Plundering the Territories in the Manner of Heathens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

Beowulf and the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial

Beowulf and The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial The value of Beowulf as a window on Iron Age society in the North Atlantic was dramatically confirmed by the discovery of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial in 1939. Ne hÿrde ic cymlīcor cēol gegyrwan This is identified as the tomb of Raedwold, the Christian King of Anglia who died in hilde-wæpnum ond heaðo-wædum, 475 a.d. – about the time when it is thought that Beowulf was composed. The billum ond byrnum; [...] discovery of so much martial equipment and so many personal adornments I never yet heard of a comelier ship proved that Anglo-Saxon society was much more complex and advanced than better supplied with battle-weapons, previously imagined. Clearly its leaders had considerable wealth at their disposal – body-armour, swords and spears … both economic and cultural. And don’t you just love his natty little moustache? xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx(Beowulf, ll.38-40.) Beowulf at the movies - 2007 Part of the treasure discovered in a ship-burial of c.500 at Sutton Hoo in East Anglia – excavated in 1939. th The Sutton Hoo ship and a modern reconstruction Ornate 5 -century head-casque of King Raedwold of Anglia Caedmon’s Creation Hymn (c.658-680 a.d.) Caedmon’s poem was transcribed in Latin by the Venerable Bede in his Ecclesiatical History of the English People, the chief prose work of the age of King Alfred and completed in 731, Bede relates that Caedmon was an illiterate shepherd who composed his hymns after he received a command to do so from a mysterious ‘man’ (or angel) who appeared to him in his sleep. -

Holy (Land) Terrain Analysis 3

Holy (Land) Terrain Analysis 3 By Gordon S Fowkes, Grand Historian of the Grand Priory of St Joan of Arc of Mexico Wednesday, June 08, 2011 St Joan of Arc Disclaimer: The opinions herein are those of the author and not endorsed by the Grand Priory of of Mexico . Global Medieval War The scope of the terrain involved in the Crusades and of the Knights Templar stretches across the entire Eurasian Continent and includes North Africa. At the time the Mongols were raiding the Russian steppes and the Holy Land, they were also raiding from Vietnam to Japan and Korea. It was a world war no less than those of the Twentieth Century. Of the peoples that clashed from the corners of the Eurasian Continent everyone was touched by the wars, but a few of the larger aggregates call for special attention, These include the Vikings, Arabs, Byzantines, Franks and the Mongol-Turks. Each is a major study by themselves, but we will take the broad brush treatment. The Vikings The expansion and evolution of the Vikings as they raided and invaded is one of the great migrations of history, About the time of King Arthur, approximately, Danes, Angles, and Saxons invaded Celt- Roman Britiannia and established England. The language, Anglo-Saxon, is still the base of the English language, The last Anglo-Saxon King of England was Harold Godwinson. This brought him into conflict with the two main branches of the Vikings whose homeland is presumed to be the southern parts of Sweden and Norway plus parts of Denmark in an polity of shifting alliances. -

Harald Hardrada Invades

What happened when Edward the Confessor died? Harald Hardrada invades What do I need to know: • 5th January 1066 – Edward the Confessor dies The events of the Battles of Fulford • 6th January 1066 – Harold Godwinson crowned King of England From the moment that Harold Godwinson was crowned, he was aware that he Gate and Stamford Bridge What happened to the 4 contenders? faced a number of challenges to his throne. He marched south which part of his Why Hardrada won Fulford • William, Duke of Normandy claims the throne was promised to him army to prepare for an invasion by William. He left the rest of his army under the Why he lost Stamford Bridge. – he mobilises his troops in preparation for an invasion of Britain command of his brothers in law earls Edwin and Morcar. • Edgar Aethling considered too young to be King or challenge the Key Words: Harold prepares to strike! • Fulford gate decision • Fyrd • Harald Hardrada prepares to invade in the North • Haralf Hardrada of Norway invaded England in the September. • Hardrada • 8th September – peasant soldiers, known as the fyrd, sent home to • He sailed up the river Humber with 300 ships and landed 16 km (10 miles) from the city of • Stamford Bridge harvest the crops York. Earls Edwin and Morcar were waiting for him with the northern army and attempted to • Viking • Harald Hardrada invades the north of England prevent the Norwegian forces from advancing to York. • Earls Edwin and Morcar wait with the northern army to prevent the Were the battles significant? Norwegian forces from advancing The Battle of Stamford Bridge Significant because… However… The loss at Fulford meant that King Harold had to move quickly to deal with the Viking invasion. -

