Articles from the Free Tropo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addressing the Atlantic's Emerging Security Challenges

34 Addressing the Atlantic’s Emerging Security Challenges Bruno Lété The German Marshall Fund of the United States ABSTRACT As the Atlantic space is expected to continue to play a global role, it is not surprising that nations around the Atlantic have become increasingly concerned about securing the region’s commons at land, at sea, and in the air. In much contrast to the territorial disputes and military tensions defining the Pacific Rim, the Atlantic remains a relatively stable geo-political sphere, largely due to the lack of great power conflict. But the prominence of the region in security and military considerations is rising, especially with the aim to combat illegal activities. This paper identifies three emerging security challenges that may jeopardize the future peace and prosperity of all the countries surrounding the Atlantic Ocean if they are left unresolved. The first draft of this Scientific Paper was presented at the ATLANTIC FUTURE Seminar, Lisbon, 24 April 2015 ATLANTIC FUTURE SCIENTIFIC PAPER 34 Table of contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 3 2. The Atlantic remains a key region in a rapidly changing global system ...................................................................................................... 3 3. Three emerging challenges affect security in the Atlantic ....... 4 4. A pan-Atlantic approach is lacking ...................................................... 9 5. Conclusion .................................................................................................. -

Akosombo Dam : Growth and Suffering

Newsletter on water and environment THE CONTRIBUTION OF BIG WATER INFRASTRUCTURES TO THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF COUNTRIES IN WEST AFRICA AKOSOMBO DAM : GROWTH AND SUFFERING More than 40 years of welfare ensured by the dam 44THTH REGIONALREGIONAL WESTWEST AFRICANAFRICAN JOURNALISTSJOURNALISTS WORKSHOPWORKSHOP CONTENTS DAMS & COMMUNITIES Newsletter on water and environment When Dams Become A Curse Page 4 Managing Editor Ghana’s Jewel and the forgotten ones Dam MOGBANTE Page 6 APAASO- What A lure! Editor in chief Page 6 Near Hydro Power Plant But Living in Darkness Sidi COULIBALY Page 8 AkOSOMBO HYDROPOWER DAM: Editing board No joy at Apaaso! HOUNGBADJI Leonce (Benin) Page 9 Germaine BONI (Côte d’Ivoire) VRA talks back Emilia ENNIN (Ghana) Page 9 William Freeman (Sierra Leone) DAMS AND REGIONAL COOPERATION Frederick ASIAMAH (Ghana) Large dams: sources of disputes and linkages Dora Asare (Ghana) Page 10 Gertrude ANKAH (Ghana) The Akosombo Dam, a symbol of regional integration Edmund Smith ASANTE (Ghana) Page 11 Dzifa AZUMAH (Ghana) HUMOUR Mohamed M. JALLOW (The Gambia) Akosombo, a town created by a dam Alain TOSSOUNON (Benin) Page 11 Abdoulaye THIAM (Senegal) Abdoulaye Doumbouya, Representative of the Niger Basin Authority (NBA) TONAKPA Constant (Benin) “No problem if every country plays its role” Cheick B. SIGUE (Burkina Faso) Page 12 Kounkou MARA (Rep. Guinea) DAMS CONSTRUCTION Assane KONE (Mali) Akosombo Dam Too Strong for Earthquake? Obi Amako (Nigeria) Page 13 Becce Duho (Ghana) Construction of New Dams Michael SIMIRE (Nigeria) ...Government Urged to Take Second Look at Impacts Sani ABOUBACAR (Niger) Page 14 Edem GADEGBEKU (Togo) Interview Tamsir Ndiaye, Coordinator of the African Network of Basin Organizations Illustrations “Dams are issues of major stakes” TONAKPA Constant (Benin) Page 16 Obi Amako (Nigeria) NEWS REPORT Capacity Building Workshop for West African Journalists Held in Accra Photos Page 17 S. -

