2007, Volume 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banārasīdās Dans L'histoire De La Pensée

De la convention à la conviction : Banārasīdās dans l’histoire de la pensée digambara sur l’absolu Jérôme Petit To cite this version: Jérôme Petit. De la convention à la conviction : Banārasīdās dans l’histoire de la pensée digambara sur l’absolu. Religions. Université Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2013. Français. tel-01112799 HAL Id: tel-01112799 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01112799 Submitted on 3 Feb 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE SORBONNE NOUVELLE - PARIS 3 ED 268 Langage et langues : description, théorisation, transmission UMR 7528 Mondes iranien et indien Thèse de doctorat Langues, civilisations et sociétés orientales (études indiennes) Jérôme PETIT DE LA CONVENTION À LA CONVICTION BAN ĀRAS ĪDĀS DANS L’HISTOIRE DE LA PENSÉE DIGAMBARA SUR L’ABSOLU Thèse dirigée par Nalini BALBIR Soutenue le 20 juin 2013 JURY : M. François CHENET, professeur, Université Paris-Sorbonne M. John CORT, professeur, Denison University, États-Unis M. Nicolas DEJENNE, maître de conférences, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle Mme. Françoise DELVOYE, directeur d’études, EPHE, Section des Sciences historiques et philologiques Résumé L’œuvre de Ban āras īdās (1586-1643), marchand et poète jaina actif dans la région d’Agra, s’appuie e sur la pensée du maître digambara Kundakunda (c. -

Ratnakarandaka-F-With Cover

Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni VIJAY K. JAIN Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Depiction of the Holy Feet of the twenty-fourth Tīrthaôkara, Lord Mahāvīra, at the sacred hills of Shri Sammed Shikharji, the holiest of Jaina pilgrimages, situated in Jharkhand, India. Pic by Vijay K. Jain (2016) Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct Vijay K. Jain Non-Copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original and that a mention is made of the source. ISBN 81-903639-9-9 Rs. 500/- Published, in the year 2016, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India www.vikalpprinters.com E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun (iv) eaxy vk'khokZn & ijeiwT; fl¼kUrpØorhZ 'osrfiPNkpk;Z Jh fo|kuUn th eqfujkt milxsZ nq£Hk{ks tjfl #tk;ka p fu%izfrdkjs A /ekZ; ruqfoekspuekgq% lYys[kukek;kZ% AA 122 AA & vkpk;Z leUrHkæ] jRudj.MdJkodkpkj vFkZ & tc dksbZ fu"izfrdkj milxZ] -

8.16 PRABHĀCANDRA, Prameyakamalamārtaṇḍa On

This is the original draft of the entry: ‘8.16 PRABHĀCANDRA, Prameyakamalamārtaṇḍa on Māṇikyanandin’s Parīkṣāmukha’ by Piotr Balcerowicz, in: Piotr Balcerowicz and Karl Potter (eds.): Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Vol. XII: Jaina Philosophy, Part II, 2 Vols., Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi [to appear in] 2011. This original version of the synopsis and translation is more philological in character and, in a number of places, it is much more detailed than the printed (abridged) version. It may however contain some mistakes which were eliminated in the printed version. Nevertheless, I hope the reader may still find it useful. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8.16 PRABHĀCANDRA, Prameyakamalamārtaṇḍa on Māṇikyanandin’s Parīkṣāmukha The work (‘The Lotus-like Sun [revealing] Cognisable Objects’), being a commentary on ‘An Introduction to Analysis’, has been edited by Mahendra Kumar Shastri in 1941 (Nirṇaya-sāgara Pres, Muṃbaī), and reprinted in 1990 (Sri Garib Dass Oriental Series, Sri Satguru Publications, Delhi). "E" refers to the pages of that edition. Summary by Piotr Balcerowicz First chapter (on the definition of cognitive criterion) E 1-7. Eulogy in praise of Mahāvīra etc. All objects are well-established due to cognitive criteria (pramāṇa), whereas misconception arises due to fallacy (ābhāsa) of the cognitive criterion. That is one of possible ways to ward off a hypothetical criticism voiced at the outset of the work that PKM is incoherent, illogical and self- contradictory, its subject matter has no real referent; serves no purpose, like a madman’s statement; has not meaningful contents of real subject matter, like an investigation of the crow’s teeth; has no reasonable or realistic purpose, like the discussion of the mother’s remarriage; or it is not possible to accomplish its goal, like a talk of a miraculous gem that cures all afflictions. -

