8.16 PRABHĀCANDRA, Prameyakamalamārtaṇḍa On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banārasīdās Dans L'histoire De La Pensée

De la convention à la conviction : Banārasīdās dans l’histoire de la pensée digambara sur l’absolu Jérôme Petit To cite this version: Jérôme Petit. De la convention à la conviction : Banārasīdās dans l’histoire de la pensée digambara sur l’absolu. Religions. Université Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2013. Français. tel-01112799 HAL Id: tel-01112799 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01112799 Submitted on 3 Feb 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE SORBONNE NOUVELLE - PARIS 3 ED 268 Langage et langues : description, théorisation, transmission UMR 7528 Mondes iranien et indien Thèse de doctorat Langues, civilisations et sociétés orientales (études indiennes) Jérôme PETIT DE LA CONVENTION À LA CONVICTION BAN ĀRAS ĪDĀS DANS L’HISTOIRE DE LA PENSÉE DIGAMBARA SUR L’ABSOLU Thèse dirigée par Nalini BALBIR Soutenue le 20 juin 2013 JURY : M. François CHENET, professeur, Université Paris-Sorbonne M. John CORT, professeur, Denison University, États-Unis M. Nicolas DEJENNE, maître de conférences, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle Mme. Françoise DELVOYE, directeur d’études, EPHE, Section des Sciences historiques et philologiques Résumé L’œuvre de Ban āras īdās (1586-1643), marchand et poète jaina actif dans la région d’Agra, s’appuie e sur la pensée du maître digambara Kundakunda (c. -

Ratnakarandaka-F-With Cover

Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni VIJAY K. JAIN Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Depiction of the Holy Feet of the twenty-fourth Tīrthaôkara, Lord Mahāvīra, at the sacred hills of Shri Sammed Shikharji, the holiest of Jaina pilgrimages, situated in Jharkhand, India. Pic by Vijay K. Jain (2016) Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct Vijay K. Jain Non-Copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original and that a mention is made of the source. ISBN 81-903639-9-9 Rs. 500/- Published, in the year 2016, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India www.vikalpprinters.com E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun (iv) eaxy vk'khokZn & ijeiwT; fl¼kUrpØorhZ 'osrfiPNkpk;Z Jh fo|kuUn th eqfujkt milxsZ nq£Hk{ks tjfl #tk;ka p fu%izfrdkjs A /ekZ; ruqfoekspuekgq% lYys[kukek;kZ% AA 122 AA & vkpk;Z leUrHkæ] jRudj.MdJkodkpkj vFkZ & tc dksbZ fu"izfrdkj milxZ] -

