Leeds Studies in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harald Hardrada Invades

What happened when Edward the Confessor died? Harald Hardrada invades What do I need to know: • 5th January 1066 – Edward the Confessor dies The events of the Battles of Fulford • 6th January 1066 – Harold Godwinson crowned King of England From the moment that Harold Godwinson was crowned, he was aware that he Gate and Stamford Bridge What happened to the 4 contenders? faced a number of challenges to his throne. He marched south which part of his Why Hardrada won Fulford • William, Duke of Normandy claims the throne was promised to him army to prepare for an invasion by William. He left the rest of his army under the Why he lost Stamford Bridge. – he mobilises his troops in preparation for an invasion of Britain command of his brothers in law earls Edwin and Morcar. • Edgar Aethling considered too young to be King or challenge the Key Words: Harold prepares to strike! • Fulford gate decision • Fyrd • Harald Hardrada prepares to invade in the North • Haralf Hardrada of Norway invaded England in the September. • Hardrada • 8th September – peasant soldiers, known as the fyrd, sent home to • He sailed up the river Humber with 300 ships and landed 16 km (10 miles) from the city of • Stamford Bridge harvest the crops York. Earls Edwin and Morcar were waiting for him with the northern army and attempted to • Viking • Harald Hardrada invades the north of England prevent the Norwegian forces from advancing to York. • Earls Edwin and Morcar wait with the northern army to prevent the Were the battles significant? Norwegian forces from advancing The Battle of Stamford Bridge Significant because… However… The loss at Fulford meant that King Harold had to move quickly to deal with the Viking invasion. -

A BIT of a Au/Areness of the Events of the Battle and Promote the Sites As an Integrated Educational Resource

OUR AIMS U/orking u/ith the owners of the manij sites associated u/ith the Battle of Teu/kesburif. the Socretq aim to raise public A BIT OF A au/areness of the events of the battle and promote the sites as an integrated educational resource. U/e aim to encourage tourism and leisure activitq bq SLAP advertising, interpretation and presentation in connection u/ith the sites. U/e aim also to collate research into the battle, and to encourage further research, making the results available to the public through a varietu, of media. (n pursuing our objects, u/e hope to be working alongside a varietq of organisations, in Teu/kesburq and throughout the u/orld. U/e u/ill be proposing schemes and advocating projects, including fundraising for them and project managing if appropriate. U/e aim to become the Authority on the battle and battlesfte OUR OBJECTS To promote the permanent preservation of the battlefield and other sites associated u/ith the Battle of Teu/kesburq, 1471, as sites of historic interest, to the benefit of the public generaHq. To promote the educational and tourism possibilities of the ntw&Cttter vftfit battlefield and associated sites, particularity in relation to medieval historq. To promote, for public benefit, research into matters associated u/ith the sites, and to publish the useful results of such research. ISSUC 10: 2005 Free to members, otheru/ise £2.00 The First Word I have to confess that I was beginning to think that this edition of the 'Slap' First Word 2 would never appear in print. -

Anglo–Saxon and Norman England

GCSE HISTORY Anglo–Saxon and Norman England Module booklet. Your Name: Teacher: Target: History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 Checklist Anglo-Saxon society and the Norman conquest, 1060-66 Completed Introduction to William of Normandy 2-3 Anglo-Saxon society 4-5 Legal system and punishment 6-7 The economy and social system 8 House of Godwin 9-10 Rivalry for the throne 11-12 Battle of Gate Fulford & Stamford Bridge 13 Battle of Hastings 14-16 End of Key Topic 1 Test 17 William I in power: Securing the kingdom, 1066-87 Page Submission of the Earls 18 Castles and the Marcher Earldoms 19-20 Revolt of Edwin and Morcar, 1068 21 Edgar Aethling’s revolts, 1069 22-24 The Harrying of the North, 1069-70 25 Hereward the Wake’s rebellion, 1070-71 26 Maintaining royal power 27-28 The revolt of the Earls, 1075 29-30 End of Key Topic 2 Test 31 Norman England, 1066-88 Page The Norman feudal system 32 Normans and the Church 33-34 Everyday life - society and the economy 35 Norman government and legal system 36-38 Norman aristocracy 39 Significance of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux 40 William I and his family 41-42 William, Robert and revolt in Normandy, 1077-80 43 Death, disputes and revolts, 1087-88 44 End of Key Topic 3 test 45 1 History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 2 History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 KT1 – Anglo-Saxon society and the Normans, 1060-66 Introduction On the evening of 14 October 1066 William of Normandy stood on the battlefield of Hastings. -