Buddhist, Jaina, Gandhian & Peace Studies

JK SET Exam P r e v i o u s P a p e r SET 2013 PAPER – III BUDDHIST, JAINA, GANDHIAN AND PEACE STUDIES Signature of the Invigilator Question Booklet No. .................................... 1. OMR Sheet No.. .................................... Subject Code 08 ROLL No. Time Allowed : 150 Minutes Max. Marks : 150 No. of pages in this Booklet : 12 No. of Questions : 75 INSTRUCTIONS FOR CANDIDATES 1. Write your Roll No. and the OMR Sheet No. in the spaces provided on top of this page. 2. Fill in the necessary information in the spaces provided on the OMR response sheet. 3. This booklet consists of seventy five (75) compulsory questions each carrying 2 marks. 4. Examine the question booklet carefully and tally the number of pages/questions in the booklet with the information printed above. Do not accept a damaged or open booklet. Damaged or faulty booklet may be got replaced within the first 5 minutes. Afterwards, neither the Question Booklet will be replaced nor any extra time given. 5. Each Question has four alternative responses marked (A), (B), (C) and (D) in the OMR sheet. You have to completely darken the circle indicating the most appropriate response against each item as in the illustration. AB D 6. All entries in the OMR response sheet are to be recorded in the original copy only. 7. Use only Blue/Black Ball point pen. 8. Rough Work is to be done on the blank pages provided at the end of this booklet. 9. If you write your Name, Roll Number, Phone Number or put any mark on any part of the OMR Sheet, except in the spaces allotted for the relevant entries, which may disclose your identity, or use abusive language or employ any other unfair means, you will render yourself liable to disqualification. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Jainolgy-2020-Final02.Pdf

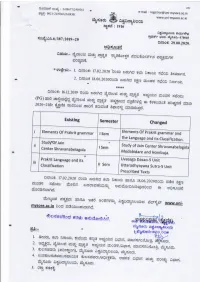

UNIVERSITY OF MYSORE. D.O.S. IN JAINOLOGY & PRAKRITS, Manasagangothri, Mysore-06 S Y L L A B U S - I Semester. HC-1 Paper I (Code:………. ): Doctrines of Jainism-I . Prescribed Text: Tattvarthasutra: Chap - I, II, III, IV & V. 1. Chap. Right Faith and Knowledge, Ratnatraya- MokshaMarga, Pramana & Naya. 2. Chap. Jiva: Classification - Characteristcs – Tiryacs: Sthavara & Trasha . 3. Chap. The Jain Geography- The Lower and the Middle-World, - Infernals - Devas – Human beings – their Births & their Characteristics 4. Chap. Celestial & Other Devas: Classification. 5. Chap. The 6 Dravyas: Jiva, Dharma, Adharma, Akasha, Pudgala & Kala. 6. Chap. Author - Acharya Umaswamy, Important commentaries and commentators. HC-2 Paper II (Code:……. ).: Jaina Ethics- I ---SHRAVAKACARA 1. Chap. Introduction to Jaina Acara, Shravakacara works in Prakrit, Sanskrit & others. 2. Chap. Shravakacara- Minor Vows- Gunavratas and Sikshavratas – Their Aticaras. 3. Chap. Eleven Pratimas of The Shravaka. 4. Chap. Six Essentials –Shatkarmas/Sadhavashyakas. 5. Chap. Sallekhana for the Leity, Justification: Sallekhana is not Sucide. HC-3 Paper III (Code:………. ) Elements of Prakrit Grammar 1. Chap. Alphabets – Vowels and Consonants, peculiarities, Sandhi:Formation & Vicchedha- Vowel Changes: Lengthening Shortening & Other Important Changes. Consonants: Initial – Medial – Terminal Consonantal Changes. Some Special Linguistic Based Changes. 2. Chap. Conjunct Consonants, Prakrit Peculiarities: Similar & Dis-similar – Initial & Medial changes: Assimilation or Samarupakarana, Anaptyxis or Svara-Bhakti, Nasalisation or Anunasikikarna, Lenghtening or Dheerghikarna, other linguistic based Changes. 2 3. Chap. Nouns & Pronouns: their Declension, Verbs (Tense, Person, Number- Gerunds)Pesent tense Forms, Indeclinable, 4. Chap. Simple Prakrit Translation & Composition. 5. Perview of Prakrit by Dr. Padmashekar, published by Samvahana Prakasahana Mysore References : INTRODUCTION TO ARDHAMAGADHI by Prof. -