A BIT of a Au/Areness of the Events of the Battle and Promote the Sites As an Integrated Educational Resource

OUR AIMS U/orking u/ith the owners of the manij sites associated u/ith the Battle of Teu/kesburif. the Socretq aim to raise public A BIT OF A au/areness of the events of the battle and promote the sites as an integrated educational resource. U/e aim to encourage tourism and leisure activitq bq SLAP advertising, interpretation and presentation in connection u/ith the sites. U/e aim also to collate research into the battle, and to encourage further research, making the results available to the public through a varietu, of media. (n pursuing our objects, u/e hope to be working alongside a varietq of organisations, in Teu/kesburq and throughout the u/orld. U/e u/ill be proposing schemes and advocating projects, including fundraising for them and project managing if appropriate. U/e aim to become the Authority on the battle and battlesfte OUR OBJECTS To promote the permanent preservation of the battlefield and other sites associated u/ith the Battle of Teu/kesburq, 1471, as sites of historic interest, to the benefit of the public generaHq. To promote the educational and tourism possibilities of the ntw&Cttter vftfit battlefield and associated sites, particularity in relation to medieval historq. To promote, for public benefit, research into matters associated u/ith the sites, and to publish the useful results of such research. ISSUC 10: 2005 Free to members, otheru/ise £2.00 The First Word I have to confess that I was beginning to think that this edition of the 'Slap' First Word 2 would never appear in print. -

Anglo–Saxon and Norman England

GCSE HISTORY Anglo–Saxon and Norman England Module booklet. Your Name: Teacher: Target: History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 Checklist Anglo-Saxon society and the Norman conquest, 1060-66 Completed Introduction to William of Normandy 2-3 Anglo-Saxon society 4-5 Legal system and punishment 6-7 The economy and social system 8 House of Godwin 9-10 Rivalry for the throne 11-12 Battle of Gate Fulford & Stamford Bridge 13 Battle of Hastings 14-16 End of Key Topic 1 Test 17 William I in power: Securing the kingdom, 1066-87 Page Submission of the Earls 18 Castles and the Marcher Earldoms 19-20 Revolt of Edwin and Morcar, 1068 21 Edgar Aethling’s revolts, 1069 22-24 The Harrying of the North, 1069-70 25 Hereward the Wake’s rebellion, 1070-71 26 Maintaining royal power 27-28 The revolt of the Earls, 1075 29-30 End of Key Topic 2 Test 31 Norman England, 1066-88 Page The Norman feudal system 32 Normans and the Church 33-34 Everyday life - society and the economy 35 Norman government and legal system 36-38 Norman aristocracy 39 Significance of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux 40 William I and his family 41-42 William, Robert and revolt in Normandy, 1077-80 43 Death, disputes and revolts, 1087-88 44 End of Key Topic 3 test 45 1 History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 2 History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 KT1 – Anglo-Saxon society and the Normans, 1060-66 Introduction On the evening of 14 October 1066 William of Normandy stood on the battlefield of Hastings. -

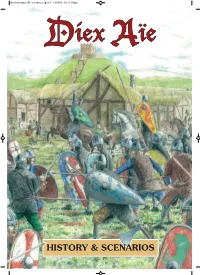

Cry Havoc Règles Fr 13/09/16 16:33 Page1 Diex Aïe

diex historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 13/09/16 16:33 Page1 Diex Aïe HISTORY & SCENARIOS diex historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 13/09/16 16:33 Page2 © BUxeria & Historic’One éditions - 2016 - v1.1 diex historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 13/09/16 16:33 Page1 Historical Background The Norman Conquest of England - 1066/1086 1 - The days following Hastings 1.1 - Aftermath of the battle October 14, 1066, 5:00PM: Harold is killed by an arrow, or perhaps a groUp of Norman knights, opinions still differ on this issUe. The news of the death of the last Saxon king spreads on the battlefield, and the Saxons begin to withdraw. William knows he mUst eliminate as many Saxon fighters as possible and laUnches the pUrsUit. However, the retreat does not tUrn into a roUt. Late into the night, north of Senlac, intense reargUard fighting continUes. Withdrawing elements and reinforcements arriving late at the battle continUe a fierce resistance. Among these fights is the one the Normans call Malefosse, where many knights are killed in a ditch while darkness prevails. BUt these fights coUld no longer change what happened at Hastings. William had jUst won a decisive victory. 1.2 - The march towards London Initially, the DUke of Normandy secUres this bridgehead and seizes Dover withoUt mUch Campaign of 1066 resistance. He sends troops en roUte to pUnish the town of Old Romney, jUst east of Hastings, Berkhamsted whose inhabitants had killed the crew of two OxfordOxford London stray Norman ships. Given the losses in (December 25) Hastings, William avoids rUshing to London. -