Knowledge Organiser Focus: Early Migration to Britain

Knowledge Organiser Focus: Early migration to Britain I should already know: Key Words Stone Age A period lasting thousands of years, where our ancestors lived in basic homes and used What a decade, stone tools. The age ended around 2,000 BC with the use of metal. century and Hunter Gatherer A way of life in which people search or hunt for their food, not growing it. millennium is Doggerland An area of land that existed thousands of years ago. It used to connect Britain to Northern Europe I will learn: Celts A group of people who lived in Europe after the Stone age. What made many groups over time migrate (move to) Britain Roman Empire One of the largest and most powerful empires. It controlled land from North Africa to England. How the earliest settlements Dark Ages A period after the Romans left Britain. Their technology and architecture was lost. were made in Britain. Anglo Saxons People who lived in England. Their ancestors had arrived from northern Europe from the 5th century. The impact of the Roman Vikings People who raided (attacked) or settled in England from 793 AD Empire’s time ruling Britain. The Romans ruled Britain from Greater Depth Challenge How far the Anglo Saxons made 43AD to 410AD; almost four the Britain we know today. centuries How the presence of the The Saxons migrated to Britain Vikings changed Saxon life. after the Romans, until the early 600s. This will help in the future: The Vikings had been migrating Further Reading to and trying to invade Britain, This short unit will lead into The period of stone age hunter- from 793AD until 1066, when our first main year 7 unit, on gatherers lasted for thousands of years the Norman Conquest of the Norman Conquest began. -

1 Arrival of the House of Wessex the Invaders of the 5Th and 6Th

1 Arrival of the House of Wessex The invaders of the 5th and 6th Centuries famously came from 3 tribes - the Jutes, Angles and Saxons, and each formed kingdoms that eventually became the 7 English Kingdoms - or the Heptarchy. At first the Britons appealed to Rome to come back and help them. They sent a piteous note to Aetius, the last effective Roman general which read: ‘ The Barbarians push us back to the sea, the sea pushes us back to the barbarians; between these two kind of deaths we are either drowned or slaughtered’. Who was Cerdic ? The background of the founder of the British Monarchy is not simple. Cerdic is a British name, not Saxon. So who was he ? He may simply have had a British mother - and so be a Saxon with a British name. Or he may have been a local Romano British official. Or maybe he was a British prince come to seek his fortune. Cerdic arrived at the mouth of the River Test, and over the next 6 years he fought the local British kings, as you can see in the map. These culminated in the battle at Netley Marsh, where he defeated Nathanleod. Cerdic died in 534, was buried at Hurstboourne Tarrant in Hampshire, and handed the kingdom on to his Grandson, Cynric. 2: The West Saxon Bretwalda Cynric, King of Wessex 534 - 560 Cerdic's grandson, Cynric, took over the leadership on Cerdic's death. During this time the kingdom of Arthur - or some other British warlord - remained stromg. But in the 550's we see a change. -

History Knowledge Organiser Causes of the Norman Conquest

History Knowledge Organiser Causes of the Norman Conquest Key individuals Who were the Normans? England before 1066 Earl Godwin In 911, a Viking named Rollo unsuccessfully attacked northern France. Edward the Confessor Despite this, the French king offered Rollo an area of land in north west France, in exchange for his loyalty (allegiance). This area of land became Edgar the Outlaw known as Normandy. Harald Hardrada Harold Godwinson King Edward’s mother was the half sister of Duke Richard II of Normandy, William, Duke of Normandy so Edward brought many of his Norman friends over to England as advisors. This led to conflict with Earl Godwin in 1051. William, therefore was a distant cousin of Edward’s, as well as a close friend and advisor. Key dates 1042 Edward the The rivals for the throne Confessor becomes King of Rules of Edgar the Outlaw- known as the Aethling. England Inheritance The great nephew of Edward. Had the support of many Anglo-Saxon earls. 1052 Earl Godwin is Inherit directly or Harald Hardrada- believed he should be king exiled after a chosen based on prior Viking ownership of English dispute with King crown before Edward became king. Edward Post Obitum- Harold Godwinson- most powerful earl in ‘after death’ England as Earl of Wessex. Was deputy king 5th King Edward the nomination (‘sub-regulus’) in 1060. Claimed Edward January Confessor dies promised him the throne on his deathbed. 1066 Novissima Had the support of the Witan. William, Duke of Normandy- Distant cousin th verba- named 6 Harold of Edward. Claimed Edward had promised January Godwinson heir on deathbed him the throne after helping Edward with the 1066 becomes King of Godwin rebellion of 1051. -

Knowledge Organiser Focus: the Norman Conquest

Knowledge Organiser Focus: The Norman Conquest I should already know: Key Words How to plot and use a Cavalry Mounted soldiers on horseback timeline in chronological Claimant Someone believing they should be king order. Feigned Retreat Pretending to run away so that enemy is tricked into following Feudal System Hierarchy of society, with the King at the top I will learn: Fyrd Anglo-Saxon soldiers who joined the army at times of trouble. They • What life was like pre- were usually farmers and were poorly trained. 1066. • Why there was a Housecarls Full-time, well-trained Anglo-Saxon warriors succession crisis in 1066. Oath A very serious promise • The 3 main contenders for Shield Wall Overlapping shields in battle for protection the throne: Harold Godwinson, Harald Hardrada, William of Greater Depth Challenge Normandy How important was Tostig? • The events of the 3 main Tostig Godwinson: brother of battles: Gate Fulford, Harold Godwinson and Earl of Stamford Bridge, Hastings. Northumbria. He lost his • The effects of the Norman Earldom because of his Conquest including the tyrannical rule and joined Harrying of the North Edward the Confessor died in Hardrada. 1066 with no heirs, This will help in the future: leaving a disputed Further Reading succession and 3 Fact: https://www.bbc.com/bitesize Crime and Punishment through main claimants for /guides/zsjnb9q/revision/1 time the throne. This led Anglo-Saxon & Norman Britain to 3 battles taking Fiction: 1066 (I was there) by Jim place that year. Eldridge Knowledge Organiser Focus: The Norman Conquest Summarise your learning Chronology: what happened on these dates? 1043 Edward the Confessor crowned King of England Anglo- Anglo-Saxons England was Saxon a largely peaceful and 1064 Harold’s embassy to Normandy society prosperous kingdom. -

Plundering the Territories in the Manner of Heathens

Raffield, B. 2009. ‘“Plundering the Territories in the Manner of the Heathens”: Identifying Viking Age Battlefields in Britain’, Rosetta 7: 22-43. http://rosetta.bham.ac.uk/issue7/plundering-territories/ http://rosetta.bham.ac.uk/issue7/plundering-territories/ ‘Plundering the Territories in the Manner of the Heathens’: Identifying Viking Age Battlefields in Britain Benjamin Raffield University of Birmingham ‘Battle’ is a word often associated with the Viking Age in England and there are numerous references in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles to the conflict that took place as the Anglo-Saxons fought to keep Viking incursions at bay. There is no doubt that hostile encounters between the two sides were violent and bloody, with the Anglo-Saxons fighting to hold on to territories that were now not only under threat from other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, but also from ‘heathens’ and foreign enemies who were set on conquering England for their own. These battles were to take place for over two and a half centuries from the first recorded raid at Lindisfarne, Northumbria, in 793 until the famous Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. Archaeology as a discipline knows relatively little of how these people fought each other for possession of English soil and wealth. There are numerous contemporary references to battles in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, but these state little more than there being a ‘great slaughter’ at a certain location, with the victor occasionally being named. We are not sure of the size of the battles both in terms of area and the number of combatants, nor are we sure of the tactics used. -

Representations of English History in Icelandic Kings‟ Saga: Haraldssaga Hardrada and Knytlinga Saga

REPRESENTATIONS OF ENGLISH HISTORY IN ICELANDIC KINGS‟ SAGA: HARALDSSAGA HARDRADA AND KNYTLINGA SAGA A Master‟s Thesis By DENĠZ CEM GÜLEN Department of History Ġhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara August 2015 REPRESENTATIONS OF ENGLISH HISTORY IN ICELANDIC KINGS‟ SAGA: HARALDSSAGA HARDRADA AND KNYTLINGA SAGA Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of Ġhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by DENĠZ CEM GÜLEN In Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ĠHSAN DOĞRAMACI BILKENT UNIVERSTY ANKARA August 2015 Abstract REPRESENTATIONS OF ENGLISH HISTORY IN ICELANDIC KINGS‟ SAGA: HARALDSSAGA HARDRADA AND KNYTLINGA SAGA Gülen, Deniz Cem Gülen MA, Department of History Supervisor: Assistant Professor Dr. David Thornton August, 2015 The Icelandic sagas are one of the most important historical sources for Viking studies. Although there are many different types of saga, only the kings‟ sagas and family sagas are generally considered historically accurate to some extent. Unfortunately, because they were composed centuries after the Viking age, even these sagas contain a number of historical inaccuracies. In this research, I will try to discuss this problem by focusing on the Heimskringla version of King Harald‟s saga and the Knýtlinga saga, and how English history is represented in them. After discussing the nature of the sagas and the problems of the Icelandic sources, I will consider the saga accounts of certain events that occurred in England during the reigns of Harald Hardrada and Cnut the Great. In order to show the possible mistakes in these sagas, primary sources from outside of Scandinavia and Iceland, notably the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, as well as modern studies, will be used to assess these possible errors in the Heimskringla and Knýtlinga saga. -