JAINISM Early History

111111xxx00010.1177/1111111111111111 Copyright © 2012 SAGE Publications. Not for sale, reproduction, or distribution. J Early History JAINISM The origins of the doctrine of the Jinas are obscure. Jainism (Jinism), one of the oldest surviving reli- According to tradition, the religion has no founder. gious traditions of the world, with a focus on It is taught by 24 omniscient prophets, in every asceticism and salvation for the few, was confined half-cycle of the eternal wheel of time. Around the to the Indian subcontinent until the 19th century. fourth century BCE, according to modern research, It now projects itself globally as a solution to the last prophet of our epoch in world his- world problems for all. The main offering to mod- tory, Prince Vardhamāna—known by his epithets ern global society is a refashioned form of the Jain mahāvīra (“great hero”), tīrthaṅkāra (“builder of ethics of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and nonpossession a ford” [across the ocean of suffering]), or jina (aparigraha) promoted by a philosophy of non- (spiritual “victor” [over attachment and karmic one-sidedness (anekāntavāda). bondage])—renounced the world, gained enlight- The recent transformation of Jainism from an enment (kevala-jñāna), and henceforth propagated ideology of world renunciation into an ideology a universal doctrine of individual salvation (mokṣa) for world transformation is not unprecedented. It of the soul (ātman or jīva) from the karmic cycles belongs to the global movement of religious mod- of rebirth and redeath (saṃsāra). In contrast ernism, a 19th-century theological response to the to the dominant sacrificial practices of Vedic ideas of the European Enlightenment, which West- Brahmanism, his method of salvation was based on ernized elites in South Asia embraced under the the practice of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and asceticism influence of colonialism, global industrial capital- (tapas). -

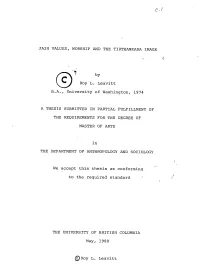

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

Jain Thoughts and Prayers Jain Thoughts and Prayers

JAIN THOUGHTS AND PRAYERS JAIN THOUGHTS AND PRAYERS (The Sacred Picther : Kalash) PROFESSOR KANTI V. MARDIA PROFESSOR KANTI V. MARDIA THE YORKSHIRE JAIN FOUNDATION (YJF) 14 ANCASTER ROAD, WEST PARK THE YORKSHIRE JAIN FOUNDATION LEEDS LS16 5HH, ENGLAND Launched on - 15th April 2007, 20th YJF ANNIVERSARY For Private & Personal Use Only www.yjf.org.uk 2 PROFESSOR KANTI V. MARDIA ISBN 0 9520144 0 8 First Edition : 25th April 1992 Mahavir Jayanti, Launched by Dr. Paul Marett Second Edition : 15th April 2007, 20th YJF Anniversary For Private & Personal Use Only www.yjf.org.uk 3 For Private & Personal Use Only www.yjf.org.uk 4 tSu fopkj vkSj izkFkZuk;ssa Mahaavira Swami, the 24th Tirthankara izksQslj dkafr oh- ejfM;k (Svetambara image from Sirohi, Raj.) ;ksdZ”kk;j tSu QkmaMs”ku- yhM~l] ;w-ds- Leeds, UK. For Private & Personal Use Only www.yjf.org.uk 5 For Private & Personal Use Only www.yjf.org.uk 6 INSPIRING QUOTATIONS “Freedom from destructive emotions in reality is the true enlightenment. "Science without religion is lame, Religion without (Kashaaya Mukti kill Muktirev).” science is blind." Einstein ".... a person who is religiously enlightened appears to me to be one who has, to the best of his ability, liberated himself from the fetters of his selfish desires . ." Einstein (Jain = "Person who has conquered himself/herself.") Kashaaya (Destructive Emotions) =Anger + Greed + Ego + Deceit = 'AGED' = Againg agents. ************ "The Worldly Hope men set their Hearts upon Turn Ashes - or it prospers: and anon, Like Snow upon the Desert's dusty Face Lighting a little Hour or two - is Situation and volitional activities with karmic gone" force lines from Mardia K.V., (2002). -

