Chapter 4.4 Cultural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2011 510 520 3876

BPWA Walks Walks take place rain or shine and last 2-3 hours unless otherwise noted. They are free and Berkeley’s open to all. Walks are divided into four types: Theme Friendly Power Self Guided Questions about the walks? Contact Keith Skinner: [email protected] Vol. 14 No. 3 BerkeleyPaths Path Wanderers Association Fall 2011 510 520 3876. October 9, Sunday - 2nd An- BPWA Annual Meeting Oct. 20 nual Long Walk - 9 a.m. Leaders: Keith Skinner, Colleen Neff, To Feature Greenbelt Alliance — Sandy Friedland Sandy Friedland Can the Bay Area continue to gain way people live.” A graduate of Stanford Meeting Place: El Cerrito BART station, University, Matt worked for an envi- main entrance near Central population without sacrificing precious Transit: BART - Richmond line farmland, losing open space and harm- ronmental group in Sacramento before All day walk that includes portions of Al- ing the environment? The members of he joined Greenbelt. His responsibilities bany Hill, Pt. Isabel, Bay Trail, Albany Bulb, Greenbelt Alliance are doing everything include meeting with city council members East Shore Park, Aquatic Park, Sisterna they can to answer those questions with District, and Santa Fe Right-of-Way, ending a resounding “Yes.” Berkeley Path at North Berkeley BART. See further details Wanderers Asso- in the article on page 2. Be sure to bring a ciation is proud to water bottle and bag lunch. No dogs, please. feature Greenbelt October 22, Saturday - Bay Alliance at our Trail Exploration on New Landfill Annual Meeting Thursday, October Loop - 9:30 a.m. 20, at the Hillside Club (2286 Cedar Leaders: Sandra & Bruce Beyaert. -

San Francisco Bay Joint Venture

The San Francisco Bay Joint Venture Management Board Bay Area Audubon Council Bay Area Open Space Council Bay Conservation and Development Commission The Bay Institute The San Francisco Bay Joint Venture Bay Planning Coalition California State Coastal Conservancy Celebrating years of partnerships protecting wetlands and wildlife California Department of Fish and Game California Resources Agency 15 Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge Contra Costa Mosquito and Vector Control District Ducks Unlimited National Audubon Society National Fish and Wildlife Foundation NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Natural Resources Conservation Service Pacific Gas and Electric Company PRBO Conservation Science SF Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board San Francisco Estuary Partnership Save the Bay Sierra Club U.S. Army Corps of Engineers U.S. Environmental Protection Agency U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Geological Survey Wildlife Conservation Board 735B Center Boulevard, Fairfax, CA 94930 415-259-0334 www.sfbayjv.org www.yourwetlands.org The San Francisco Bay Area is breathtaking! As Chair of the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture, I would like to personally thank our partners It’s no wonder so many of us live here – 7.15 million of us, according to the 2010 census. Each one of us has our for their ongoing support of our critical mission and goals in honor of our 15 year anniversary. own mental image of “the Bay Area.” For some it may be the place where the Pacific Ocean flows beneath the This retrospective is a testament to the significant achievements we’ve made together. I look Golden Gate Bridge, for others it might be somewhere along the East Bay Regional Parks shoreline, or from one forward to the next 15 years of even bigger wins for wetland habitat. -

Hydrologic Investigation of Concrete Flood Control Channel at UC Berkeley’S Richmond Field Station

