Negotiating Musicianship Live Weider Ellefsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Film

8/16/2019 LIAM LUNNISS | TELEVISION X Factor Finale w/ James Arthur & Anne Marie Choreographer ITV The Grind 2018 Choreographer MTV The Grind 2017 Choreographer MTV Little Big Shots UK Creative Director/Choreographer ITV/Seasons 1 & 2 Britain's Got Talent "Crying in the Club" w/ Camila Cabello Choreographer ITV The Voice UK "Baby" w/ Pixie Lott Creative Director/Choreographer ITV "Ego" & "Good Times" w/ Ella Eyre Choreographer MTV Britain's Got More Talent w/ Pixie Lott Choreographer ITV The Voice UK "Stitches" w/ Shawn Mendes Choreographer ITV The Voice of Italy Creative Associate/Choreographer RAI/ Season 5 The Voice UK Choreographer ITV/2016 FILM Bohemian Rhapsody Choreographer 20th Century Fox https://msaagency.com/portfolio/liam-lunniss/ 1/4 8/16/2019 LIAM LUNNISS | CONCERTS/TOURS/EVENTS Jingle Bell Ball Tour 2018 w/ Louisa Johnson Choreographer Capital FM Men of the Year Awards "Boys" w/ Charlie XCX Choreographer GQ Rock City Choreographer Celebrity Cruises AWARD SHOWS EMA Awards 2018 Creative Associate MTV EMA Awards 2017 Choreographer MTV EMA Awards 2016 Choreographer MTV EMA "Learn to Let Go" w/ Kesha Choreographer MTV EMA "Break the Rules" w/ Charlie XCX Choreographer MTV EMA "Bailando" w/ Enrique Iglesias Associate Choreographer MTV The Brit Awards w/ Dua Lipa 2018 Associate Choreographer ITV The Brit Awards w/ Katy Perry Associate Choreographer ITV MUSIC VIDEOS Kings of Leon " Waste a Moment" Choreographer https://msaagency.com/portfolio/liam-lunniss/ 2/4 8/16/2019 LIAM LUNNISS | Emi McDade "Faith" Choreographer COMMERCIALS -

Multicam Post-Production Behind the Voice UK

CASE STUDY: Broadcast - The Voice Multicam Post-Production behind The Voice UK For Wall to Wall, the producers of BBC One’s The Voice UK, Envy Post Production used Blackbird to create a workflow for logging from a large-scale multicam setup. CHALLENGE Wall to Wall needed to work with a 17-camera multicam setup with 8 audio tracks from each HD camera source. Standard Avid workflow only supported up to 9 cameras. Using low-budget computers with Core i3 processors, their logging team needed to remotely log all camera feeds simultaneously, with the option for rough cutting. “Having easy access to each artist’s “With so much footage to organise, timelines, including notes, greatly helped The Voice UK vastly benefited particularly the first few weeks of edit.” from Blackbird’s accessibility and flexibility.” Jai Cave Helena Ely Head of Operations, Envy Post Production Head of Production, Wall to Wall SOLUTION Compatibility with the Avid workflow: Allowed the Wall to Wall BENEFITS crew to send MXF camera proxies to a watch folder in the Avid Powered by proxies storage. There the Blackbird Edge Server at Envy’s studios ingested Blackbird’s codec enables them into the Blackbird system. playback of proxy media on low Blackbird’s interface played all 17 camera feeds: Synced cost, low bandwidth connections. together in individual play windows. Remote access in the cloud Easy logging platform: With play windows that allowed loggers to start, stop and log each video with customisable keyboard Video files could instantly shortcuts. be accessed and managed in Blackbird from anywhere in the Producers could easily search: Through logged timelines in world on a standard internet previous footage to create structured edits of each artist’s journey connection. -