Sample Material

A pathway to Edexcel GCSE (9-1) History Exploring History: SAMPLE Monarchs, Monks & Migrants Monarchs, MATERIAL NEW FOR 2017 Author: Lorem Ipsom www.pearsonschools.co.uk [email protected] Monarchs, Monks & Migrants Contents – Book 1 How to use this book 4 Chapter 4: The Problems of Medieval Monarchs Exploring History Historical Anachronisms 6 Who were England’s Medieval Monarchs? 104 What is Chronology? 8 How important were England’s The Process of History 10 medieval queens? 108 A pathway to Edexcel GCSE (9-1) History Medieval Timeline 12 What have we learned? Interpretations 116 How powerful were English monarchs? 118 Chapter 1: The Norman Conquest Based on the Edexcel Scheme of Work, Pearson’s brand-new What have we learned? Causation 134 What was England like before the Battle Exploring History resources for KS3 are designed to inspire of Hastings? 16 young historians and equip them with the skills and knowledge Why was England a Battlefi eld in 1066? 24 Chapter 5: The Black Death needed to go on to study Edexcel GCSE (9-1) History. What have we learned?: Causation 38 Was 1348 the end of the world? 136 Material We think our resources speak for themselves, so here’s some How did William take control of England? 40 What have we learned? Evidence 148 hot-off-the press sample material for you to browse and enjoy. What have we learned?: Evidence 48 What was it like to live in the shadow of Sample the Black Death? 150 What have we learned? Change 162 Chapter 2: Religion in Medieval England Why was the church central to people’s Chapter -

The Norman Conquest

OCR SHP GCSE THE NORMAN CONQUEST NORMAN THE OCR SHP 1065–1087 GCSE THE NORMAN MICHAEL FORDHAM CONQUEST 1065–1087 MICHAEL FORDHAM The Schools History Project Set up in 1972 to bring new life to history for school students, the Schools CONTENTS History Project has been based at Leeds Trinity University since 1978. SHP continues to play an innovatory role in history education based on its six principles: ● Making history meaningful for young people ● Engaging in historical enquiry ● Developing broad and deep knowledge ● Studying the historic environment Introduction 2 ● Promoting diversity and inclusion ● Supporting rigorous and enjoyable learning Making the most of this book These principles are embedded in the resources which SHP produces in Embroidering the truth? 6 partnership with Hodder Education to support history at Key Stage 3, GCSE (SHP OCR B) and A level. The Schools History Project contributes to national debate about school history. It strives to challenge, support and inspire 1 Too good to be true? 8 teachers through its published resources, conferences and website: http:// What was Anglo-Saxon England really like in 1065? www.schoolshistoryproject.org.uk Closer look 1– Worth a thousand words The wording and sentence structure of some written sources have been adapted and simplified to make them accessible to all pupils while faithfully preserving the sense of the original. 2 ‘Lucky Bastard’? 26 The publishers thank OCR for permission to use specimen exam questions on pages [########] from OCR’s GCSE (9–1) History B (Schools What made William a conqueror in 1066? History Project) © OCR 2016. OCR have neither seen nor commented upon Closer look 2 – Who says so? any model answers or exam guidance related to these questions. -

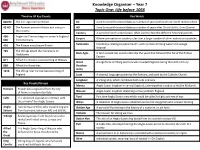

Knowledge Organiser

Knowledge Organiser – Year 7 Topic One: Life before 1066 Timeline Of Key Events Key Words 800 BC The Iron Age reaches Britain BC Used to record historical dates as number of years before Christ’s birth: Before Christ 43 AD The Romans arrive in Britain and conquer AD Used to record historical dates as number of years after Christ’s birth: Anno Domini. the country Century A period of one hundred years, often used to describe different historical periods. 400- Angles and Saxons begin to arrive in England Empire Where one nation or country rules over a large number of other nations or countries. 600 from Germany. 410 The Roman army leaves Britain Sanitation Conditions relating to public health, such as clean drinking water and sewage disposal. 793 The Vikings attack the monastery on Lindisfarne Dark Ages A term sometimes used to describe the years that followed the fall of the Roman Empire. 871 Alfred the Great is crowned King of Wessex Great A large force of Viking warriors who invaded England during the ninth century. 899 Alfred the Great dies Heathen Army 1016 The Viking ruler Canute becomes King of England Latin A classical language spoken by the Romans, and used by the Catholic Church. Longboat A Viking ship, which combined both sails and oars. Key People/Groups Mercia Anglo-Saxon kingdom in central England, covering what is today called the Midlands. Romans People who originated from the city of Rome in modern day Italy. Wessex Anglo-Saxon kingdom stretching across southern England. Celts The dominant population in Britain until Fyrd Part time Anglo-Saxon army which could be called to fight at times of war.