Tidal Marshes Are Either Exposed to the Open Bay Or Are Protected from Wave and Tidal Energy by Offshore Mudflats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2011 510 520 3876

BPWA Walks Walks take place rain or shine and last 2-3 hours unless otherwise noted. They are free and Berkeley’s open to all. Walks are divided into four types: Theme Friendly Power Self Guided Questions about the walks? Contact Keith Skinner: [email protected] Vol. 14 No. 3 BerkeleyPaths Path Wanderers Association Fall 2011 510 520 3876. October 9, Sunday - 2nd An- BPWA Annual Meeting Oct. 20 nual Long Walk - 9 a.m. Leaders: Keith Skinner, Colleen Neff, To Feature Greenbelt Alliance — Sandy Friedland Sandy Friedland Can the Bay Area continue to gain way people live.” A graduate of Stanford Meeting Place: El Cerrito BART station, University, Matt worked for an envi- main entrance near Central population without sacrificing precious Transit: BART - Richmond line farmland, losing open space and harm- ronmental group in Sacramento before All day walk that includes portions of Al- ing the environment? The members of he joined Greenbelt. His responsibilities bany Hill, Pt. Isabel, Bay Trail, Albany Bulb, Greenbelt Alliance are doing everything include meeting with city council members East Shore Park, Aquatic Park, Sisterna they can to answer those questions with District, and Santa Fe Right-of-Way, ending a resounding “Yes.” Berkeley Path at North Berkeley BART. See further details Wanderers Asso- in the article on page 2. Be sure to bring a ciation is proud to water bottle and bag lunch. No dogs, please. feature Greenbelt October 22, Saturday - Bay Alliance at our Trail Exploration on New Landfill Annual Meeting Thursday, October Loop - 9:30 a.m. 20, at the Hillside Club (2286 Cedar Leaders: Sandra & Bruce Beyaert. -

Chapter 4.4 Cultural Resources

Section 4.4 Cultural Resources 4.4 CULTURAL RESOURCES 4.4.1 Introduction This section presents information on known and potentially existing cultural resources at the RBC site and analyzes the potential for development under the proposed 2014 LRDP to affect those resources. Information and analysis in this section is based on previous archaeological surveys (see Section 4.4.5) and those conducted for the current project: Cultural Resources Inventory Report for the Richmond Bay Campus, Alameda County (GANDA 2013) and Historic Properties Survey Report for Richmond Bay Campus (Tetra Tech 2013). Cultural resources can be prehistoric, Native American, or historic. Prehistoric resources are artifacts from human activities that predate written records; these are generally identified in isolated finds or sites. Prehistoric resources are typically archaeological and can include village sites, temporary camps, lithic scatters, roasting pits/hearths, milling features, petroglyphs, rock features, and burial plots. Historic resources are properties, structures, or built items from human activities that coincide with the epoch of written records. Historic resources can include archaeological remains and architectural structures. Historic archaeological sites include townsites, homesteads, agricultural or ranching features, mining-related features, refuse concentrations, and features or artifacts associated with early military and industrial land uses. Historic architectural resources can include houses, cabins, barns, lighthouses, other constructed buildings, and bridges. Generally, architectural resources that are over 50 years old are considered for evaluation for their historic significance. Public and agency NOP comments related to cultural resources are summarized below: For construction activities proposed in a state right-of-way, Caltrans requires that project environmental documentation include results of a current Northwest Information Center archaeological records search. -

Proposal for Pillar Point Rvpark Public Restroom and Green Space Design,Engineering,Permitting

PPRROOPPOOSSAALL FFOORR PPIILLLLAARR PPOOIINNTT RRVV PPAARRKK PPUUBBLLIICC RREESSTTRROOOOMM AANNDD GGRREEEENN SSPPAACCEE DDEESSIIGGNN,, EENNGGIINNEEEERRIINNGG,, PPEERRMMIITTTTIINNGG AANNDD CCOONNSSTTRRUUCCTTIIOONN SSUUPPPPOORRTT SSEERRVVIICCEESS Submitted to: San Mateo County Harbor District Submitted by: Questa Engineering Corporation In Association with: Ware Associates Zeiger Engineers, Inc. mack5 October 7, 2019 October 7, 2019 San Mateo County Harbor District Attn: Deputy Secretary of the District 504 Ave Alhambra, Ste. 200 El Granada, CA 94018 Subject: Proposal for Pillar Point RV Park Public Restroom and Green Space Design, Engineering, Permitting and Construction Support Services Dear Mr. Moren: Questa Engineering Corporation is pleased to present this Proposal for the Pillar Point Project. We have assembled a highly qualified team, including Ware Associates (architecture/engineering services), Zeiger Engineers, Inc. (electrical engineering), and mack5 (cost estimating). Questa is widely recognized as one of California’s leading park and trail planning and engineering design firms for open space and natural park areas in constrained and challenging sites, including coastal and beach areas. We also have extensive experience in trail planning and design in parks, and sites with complex environmental and geotechnical issues. Questa provides complete services in planning, landscape architecture and engineering design of recreational improvement projects, from preliminary engineering investigations/feasibility studies and constraints -

Bothin Marsh 46

EMERGENT ECOLOGIES OF THE BAY EDGE ADAPTATION TO CLIMATE CHANGE AND SEA LEVEL RISE CMG Summer Internship 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Research Introduction 2 Approach 2 What’s Out There Regional Map 6 Site Visits ` 9 Salt Marsh Section 11 Plant Community Profiles 13 What’s Changing AUTHORS Impacts of Sea Level Rise 24 Sarah Fitzgerald Marsh Migration Process 26 Jeff Milla Yutong Wu PROJECT TEAM What We Can Do Lauren Bergenholtz Ilia Savin Tactical Matrix 29 Julia Price Site Scale Analysis: Treasure Island 34 Nico Wright Site Scale Analysis: Bothin Marsh 46 This publication financed initiated, guided, and published under the direction of CMG Landscape Architecture. Conclusion Closing Statements 58 Unless specifically referenced all photographs and Acknowledgments 60 graphic work by authors. Bibliography 62 San Francisco, 2019. Cover photo: Pump station fronting Shorebird Marsh. Corte Madera, CA RESEARCH INTRODUCTION BREADTH As human-induced climate change accelerates and impacts regional map coastal ecologies, designers must anticipate fast-changing conditions, while design must adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change. With this task in mind, this research project investigates the needs of existing plant communities in the San plant communities Francisco Bay, explores how ecological dynamics are changing, of the Bay Edge and ultimately proposes a toolkit of tactics that designers can use to inform site designs. DEPTH landscape tactics matrix two case studies: Treasure Island Bothin Marsh APPROACH Working across scales, we began our research with a broad suggesting design adaptations for Treasure Island and Bothin survey of the Bay’s ecological history and current habitat Marsh. -

Distribution and Abundance

DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE IN RELATION TO HABITAT AND LANDSCAPE FEATURES AND NEST SITE CHARACTERISTICS OF CALIFORNIA BLACK RAIL (Laterallus jamaicensis coturniculus) IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY ESTUARY FINAL REPORT To the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service March 2002 Hildie Spautz* and Nadav Nur, PhD Point Reyes Bird Observatory 4990 Shoreline Highway Stinson Beach, CA 94970 *corresponding author contact: [email protected] PRBO Black Rail Report to FWS 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY We conducted surveys for California Black Rails (Laterallus jamaicensis coturniculus) at 34 tidal salt marshes in San Pablo Bay, Suisun Bay, northern San Francisco Bay and western Marin County in 2000 and 2001 with the aims of: 1) providing the best current information on distribution and abundance of Black Rails, marsh by marsh, and total population size per bay region, 2) identifying vegetation, habitat, and landscape features that predict the presence of black rails, and 3) summarizing information on nesting and nest site characteristics. Abundance indices were higher at 8 marshes than in 1996 and earlier surveys, and lower in 4 others; with two showing no overall change. Of 13 marshes surveyed for the first time, Black Rails were detected at 7 sites. The absolute density calculated using the program DISTANCE averaged 2.63 (± 1.05 [S.E.]) birds/ha in San Pablo Bay and 3.44 birds/ha (± 0.73) in Suisun Bay. At each survey point we collected information on vegetation cover and structure, and calculated landscape metrics using ArcView GIS. We analyzed Black Rail presence or absence by first analyzing differences among marshes, and then by analyzing factors that influence detection of rails at each survey station. -