Tenby-Arts-Music-2016

Tenby Arts Festval 24t Septmber - 1st Octber 2016 Welcome to all you music lovers. Here is some information about the annual Tenby Arts Festival with an emphasis on the musical events. This year we are particularly proud to be able to present a concert given by the BBC Young Musician of the Year 2016 as well as many other brilliant evenings of music. the opening of the festival will be marked by a Brass Ensemble playing in Tudor Square at 11am. 24th September Cantmus The Messiah ! ! " Under the baton of Welsh National Opera conductor, Alexander Martin, singers from all over Pembrokeshire and beyond, choir members or not will rehearse and perform Handel’s Messiah in the beautiful surroundings of St Mary's Church. He became Chorus Master at WNO at the start of this season. The choir will be accompanied by Jeff Howard, organist. For the past 18 years, Jeffrey has held a post as vocal coach at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama and at Welsh National Opera and Welsh National Youth Opera. For those wishing to join the choir there will be rehearsal before the performance during the day. There will be a charge of £7 for those taking part and in addition a refundable deposit for copies of the music/text. St. Mary’s Church Rehearsals will be at 3pm - 5.30pm Performance 6.30pm - 8pm Tickets £8 Jack Harris Jack Harris writes literate, compassionate songs, about subjects as disparate as Caribbean drinking festivals, the colour of a potato flower and the lives of great poets like Sylvia Plath and Elizabeth Bishop.These have won him considerable acclaim. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Wednesday Volume 654 13 February 2019 No. 252 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 13 February 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 865 13 FEBRUARY 2019 866 Tim Loughton (East Worthing and Shoreham) (Con): House of Commons May I declare an interest, having recently joined the hon. Member for Stretford and Urmston (Kate Green) Wednesday 13 February 2019 on a visit with Oxfam in Jordan? I very much welcome the London initiative. Will urgent steps be taken to take account of the fact that youth unemployment in the The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock country is now some 38%? Not only is there a high level of female unemployment, but the participation rate of women in the workforce in Jordan is even lower than PRAYERS that in Saudi Arabia. Will those urgent objectives be at the heart of what the Secretary of State is trying to achieve? [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Penny Mordaunt: I can reassure my hon. Friend that that will absolutely be the case. This issue has been a Oral Answers to Questions focus for me personally on my visits to Jordan, and I will be focusing on it at the London conference. Mr Barry Sheerman (Huddersfield) (Lab/Co-op): Does INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT the Secretary of State realise that one thing holding back development in Jordan is the number of children and young people killed on the roads there? I spoke at a The Secretary of State was asked— conference in Jordan recently, where we looked at this area. -

2020 Internship Reflection Book

i CONTENTS 1 ABOUT THE REFLECTION ESSAYS Butzin Internship Fund 19 Spending a Summer in Gratitude for Service Dogs 12 Legal Internship 2 A LOOK AT OUR INTERNSHIP FUNDS Sophia Myers ’21 Doing Investigative Work Nick Pomper ’21 20 A Summer of Archival Work 7 REFLECTION ESSAYS in Northfield and Rice County (listed alphabetically by fund, then student) Center for Community and Hannah Zhukovsky ’21 Civic Engagement (CCCE) Abeona Endowed Fund Fellowships Chang-Lan Endowed Fund for International Internships 13 An Internship at the YMCA 21 Researching Protein Engineering 8 Learning about the Film Industries Reveals the Importance in a Lab and Overcoming of France and the United States of Social Connections Research Challenges Alison Hong ’22 Carly Bell ’21 Yiqiu Zhang ’22 9 Autism Research 14 Understanding Disparate in a Virtual Internship Food Access in Rice County Sara Liu ’22 Emily Hall ’21 PICTURED ON COVER American Studies Grant 16 Serving Up much more than Top row: AARON FORMAN ’21, Food in a Community Food Shelf HODAN MOHAMED ’22, 10 Seeing Behind the Curtain MAYA ROGERS ’22, Jack Johnson ’21 of a Political Campaign Office ASTRID PETROPOULOS ’23 Rebecca McCartney ’21 17 The Kaleidoscopic of Richness and Second row: KRISTIN MIYAGI ’22, Diversity of Life in Rice County NARIAH SIMS ’21, MADI SMITH ’22, 11 Supporting Tribal Alexander Kucich ’21 MAX VALE ’22 Sovereignty and Boosting Indigenous Rights 18 Interning at a Food Shelf, Third row: SUAD MOHAMED ’23, TREVOR HUGHES ’21, Thomas White ’22 and Confirming an Interest ANWESHA MUKHERJI ’23, -

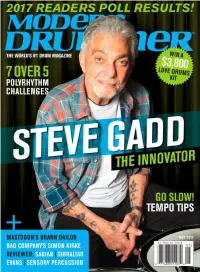

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Trust and Self-Trust in Leadership Identity Constructions: a Qualitative Exploration of Narrative Ecology in the Discursive Aftermath of Heroic Discourse

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Lundberg, Maria Doctoral Thesis Trust and self-trust in leadership identity constructions: A qualitative exploration of narrative ecology in the discursive aftermath of heroic discourse PhD Series, No. 20.2019 Provided in Cooperation with: Copenhagen Business School (CBS) Suggested Citation: Lundberg, Maria (2019) : Trust and self-trust in leadership identity constructions: A qualitative exploration of narrative ecology in the discursive aftermath of heroic discourse, PhD Series, No. 20.2019, ISBN 978-87-93744-83-7, Copenhagen Business School (CBS), Frederiksberg, http://hdl.handle.net/10398/9736 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/222894 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