Vkpk;Z Dqundqun Fojfpr Iapkflrdk;&Laxzg & Izkekf.Kd Vaxzsth O;K[;K Lfgr

Ācārya Kundakunda’s Paôcāstikāya-saÉgraha – With Authentic Explanatory Notes in English (The Jaina Metaphysics) vkpk;Z dqUndqUn fojfpr iapkfLrdk;&laxzg & izkekf.kd vaxzsth O;k[;k lfgr Ācārya Kundakunda’s Paôcāstikāya-saÉgraha – With Authentic Explanatory Notes in English (The Jaina Metaphysics) vkpk;Z dqUndqUn fojfpr iapkfLrdk;&laxzg & izkekf.kd vaxzsth O;k[;k lfgr Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Viśuddhasāgara Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Depiction of the Holy Feet of the twenty-third Tīrthaôkara, Lord Pārśvanātha at the ‘Svarõabhadra-kūÇa’, atop the sacred hills of Shri Sammed Shikharji, Jharkhand, India. Pic by Vijay K. Jain (2016) Ācārya Kundakunda’s Paôcāstikāya-saÉgraha – With Authentic Explanatory Notes in English (The Jaina Metaphysics) Vijay K. Jain Non-copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original. ISBN: 978-81-932726-5-7 Rs. 750/- Published, in the year 2020, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971, Mob.: 9412057845, 9760068668 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun D I V I N E B L E S S I N G S eaxy vk'khokZn & ije iwT; fnxEcjkpk;Z 108 Jh fo'kq¼lkxj th eqfujkt oLrq ds oLrqRo dk HkwrkFkZ cks/ izek.k ,oa u; ds ekè;e ls gh gksrk gS_ izek.k ,oa u; ds vf/xe fcuk oLrq ds oLrqRo dk lR;kFkZ Kku gksuk vlaHko gS] blhfy, Kkuhtu loZizFke izek.k o u; dk xEHkhj vf/xe djrs gSaA u;&izek.k ds lehphu Kku dks izkIr gksrs gh lk/q&iq#"k -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2009 Issue 4 CoJS Newsletter • March 2009 • Issue 4 Centre for Jaina Studies' Members _____________________________________________________________________ SOAS MEMBERS EXTERNAL MEMBERS Honorary President Paul Dundas Professor J Clifford Wright (University of Edinburgh) Vedic, Classical Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit language and literature; comparative philology Dr William Johnson (University of Cardiff) Chair/Director of the Centre Jainism; Indian religion; Sanskrit Indian Dr Peter Flügel Epic; Classical Indian religions; Sanskrit drama. Jainism; Religion and society in South Asia; Anthropology of religion; Religion ASSOCIATE MEMBERS and law; South Asian diaspora. John Guy Professor Lawrence A. Babb (Metropolitan Mueum of Art) Dr Daud Ali (Amherst College) History of medieval South India; Chola Professor Phyllis Granoff courtly culture in early medieval India Professor Nalini Balbir (Yale University) (Sorbonne Nouvelle) Dr Crispin Branfoot Dr Julia Hegewald Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Architecture, Dr Piotr Balcerowicz (University of Manchester) Sculpture and Painting; Pilgrimage and (University of Warsaw) Sacred Geography, Archaeology and Professor Rishabh Chandra Jain Material Religion; South India Nick Barnard (Muzaffarpur University) (Victoria and Albert Museum) Professor Ian Brown Professor Padmanabh S. Jaini The modern economic and political Professor Satya Ranjan Banerjee (UC Berkeley) history of South East Asia; the economic (University of Kolkata) -

The Nonhuman and Its Relationship to The

THE UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA WORLDLY AND OTHER-WORLDLY ETHICS: THE NONHUMAN AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO THE MEANINGFUL WORLD OF JAINS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES © MÉLANIE SAUCIER, OTTAWA, CANADA, 2012 For my Parents And for my Animal Companions CONTENTS Preface i Introduction 1 Definition of Terms and Summary of Chapters: Jain Identity and The Non-Human Lens 2 Methodology 6 Chapter 1 - The Ascetic Ideal: Renouncing A Violent World 10 Loka: A World Brimming with Life 11 Karma, Tattvas, and Animal Bodies 15 The Wet Soul: Non-Human Persons and Jain Karma Theory 15 Soul and the Mechanisms of Illusion 18 Jain Taxonomy: Animal Bodies and Violence 19 Quarantining Life 22 The Flesh of the Plant is Good to Eat: Pure Food for the Pure Soul 27 Jain Almsgiving: Gastro-Politics and the Non-Human Environment 29 Turning the Sacrifice Inwards: The Burning Flame of Tapas 31 Karma-Inducing Diet: Renouncing to Receive 32 Karma-Reducing Diet: Receiving to Renounce 34 Spiritual Compassion and Jain Animal Sanctuaries 38 Chapter 2 – Jainism and Ecology: Taking Jainism into the 21st Century 42 Neo-Orthodox and Eco-Conscious Jains: Redefining Jainism and Ecology 43 The Ascetic Imperative in a “Green” World 45 Sadhvi Shilapi: Treading the Mokşa-Marga in an Environmentally Conscious World 47 Surendra Bothara: Returning to True Form: A Jain Scholar‟s Perspective on the Inherent Ecological Framework of Jainism 51 “Partly Deracinated” Jainism: