World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expolanka Holdings Plc Integrated Annual Report

EXPOLANKA HOLDINGS PLC INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2020/21 EXPOLANKA HOLDINGS PLC | INTEGRATED REPORT 2020/21 2 fruitionEXPOLANKA HOLDINGS PLC | INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2020/21 At Expolanka, we remain fully committed to our promise made several years ago, to drive long term sustainable value, by adapting a focused, constant and consistent strategy. Even though the year under review post several challenges, we were able to pursue our said strategies and bring to fruition our plans for progress which was fueled by our innate resilience and strength. The seeds we planted have taken root and we keep our focus upward, expanding in our focused direction in order to adapt to the current environment. We remain fruitful in our optimism, our can-do attitude and endurance, a recipe for success that will carry us through to more opportunity. Overview EXPOLANKA HOLDINGS PLC | INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2020/21 2 CONTENTS Chairman’s Overview Compliance Reports 12 About Us 3 Corporate Governance 71 Message About this Report 4 Risk Management Report 93 Group Milestones 5 Related Party Transactions Financial Highlights 6 Review Committee Report 101 15 Group CEO’s Highlights of the Year 7 Remuneration Committee Report 103 Review Chairman’s Message 12 Group CEO’s Review 15 Financial Reports Board of Directors 18 Annual Report of the Board of Directors Group Senior Management Team 20 on the Affairs of the Company 108 23 Financial Indicators 22 The Statement of Directors’ Responsibility 112 Performance Group Performance 23 Audit Committee Report 113 Overcoming -

Annual Report 2012/2013

THE PURSUIT OF EXCELLENCE One hundred years of passion, hard work and perseverance have brought to where we are today: a highly respected, fast growing blue chip conglomerate with interests in several key growth industry sectors: beverages, telecommunications, plantations, hotels, textiles, finance, insurance, power genaration, media and logistics. And yet, we will not rest. Our story is far from over. Indeed, it has only just begun. Look to us for even greater achievements as we step into the next century of our lifetime, to build further upon our current successes. DCSL. 100 years in the passionate pursuit of excellence. Distilleries Company of Sri Lanka PLC | Annual Report 2012/13 1 Financial Highlights 2013 2012 2013 2012 Group Group Company Company Summary of Results Gross Turnover Rs Mn 65,790 63,125 51,549 49,136 Excise Duty Rs Mn 37,024 36,150 34,088 33,860 Net Turnover Rs Mn 28,766 26,975 17,461 15,276 Profit After Tax Rs Mn 5,258 6,052 6,873 4,297 Shareholders Funds Rs Mn 47,978 41,576 39,155 32,597 Working Capital Rs Mn (1,298) (3,234) (6,139) (21,374) Total Assets Rs Mn 78,245 73,355 55,942 62,563 Staff Cost Rs Mn 3,194 3,155 1,039 1,080 No. of Employees 18,674 18,158 1,343 1,389 Per Share Basic Earnings* Rs. 17.13 18.45 10.68 11.85 Net Assets Rs. 159.93 138.59 130.52 108.66 Dividends Rs. 3.00 3.00 3.00 3.00 Market Price - High Rs. -

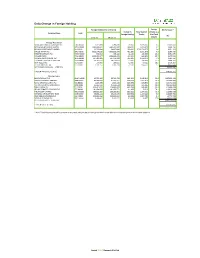

Daily Change in Foreign Holding

Daily Change in Foreign Holding Foreign Holding (No. of Shares) Foreign Net Turnover * Change in Total Volume Volume as a Company Name Code Foreign Holding Traded % of Total Rs. Volume 1-Feb-21 29-Jan-21 Foreign Purchases LANKA ORIX LEASING COMPANY PLC LOLC.N0000 2,313,835 2,286,635 27,200 2,699,110 1.0 13,702,000 EXPOLANKA HOLDINGS LIMITED EXPO.N0000 1,483,800,622 1,483,612,587 188,035 9,893,475 1.9 9,646,196 BROWNS INVESTMENTS LIMITED BIL.N0000 39,790,648 38,857,648 933,000 2,710,774,277 0.0 6,251,100 DIALOG AXIATA PLC DIAL.N0000 7,503,174,020 7,502,692,370 481,650 5,891,576 8.2 6,068,790 SWISSTEK (CEYLON) PLC PARQ.N0000 536,541 495,422 41,119 183,663 22.4 5,951,975 RICHARD PIERIS RICH.N0000 1,535,157,477 1,534,940,476 217,001 643,305 33.7 3,472,016 PIRAMAL GLASS CEYLON PLC GLAS.N0000 567,423,605 567,159,200 264,405 3,624,074 7.3 2,591,169 CHEVRON LUBRICANTS LANKA PLC LLUB.N0000 39,685,643 39,669,043 16,600 108,104 15.4 1,809,400 JOHN KEELLS PLC JKL.N0000 234,960 218,015 16,945 59,322 28.6 1,418,297 CIC HOLDINGS PLC (X) CIC.X0000 3,511,252 3,483,738 27,514 858,562 3.2 1,317,921 NET FOREIGN PURCHASE (TOP TEN) 52,228,863 FOREIGN PURCHASE (TOTAL) 149,626,332 Foreign Sales SAMPATH BANK PLC SAMP.N0000 49,752,499 50,713,780 (961,281) 2,948,613 32.6 (187,690,115) HATTON NATIONAL BANK PLC HNB.N0000 90,479,629 91,019,351 (539,722) 1,012,713 53.3 (81,363,092) ROYAL CERAMICS LANKA PLC RCL.N0000 1,825,896 1,946,188 (120,292) 826,955 14.5 (46,071,836) HATTON NATIONAL BANK PLC (X) HNB.X0000 25,447,044 25,629,644 (182,600) 625,195 29.2 (21,546,800) -

Annual Report 2014

BLENDING WITH THE NATION'S GROWTH Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC Annual Report 2014 CONTENTS Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC Our Vision / 02 Chevron House, 490, Galle Road, Financial Highlights / 03 Colombo, Sri Lanka Status: Listed Chairman’s Review / 06 Legal Form: Public Limited Company Managing Director’s Review of Operations / 08 Financial Auditors: PricewaterhouseCoopers Board of Directors / 12 www.chevron.com Management Team / 14 Management Discussion & Analysis / 18 Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC engages Financial Review / 24 in blending, manufacturing, importing, Corporate Social Responsibility Report / 26 distributing, and marketing lubricants oils, Corporate Governance / 30 greases, brake fluids, and specialty products Risk Management / 35 in Sri Lanka. The Company offers its products for industrial, commercial, and consumer applications. Chevron Lubricants Lanka Financial Calender / 37 PLC markets its products under Chevron, Annual Report of the Directors / 38 Caltex, and Texaco brands. The Company was Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities / 40 incorporated in 1992 and is based in Colombo, Audit Committee Report / 41 Sri Lanka. Remuneration Committee Report / 42 Independent Auditor’s Report / 43 Income Statement / 44 Statement of Comprehensive Income / 45 Chevron Lubricants Statement of Financial Position / 46 Lanka PLC Statement of Changes in Equity / 47 Annual Report 2014 Cash Flow Statement / 48 Notes to the Financial Statements / 49 Statement of Value Added / 73 Ten Year Summary / 74 Shareholder Information / 75 Notice of Annual General Meeting / 77 Form of Proxy / 79 Scan this QR code with your smart device to view this version of the Annual report online www.chevron.lk/reports GROWTHBLENDING WITH THE NATION'S Chevron Lanka has always been a benchmark of business excellence in Sri Lanka, with a strong focus on value creation at every level of our business and production process. -

Annual Report 2016 Www

Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC Annual Report 2016 www. chevron.lk Keeping our Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC Annual Report 2016 1 Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC Annual Report 2016 www. chevron.lk 2 Annual Report 2016 Keeping our FOCUS Chevron Lanka has delivered yet another year of outstanding results. Your company stood strong, engaging with the issues, working on intelligent solutions and increasing our focus on stakeholder value creation. We have always counted on our strong local and global synergies and the unmatched expertise in technology and industry innovation we own. Over the years we have shared this knowledge, continuing our vision to bring a positive impact to the people and communities we serve, while significantly contributing to the economy of Sri Lanka. Contents 4 Our Vision 5 Financial Highlights 6 Chairman’s Review 8 Managing Director’s Review 12 Board of Directors 16 Management Team 18 Management Discussion & Analysis 27 Financial Review 31 Corporate Social Responsibility 33 Corporate Governance 39 Risk Management 42 Financial Calender 43 Annual Report of the Directors 46 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 47 Audit Committee Report 48 Related Party Transactions Review Committee Report 49 Certificate of the Director on Transfer Pricing 50 Remuneration Committee Report 51 Independent Auditor’s Report 52 Income Statement 53 Statement of Comprehensive Income 54 Statement of Financial Position 55 Statement of Changes in Equity 56 Cash Flow Statement 57 Notes to the Financial Statements 84 Ten Year Financial Summary 85 Statement of Value Added 86 Shareholder Information 89 Notice of Annual General Meeting 90 Corporate Information 91 Form of Proxy Annual Report Online www.chevron.lk/reports 2 Our Family of Brands Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC engages in blending, manufacturing, importing, distributing and marketing lubricants oils, greases, brake fluids and specialty products in Sri Lanka. -

The Annual Report on Sri Lanka's Most Valuable and Strongest Brands April

Sri Lanka 100 2018 The annual report on Sri Lanka’s most valuable and strongest brands April 2018 Contents. Foreword - David Haigh 4 Foreword - Ruchi Gunewardene 5 About Brand Finance 6 Consulting Services 7 Definitions 8 Executive Summary 10 Consumer Brands Table 14 Understand Your Brand’s Value 16 Methodology 17 Our Clients 18 Our Services in Sri Lanka 19 Our People 20 Foreword. The Annual Review of Sri Lanka’s Brands. What is the purpose of a strong brand: to attract customers, to build loyalty, to Brand Finance Lanka has been publishing Sri Lanka’s brand league table consisting motivate staff? All true, but for a commercial brand at least, the first answer must of the most valuable brands for 15 consecutive years. Over the years, we have added always be ‘to make money’. and enhanced this so as to provide our readers with a well researched and definitive annual guide to the most valuable and strongest brands that are operating in Sri Huge investments are made in the design, launch, and ongoing promotion of Lanka. brands. Given their potential financial value, this makes sense. Unfortunately, most organisations fail to go beyond that, missing huge opportunities to Doing so requires data for a fact-based analysis and we use two sources. One is the effectively make use of what are often their most important assets. Monitoring of financial data available from listed companies on the Colombo Stock Exchange brand performance should be the next step, but is often sporadic. Where it does (CSE) and the other is the exclusive market research study that is conducted for take place, it frequently lacks financial rigour and is heavily reliant on qualitative Brand Finance Lanka. -

Appendix D: Securities Held by Funds

Annual Report of Activities Pursuant to Act 44 of 2010 September 30, 2015 Appendix D: Securities Held by Funds The Four Funds hold thousands of publicly and privately traded securities. Act 44 directs the Four Funds to publish “a list of all publicly traded securities held by the public fund.” For consistency in presenting the data, a list of all holdings of the Four Funds is obtained from Pennsylvania Treasury Department. The list includes privately held securities. Some privately held securities lacked certain data fields to facilitate removal from the list. To avoid incomplete removal of privately held securities or erroneous removal of publicly traded securities from the list, the Four Funds have chosen to report all publicly and privately traded securities. The list below presents the securities held by the Four Funds as of June 30, 2015. 1011778 BC ULC / NEW RED 144A ABCAM PLC ACCELYA KALE SOLUTIONS LTD 198 INVERNESS DRIVE WEST ABC-MART INC ACCENTURE PLC 21ST CENTURY FOX AMERICA INC ABC-MART INC NPV CFD ACCESS CIG 10/14 TL 21ST CENTURY ONCOLOGY 4/15 TL ABENGOA SA ACCIONA SA 22ND CENTURY GROUP INC ABENGOA YIELD PLC ACCO BRANDS CORP 32 CAPITAL FUND LTD (THE) ABERCROMBIE & FITCH CO ACCOR SA 361 DEGREES INTERNATIONAL LTD ABERDEEN ASSET MANAGEMENT PLC ACCRETIVE CO LTD CFD 3D SYSTEMS CORP ABERTIS INFRAESTRUCTURAS SA ACCRUED INTEREST FOR PRIVATE 3I GROUP PLC ABILITY ENTERPRISE CO LTD ACCTON TECHNOLOGY CORP 3M CO ABILITY NETWORK 5/14 COV-LITE ACCUVANT 12/14 COV-LITE 2ND 4L TECHNOLOGIES 5/14 COV-LITE ABINGWORTH BIOVENTURE V LP ACCUVANT 12/14 -

