Trust and Self-Trust in Leadership Identity Constructions: a Qualitative Exploration of Narrative Ecology in the Discursive Aftermath of Heroic Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Internship Reflection Book

i CONTENTS 1 ABOUT THE REFLECTION ESSAYS Butzin Internship Fund 19 Spending a Summer in Gratitude for Service Dogs 12 Legal Internship 2 A LOOK AT OUR INTERNSHIP FUNDS Sophia Myers ’21 Doing Investigative Work Nick Pomper ’21 20 A Summer of Archival Work 7 REFLECTION ESSAYS in Northfield and Rice County (listed alphabetically by fund, then student) Center for Community and Hannah Zhukovsky ’21 Civic Engagement (CCCE) Abeona Endowed Fund Fellowships Chang-Lan Endowed Fund for International Internships 13 An Internship at the YMCA 21 Researching Protein Engineering 8 Learning about the Film Industries Reveals the Importance in a Lab and Overcoming of France and the United States of Social Connections Research Challenges Alison Hong ’22 Carly Bell ’21 Yiqiu Zhang ’22 9 Autism Research 14 Understanding Disparate in a Virtual Internship Food Access in Rice County Sara Liu ’22 Emily Hall ’21 PICTURED ON COVER American Studies Grant 16 Serving Up much more than Top row: AARON FORMAN ’21, Food in a Community Food Shelf HODAN MOHAMED ’22, 10 Seeing Behind the Curtain MAYA ROGERS ’22, Jack Johnson ’21 of a Political Campaign Office ASTRID PETROPOULOS ’23 Rebecca McCartney ’21 17 The Kaleidoscopic of Richness and Second row: KRISTIN MIYAGI ’22, Diversity of Life in Rice County NARIAH SIMS ’21, MADI SMITH ’22, 11 Supporting Tribal Alexander Kucich ’21 MAX VALE ’22 Sovereignty and Boosting Indigenous Rights 18 Interning at a Food Shelf, Third row: SUAD MOHAMED ’23, TREVOR HUGHES ’21, Thomas White ’22 and Confirming an Interest ANWESHA MUKHERJI ’23, -

Negotiating Musicianship Live Weider Ellefsen

Ellefsen Weider Live Live Weider Ellefsen In this ethnographic case-study of a Norwegian upper secondary music musicianship Negotiating programme – “Musikklinja” – Live Weider Ellefsen addresses questions of Negotiating musicianship subjectivity, musical learning and discursive power in music educational practices. Applying a conceptual framework based on Foucault’s discourse The constitution of student subjectivities theory and Butler’s theory of (gender) performativity, she examines how the young people of Musikklinja achieve legitimate positions of music student- in and through discursive practices of hood in and through Musikklinja practices of musicianship, across a range of sites and activities. In the analyses, Ellefsen shows how musical learn- musicianship in “Musikklinja” ers are constituted as they learn, subjecting themselves to and perform- ing themselves along relations of power and knowledge that also work as means of self-understanding and discursive mastery. The study’s findings suggest that dedication, entrepreneurship, compe- tence, specialization and connoisseurship are prominent discourses at play in Musikklinja. It is by these discourses that the students are socially and institutionally identified and addressed as music students, and it is by understanding themselves in relation to these discourses that they come to be music student subjects. The findings also propose that a main charac- teristic in the constitution of music student subjectivity in Musikklinja is the appropriation of discourse, even where resistance can be noted. However, within the overall strategy of accepting and appropriating discourses of mu- sicianship, students subtly negotiate – adapt, shift, subvert – the available discourses in ways that enable and empower their discursive legitimacy. Musikklinja constitutes an important educational stepping stone to higher music education and to professional musicianship in Norway. -

Your Life 25 Healthy Can You Eat Diet Tips Hemp?

www.govita.com.au ISSUE 28 2012 • $5.95 (GST INC) overcome exhaustion and energise top your life 25 healthy can you eat diet tips hemp? Diana Rouvas TheT Voice Finalist in profi le Like us on facebook.com/GoVitaAustralia for your chance to WIN one of 50 Summer Wellness Packs valued at $300 " " " " ! " # " welcome this issue Energise As the ‘crazy time’ of year approaches yet again, we know you will love our article line-up this issue! We have your life included articles that cover; how to prepare yourself for the party season, our top 25 healthy diet tips, how to Secret energise your life and summer skincare fi xes – all specially women’s written to help you during this busy time of year. We have herbs also included some top gift ideas if you are struggling with suggestions for interesting and useful gifts. Chinese herbs can replenish Herbs to help manage PMS your energy levels and Also remember that you need looking after too, so make and menopausal symptoms. sure you don’t skip exercise, sleep, healthy foods or prevent burnout. supplements! All can make a difference to whether you just survive or thrive these holidays! We are very excited to tell all our readers that they can Go nuts for Diana Rouvas now follow Go Vita on Facebook at www.facebook.com/ coconuts in profi le GoVitaAustralia - turn to the Go Guide for details on how to like us on Facebook and go in the draw to win one of 50 Summer Wellness packs valued at $300 each. -