99 UPWELLING in the GULF of GUINEA Results of a Mathematical

99 UPWELLING IN THE GULF OF GUINEA Results of a mathematical model 2 2 6 5 0 A. BAH Mécanique des Fluides géophysiques, Université de Liège, Liège (Belgium) ABSTRACT A numerical simulation of the oceanic response of an x-y-t two-layer model on the 3-plane to an increase of the wind stress is discussed in the case of the tro pical Atlantic Ocean. It is shown first that the method of mass transport is more suitable for the present study than the method of mean velocity, especially in the case of non-linearity. The results indicate that upwelling in the oceanic equatorial region is due to the eastward propagating equatorially trapped Kelvin wave, and that in the coastal region upwelling is due to the westward propagating reflected Rossby waves and to the poleward propagating Kelvin wave. The amplification due to non- linearity can be about 25 % in a month. The role of the non-rectilinear coast is clearly shown by the coastal upwelling which is more intense east than west of the three main capes of the Gulf of Guinea; furthermore, by day 90 after the wind's onset, the maximum of upwelling is located east of Cape Three Points, in good agree ment with observations. INTRODUCTION When they cross over the Gulf of Guinea, monsoonal winds take up humidity and subsequently discharge it over the African Continent in the form of precipitation (Fig. 1). The upwelling observed during the northern hemisphere summer along the coast of the Gulf of Guinea can reduce oceanic evaporation, and thereby affect the rainfall pattern in the SAHEL region. -

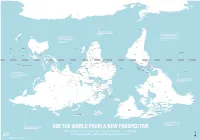

Is Map Is Just As Accurate As the One We're All Used To

ROSS SEA WEDDELL SEA AMUNDSEN SEA ANTARCTICA BELLINGSHAUSEN SEA AMERY ICE SHELF SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SCOTIA SEA DRAKE PASSAGE FALKLAND ISLANDS Stanley (U.K.) THE RATIO OF LAND TO WATER IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE BY THE TIME EUROPEANS ADOPTED IS 1 TO 5 THE NORTH-POINTING COMPASS, PTOLEMY WAS A HELLENIC Wellington THEY WERE ALREADY EXPERIENCED NEW TASMAN SEA ZEALAND CARTOGRAPHER WHOSE WORK CHILE IN NAVIGATING WITH REFERENCE TO IN THE SECOND CENTURY A.D. ARGENTINA THE NORTH STAR Canberra Buenos Santiago GREAT AUSTRALIAN BIGHT POPULARIZED NORTH-UP Montevideo Aires SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN URUGUAY ORIENTATION SOUTH AFRICA Maseru LESOTHO SWAZILAND Mbabane Maputo Asunción AUSTRALIA Pretoria Gaborone NEW Windhoek PARAGUAY TONGA Nouméa CALEDONIA BOTSWANA Saint Denis NAMIBIA Nuku’Alofa (FRANCE) MAURITIUS Port Louis Antananarivo MOZAMBIQUE CHANNEL ZIMBABWE Suva Port Vila MADAGASCAR VANUATU MOZAMBIQUE Harare La Paz INDIAN OCEAN Brasília LAKE SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN FIJI Lusaka TITICACA CORAL SEA GREAT GULF OF BARRIER CARPENTARIA Lilongwe ZAMBIA BOLIVIA FRENCH POLYNESIA Apia REEF LAKE (FRANCE) SAMOA TIMOR SEA COMOROS NYASA ANGOLA Lima Moroni MALAWI Honiara ARAFURA SEA BRAZIL TIMOR LESTE PERU Funafuti SOLOMON Port Dili Luanda ISLANDS Moresby LAKE Dodoma TANGANYIKA TUVALU PAPUA Jakarta SEYCHELLES TANZANIA NEW GUINEA Kinshasa Victoria BURUNDI Bujumbura DEMOCRATIC KIRIBATI Brazzaville Kigali REPUBLIC LAKE OF THE CONGO SÃO TOMÉ Nairobi RWANDA GABON ECUADOR EQUATOR INDONESIA VICTORIA REP. OF AND PRINCIPE KIRIBATI EQUATOR -

GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE and POPULATION Ghana Is Situated on the West Coast of Africa with a Total Area of 238 540 Km2

1 Ghana GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE AND POPULATION Ghana is situated on the west coast of Africa with a total area of 238 540 km2. The country has a north-south extent of about 670 km and a maximum east-west extent of about 560 km. It shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to the east. To the south are the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean. The country is divided into 10 administrative regions. The topography is predominantly undulating and of low relief with slopes of less than 1 percent. Despite the gentle slopes, about 70 percent of the country is subject to moderate to severe sheet and gully erosion. The highest elevation in Ghana, Mount Afadjato in the Akwapim-Togo Ranges, rises 880 metres above sea level. There are five distinct geographical regions: • The low plains, stretching across the southern part of the country. • The Ashanti Uplands, stretching from the Côte d’Ivoire border in the west to the elevated edge of the Volta Basin in the east. • The Akwapim-Togo Ranges in the eastern part of the country consist of a generally rugged complex of folded strata, with many prominent heights composed of volcanic rock. The ranges begin west of Accra and continue in a northeasterly direction, finally crossing the border into Togo. • The Volta Basin occupies the central part of Ghana and covers about 45 percent of the nation’s total area. The basin is characterized by poor soil, generally of Voltaian sandstone. • The high plains in the northern and northwestern part of Ghana, outside the Volta Basin, consist of a dissected plateau. -

195 the Gulf of Guinea

THE GULF OF GUINEA: THE NEW DANGER ZONE Africa Report N°195 – 12 December 2012 Translation from French TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. A STRATEGIC REGION IN THE GRIP OF INSECURITY ...................................... 2 A. RENEWED STRATEGIC INTEREST IN NATURAL RESOURCES .......................................................... 2 B. A CONTEXT FAVOURABLE TO MARITIME CRIME ......................................................................... 3 C. WEAK MARITIME POLICIES .......................................................................................................... 4 III. NIGERIA: EPICENTRE OF VIOLENCE AT SEA ...................................................... 6 A. POOR GOVERNANCE AND MARITIME CRIME ................................................................................ 6 1. A leaky oil sector ......................................................................................................................... 6 2. The rise in economic crime .......................................................................................................... 7 3. State capacity hampered by corruption ........................................................................................ 8 4. The Niger Delta ........................................................................................................................... -

4 European Policy and Energy Interests – Challenges from the Gulf of Guinea ␣

CHAPTER I OIL POLICY IN THE GULF OF GUINEA 4 European Policy and Energy Interests – Challenges from the Gulf of Guinea ␣ By Lutz Neumann 1. Introduction ␣ The Gulf of Guinea has great oil and gas potential. While predictions on Africa should be made with some care, analysts and representatives of the oil industry appear to agree that the region belongs to those areas where production will rapidly increase in the coming years and decades. Output figures of the chief oil- producing countries, Nigeria and Angola, are expected to double or triple within the next decade and thus will cause certain dynamics on the shaping of trade movements (see table 1). Table 1: Projected Oil Production of Gulf of Guinea 2005-2030 (in b/d) 2005 2010 2015 2030 Nigeria 2,719,000 3,042,000 3,729,000 4,422,000 Angola 1,098,000 2,026,000 2,549,000 3,288,000 Equatorial-Guinea 313,000 466,000 653,000 724,000 Congo (Brazzaville) 285,000 300,000 314,000 327,000 Gabon 303,000 291,000 279,000 269,000 Côte d’Ivoire 43,000 71,000 83,000 94,000 Cameroun 84,000 72,000 66,000 61,000 Congo (Kinshasa) 30,000 33,000 30,000 25,000 Ghana 11,000 16,000 20,000 23,000 Total Africa 9,936,000 12,059,000 13,975,000 16,242,000 Source: EIA, U.S. Department of Energy.␣ FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG 59 OIL POLICY IN THE GULF OF GUINEA CHAPTER I The African countries along the Atlantic coast represent a growing supplier region. -

Influence of the Gulf of Guinea Coastal and Equatorial Upwellings on the Precipitations Along Its Northern Coasts During the Boreal Summer Period

Asian Journal of Applied Sciences 4 (3): 271-285, 2011 ISSN 1996-3343 I DOI: 10.3923/ajaps.2011.271.285 © 2011 Knowledgia Review, Malaysia Influence of the Gulf of Guinea Coastal and Equatorial Upwellings on the Precipitations along its Northern Coasts during the Boreal Summer Period 'K.E. Ali, 'K.Y. Kouadio, 'E.-P. Zahiri, 'A. Aman, 'A.P. Assamoi and 2B. Bourles 'LAPAMF, Universite de Cocody-Abidjan BP 231 Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire 2IRD/LEGOS-CRHOB, Representation !RD, 08 BP 841 Cotonou, Republique du Benin Corresponding Author: Angora Aman, Universite de Cocody-Abidjan 22 BP 582 Abidjan 22, LAPA-MF, UFR-SSMT, Cote d'Ivoire Tel: (225) 07 82 77 52 Fax: (225) 22 44 14 07 ABSTRACT The Gulf of Guinea (GG) is an area where a seasonal upwelling takes place, along the equator and its northern coasts between Benin and Cote d'Ivoire. The coastal upwelling has a real impact on the local yet documented biological resources. However, climatic impact studies of this seasonal upwelling are paradoxically very rare and disseminated and this impact is still little known, especially on the potential part played by the upwelling onset on the regional precipitation in early boreal summer. This study shows that coastal precipitations of the July-September period are correlated by both the coastal and equatorial sea-surface temperatures (SSTS). This correlation results in a decrease or a rise of rainfall when the SSTs are abnormally cold or warm respectively. The coastal areas that are more subject to coastal and equatorial SSTs influence are located around the Cape Three Points, where the coastal upwelling exhibits the maximum of amplitude. -

Atlantic Ocean Equatorial Currents

188 ATLANTIC OCEAN EQUATORIAL CURRENTS ATLANTIC OCEAN EQUATORIAL CURRENTS S. G. Philander, Princeton University, Princeton, Centered on the equator, and below the westward NJ, USA surface Sow, is an intense eastward jet known as the Equatorial Undercurrent which amounts to a Copyright ^ 2001 Academic Press narrow ribbon that precisely marks the location of doi:10.1006/rwos.2001.0361 the equator. The undercurrent attains speeds on the order of 1 m s\1 has a half-width of approximately Introduction 100 km; its core, in the thermocline, is at a depth of approximately 100 m in the west, and shoals to- The circulations of the tropical Atlantic and PaciRc wards the east. The current exists because the west- Oceans have much in common because similar trade ward trade winds, in addition to driving divergent winds, with similar seasonal Suctuations, prevail westward surface Sow (upwelling is most intense at over both oceans. The salient features of these circu- the equator), also maintain an eastward pressure lations are alternating bands of eastward- and west- force by piling up the warm surface waters in the ward-Sowing currents in the surface layers (see western side of the ocean basin. That pressure force Figure 1). Fluctuations of the currents in the two is associated with equatorward Sow in the thermo- oceans have similarities not only on seasonal but cline because of the Coriolis force. At the equator, even on interannual timescales; the Atlantic has where the Coriolis force vanishes, the pressure force a phenomenon that is the counterpart of El Ninoin is the source of momentum for the eastward Equa- the PaciRc. -