Hydrologic Investigation of Concrete Flood Control Channel at UC Berkeley’s Richmond Field Station by Patrick Nichols Abstract The Richmond Field Station Natural Restoration Project is a five year multimillion dollar effort. The first stages involve the remediation of polluted marsh lands, then the restoration of the upland prairie habitat, finishing with the adjacent channel. The concrete flood control channel is slated to become a free flowing creek and riparian corridor by the restoration planners at the university. The dynamics of this system must be understood to properly design a restoration, or creation plan since historically no creek existed there. This study assesses multiple aspects of the concrete channel to determine its health and qualifications for restoration. We calculated flow measurements at various intervals along the channel using velocity observations and the known cross sectional areas. We observed the depths creating a predictive relationship between depth and flow. Water quality characteristics: dissolved oxygen, turbidity, and conductivity were measured on a weekly basis for three months during the winter/spring of 2004. This information is used to help answer the question of what is the health of this system with regards to these variables, and what are its hydrological characteristics. Results show a consistent base flow of about 1 cubic foot per second with a peak flow around 152cfs. A linear relationship exists between depth and flow. The slope of the channel water surface is about 0.36%. The water quality parameters were indicative of a healthy system. The results of this project provide a base of knowledge for future investigation. -

December 15, 2020

RICHMOND, CALIFORNIA, December 15, 2020 The Richmond City Council Evening Open Session was called to order at 5:02 p.m. by Mayor Thomas K. Butt via teleconference. Due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, Contra Costa County and Governor Gavin Newsom issued multiple orders requiring sheltering in place, social distancing, and reduction of person-to-person contact. Accordingly, Governor Gavin Newsom issued executive orders that allowed cities to hold public meetings via teleconferencing (Executive Order N-29-20). DUE TO THE SHELTER IN PLACE ORDERS, attendance at the City of Richmond City Council meeting was limited to Councilmembers, essential City of Richmond staff, and members of the news media. Public comment was confined to items appearing on the agenda and was limited to the methods provided below. Consistent with Executive Order N-29-20, this meeting utilized teleconferencing only. The following provides information on how the public participated in the meeting. The public was able to view the meeting from home on KCRT Comcast Channel 28 or AT&T Uverse Channel 99 and livestream online at http://www.ci.richmond.ca.us/3178/KCRT- Live. Written public comments were received via email to [email protected]. Comments received by 1:00 p.m. on December 15, 2020, were summarized at the meeting, put into the record, and considered before Council action. Comments received via email after 1:00 p.m. and up until the public comment period on the relevant agenda item closed, were put into the record. Public comments were also received via teleconference during the meeting. -

Richmond Marina Bay Trail

↓ 2.1 mi to Point Richmond ▾ 580 Y ▾ A Must see, must do … Harbor Gate W ▶ Walk the timeline through the Rosie the Riveter Memorial to the water’s edge. RICHA centuryMO ago MarinaN BayD was Ma land ARIthat dissolvedNA into tidal marshBAY at the edge TRAIL SOUTH Shopping Center K H T R ▶ Visit all 8 historical interpretive markers and of the great estuary we call San Francisco Bay. One could find shell mounds left U R learn about the World War II Home Front. E A O G by the Huchiun tribe of native Ohlone and watch sailing vessels ply the bay with S A P T ▶ Fish at high tide with the locals (and remember Y T passengers and cargo. The arrival of Standard Oil and the Santa Fe Railroad at A your fishing license). A H A L L A V E . W B Y the beginning of the 20th century sparked a transformation of this landscape that continues ▶ Visit the S. S. Red Oak Victory ship in Shipyard #3 .26 mi M A R I N A W A Y Harbor Master A R L and see a ship’s restoration first hand. Call U today. The Marina Bay segment of the San Francisco Bay Trail offers us new opportunities B V O 510-237-2933 or visit www.ssredoakvictory.org. Future site of D to explore the history, wildlife, and scenery of Richmond’s dynamic southeastern shore. B 5 R Rosie the Riveter/ ESPLANADE DR. ▶ Be a bird watcher; bring binoculars. A .3 mi A WWII Home Front .37 mi H National Historical Park Visitor Center Marina Bay Park N Map Legend Sheridan Point I R ▶ MARINA BAY PARK was once at the heart Bay Trail suitable for walking, biking, 4 8 of Kaiser Richmond Shipyard #2. -