British Royal Ancestry Book 6, Kings of England from King Alfred the Great to Present Time

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY BRITISH ROYAL ANCESTRY, BOOK 6 Kings of England INTRODUCTION The British ancestry is very much a patchwork of various beginnings. Until King Alfred the Great established England various Kings ruled separate parts. In most cases the initial ruler came from the mainland. That time of the history is shrouded in myths, which turn into legends and subsequent into history. Alfred the Great (849-901) was a very learned man and studied all available past history and especially biblical information. He came up with the concept that he was the 72nd generation descendant of Adam and Eve. Moreover he was a 17th generation descendant of Woden (Odin). Proponents of one theory claim that he was the descendant of Noah’s son Sem (Shem) because he claimed to descend from Sceaf, a marooned man who came to Britain on a boat after a flood. (See the Biblical Ancestry and Early Mythology Ancestry books). The book British Mythical Royal Ancestry from King Brutus shows the mythical kings including Shakespeare’s King Lair. The lineages are from a common ancestor, Priam King of Troy. His one daughter Troana leads to us via Sceaf, the descendants from his other daughter Creusa lead to the British linage. No attempt has been made to connect these rulers with the historical ones. Before Alfred the Great formed a unified England several Royal Houses ruled the various parts. Not all of them have any clear lineages to the present times, i.e. our ancestors, but some do. I have collected information which shows these. They include; British Royal Ancestry Book 1, Legendary Kings from Brutus of Troy to including King Leir. -

Thevikingblitzkriegad789-1098.Pdf

2 In memory of Jeffrey Martin Whittock (1927–2013), much-loved and respected father and papa. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A number of people provided valuable advice which assisted in the preparation of this book; without them, of course, carrying any responsibility for the interpretations offered by the book. We are particularly indebted to our agent Robert Dudley who, as always, offered guidance and support, as did Simon Hamlet and Mark Beynon at The History Press. In addition, Bradford-on-Avon library, and the Wiltshire and the Somerset Library services, provided access to resources through the inter-library loans service. For their help and for this service we are very grateful. Through Hannah’s undergraduate BA studies and then MPhil studies in the department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic (ASNC) at Cambridge University (2008–12), the invaluable input of many brilliant academics has shaped our understanding of this exciting and complex period of history, and its challenging sources of evidence. The resulting familiarity with Old English, Old Norse and Insular Latin has greatly assisted in critical reflection on the written sources. As always, the support and interest provided by close family and friends cannot be measured but is much appreciated. And they have been patient as meal-time conversations have given way to discussions of the achievements of Alfred and Athelstan, the impact of Eric Bloodaxe and the agendas of the compilers of the 4 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 5 CONTENTS Title Dedication Acknowledgements Introduction 1 The Gathering -

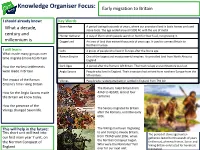

Knowledge Organiser Focus: Early Migration to Britain

Knowledge Organiser Focus: Early migration to Britain I should already know: Key Words Stone Age A period lasting thousands of years, where our ancestors lived in basic homes and used What a decade, stone tools. The age ended around 2,000 BC with the use of metal. century and Hunter Gatherer A way of life in which people search or hunt for their food, not growing it. millennium is Doggerland An area of land that existed thousands of years ago. It used to connect Britain to Northern Europe I will learn: Celts A group of people who lived in Europe after the Stone age. What made many groups over time migrate (move to) Britain Roman Empire One of the largest and most powerful empires. It controlled land from North Africa to England. How the earliest settlements Dark Ages A period after the Romans left Britain. Their technology and architecture was lost. were made in Britain. Anglo Saxons People who lived in England. Their ancestors had arrived from northern Europe from the 5th century. The impact of the Roman Vikings People who raided (attacked) or settled in England from 793 AD Empire’s time ruling Britain. The Romans ruled Britain from Greater Depth Challenge How far the Anglo Saxons made 43AD to 410AD; almost four the Britain we know today. centuries How the presence of the The Saxons migrated to Britain Vikings changed Saxon life. after the Romans, until the early 600s. This will help in the future: The Vikings had been migrating Further Reading to and trying to invade Britain, This short unit will lead into The period of stone age hunter- from 793AD until 1066, when our first main year 7 unit, on gatherers lasted for thousands of years the Norman Conquest of the Norman Conquest began. -