San Francisco Bay Joint Venture

The San Francisco Bay Joint Venture Management Board Bay Area Audubon Council Bay Area Open Space Council Bay Conservation and Development Commission The Bay Institute The San Francisco Bay Joint Venture Bay Planning Coalition California State Coastal Conservancy Celebrating years of partnerships protecting wetlands and wildlife California Department of Fish and Game California Resources Agency 15 Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge Contra Costa Mosquito and Vector Control District Ducks Unlimited National Audubon Society National Fish and Wildlife Foundation NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Natural Resources Conservation Service Pacific Gas and Electric Company PRBO Conservation Science SF Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board San Francisco Estuary Partnership Save the Bay Sierra Club U.S. Army Corps of Engineers U.S. Environmental Protection Agency U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Geological Survey Wildlife Conservation Board 735B Center Boulevard, Fairfax, CA 94930 415-259-0334 www.sfbayjv.org www.yourwetlands.org The San Francisco Bay Area is breathtaking! As Chair of the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture, I would like to personally thank our partners It’s no wonder so many of us live here – 7.15 million of us, according to the 2010 census. Each one of us has our for their ongoing support of our critical mission and goals in honor of our 15 year anniversary. own mental image of “the Bay Area.” For some it may be the place where the Pacific Ocean flows beneath the This retrospective is a testament to the significant achievements we’ve made together. I look Golden Gate Bridge, for others it might be somewhere along the East Bay Regional Parks shoreline, or from one forward to the next 15 years of even bigger wins for wetland habitat. -

Native Oyster Reef Construction Underway in Richmond San

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Taylor Samuelson [email protected] 510-286-4182 April 19, 2019 Native Oyster Reef Construction Underway in Richmond San Francisco Bay Living Shorelines Project 350 Reef Structures will become habitat for Native Oysters and Pacific Herring Richmond, CA - From April 9-30, 350 oyster reef elements are being placed in nearshore areas to create a living shoreline near Giant Marsh at Point Pinole Regional Shoreline managed by East Bay Regional Park District in the City of Richmond. Eelgrass beds will be planted next to the reefs in the following weeks to create a habitat ideal for the recruitment of native Olympia oysters and other aquatic species. Living shorelines use nature-based infrastructure to create shoreline buffers that reduce the impacts from sea level rise and erosion, while creating habitat for fish and wildlife. Though a relatively new climate adaptation technique, living shorelines are proving to be an effective approach to protecting coastal resources and shoreline communities. The Giant Marsh project is one of a small number of living shoreline trial projects taking place in the San Francisco Bay, but is the only one that connects the submerged underwater habitats with adjacent wetlands and upland ecotone plant communities. This innovative demonstration project is testing a combined living shorelines approach with habitat elements at different tidal elevations at the same site, with a goal of encouraging other cities and partners to undertake this kind of climate adaptation habitat restoration project at additional sites in the bay. The multi-habitat project at Giant Marsh builds on lessons learned from the Coastal Conservancy’s living shoreline project constructed directly across the bay in San Rafael in 2012, which included the construction of oyster reefs and eelgrass beds. -

Baxter Creek Gateway Park Restoration a Post-Project Appraisal

Baxter Creek Gateway Park Restoration A Post-project appraisal University of California, Berkeley LD ARCH 227 - Restoration of Rivers and Streams By: Yiwen Chen Yuanshuo Pi Dec 16, 2019 1 Abstract This paper is seeking to evaluate the results of the Baxter Creek Gateway Restoration Project located in an urbanized section of Baxter Creek, northern El Cerrito, California, and figure out how the channel transforms and how it impacts the site and its surroundings. We appraisal the project by the condition of the creek bed and bank, vegetation, water management and public accessibility. Making a comparison of 2006 and 2019 status of the creek to figure out how the stream performed and transformed in the last 13 years. Moreover, depending on the analysis of the water catchment area, planting evolvement, space quality to study the impact of the project for the surrounding area. In the end, we devote to discuss the possibilities of improvement of the site by studying other similar precedents, trying to explore the future design directions of river restoration projects. 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Site location & History Baxter Creek Gateway Restoration project is located in El Cerrito (Figure 1.1.1). The site is located on 1.6 acres of land and is 700 feet long, consisting of a branch of one of the three tributaries of Baxter Creek (Figures 1.1.2 and 1.1.3). [1] The City of El Cerrito hired Hanford Applied Restoration Conservation contractors in 2005 to restore the creek and construct a new civic gathering area facing San Pablo Ave. -

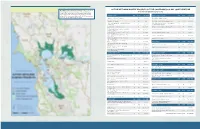

Active Wetland Habitat Projects of the San

ACTIVE WETLAND HABITAT PROJECTS OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY JOINT VENTURE The SFBJV tracks and facilitates habitat protection, restoration, and enhancement projects throughout the nine Bay Area Projects listed Alphabetically by County counties. This map shows where a variety of active wetland habitat projects with identified funding needs are currently ALAMEDA COUNTY MAP ACRES FUND. NEED MARIN COUNTY (continued) MAP ACRES FUND. NEED underway. For a more comprehensive list of all the projects we track, visit: www.sfbayjv.org/projects.php Alameda Creek Fisheries Restoration 1 NA $12,000,000 McInnis Marsh Habitat Restoration 33 180 $17,500,000 Alameda Point Restoration 2 660 TBD Novato Deer Island Tidal Wetlands Restoration 34 194 $7,000,000 Coyote Hills Regional Park - Restoration and Public Prey enhancement for sea ducks - a novel approach 3 306 $12,000,000 35 3.8 $300,000 Access Project to subtidal habitat restoration Hayward Shoreline Habitat Restoration 4 324 $5,000,000 Redwood Creek Restoration at Muir Beach, Phase 5 36 46 $8,200,000 Hoffman Marsh Restoration Project - McLaughlin 5 40 $2,500,000 Spinnaker Marsh Restoration 37 17 $3,000,000 Eastshore State Park Intertidal Habitat Improvement Project - McLaughlin 6 4 $1,000,000 Tennessee Valley Wetlands Restoration 38 5 $600,000 Eastshore State Park Martin Luther King Jr. Regional Shoreline - Water 7 200 $3,000,000 Tiscornia Marsh Restoration 39 16 $1,500,000 Quality Project Oakland Gateway Shoreline - Restoration and 8 200 $12,000,000 Tomales Dunes Wetlands 40 2 $0 Public Access Project Off-shore Bird Habitat Project - McLaughlin 9 1 $1,500,000 NAPA COUNTY MAP ACRES FUND. -

Wildcat Creek Restoration Action Plan Version 1.3 April 26, 2010 Prepared by the URBAN CREEKS COUNCIL for the WILDCAT-SAN PABLO WATERSHED COUNCIL

wildcat creek restoration action plan version 1.3 April 26, 2010 prepared by THE URBAN CREEKS COUNCIL for the WILDCAT-SAN PABLO WATERSHED COUNCIL Adopted by the City of San Pablo on August 3, 2010 wildcat creek restoration action plan table of contents 1. INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 plan obJectives 5 1.2 scope 6 Urban Urban 1.5 Methods 8 1.5 Metadata c 10 reeks 2. WATERSHED OVERVIEW 12 c 2.1 introdUction o 12 U 2.2 watershed land Use ncil 13 2.3 iMpacts of Urbanized watersheds 17 april 2.4 hydrology 19 2.5 sediMent transport 22 2010 2.6 water qUality 24 2.7 habitat 26 2.8 flood ManageMent on lower wildcat creek 29 2.9 coMMUnity 32 3. PROJECT AREA ANALYSIS 37 3.1 overview 37 3.2 flooding 37 3.4 in-streaM conditions 51 3.5 sUMMer fish habitat 53 3.6 bioassessMent 57 4. RECOMMENDED ACTIONS 58 4.1 obJectives, findings and strategies 58 4.2 recoMMended actions according to strategy 61 4.3 streaM restoration recoMMendations by reach 69 4.4 recoMMended actions for phase one reaches 73 t 4.5 phase one flood daMage redUction reach 73 able of 4.6 recoMMended actions for watershed coUncil 74 c ontents version 1.3 april 26, 2010 2 wildcat creek restoration action plan Urban creeks coUncil april 2010 table of contents 3 figUre 1-1: wildcat watershed overview to Point Pinole Regional Shoreline wildcat watershed existing trail wildcat creek highway railroad city of san pablo planned trail other creek arterial road bart Parkway SAN PABLO Richmond BAY Avenue San Pablo Point UP RR San Pablo WEST COUNTY BNSF RR CITY OF LANDFILL NORTH SAN PABLO RICHMOND San Pablo -