Cultural Resources Inventory Report For

CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY REPORT FOR PORTIONS OF THE RICHMOND PROPERTIES RICHMOND, CONTRA COSTA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA March 2013 PREPARED FOR: Tetra Tech, Inc. 1999 Harrison Street, Suite 500 Oakland, CA 94612 PREPARED BY: Barb Siskin, M.A., RPA Erica Schultz, M.H.P Kruger Frank, B.A. Garcia and Associates 1 Saunders Avenue San Anselmo, CA 94960 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY This report presents the results of the cultural resources investigation, which included the identification of archaeological resources and cultural landscape features, for portions of the University of California’s Richmond properties in Richmond, Contra Costa County, California. Within the 133-acre area comprised of these properties, the University of California proposes to consolidate the biosciences programs of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and to develop additional facilities for use by both the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and University of California, Berkeley, and other institutional or industry counterparts for research and development focused on energy, environment, and health. The Phase 1 development plan would construct the first three buildings within a smaller 16-acre area on these properties. Due to the involvement of the United States Department of Energy, the proposed Phase 1 development is a federal undertaking as defined by Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act and its implementing regulations, 36 Code of Federal Regulations Part 800. Therefore, only the smaller 16-acre area is subject to Section 106 regulations in order to take into account the effect of the undertaking on any historic property (i.e., district, site, building, structure, or object) that is included in or eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. -

Budget Justifications Are Prepared for the Interior, Environment and Related Agencies Appropriations Subcommittees

The United States BUDGET Department of the Interior JUSTIFICATIONS and Performance Information Fiscal Year 2016 NATURAL RESOURCE DAMAGE ASSESSMENT AND RESTORATION PROGRAM NOTICE: These budget justifications are prepared for the Interior, Environment and Related Agencies Appropriations Subcommittees. Approval for release of the justifications prior to their printing in the public record of the Subcommittee hearings may be obtained through the Office of Budget of the Department of the Interior. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fiscal Year 2016 Budget Justifications TABLE OF CONTENTS Appropriation: Natural Resource Damage Assessment and Restoration Summary of Request Page General Statement……..……….......................................................... 1 Executive Summary…………………………………………………. 2 Program Performance Summary ......................................................... 6 Goal Performance Table….................................................................. 8 Summary of Requirements Table....................................................... 10 Fixed Costs and Related Changes....................................................... 11 Appropriations Language.................................................................... 12 Program Activities Damage Assessments Activity............................................................ 15 Assessments and Restorations Site Map.......................................….. 20 Restoration Support Activity............................................................... 22 Inland Oil Spill Preparedness -

Tidal Marshes Are Either Exposed to the Open Bay Or Are Protected from Wave and Tidal Energy by Offshore Mudflats

Assessment Chapter Contra Costa County Adapting to Rising Tides Project Natural Shorelines Natural shorelines include a range of shoreline types and conditions. Fully tidal marshes are either exposed to the open Bay or are protected from wave and tidal energy by offshore mudflats. At the other end of spectrum are muted tidal marshes and ponds, that are protected from the Bay by berms and levees and have water levels controlled by tide gates and other structures. These systems provide an array of ecosystem service benefits, the loss of which will ultimately diminish the value of the Bay Area as a desirable place to live. Natural shorelines help reduce incoming wave heights, protecting shoreline structures from wind, waves, and tidal energy. Natural shorelines provide buffers to neighboring communities of all kinds, including disadvantaged and vulnerable communities, from sea level rise and storm surge. Their loss can place shoreline communities at greater risk of flooding by increasing the likelihood that structural shoreline protection is overtopped or fails, and can increase the cost of maintaining, repairing and upgrading these already expensive structural protection assets. In addition, many natural shorelines, including tidal and muted tidal marshes and ponds, have been restored and represent a significant financial investment. Many of these areas provide habitat to a number of state-listed or federally threatened and endangered species as well as migrating and wintering birds that rely on them for breeding, foraging, and high tide refuge. Additionally, they offer opportunities to view wildlife, provide access to the shoreline, and offer scenic and aesthetic benefits. Tidal Marshes Historically, tidal marshes keep pace with sea level rise by accumulating mineral sediment and by moving upward and landward in the tidal frame. -