Buddhist, Jaina, Gandhian & Peace Studies

JK SET Exam P r e v i o u s P a p e r SET 2013 PAPER – III BUDDHIST, JAINA, GANDHIAN AND PEACE STUDIES Signature of the Invigilator Question Booklet No. .................................... 1. OMR Sheet No.. .................................... Subject Code 08 ROLL No. Time Allowed : 150 Minutes Max. Marks : 150 No. of pages in this Booklet : 12 No. of Questions : 75 INSTRUCTIONS FOR CANDIDATES 1. Write your Roll No. and the OMR Sheet No. in the spaces provided on top of this page. 2. Fill in the necessary information in the spaces provided on the OMR response sheet. 3. This booklet consists of seventy five (75) compulsory questions each carrying 2 marks. 4. Examine the question booklet carefully and tally the number of pages/questions in the booklet with the information printed above. Do not accept a damaged or open booklet. Damaged or faulty booklet may be got replaced within the first 5 minutes. Afterwards, neither the Question Booklet will be replaced nor any extra time given. 5. Each Question has four alternative responses marked (A), (B), (C) and (D) in the OMR sheet. You have to completely darken the circle indicating the most appropriate response against each item as in the illustration. AB D 6. All entries in the OMR response sheet are to be recorded in the original copy only. 7. Use only Blue/Black Ball point pen. 8. Rough Work is to be done on the blank pages provided at the end of this booklet. 9. If you write your Name, Roll Number, Phone Number or put any mark on any part of the OMR Sheet, except in the spaces allotted for the relevant entries, which may disclose your identity, or use abusive language or employ any other unfair means, you will render yourself liable to disqualification. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Jainolgy-2020-Final02.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF MYSORE. D.O.S. IN JAINOLOGY & PRAKRITS, Manasagangothri, Mysore-06 S Y L L A B U S - I Semester. HC-1 Paper I (Code:………. ): Doctrines of Jainism-I . Prescribed Text: Tattvarthasutra: Chap - I, II, III, IV & V. 1. Chap. Right Faith and Knowledge, Ratnatraya- MokshaMarga, Pramana & Naya. 2. Chap. Jiva: Classification - Characteristcs – Tiryacs: Sthavara & Trasha . 3. Chap. The Jain Geography- The Lower and the Middle-World, - Infernals - Devas – Human beings – their Births & their Characteristics 4. Chap. Celestial & Other Devas: Classification. 5. Chap. The 6 Dravyas: Jiva, Dharma, Adharma, Akasha, Pudgala & Kala. 6. Chap. Author - Acharya Umaswamy, Important commentaries and commentators. HC-2 Paper II (Code:……. ).: Jaina Ethics- I ---SHRAVAKACARA 1. Chap. Introduction to Jaina Acara, Shravakacara works in Prakrit, Sanskrit & others. 2. Chap. Shravakacara- Minor Vows- Gunavratas and Sikshavratas – Their Aticaras. 3. Chap. Eleven Pratimas of The Shravaka. 4. Chap. Six Essentials –Shatkarmas/Sadhavashyakas. 5. Chap. Sallekhana for the Leity, Justification: Sallekhana is not Sucide. HC-3 Paper III (Code:………. ) Elements of Prakrit Grammar 1. Chap. Alphabets – Vowels and Consonants, peculiarities, Sandhi:Formation & Vicchedha- Vowel Changes: Lengthening Shortening & Other Important Changes. Consonants: Initial – Medial – Terminal Consonantal Changes. Some Special Linguistic Based Changes. 2. Chap. Conjunct Consonants, Prakrit Peculiarities: Similar & Dis-similar – Initial & Medial changes: Assimilation or Samarupakarana, Anaptyxis or Svara-Bhakti, Nasalisation or Anunasikikarna, Lenghtening or Dheerghikarna, other linguistic based Changes. 2 3. Chap. Nouns & Pronouns: their Declension, Verbs (Tense, Person, Number- Gerunds)Pesent tense Forms, Indeclinable, 4. Chap. Simple Prakrit Translation & Composition. 5. Perview of Prakrit by Dr. Padmashekar, published by Samvahana Prakasahana Mysore References : INTRODUCTION TO ARDHAMAGADHI by Prof. -