REQUEST for QUALIFICATIONS and PROPOSALS Notice of Development Opportunity Historic Anitas Building: 920 Macdonald Ave

REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS AND PROPOSALS Notice of Development Opportunity Historic Anitas Building: 920 Macdonald Ave. Macdonald Ave. and 11th St. - 1940’s Source: Online Archive of California City of Richmond, California Issued by the City of Richmond, CA City Manager’s Office, Development Services Submission Deadline: May 3, 2019 at 12:00 PM (PDT) City of Richmond, CA REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS AND PROPOSALS Notice of Development Opportunity 920 Macdonald Ave. City of Richmond, California City Council Mayor Tom Butt Vice Mayor Melvin Willis Councilmember Nathaniel Bates Councilmember Ben Choi Councilmember Eduardo Martinez Councilmember Jael Myrick Councilmember Demnlus Johnson III City Manager Carlos Martinez City Manager Bill Lindsay Stay updated on all Richmond Opportunity Sites: http://www.ci.richmond.ca.us/OpportunitySites Request for Qualifications/Request for Proposals: 920 Macdonald Ave. 2 City of Richmond, CA Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................... 4 II. NEIGHBORHOOD & COMMUNITY ASSETS............................. 6 III. SITE VISION...................................................................................... 21 IV. SITE AND PARCEL SUMMARY...................................................... 23 V. DEVELOPMENT TEAM SELECTION............................................ 29 VI. SUBMITTAL REQUIREMENTS..................................................... 30 VII. SELECTION CRITERIA, PROCESS & SCHEDULE.................. 33 VIII. CITY NON-LIABILITY & RELATED MATTERS.................... -

Pt. Isabel-Stege Area

Tales of the Bay Shore -- Pt. Isabel-Stege area Geology: The “bones” of the shoreline from Albany to Richmond are a sliver of ancient, alien sea floor, caught on the edge of North America as it overrode the Pacific. Fleming Point (site of today’s racetrack), Albany Hill, Pt. Isabel, Brooks Island, scattered hillocks inland, the hills at Pt Richmond, and the hills across the San Pablo Strait (spanned by the Richmond Bridge) all are part of this Novato Terrane. Erosion and uplift eventually left their hard rock as hilltops in a valley. Still later – only about 5000 years ago -- rising seas from the melting glaciers of our last Ice Age flooded the valley, forming today’s San Francisco Bay. The “alien” hilltops became islands, peninsulas linked to shore by marsh, or isolated dome-like “turtlebacks.” Left: Portion of 1911 map of SF Bay showing many Native American sites near Pt. Isabel and Stege. Right: 1853 U.S. Coastal Survey map showing N. end of Albany Hill, Cerrito Creek, Pt. Isabel, and marshes/ to North. Native Americans: Native Americans would have watched the slow rise of today’s Bay. When Europeans reached North America, the East Bay was the home of Huchiun Ohlone peoples. Living in groups generally of fewer than 100 people, they moved seasonally amid rich and varied resources, gathering, hunting, fishing, and encouraging useful plants with pruning and burning. They made reed boats, baskets, nets, traps, mortars, and a wide variety of implements and decorations. Along the shellfish-rich shoreline they gradually built up substantial hills of debris – shell mounds -- that kept them above floods and served as multipurpose homesites, burial sites, refuse dumps, and more.