Updated Draft Project List And

Examples of projects anticipated to be eligible for Restoration Authority grants. Last updated June 9, 2017 TOTAL LEAD (AND CURRENT PHASE PROJECT SCHEDULE CURRENT PROJECT COUNTY PROJECT DESCRIPTION PARTNER) SCHEDULE TOTAL COST LOCATION (Phase; dates or (Phase; dates PHASE COST ORGS years) or years) Peninsula and South Bay Phase 2 of the Yosemite Slough Restoration & Development Project will green and open a 21‐acre section of waterfront parkland in San Francisco's Candlestick Point California State Recreation Area that has remained closed to the Department of public since the park's inception in 1977, add 21 acres of Parks and restored waterfront parklands and recreational space in a Candlestick Recreation disadvantaged community, improve air and water quality, Peninsula and Point ‐ Yosemite San (State Parks), Planning and Construction: reduce and clean stormwater runoff, provide wildlife $1,300,000 $6,400,000 South Bay Slough Wetland Francisco California State Design: 2016‐2018 2018‐2019 habitat, and improve the ability of the park's natural Restoration Parks systems to buffer the impacts of climate change. The Foundation; San project will also provide valuable public access amenities Francisco Bay including a new 1,100 sq. ft. zero net energy Education Trail Center, 1.1 miles of new waterfront biking and pedestrian trails (including a section of the San Francisco Bay Trail), and ADA‐accessible park viewing and picnic/BBQ areas. Peninsula and South Bay Environmental education programs for students of all ages Golden Gate at the Crissy Field Center related to restoration projects. National Parks Crissy Field San The Center offers place‐based exploration that focuses on Conservancy, Educational ‐ ‐ ‐ ‐ Francisco the interaction between humans and nature and makes National Park Programs use of the natural and cultural resources of the restored Service, Presidio Crissy Field wetland and the Tennessee Hollow watershed. -

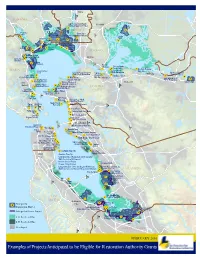

Examples of Projects Anticipated to Be Eligible for Restoration Authority Grants

Napa 221 |þ C a c h SONOMA e S lo u g Edgerly Island and South Fairfield h Wetlands Opportunity Area Rush Ranch NAPA Petaluma Lower Napa Marsh Skaggs Island Napa-Sonoma River Wetlands 80 Restoration ¨¦§ Suisun Lower Sonoma Marshes Marsh Creek Tolay Creek Strip Marsh Watershed Sears Point |þ37 Enhancements Bahia Tolay Creek Cullinan Wetlands Lagoon Ranch Lower Petaluma SOLANO er River iv R o Simmons Slough t r en e v m i Seasonal Wetlands Vallejo ra Novato Creek ac R S n i Baylands u q Bel Marin a o Keys Wetlands 780 J § Benicia n ¨¦ a Shoreline Pacheco Marsh S Restoration N Bay Point Regional e MARIN Lower Walnut w Y Lower Gallinas Shoreline ork Slou Creek Chelsea Wetlands & Lower Martinez Creek Restoration gh Big Break Regional Pinole Creek Restoration Pittsburg Shoreline-Oakley Lower Miller Regional McNabney Marsh Shoreline Creek/McInnis Marsh Point Pinole Martinez East Antioch Creek Creek to Bay Trash Regional Shoreline Marsh Restoration San Reduction Projects Breuner Marsh and Concord Dutch Slough Lower Rheem Creek Rafael Tiscornia Marsh 242 Restoration Project North Richmond Shoreline CONTRA |þ - San Pablo Marsh Lower Corte COSTA Madera Creek Point Molate, Lower Wildcat Richmond Creek Madera ¨¦§580 Bay Park Miller-Knoz, Richmond Western Stege Marsh Restoration Program Brooks Island Bothin Aramburu Point Isabel, Richmond Richmond 24 Marsh Island131 |þ |þ Albany Beach Richardson Berkeley North Strip Basin Bay Sausalito Berkeley Brickyard Eelgrass Preserve Point Emery Emeryville Crescent Oakland |þ13 Crissy Field Oakland Gateway Shoreline Educational Programs ¨¦§80 China Basin 680 Tennessee Alameda Point ¨¦§ Hollow Pier 70 - Crane Alameda Point Seaplane Lagoon Cove Park Lower Sausal Creek Pier 70 - Slipways Park Crown Beach – Neptune Point Islais Creek Warm Water Cove Park Pier 94- Wetlands Enhancement Martin Luther King Jr. -