EPF Department of Central Bank of Sri Lanka Listed Equity Portfolio (Trading) As at 30/09/2018

EPF Department of Central Bank of Sri Lanka Listed Equity Portfolio (Trading) as at 30/09/2018 Rs. 000 Original Purchased No. Company Name No. of Shares Market Value Cost 1 ACL Cables Ltd 407,166 22,978.15 15,146.58 2 ACL Placstics PLC 153,063 19,892.82 12,183.81 3 Access Engineering PLC 4,694,885 102,915.50 65,258.90 4 Aitken Spence Co 3,170,859 280,028.13 136,029.85 5 Aitken Spence Hotels 2,838,466 164,977.10 71,529.34 6 Asian Hotels & Properties PLC 1,907,562 96,297.36 75,539.46 7 Balangoda Plantations 1,351,098 40,338.11 17,699.38 8 Bogawantalawa Tea State PLC 81,724 1,463.19 817.24 9 Browns & Co PLC 249,050 25,399.54 12,452.50 10 Browns Capital PLC 104,900 524.50 356.66 11 Browns Investment PLC_Voting 2,082,858 3,689.83 3,957.43 12 Bukith Darah 3,639 2,613.79 764.19 13 C W Mackie PLC 139,740 12,643.85 6,288.30 14 CIC Holdings PLC - Non Voting 341,335 29,551.80 12,083.26 15 CIC Holdings PLC Voting 1,114,909 119,043.32 52,400.72 16 Cargills (Cey) PLC 16,514 2,274.24 3,301.21 17 Carsons Cumberbatch PLC 30,429 13,160.41 5,172.93 18 Central Finance Company PLC 654,169 74,971.02 59,660.25 19 Ceylon Guardian Investment PLC 229,142 40,107.95 16,039.92 20 Ceylon Hospitals PLC - Voting 1,076,985 106,534.11 80,666.18 21 Ceylon Tea Services PLC 32,225 23,494.57 17,788.20 22 Ceylon Theatres 50,016 6,506.74 9,002.86 23 Chemanex PLC 23,288 1,454.47 1,276.18 24 DIMO PLC 125,282 88,707.20 43,811.12 25 Dialog Telekom 48,068 505.44 572.01 26 Dipped Products 582,865 65,127.94 44,880.61 27 EXPOLANKA HOLDINGS PLC_VOTING 966,450 8,420.58 3,865.80 28 Hayleys -

Annual Report 2019 Report Annual Strength

CHEVRON LUBRICANTS LANKA PLC SYNERGY OF | ANNUAL REPORT 2019 STRENGTH Our family of brands CHEVRON LUBRICANTS LANKA PLC | ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 01 SYNERGY OF STRENGTH taying formidable in a market that is fiercely competitive requires an S unparalleled level of team spirit, partnership and determination. At Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC, the synergy of our strength comes from our people, who have today elevated us to become a pre-eminent marketer of lubricants with a far-reaching presence in Sri Lanka. We are also proud to announce that as a result of the combined efforts of our team, we were able to maintain our impeccable safety record of 18 years since the last lost time from an injury. As we navigated a challenging course, we continued to forge ahead – relying on the efficient management of our operations, and equipping ourselves to achieve continuity and enhanced performance in the long run. We’re taking on the challenges of the future, as a well - oiled machine that function flawlessly. In motorsports, pit stop teams are a pure representation of teamwork, synergy and synchronicity. Each individual contributes towards achieving a single goal - to build endurance and guarantee survival. This report pays tribute to the outstanding performance and winning spirit of the Chevron Lanka team, who ensured we remained competitive despite the challenging conditions we faced during the year. 02 SYNERGY OF STRENGTH ANNUAL REPORT 2019 03 CONTENTS CORPORATE OVERVIEW Financial Highlights 04 06 Vision, Our Values 05 Chairperson’s Review -

The Bourse Concludes Within the Positive Terrain…

Index 06th Aug 05th Aug Change % Change The bourse concludes within the positive terrain… ASPI 6,121.45 6,114.18 7.27 0.12% The Market recovered to some extent from its bear run as S&P SL20 3,477.04 3,471.47 5.57 0.16% Market Statistics 06th Aug 05th Aug the indices reversed the gear, to conclude within the green Value of Turnover(Rs.) 531,860,948 288,422,418 terrain; this was having lost 42 points during the previous Domestic Purchases 168,004,358 174,315,050 trading day. The benchmark ASPI gathered 7.27 points or Domestic Sales 318,363,207 145,061,106 0.12% to conclude at 6,121.45. The S&P SL20 too closed Foreign Purchases 363,856,590 114,107,369 positive gaining 5.57 points or 0.16% to settle the day at Foreign Sales 213,497,741 143,361,313 3,477.04. As at the day’s close, the total market Volume of Turnover (No.) 23,209,194 16,202,478 capitalization stood at LKR 2.36Tn, charting a year to date PER 16.20 16.18 gain of 8.68%. The market PER & PBV stood at 16.20 and 2.18 PBV 2.18 2.17 respectively. The day witnessed an aggregate turnover of 531.86Mn, 7,000 6,037.22 6,156.60 6,155.82 6,114.18 6,121.45 6,000 indicating a rise of 84.40% against its previously recorded; 5,000 nearly 55% of this was accounted by the top three contributors for the day. -

Annual Report 2020 4

ADAPT-ABILITY noun: the quality of being able to adjust to new conditions. In a fast-changing environment, the ability to adapt is a necessity. That’s why at Chevron Lanka, we endeavor to prepare for any eventuality; reliant on decades of experience in a fiercely competitive market. Over time we have continued to fine-tune a structure designed to deliver consistent value, continuous improvement, and robust performance. As we face the unknown, we are gearing ourselves to face the challenges that tomorrow holds. We are shaping and sculpting your company to explore a future of exciting new possibilities; relying on our collective skill, knowledge, and versatility to deploy creative strategies and engineer solutions designed to anticipate change, address the people’s needs, and transform both your future and ours. We are continuing to adapt to a future of change, while ensuring constant progress in the face of adversity. Origami is an old Japanese art form which has, over the years, evolved into a craft that stimulates aspects of strategic thinking, innovation and problem solving. It represents the versatility and adaptability of a single entity — the ability to transform itself into a new structure that is fully functional, durable, and multidimensional. 2 / Contents 04 32 CORPORATE OVERVIEW GOVERNANCE Financial Highlights 04 Corporate Governance 32 Vision, Our Values 05 Risk Management 38 Annual Report of the Directors 41 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 43 Audit Committee Report 44 Related Party Transactions Review Committee Report -

Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC Annual Report 2017 STRENGTH

ICON OF Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC Lanka Lubricants Chevron STRENGTH Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2017 Report Annual Contents 2 Our Vision 3 Financial Highlights 4 Chairperson’s Review 6 Managing Director’s Review 10 Board of Directors 12 Management Team 14 Management Discussion & Analysis 20 Financial Review 24 Corporate Social Responsibility 26 Corporate Governance 32 Risk Management 35 Financial Calender 36 Annual Report of the Directors 39 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 40 Audit Committee Report 41 Related Party Transactions Review Committee Report 43 Certificate of the Director on Transfer Pricing 44 Remuneration Committee Report 45 Independent Auditor’s Report 46 Income Statement 47 Statement of Comprehensive Income 48 Statement of Financial Position 49 Statement of Changes in Equity 50 Cash Flow Statement 51 Notes to the Financial Statements 78 Ten Year Financial Summary 79 Statement of Value Added 80 Shareholder Information 82 Notice of Annual General Meeting 83 Form of Proxy IBC Corporate Information You can view our Annual Report on our website http://www.chevron.lk ICON OF STRENGTH For over 25 years, Chevron Lubricants Lanka PLC has been a symbol of corporate strength, serving the nation with excellence in lubricant products through an island-wide presence, state-of-the-art technology and the unmatched industry expertise that has kept us at the forefront of our competitive business. We experienced many challenges in 2017 by way of increased raw material costs, intense competition and unusual weather patterns which affected the lubricants industry. We’re looking ahead, with resolve and determination to continue to be an icon of strength, contributing to the nation’s economy, increasing exports and foreign revenue, generating employment, and empowering people and communities.