Vkpk;Z Dqundqun Fojfpr Iapkflrdk;&Laxzg & Izkekf.Kd Vaxzsth O;K[;K Lfgr

Ācārya Kundakunda’s Paôcāstikāya-saÉgraha – With Authentic Explanatory Notes in English (The Jaina Metaphysics) vkpk;Z dqUndqUn fojfpr iapkfLrdk;&laxzg & izkekf.kd vaxzsth O;k[;k lfgr Ācārya Kundakunda’s Paôcāstikāya-saÉgraha – With Authentic Explanatory Notes in English (The Jaina Metaphysics) vkpk;Z dqUndqUn fojfpr iapkfLrdk;&laxzg & izkekf.kd vaxzsth O;k[;k lfgr Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Viśuddhasāgara Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Depiction of the Holy Feet of the twenty-third Tīrthaôkara, Lord Pārśvanātha at the ‘Svarõabhadra-kūÇa’, atop the sacred hills of Shri Sammed Shikharji, Jharkhand, India. Pic by Vijay K. Jain (2016) Ācārya Kundakunda’s Paôcāstikāya-saÉgraha – With Authentic Explanatory Notes in English (The Jaina Metaphysics) Vijay K. Jain Non-copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original. ISBN: 978-81-932726-5-7 Rs. 750/- Published, in the year 2020, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971, Mob.: 9412057845, 9760068668 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun D I V I N E B L E S S I N G S eaxy vk'khokZn & ije iwT; fnxEcjkpk;Z 108 Jh fo'kq¼lkxj th eqfujkt oLrq ds oLrqRo dk HkwrkFkZ cks/ izek.k ,oa u; ds ekè;e ls gh gksrk gS_ izek.k ,oa u; ds vf/xe fcuk oLrq ds oLrqRo dk lR;kFkZ Kku gksuk vlaHko gS] blhfy, Kkuhtu loZizFke izek.k o u; dk xEHkhj vf/xe djrs gSaA u;&izek.k ds lehphu Kku dks izkIr gksrs gh lk/q&iq#"k -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2009 Issue 4 CoJS Newsletter • March 2009 • Issue 4 Centre for Jaina Studies' Members _____________________________________________________________________ SOAS MEMBERS EXTERNAL MEMBERS Honorary President Paul Dundas Professor J Clifford Wright (University of Edinburgh) Vedic, Classical Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit language and literature; comparative philology Dr William Johnson (University of Cardiff) Chair/Director of the Centre Jainism; Indian religion; Sanskrit Indian Dr Peter Flügel Epic; Classical Indian religions; Sanskrit drama. Jainism; Religion and society in South Asia; Anthropology of religion; Religion ASSOCIATE MEMBERS and law; South Asian diaspora. John Guy Professor Lawrence A. Babb (Metropolitan Mueum of Art) Dr Daud Ali (Amherst College) History of medieval South India; Chola Professor Phyllis Granoff courtly culture in early medieval India Professor Nalini Balbir (Yale University) (Sorbonne Nouvelle) Dr Crispin Branfoot Dr Julia Hegewald Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Architecture, Dr Piotr Balcerowicz (University of Manchester) Sculpture and Painting; Pilgrimage and (University of Warsaw) Sacred Geography, Archaeology and Professor Rishabh Chandra Jain Material Religion; South India Nick Barnard (Muzaffarpur University) (Victoria and Albert Museum) Professor Ian Brown Professor Padmanabh S. Jaini The modern economic and political Professor Satya Ranjan Banerjee (UC Berkeley) history of South East Asia; the economic (University of Kolkata) -

Government of India Ministry of Culture Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No

1 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 97 TO BE ANSWERED ON 25.4.2016 VAISAKHA 5, 1938 (SAKA) NATIONAL HERITAGE STATUS 97. SHRI B.V.NAIK; SHRI ARJUN LAL MEENA; SHRI P. KUMAR: Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government has finalized its proposal for sending its entry for world heritage status long with the criteria to select entry for world heritage site status; (b) if so, the details thereof along with the names of temples, churches, mosques and monuments 2Iected and declared as national heritage in various States of the country, State-wise; (c) whether the Government has ignored Delhi as its official entry to UNESCO and if so, the details thereof and the reasons therefor; (d) whether, some sites selected for UNESCO entry are under repair and renovation; (e) if so, the details thereof and the funds sanctioned by the Government in this regard so far, ate-wise; and (f) the action plan of the Government to attract more tourists to these sites. ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE, CULTURE AND TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) AND MINISTER OF STATE, CIVIL AVIATION (DR. MAHESH SHARMA) (a) Yes madam. Government has finalized and submitted the proposal for “Historic City of Ahmedabad” as the entry in the cultural category of the World Heritage List for calendar year 2016-17. The proposal was submitted under cultural category under criteria II, V and VI (list of criteria in Annexure I) (b) For the proposal submitted related to Historic City of Ahmedabad submitted this year, list of nationally important monuments and those listed by Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation are given in Annexure II. -

The Tensions of Karma and Ahimsa

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-31-2016 The eT nsions of Karma and Ahimsa: Jain Ethics, Capitalism, and Slow Violence Anthony Paz Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC000249 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Other Religion Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Paz, Anthony, "The eT nsions of Karma and Ahimsa: Jain Ethics, Capitalism, and Slow Violence" (2016). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2476. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2476 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE TENSIONS OF KARMA AND AHIMSA: JAIN ETHICS, CAPITALISM, AND SLOW VIOLENCE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Anthony Paz 2016 To: Dean John Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Anthony Paz, and entitled The Tensions of Karma and Ahimsa: Jain Ethics, Capitalism, and Slow Violence, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgement. -