Daniel Drake, M

PIONEER LIFE IN KENTUCKY. A SERIES OF Reminiscential Letters FROM DANIEL DRAKE, M. D., OF CINCINNATI, TO HIS CHILDREN. Edited with Notes and a Biographical Sketch hy his San, CHARLES D. DRAKE. CINCINNATI: ROBERT CLARKE & CO. J 870. 0, ~ DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF My Mother. CONTENTS. .. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Vll. LETTER I. Ancestors of Doctor Drake-His Birth-Emigration of the Family from New Jersey to Kentucky-History of the Family during Daniel's first Three Years. I LETTER II. History of Family continued, from Daniel's Third year until his Ninth-Removal from first Cabin., by the Roadside., to · another in the Woods. 17 LETTER III. Employments of the Early Settlers-Their modes of Life and Labors-Cultivation of Indian Corn-Wheat-Flax, etc. Corn Husking-Log Rollings, etc.-Daniel's Labors as a Farm Boy from Seven to Fifteen Years of Age. 39 LETTER IV. Farm-Boy Labors-Particularly in the care of Stock ; Sugar Making, etc,, etc. 71 LETTER V. Maternal and Domestic Influences-Domestic Labors (indoors) from Ninth to Fifteenth Year-Broom l\1aking-Soap Making-Cheese Making-Ch urning-Hog Killing-Sausage Making-Dyeing-Sheep Washing and Shearing-Wool Carding Spinning, etc. - · 87 LETTER VI. Boy Delight in the Aspects of Nature-A Thunder storm-Squirrel Hunting-Bee Hunting-Nut Gathering-Bene ficial Influences of Country Life and Familiarity with Nature upon the Young. I l 7 LETTER VII. School Influences -Log-Cabin Schools and School- Masters-Methods of Teaching-School Amusements, etc. 141 LETTER VIII. Religious and Social Influences. 175 LETTER IX. Nature and Extent of Acquirements, at the Time of Commencing the Study of Medicine-Journey from Mayslick to Cincinnati-Begins the Study of Medicine. -

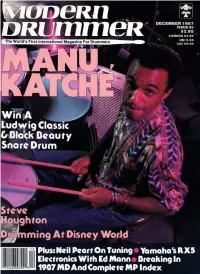

December 1987

VOLUME 11, NUMBER 1 2, ISSUE 98 Cover Photo by Jaeger Kotos EDUCATION IN THE STUDIO Drumheads And Recording Kotos by Craig Krampf 38 SHOW DRUMMERS' SEMINAR Jaeger Get Involved by by Vincent Dee 40 KEYBOARD PERCUSSION Photo In Search Of Time by Dave Samuels 42 THE MACHINE SHOP New Sounds For Your Old Machines by Norman Weinberg 44 ROCK PERSPECTIVES Ringo Starr: The Later Years by Kenny Aronoff 66 ELECTRONIC INSIGHTS Percussive Sound Sources And Synthesis by Ed Mann 68 TAKING CARE OF BUSINESS Breaking In MANU KATCHE by Karen Ervin Pershing 70 One of the highlights of Peter Gabriel's recent So album and ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC tour was French drummer Manu Katche, who has gone on to Two-Surface Riding: Part 2 record with such artists as Sting, Joni Mitchell, and Robbie by Rod Morgenstein 82 Robertson. He tells of his background in France, and explains BASICS why Peter Gabriel is so important to him. Thoughts On Tom Tuning by Connie Fisher 16 by Neil Peart 88 TRACKING DRUMMING AT DISNEY Studio Chart Interpretation by Hank Jaramillo 100 WORLD DRUM SOLOIST When it comes to employment opportunities, you have to Three Solo Intros consider Disney World in Florida, where 45 to 50 drummers by Bobby Cleall 102 are working at any given time. We spoke to several of them JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP about their working conditions and the many styles of music Fast And Slow Tempos that are represented there, by Peter Erskine 104 by Rick Van Horn 22 CONCEPTS Drummers Are Special People STEVE HOUGHTON by Roy Burns 116 He's known for his big band work with Woody Herman, EQUIPMENT small-group playing with Scott Henderson, and his teaching at SHOP TALK P.I.T. -