Yorkshire Battles

A 77 ( LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF YORKSHIRE BATTLES. YORKSHIRE BATTLES BY EDWARD LAMPLOUGH, AUTHOR OF "THE SIEGE OF HULL," "MEDIAEVAL YORKSHIRE,' "HULL AND YORKSHIRE FRESCOES," ETC. HULL: WILLIAM ANDREWS & CO. LONDON : SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT & Co., LIMITED. 1891. HULL : WILLIAM ANDREWS AND CO. PRINTERS, DOCK STREET. To TIIK REV. E. G. CHARLESWORTH, VICAR OF ACKLAM, A CONTRIBUTOR TO AND LOVER OF YORKSHIRE LITERATURE, is Dolume IS MOST RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED. E. L. Contents. I'AGE I. WlNWIDFIELD, ETC. I II. BATTLE OK STAMFORD BRIDGE ... ... ... 15 III. AFTER STAMFORD BRIDGE 36 IV. BATTLE OF THE STANDARD ... ... ... .. 53 V. AFTER THE BATTLE OF THE STANDARD 75 VI. BATTLE OF MYTON MEADOWS ; 83 VII. BATTLE OF BOROUGHBRIDGE ... ... ... ... 101 VIII. BATTLE OF BYLAND ABBEY ... ... ... ... 116 IX. IN THE DAYS OF EDWARD III. AND RICHARD II. 131 X. BATTLE OF BRAMHAM MOOR 139 XI. BATTLE OF SANDAL 150 XII. BATTLE OF TOWTON ... ... ... ... ... 165 XIII. YORKSHIRE UNDER THE TUDORS ... ... ... 173 XIV. BATTLE OF TADCASTER ... ... ... ... ... 177 XV. BATTLE OF LEEDS 183 XVI. BATTLE OF WAKEFIELD ... ... ... ... ... 187 XVII. BATTLE OF ADWALTON MOOR ... ... ... ... 192 XVIII. BATTLE OF HULL 196 XIX. BATTLE OF SELBY 199 XX. BATTLE OF MARSTON MOOR ... ... ... ... 203 XXI. BATTLE OF BRUNNANBURGH 216 XXII. FIGHT OFF FLAMBOROUGH HEAD ... ... ... 221 INDEX 227 preface. T X the history of our national evolution York- shire occupies a most important position, and the sanguinary record of Yorkshire Battles possesses something more than material for the poet and the artist. Valour, loyalty, patriotism, honour and self-sacrifice are virtues not uncommon to the warrior, and the blood of true and brave men has liberally bedewed our fields. -

1 Arrival of the House of Wessex the Invaders of the 5Th and 6Th

1 Arrival of the House of Wessex The invaders of the 5th and 6th Centuries famously came from 3 tribes - the Jutes, Angles and Saxons, and each formed kingdoms that eventually became the 7 English Kingdoms - or the Heptarchy. At first the Britons appealed to Rome to come back and help them. They sent a piteous note to Aetius, the last effective Roman general which read: ‘ The Barbarians push us back to the sea, the sea pushes us back to the barbarians; between these two kind of deaths we are either drowned or slaughtered’. Who was Cerdic ? The background of the founder of the British Monarchy is not simple. Cerdic is a British name, not Saxon. So who was he ? He may simply have had a British mother - and so be a Saxon with a British name. Or he may have been a local Romano British official. Or maybe he was a British prince come to seek his fortune. Cerdic arrived at the mouth of the River Test, and over the next 6 years he fought the local British kings, as you can see in the map. These culminated in the battle at Netley Marsh, where he defeated Nathanleod. Cerdic died in 534, was buried at Hurstboourne Tarrant in Hampshire, and handed the kingdom on to his Grandson, Cynric. 2: The West Saxon Bretwalda Cynric, King of Wessex 534 - 560 Cerdic's grandson, Cynric, took over the leadership on Cerdic's death. During this time the kingdom of Arthur - or some other British warlord - remained stromg. But in the 550's we see a change.