VAN JA 2021.Indd

Lismore Castle Arts ALICIA REYES MCNAMARA Curated by Berlin Opticians LIGHT AND LANGUAGE Nancy Holt with A.K. Burns, Matthew Day Jackson, Dennis McNulty, Charlotte Moth and Katie Paterson. Curated by Lisa Le Feuvre 28 MARCH - 10 JULY - 10 OCTOBER 2021 22 AUGUST 2021 LISMORE CASTLE ARTS, LISMORE CASTLE ARTS: ST CARTHAGE HALL LISMORE CASTLE, LISMORE, CHAPEL ST, LISMORE, CO WATERFORD, IRELAND CO WATERFORD, IRELAND WWW.LISMORECASTLEARTS.IE +353 (0)58 54061WWW.LISMORECASTLEARTS.IE Image: Alicia Reyes McNamara, She who comes undone, 2019, Oil on canvas, 110 x 150 cm. Courtesy McNamara, She who comes undone, 2019, Oil on canvas, of the artist Image: Alicia Reyes and Berlin Opticians Gallery. Nancy Holt, Concrete Poem (1968) Ink jet print on rag paper taken from original 126 format23 transparency x 23 in. (58.4 x 58.4 cm.). 1 of 5 plus AP © Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. VAN The Visual Artists’ Issue 4: BELFAST PHOTO FESTIVAL PHOTO BELFAST FILM SOCIETY EXPERIMENTAL COLLECTION THE NATIONAL COLLECTIVE ARRAY Inside This Issue July – August 2021 – August July News Sheet News A Visual Artists Ireland Publication Ireland A Visual Artists Contents Editorial On The Cover WELCOME to the July – August 2021 Issue of within the Irish visual arts community is The Visual Artists’ News Sheet. outlined in Susan Campbell’s report on the Array Collective, Pride, 2019; photograph by Laura O’Connor, courtesy To mark the much-anticipated reopening million-euro acquisition fund, through which Array and Tate Press Offi ce. of galleries, museums and art centres, we 422 artworks by 70 artists have been add- have compiled a Summer Gallery Guide to ed to the National Collection at IMMA and First Pages inform audiences about forthcoming exhi- Crawford Art Gallery. -

Oldcastle & Moylagh Parish

Oldcastle & Moylagh Parish 32nd Sunday of the Year Fr Ray Kelly P.P 5th/6th November 2016 049 8541142 The Diocese of Meath is now available on line www.dioceseofmeath.ie Parish Website oldcastleandmoylaghparish.com Church Services & Mass Intentions Masses OLDCASTLE Saturday (vigil) 7.00pm Decd Clinton & Cooney families, Peter Gilsenan Liss, his grandparents Thomas & Mary Francis Griffin & decd family Sunday 11.30am Barney & Rose Farrell Farnaglough, Sheila Savage Kenny Millbrook & decd family members Monday Tuesday 10.00am Wednesday 7.00pm Memorial Mass Declan McMahon Stoney Rd Thursday 10.00am Friday 7.00pm Decd Smith family Summerbank & Fitzsimons family Glenidan Saturday (vigil) 7.00pm 1st Anniv Maureen Lynch Whitehills also Anniv for Annie Lynch St Brigid’s Tce Sunday 11.30am 1st Anniv Liam McNamara Whitehills also rem his wife Mary, Cait & Oliver Beggan Church St, John, Julia & Mary Browne & decd Tobin family MOYLAGH Saturday (vigil) 5.45pm 1st Anniv Margaret Husband, Anniv Mary & Joe McCormack Gortloney Sunday 10.00am Rose Gibney Moylagh, John Monaghan Ballintogher Saturday (vigil) 5.45pm M/M Kathleen Kibble, Anniv Danny Sheridan Baltrasna, Chrissie, Bobby & Sharon Segarty Sunday st 10.00am 1 Anniv James Connell Grennan Monday/Thursday Eucharistic 9.20am/ In Oldcastle 9.00pm Adoration Tuesday 1pm/ 2pm In Moylagh Confessions On request in both Churches Please note e-mail address [email protected] can be used for notices for Mass Bulletin Visit our new Parish Website at www.oldcastleandmoylaghparish.com Altar Servers for Oldcastle Church W/End 5th/6th Nov Groups 2 & 3 – W/End 12th/13th Nov Groups 4 & 5. Readers for November 2016 at St Brigid’s Church, Oldcastle. -

FESTIVAL INFO 2019 Photo: Rob Humm Photo: VILLAGE GREEN STAGE Our Beautiful Saddlespan Stage Is Back!