Maria Lundberg

Trust and Self-trust in Leadership Identity Constructions A Qualitative Exploration of Narrative Ecology in the Discursive Aftermath of Heroic Discourse Lundberg, Maria Document Version Final published version Publication date: 2019 License CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Lundberg, M. (2019). Trust and Self-trust in Leadership Identity Constructions: A Qualitative Exploration of Narrative Ecology in the Discursive Aftermath of Heroic Discourse. Copenhagen Business School [Phd]. PhD series No. 20.2019 Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 COPENHAGEN BUSINESS SCHOOL OF HEROIC DISCOURSE ECOLOGY IN THE DISCURSIVE AFTERMATH OF NARRATIVE EXPLORATION IN LEADERSHIP IDENTITY CONSTRUCTIONS - A QUALITATIVE TRUST AND SELF-TRUST SOLBJERG PLADS 3 DK-2000 FREDERIKSBERG DANMARK WWW.CBS.DK ISSN 0906-6934 Print ISBN: 978-87-93744-82-0 Online ISBN: 978-87-93744-83-7 Maria Lundberg TRUST AND SELF-TRUST IN LEADERSHIP IDENTITY CONSTRUCTIONS A QUALITATIVE EXPLORATION OF NARRATIVE ECOLOGY IN THE DISCURSIVE AFTERMATH -

Australian Chamber Music with Piano

Australian Chamber Music with Piano Australian Chamber Music with Piano Larry Sitsky THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Sitsky, Larry, 1934- Title: Australian chamber music with piano / Larry Sitsky. ISBN: 9781921862403 (pbk.) 9781921862410 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Chamber music--Australia--History and criticism. Dewey Number: 785.700924 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Preface . ix Part 1: The First Generation 1 . Composers of Their Time: Early modernists and neo-classicists . 3 2 . Composers Looking Back: Late romantics and the nineteenth-century legacy . 21 3 . Phyllis Campbell (1891–1974) . 45 Fiona Fraser Part 2: The Second Generation 4 . Post–1945 Modernism Arrives in Australia . 55 5 . Retrospective Composers . 101 6 . Pluralism . 123 7 . Sitsky’s Chamber Music . 137 Edward Neeman Part 3: The Third Generation 8 . The Next Wave of Modernism . 161 9 . Maximalism . 183 10 . Pluralism . 187 Part 4: The Fourth Generation 11 . The Fourth Generation . 225 Concluding Remarks . 251 Appendix . 255 v Acknowledgments Many thanks are due to the following. -

Portraits of Vocal Psychotherapists: Singing As a Healing Influence for Change and Transformation

PORTRAITS OF VOCAL PSYCHOTHERAPISTS: SINGING AS A HEALING INFLUENCE FOR CHANGE AND TRANSFORMATION SUSAN SUMMERS A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Ph.D. in Leadership and Change Program of Antioch University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2014 This is to certify that the Dissertation entitled: PORTRAITS OF VOCAL PSYCHOTHERAPISTS: SINGING AS A HEALING INFLUENCE FOR CHANGE AND TRANSFORMATION prepared by Susan Summers Is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Leadership and Change. Approved by: ______________________________________________________________ Carolyn Kenny, Ph.D., Chair date ______________________________________________________________ Jon Wergin, Ph.D., Committee Member date ______________________________________________________________ Sanne Storm, Ph.D., Committee Member date ______________________________________________________________ Randi Rolvsjord, Ph.D., External Reader date Copyright 2014 Susan Summers All rights reserved Acknowledgements My heartfelt and eternal gratitude to Carolyn, my committee chair, faculty advisor, mentor, music therapy colleague, fellow Canadian in every way that counts, and long-time friend. Thanks for your supportive and nurturing encouragement, clarification, support, wisdom, dedication, guidance, and friendship over the past five years of this doctoral journey. You have inspired me to be my best self, to believe and have faith that I could do this, to give voice to what I know, and to value my intuitive knowing. Your generosity, love and giving spirit has made this journey a healing one for me. I honour and thank you for shining your light and showing us the way, having the courage to lead change by being who you are and staying true to self. To my committee members: Jon, I thank you for your wonderful teaching during the program, for your dedication and guidance in my proposal and dissertation, and for having ongoing curiosity and offering gentle support throughout my time at Antioch. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