SOE Layout 1 8/12/04 8:27 PM Page 1

SOE layout 1 8/12/04 8:27 PM Page 1 OPENING pursue diverse activities, including sor of the conference. CALFED is a REMARKS shipping, fishing, recreation, and cooperative state-federal effort, of commerce. Finally, the Estuary hosts which U.S. EPA is a part, to balance This Report describes the current a rich diversity of flora and fauna. efforts to provide water supplies and state of the San Francisco Bay- Two-thirds of the state's salmon and restore the ecosystem in the Bay- Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta nearly half the birds migrating along Delta watershed. Estuary's environment — waters, the Pacific Flyway pass through the wetlands, wildlife, watersheds, and Bay and Delta. Many government, the aquatic ecosystem. It also high- business, environmental, and com- TABLE lights new restoration research, munity interests now agree that bene- OF CONTENTS explores outstanding science ques- ficial use of the Estuary's resources tions, and offers take home notes for cannot be sustained without large- Executive Summary. 2 those working to protect California's scale environmental restoration. Keynote Address. 7 water supplies and endangered This 2004 State of the Estuary Vital Statistics . 9 species. Report summarizes restoration and San Francisco Bay and the Delta rehabilitation recommendations Pollutants . 27 combine to form the West Coast's drawn from the 43 presentations and Emerging largest estuary, where fresh water 129 posters of the October 2003 Pollutants . 35 from the Sacramento and San State of the Estuary Conference and Joaquin rivers and watersheds flows on related research. The report also Restoring the Estuary provides some vital statistics about out through the Bay and into the Watershed. -

Parks and Recreation Richmond General Plan 2030 Community Vision Richmond, California in 2030

10 Parks and Recreation Richmond General Plan 2030 Community Vision Richmond, California in 2030 Richmond’s parks, public plazas and open spaces create a strong sense of community identity, promote health and wellness, and protect historical and cultural amenities that are part of the City’s legacy. A variety of recreational programs and enrichment opportunities support the needs and interests of community members of all ages, incomes and abilities. Programs are acces- sible via public transit and pedestrian and bicycle routes that link schools and neighbor- hoods to program destinations. Richmond’s integrated system of parks provides public access to the San Pablo Peninsula, large-scale open spaces, neighborhoods, schools, urban parks, recreational facilities and other key destinations. Safe, park-like connections along restored creek channels, pedes- trian-friendly green streets and multi-use trails encourage walking and bicycling. Some parks, plazas and open spaces are located near civic and commercial areas. Each park in the City features distinctive components such as rich landscape elements and pub- lic art that respond to Richmond’s cultural values and history. Adults and children benefit from contact with nature in the urban context through unstructured natural play settings and walking paths. 10 Parks and Recreation Richmond residents recognize the importance spaces and community facilities linked together of high-quality parks and recreation facilities. via green multimodal corridors; Richmond’s parks, natural areas and recreational • Highlights key findings and recommendations programs are integral to creating a community that based on an existing conditions analysis; is socially and physically connected. Programs and • Defines goals for improving existing parks, strate- services provide valuable opportunities to engage gically expanding parklands and maximizing use and enrich residents and visitors alike.