FESTIVAL INFO 2019 Photo: Rob Humm VILLAGE GREEN STAGE Our beautiful Saddlespan Stage is back! 11:20-11:50 14:40-15:10 18:20-19:20 THE BIG SING BECKIE MARGARET FUN LOVIN’ CRIMINALS This massive choir have performed “Beckie Margaret combines the mystic Led by Huey Morgan, Fun Lovin’ Criminals are alongside Ellie Goulding, London Community beauty of Kate Bush with Dusty Springfield’s still the finest and only purveyors of Gospel Choir, Jamie Oliver & Leona Lewis. sombre reflections” - The Line Of Best Fit cinematic hip-hop, rock ’n’ roll, blues-jazz, Winners of BBC Songs of Praise Gospel Latino soul vibes. Choir of the Year Competition in 2017. 15:30-16:10 ASYLUMS 20:00-21:00 12:10-12:40 “What Southend quartet Asylums have BUSTED KILLATRIX delivered with ‘Alien Human Emotions’ is a Formed in Southend-on-Sea in 2000, Busted A unique hybrid of party-rock-electronica. soundtrack to the modern age.” - Kerrang! have had four UK number-one singles, won As selected to play by the Village Green KKKK two Brit awards and have released four studio Industry panel . albums, selling in excess of five million records. 16:50-17:40 Metal are hugely excited to have secured 13:00-13:30 SNOWBOY Busted to close the popular Village Green Stage KATY FOR KINGS & THE LATIN SECTION as the sun goes down on the festival! “Luck struck” Back by popular demand! - Europe’s leading Katy For Kings is making waves at 18, and is Afro-Cuban Jazz group. From their debut MIDDLE AGE SPREAD showing no signs of slowing down. -

Beautiful Family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble

SARAH BOCKEL (Carole King) is thrilled to be back on the road with her Beautiful family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble. Regional: Million Dollar Quartet (Chicago); u/s Dyanne. Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre- Les Mis; Madame Thenardier. Shrek; Dragon. Select Chicago credits: Bohemian Theatre Ensemble; Parade, Lucille (Non-eq Jeff nomination) The Hypocrites; Into the Woods, Cinderella/ Rapunzel. Haven Theatre; The Wedding Singer, Holly. Paramount Theatre; Fiddler on the Roof, ensemble. Illinois Wesleyan University SoTA Alum. Proudly represented by Stewart Talent Chicago. Many thanks to the Beautiful creative team and her superhero agents Jim and Sam. As always, for Mom and Dad. ANDREW BREWER (Gerry Goffin) Broadway/Tour: Beautiful (Swing/Ensemble u/s Gerry/Don) Off-Broadway: Sex Tips for Straight Women from a Gay Man, Cougar the Musical, Nymph Errant. Love to my amazing family, The Mine, the entire Beautiful team! SARAH GOEKE (Cynthia Weil) is elated to be joining the touring cast of Beautiful - The Carole King Musical. Originally from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, she has a BM in vocal performance from the UMKC Conservatory and an MFA in Acting from Michigan State University. Favorite roles include, Sally in Cabaret, Judy/Ginger in Ruthless! the Musical, and Svetlana in Chess. Special thanks to her vital and inspiring family, friends, and soon-to-be husband who make her life Beautiful. www.sarahgoeke.com JACOB HEIMER (Barry Mann) Theater: Soul Doctor (Off Broadway), Milk and Honey (York/MUFTI), Twelfth Night (Elm Shakespeare), Seminar (W.H.A.T.), Paloma (Kitchen Theatre), Next to Normal (Music Theatre CT), and a reading of THE VISITOR (Daniel Sullivan/The Public). -

Download Brochure

Designed exclusively for adults Breaks from £199* per person Britain’s getting booked Forget the travel quarantines and the Brexit rules. More than any other year, 2021 is the one to keep it local and enjoy travelling through the nation instead of over and beyond it. But why browse hundreds of holiday options when you can cut straight to the Warner 14? Full refunds and free changes on all bookings in 2021 Warner’s Coronavirus Guarantee is free on every break in 2021. It gives the flexibility to cancel and receive a full refund, swap dates or change hotels if anything coronavirus-related upsets travel plans. That means holiday protection against illness, tier restrictions, isolation, hotel closure, or simply if you’re feeling unsure. 2 After the quiet, the chorus is becoming louder. Across our private estates, bands are tuning up, chefs are pioneering new menus and the shows are dress rehearsed. And there’ll be no denying the decadence of dressing up for dinner and cocktails at any o’clock. This is the Twenties after all. And like the 1920s after the Spanish flu, it’ll feel so freeing to come back to wonderful views, delicious food and the best live music and acts in the country, all under the one roof. Who’s ready to get things roaring? A very British story Warner has been offering holidays for almost 90 years with historic mansions and coastal boltholes handpicked for their peaceful grounds and settings. A trusted brand with a signature warm-hearted welcome, we’re once more ready to get back to our roots and celebrate the very best of the land.