Just As Accurate As the One We're All Used To

ROSS SEA WEDDELL SEA AMUNDSEN SEA ANTARCTICA BELLINGSHAUSEN SEA AMERY ICE SHELF SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SCOTIA SEA DRAKE PASSAGE FALKLAND ISLANDS Stanley (U.K.) THE RATIO OF LAND TO WATER IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE BY THE TIME EUROPEANS ADOPTED IS 1 TO 5 THE NORTH-POINTING COMPASS, PTOLEMY WAS A HELLENIC Wellington THEY WERE ALREADY EXPERIENCED NEW TASMAN SEA ZEALAND CARTOGRAPHER WHOSE WORK CHILE IN NAVIGATING WITH REFERENCE TO IN THE SECOND CENTURY A.D. ARGENTINA THE NORTH STAR Canberra Buenos Santiago GREAT AUSTRALIAN BIGHT POPULARIZED NORTH-UP Montevideo Aires SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN URUGUAY ORIENTATION SOUTH AFRICA Maseru LESOTHO SWAZILAND Mbabane Maputo Asunción AUSTRALIA Pretoria Gaborone NEW Windhoek PARAGUAY TONGA Nouméa CALEDONIA BOTSWANA Saint Denis NAMIBIA Nuku’Alofa (FRANCE) MAURITIUS Port Louis Antananarivo MOZAMBIQUE CHANNEL ZIMBABWE Suva Port Vila MADAGASCAR VANUATU MOZAMBIQUE Harare La Paz INDIAN OCEAN Brasília LAKE SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN FIJI Lusaka TITICACA CORAL SEA GREAT GULF OF BARRIER CARPENTARIA Lilongwe ZAMBIA BOLIVIA FRENCH POLYNESIA Apia REEF LAKE (FRANCE) SAMOA TIMOR SEA COMOROS NYASA ANGOLA Lima Moroni MALAWI Honiara ARAFURA SEA BRAZIL TIMOR LESTE PERU Funafuti SOLOMON Port Dili Luanda ISLANDS Moresby LAKE Dodoma TANGANYIKA TUVALU PAPUA Jakarta SEYCHELLES TANZANIA NEW GUINEA Kinshasa Victoria BURUNDI Bujumbura DEMOCRATIC KIRIBATI Brazzaville Kigali REPUBLIC LAKE OF THE CONGO SÃO TOMÉ Nairobi RWANDA GABON ECUADOR EQUATOR INDONESIA VICTORIA REP. OF AND PRINCIPE KIRIBATI EQUATOR