At Least You Look Good

AT LEAST YOU LOOK GOOD LEARNING TO GLOW THROUGH WHAT YOU GO THROUGH KATIE DEPAOLA Copyright © 2020 by Katie DePaola All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. ISBN: 978-1-951407-35-3 Paperback ISBN: 978-1-951407-36-0 eBook DISCLAIMER This work is non-!ction and, as such, re"ects the author’s memory of the experiences. Many of the names and identi‐ fying characteristics of the individuals featured in this book have been changed to protect their privacy and certain indi‐ viduals are composites. Dialogue and events have been recreated; in some cases, conversations were edited to convey their substance rather than written exactly as they occurred. CONTENTS Introduction ix PART ONE BASICS 1. Choosing Miracles 3 2. Fear of Glowing 5 3. The Lie of Looking Good 8 4. The Cycle of Loving and Losing 11 PART TWO BODY 5. Existential Anxiety 19 6. From Anxiety to Action 22 7. Get Your Glow On 28 8. When Life Gives You Lyme 32 9. Syphilis and a Second Test 38 10. The Final Clue 44 11. The Self-Care Scandal 54 12. A Self-Care Solution 61 13. What I Learned From Lyme 67 14. Manifestation and Partial Hospitalization 70 15. The Awakening 79 PART THREE BEAUTY 16. Ugly Marks 87 17. A Whole Glow New World 93 18. The Kim Kardashian of Self-Help 105 19. -

A Short Account of the Hartford Convention, Taken from Official

L r. .; ' =====================.......,..J~ -· I \ J / ,- I ; ·.,,, / . .,., ,..: - .l'i . / A .../ \- \ SHORT ACCOUNT Oli' THE TAKEN FRO)I OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS, Al!ID ADDRESSED TO THE FAIR l\1INDED AND THE WELL DISPOSED. TO WHICH IS .iDDED - AN ATTESTED COPY OF TIIB SECRET JOURNAL OF THAT BODY. = EOSTON: PUBLISHED BY O. EVERETT, 13, CORNHILL. 1823. ACCOUNT OF THE Ma. Ons was a member of the Hartford Convention. This is the text, paraphrase and commentary, in all its forms and readings, of all the reproaches, imputations, mis itatements, and misrepresentations, now proclaimed a!ld promulgated against the federal candida.te for Govern or, An objection of the same sort was circulated with even greater vehemence and_ virulence against Governor Brooks, Though .not a member, he was said, in the lan guage of a well-known democratic* paper; to have been the "idol of that body," and to have been designated by them as the leader of the "rebel army," that was to have executed itstreasonable plans. And it is obvious that the same objection would also be uttered against any other candidate, who was a member of the Legislature, which • )Ye do not me this word in any other sense than that of designat-.. ing one of the great political parties of this country. \Ve make this explanation because it is not the purpose of this " Short Account," to cast hasty and indiscriminate reproaches upon the great body of any party. Our simple and single purpose is to present to the people of this State a brief history and vindication of the proceedings of one party upon a most momentous occasion. -

Title Artist Aint No Sunshine Bill Withers Alive Pearl Jam All of Me

Title Artist Aint No Sunshine Bill Withers Alive Pearl Jam All of Me John Stephens / Tobias Gad Always Remember Us This Way Lady Gaga Better Be Home Soon Crowded House Better Man Pearl Jam Blackbird Paul McCartney Blame It On The Boogie Jackson Five Bloodstone Guy Sebastian Blue Moon Elvis Presley Brother Matt Corby Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Budapest George Ezra Chains Tina Arena Change The World Eric Clapton Close to You Hal David/Burt Bacharach Cry In Shame Diesel Dancin In The Street Martha & The Vandellas Dancing In The Dark Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the Moonlight Toploader Dancing Queen ABBA Danny Boy Traditional Days go by Keith Urban December 63 (Oh What a Night) BOB GAUDIO / JUDY PARKER December, 1963 Don't Dream It's Over Crowded House Down Under Men at Work Title Artist Every Breath You take Artist Name Eye of the Tiger Survivor Eyes Forward Shawn MacDonald Fall At Your Feet Crowded House Fast Car Tracy Chapman Father and Son Cat Stevens Fix You Coldplay Fly Me To The Moon chords Frank Sinatra Free fallin Tom Petty The Gambler Kenny Rogers Give you blue Gravity John Mayer Hallelujah Leonard Cohen Hey Jude The Beatles Hey, Soul Sister Train Holy Grail Mark Seymour The Horses Daryl Braithwaite Hotel California Eagles Hound Dog Elvis Presley I Can See Clearly Now Ray Charles I Don't Trust Myself (With Loving You) John Mayer I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For U2 I Wanna Dance With Somebody Whitney Houston I Want to Break Free Queen I'm Gonna Be (500 Miles) The Proclaimers I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Bob Dylan Title Artist In the Summertime Thirsty Merc Isnt She Lovely Stevie Wonder It's a long way to the top ACDC It's Only Natural Crowded House Jekyll & Hyde Jimmy Needham The Joker Steve Miller Band Khe Sanh Cold Chisel Kung Fu Fighting Carl Douglas L.O.V.E.