Open Whole.Kad.Final3re.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Earth and Mineral Sciences MANAGING WATER RESOURCES UNDER CLIMATE VARIABILITY AND CHANGE: PERSPECTIVES OF COMMUNITIES IN THE AFRAM PLAINS, GHANA A Thesis in Geography by Kathleen Ann Dietrich © 2008 Kathleen Ann Dietrich Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2008 The thesis of Kathleen Ann Dietrich was reviewed and approved* by the following: Petra Tschakert Assistant Professor of Geography Alliance for Earth Sciences, Engineering, and Development in Africa Thesis Adviser C. Gregory Knight Professor of Geography Karl Zimmerer Professor of Geography Head of the Department of Geography *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Climate variability and change alter the amount and timing of water resources available for rural communities in the Afram Plains district, Ghana. Given the fact that the district has been experiencing a historical and multi-scalar economic and political neglect, its communities face a particular vulnerability for accessing current and future water resources. Therefore, these communities must adapt their water management strategies to both future climate change and the socio-economic context. Using participatory methods and interviews, I explore the success of past and present water management strategies by three communities in the Afram Plains in order to establish potentially effective responses to future climate change. Currently, few strategies are linked to climate variability and change; however, the methods and results assist in giving voice to the participant communities by recognizing, sharing, and validating their experiences of multiple climatic and non-climatic vulnerabilities and the past, current, and future strategies which may enhance their adaptive capacity. -

Towards a National Ocean Policy in Sao Tome And

TOWARDS A NATIONAL OCEAN POLICY IN SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE Mé-Chinhô Costa Alegre The United Nations-Nippon Foundation Fellowship Programme 2009 - 2010 DIVISION FOR OCEAN AFFAIRS AND THE LAW OF THE SEA OFFICE OF LEGAL AFFAIRS, THE UNITED NATIONS NEW YORK, 2009 DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Sao Tome and Principe, the United Nations, the Nippon Foundation of Japan, or the University of West Indies. © 2009 Me-Chinho Costa Alegre. All rights reserved. - i - Abstract The Oceans role to Earth’s environment is broadly recognized and thus there is a growing awareness on environment issues in order to secure preservation of marine resources, food security, sustainability of life at sea and cope with the effects of climate change. Considering that Sao Tome and Principe is a Small Island Developing State (SIDS), a attention will be given to the strategies, policies, legal and institutional approaches among the SIDS around the world and particularly in the Caribbean Region, paying special attention to Barbados experience. The report will consider too the strong pressure on coastal land for construction, tourism developments and other economic activities. The report addresses these issues with reference to the predictable constraint of limited human and financial resources typical of SIDS. In addition, international cooperation among SIDS will be examined in order to understand the Regional integrated policies and strategies needed to tackle common concerns and improve efficiency in the application of resources to implement international instruments. The concept of a Large Marine Ecosystem approach is considered in this analysis of regional cooperation. -

Table 2. Geographic Areas, and Biography

Table 2. Geographic Areas, and Biography The following numbers are never used alone, but may be used as required (either directly when so noted or through the interposition of notation 09 from Table 1) with any number from the schedules, e.g., public libraries (027.4) in Japan (—52 in this table): 027.452; railroad transportation (385) in Brazil (—81 in this table): 385.0981. They may also be used when so noted with numbers from other tables, e.g., notation 025 from Table 1. When adding to a number from the schedules, always insert a decimal point between the third and fourth digits of the complete number SUMMARY —001–009 Standard subdivisions —1 Areas, regions, places in general; oceans and seas —2 Biography —3 Ancient world —4 Europe —5 Asia —6 Africa —7 North America —8 South America —9 Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds —001–008 Standard subdivisions —009 History If “history” or “historical” appears in the heading for the number to which notation 009 could be added, this notation is redundant and should not be used —[009 01–009 05] Historical periods Do not use; class in base number —[009 1–009 9] Geographic treatment and biography Do not use; class in —1–9 —1 Areas, regions, places in general; oceans and seas Not limited by continent, country, locality Class biography regardless of area, region, place in —2; class specific continents, countries, localities in —3–9 > —11–17 Zonal, physiographic, socioeconomic regions Unless other instructions are given, class