Jinendra Pooja Sangrah English Aatmageet (Dr

Jinendra Pooja Sangrah English Aatmageet (Dr. Hukamchand Bharill, Jaipur) (RECITE NAVKAR MANTRA NINE TIMES HERE.) Visarjan Mai Gyananand Swabhawi Hu Mai Hun Apne Mae Swayampurna Bin jaane waa jaan ke rahi toot jo koy, Tum prasaad te param guru so sab pooran hoy. Parkee Mujhmae Kuch Gandh Nahee Mai Aras Arupee Asparsee Pujan vidhi jaanu nahi, nahi jaanu ahaawan, Aur visarjan hoo nahin, kshamaa karo bhagwaan. Parse Kuchbhee Sambandh Nahee Mai Gyananand Swabhawi Hu Mantra-heen dhan-heen hun, kriya-heen jinadev, Kshamaa karahu raakhahu mujhe dehu charan kee sev. Anyatha Sharanam Naasti, Tvamev Sharanam Mama Mai Rang Raagse Bhinn Bhedh Se Tasmaat Kaarunya Bhaaven, Rax Rax Jineshvaram Bhee Mai Bhinn Niraalaa Hu Mai Hu Akhand Chaitanya Peend Aashika Mantra Neej Rasme Ramnewala Hu Mai Gyananand Swabhawi Hu Mangalam Bhagwan Veero, Mangalam Gautamo Gani Mangalam Kundkundaryo, Jain Dharmotsu Mangalam Sarva Mangalya Mangalam, Sarva Kalyan Karanam Mai Hee Meraa Karta Dharta Pradhanam Sarva Dharmanam, Jainam Jayati Shashanam Mujhme Parka Kuch Kaam Nahee (Recite when taking blessings from the sthapanaji) Mai Mujhme Rahnewaalaa Hu Parme Meraa Vishraam Nahee Shree jinver ki aashikaa lijay sheesh namaai, bhav bhav kay paatak haray dukh doora hojai. Mai Gyananand Swabhawi Hu Mai Shudhbudh Avirudhdh Ak Par Pariniti se Aprabhavi Hu Aatnmaanubhuti se Praapt-tatva Mai Gyananand Swabhawi Hu Kshamapana INDEX Bin Jaane VA Jaan Ke, Rahi Toot Jo Koy Tum Prasad Tae Param Guru, So Sab Puran Hoy Information – Pooja, Prakshal & Aarti ............................................ 2 Poojan Vidhi Jaanu Nahi, Nahi Jaanu Avahaan Abhishek (Prakshal) Path ............................................................. 10 Aur Visarjan Hu Nahi, Kshama Karahu Bhagwan Mantrahin Dhanhin Hun, Kriyahin Jindev Adinaath Poojan ....................................................................... -

Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2015 Issue 10 CoJS Newsletter • March 2015 • Issue 10 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christine Chojnacki Dr Andrea Luithle-Hardenberg (University of Lyon) (University of Tübingen) Chair/Director of the Centre Dr Anne Clavel Professor Adelheid Mette Dr Peter Flügel (Aix en Province) (University of Munich) Dr Crispin Branfoot Professor John E. Cort Gerd Mevissen Department of the History of Art (Denison University) (Berliner Indologische Studien) and Archaeology Dr Eva De Clercq Professor Anne E. Monius Professor Rachel Dwyer (University of Ghent) (Harvard Divinity School) South Asia Department Dr Robert J. Del Bontà Professor Hampa P. Nagarajaiah (Independent Scholar) (University of Bangalore) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Saryu V. Doshi Professor Thomas Oberlies Dr Erica Hunter (Mumbai) (University of Göttingen) Department of the Study of Religions Professor M.A. Dhaky Dr Leslie Orr Dr James Mallinson (Ame rican Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon) (Concordia University, Montreal) South Asia Department Professor Christoph Emmrich Dr Jean-Pierre Osier Professor Werner Menski (University of Toronto) (Paris) School of Law Dr Anna Aurelia Esposito Dr Lisa Nadine Owen Professor Francesca Orsini (University of Würzburg) (University of North Texas) South Asia Department Janet Leigh Foster Professor Olle Qvarnström Dr Ulrich Pagel (SOAS Alumna) (University of Lund) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Lynn Foulston Dr Pratapaditya -

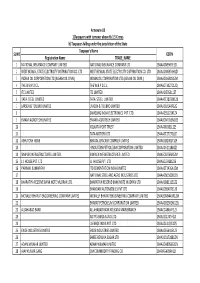

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO.