SOE Layout 1 8/12/04 8:27 PM Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2011 510 520 3876

BPWA Walks Walks take place rain or shine and last 2-3 hours unless otherwise noted. They are free and Berkeley’s open to all. Walks are divided into four types: Theme Friendly Power Self Guided Questions about the walks? Contact Keith Skinner: [email protected] Vol. 14 No. 3 BerkeleyPaths Path Wanderers Association Fall 2011 510 520 3876. October 9, Sunday - 2nd An- BPWA Annual Meeting Oct. 20 nual Long Walk - 9 a.m. Leaders: Keith Skinner, Colleen Neff, To Feature Greenbelt Alliance — Sandy Friedland Sandy Friedland Can the Bay Area continue to gain way people live.” A graduate of Stanford Meeting Place: El Cerrito BART station, University, Matt worked for an envi- main entrance near Central population without sacrificing precious Transit: BART - Richmond line farmland, losing open space and harm- ronmental group in Sacramento before All day walk that includes portions of Al- ing the environment? The members of he joined Greenbelt. His responsibilities bany Hill, Pt. Isabel, Bay Trail, Albany Bulb, Greenbelt Alliance are doing everything include meeting with city council members East Shore Park, Aquatic Park, Sisterna they can to answer those questions with District, and Santa Fe Right-of-Way, ending a resounding “Yes.” Berkeley Path at North Berkeley BART. See further details Wanderers Asso- in the article on page 2. Be sure to bring a ciation is proud to water bottle and bag lunch. No dogs, please. feature Greenbelt October 22, Saturday - Bay Alliance at our Trail Exploration on New Landfill Annual Meeting Thursday, October Loop - 9:30 a.m. 20, at the Hillside Club (2286 Cedar Leaders: Sandra & Bruce Beyaert. -

Chapter 4.4 Cultural Resources

Section 4.4 Cultural Resources 4.4 CULTURAL RESOURCES 4.4.1 Introduction This section presents information on known and potentially existing cultural resources at the RBC site and analyzes the potential for development under the proposed 2014 LRDP to affect those resources. Information and analysis in this section is based on previous archaeological surveys (see Section 4.4.5) and those conducted for the current project: Cultural Resources Inventory Report for the Richmond Bay Campus, Alameda County (GANDA 2013) and Historic Properties Survey Report for Richmond Bay Campus (Tetra Tech 2013). Cultural resources can be prehistoric, Native American, or historic. Prehistoric resources are artifacts from human activities that predate written records; these are generally identified in isolated finds or sites. Prehistoric resources are typically archaeological and can include village sites, temporary camps, lithic scatters, roasting pits/hearths, milling features, petroglyphs, rock features, and burial plots. Historic resources are properties, structures, or built items from human activities that coincide with the epoch of written records. Historic resources can include archaeological remains and architectural structures. Historic archaeological sites include townsites, homesteads, agricultural or ranching features, mining-related features, refuse concentrations, and features or artifacts associated with early military and industrial land uses. Historic architectural resources can include houses, cabins, barns, lighthouses, other constructed buildings, and bridges. Generally, architectural resources that are over 50 years old are considered for evaluation for their historic significance. Public and agency NOP comments related to cultural resources are summarized below: For construction activities proposed in a state right-of-way, Caltrans requires that project environmental documentation include results of a current Northwest Information Center archaeological records search. -

Birding Northern California by Jean Richmond

BIRDING NORTHERN CALIFORNIA Site Guides to 72 of the Best Birding Spots by Jean Richmond Written for Mt. Diablo Audubon Society 1985 Dedicated to my husband, Rich Cover drawing by Harry Adamson Sketches by Marv Reif Graphics by dk graphics © 1985, 2008 Mt. Diablo Audubon Society All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part by any means without prior permission of MDAS. P.O. Box 53 Walnut Creek, California 94596 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . How To Use This Guide .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Birding Etiquette .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Terminology. Park Information .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 One Last Word. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Map Symbols Used. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Acknowledgements .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Map With Numerical Index To Guides .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 The Guides. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10 Where The Birds Are. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 158 Recommended References .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 165 Index Of Birding Locations. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 166 5 6 Birding Northern California This book is a guide to many birding areas in northern California, primarily within 100 miles of the San Francisco Bay Area and easily birded on a one-day outing. Also included are several favorite spots which local birders -

Weekly Projects Bidding 8/13/2021

Weekly Projects Bidding 8/13/2021 Reasonable care is given in gathering, compiling and furnishing the information contained herein which is obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but the Planroom is not responsible or liable for errors, omissions or inaccuracies. Plan# Name Bid Date & Time OPR# Location Estimate Project Type Monday, August 16, 2021 OUTREACH MEETING (VIRTUAL) EVERGREEN VALLEY COLLEGE (EVC) STUDENT SERVICES Addenda: 0 COMPLEX (REQUEST FOR SUB BIDS) SC 8/16/21 10:00 AM 21-02526 San Jose School ONLINE Plan Issuer: XL Construction 408-240-6000 408-240-6001 THIS IS A VIRTUAL OUTREACH MEETING. REGISTRATION IS REQUIRED. SEE FLYER FOR DETAILS. The 74,000 sf Student Services Complex at Evergreen Valley College is part of the San Jose Evergreen Community College District's Measure X Bond Program. This is a new ground-up two -story complex including collaboration spaces, offices, storage, restrooms and supporting facilities. All subcontractors must be prequalified with XL Construction to bid the project. Please email [email protected] for a prequalification application link, and [email protected] if you are an Under Utilized Business Enterprise (SBE, WBE, MBE, VBE...). REFINISHING GYM AND STAGE FLOORS AT CALIFORNIA SCHOOL FOR THE BLIND Addenda: 0 8/16/21 12:00 PM 21-02463 Fremont State-Federal Plan Issuer: California Department of Education - Personnel Service Division 916-319-0800 000-000-0000 Contract #: BF210152 The Contractor shall provide all labor, equipment and materials necessary for preparing and refinishing the stage and gym floors, twice a year, at the California School for the Blind (CSB), located at 500 Walnut Avenue, Fremont. -

San Francisco Bay Joint Venture

The San Francisco Bay Joint Venture Management Board Bay Area Audubon Council Bay Area Open Space Council Bay Conservation and Development Commission The Bay Institute The San Francisco Bay Joint Venture Bay Planning Coalition California State Coastal Conservancy Celebrating years of partnerships protecting wetlands and wildlife California Department of Fish and Game California Resources Agency 15 Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge Contra Costa Mosquito and Vector Control District Ducks Unlimited National Audubon Society National Fish and Wildlife Foundation NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Natural Resources Conservation Service Pacific Gas and Electric Company PRBO Conservation Science SF Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board San Francisco Estuary Partnership Save the Bay Sierra Club U.S. Army Corps of Engineers U.S. Environmental Protection Agency U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Geological Survey Wildlife Conservation Board 735B Center Boulevard, Fairfax, CA 94930 415-259-0334 www.sfbayjv.org www.yourwetlands.org The San Francisco Bay Area is breathtaking! As Chair of the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture, I would like to personally thank our partners It’s no wonder so many of us live here – 7.15 million of us, according to the 2010 census. Each one of us has our for their ongoing support of our critical mission and goals in honor of our 15 year anniversary. own mental image of “the Bay Area.” For some it may be the place where the Pacific Ocean flows beneath the This retrospective is a testament to the significant achievements we’ve made together. I look Golden Gate Bridge, for others it might be somewhere along the East Bay Regional Parks shoreline, or from one forward to the next 15 years of even bigger wins for wetland habitat. -

San Francisco Bay Plan

San Francisco Bay Plan San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission In memory of Senator J. Eugene McAteer, a leader in efforts to plan for the conservation of San Francisco Bay and the development of its shoreline. Photo Credits: Michael Bry: Inside front cover, facing Part I, facing Part II Richard Persoff: Facing Part III Rondal Partridge: Facing Part V, Inside back cover Mike Schweizer: Page 34 Port of Oakland: Page 11 Port of San Francisco: Page 68 Commission Staff: Facing Part IV, Page 59 Map Source: Tidal features, salt ponds, and other diked areas, derived from the EcoAtlas Version 1.0bc, 1996, San Francisco Estuary Institute. STATE OF CALIFORNIA GRAY DAVIS, Governor SAN FRANCISCO BAY CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION 50 CALIFORNIA STREET, SUITE 2600 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94111 PHONE: (415) 352-3600 January 2008 To the Citizens of the San Francisco Bay Region and Friends of San Francisco Bay Everywhere: The San Francisco Bay Plan was completed and adopted by the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission in 1968 and submitted to the California Legislature and Governor in January 1969. The Bay Plan was prepared by the Commission over a three-year period pursuant to the McAteer-Petris Act of 1965 which established the Commission as a temporary agency to prepare an enforceable plan to guide the future protection and use of San Francisco Bay and its shoreline. In 1969, the Legislature acted upon the Commission’s recommendations in the Bay Plan and revised the McAteer-Petris Act by designating the Commission as the agency responsible for maintaining and carrying out the provisions of the Act and the Bay Plan for the protection of the Bay and its great natural resources and the development of the Bay and shore- line to their highest potential with a minimum of Bay fill. -

Changes in Abundance and Distribution of Nesting Double-Crested Cormorants Phalacrocorax Auritus in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1975–2017

Rauzon et al.: Changes in nesting Double-Crested Cormorants in San Francisco Bay area 127 CHANGES IN ABUNDANCE AND DISTRIBUTION OF NESTING DOUBLE-CRESTED CORMORANTS PHALACROCORAX AURITUS IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA, 1975–2017 MARK J. RAUZON1*, MEREDITH L. ELLIOTT2, PHILLIP J. CAPITOLO3, L. MAX TARJAN4, GERARD J. McCHESNEY5, JOHN P. KELLY6 & HARRY R. CARTER7† 1Laney College, Geography Department, 900 Fallon Street, Oakland, CA 94607, USA *([email protected]) 2Point Blue Conservation Science, 3820 Cypress Drive, #11, Petaluma, CA 94954, USA 3Institute of Marine Sciences, University of California Santa Cruz, 115 McAllister Way, Santa Cruz, CA 95060, USA 4San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory, 524 Valley Way, Milpitas, CA 95035, USA 5US Fish and Wildlife Service, San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge Complex, 1 Marshlands Road, Fremont, CA 94555, USA 6Audubon Canyon Ranch, Cypress Grove Research Center, P.O. Box 808, Marshall, CA 94940, USA 7Humboldt State University, Department of Wildlife, 1 Harpst Street, Arcata, CA 95521, USA †Deceased Received 19 October 2018, accepted 13 February 2019 ABSTRACT RAUZON, M.J., ELLIOTT, M.L., CAPITOLO, P.J., TARJAN, L.M., McCHESNEY, G.J., KELLY, J.P. & CARTER, H.R. 2019. Changes in abundance and distribution of nesting Double-crested Cormorants Phalacrocorax auritus in the San Francisco Bay area, 1975–2017. Marine Ornithology 47: 127–138. In the San Francisco Bay area, California, the Double-crested Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus population has recovered from significant declines to reach breeding population sizes comparable to those from the late 19th century, when only one colony offshore at the South Farallon Islands (SFI) was known. -

Wildcat Creek Restoration Action Plan Version 1.3 April 26, 2010 Prepared by the URBAN CREEKS COUNCIL for the WILDCAT-SAN PABLO WATERSHED COUNCIL

wildcat creek restoration action plan version 1.3 April 26, 2010 prepared by THE URBAN CREEKS COUNCIL for the WILDCAT-SAN PABLO WATERSHED COUNCIL Adopted by the City of San Pablo on August 3, 2010 wildcat creek restoration action plan table of contents 1. INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 plan obJectives 5 1.2 scope 6 Urban Urban 1.5 Methods 8 1.5 Metadata c 10 reeks 2. WATERSHED OVERVIEW 12 c 2.1 introdUction o 12 U 2.2 watershed land Use ncil 13 2.3 iMpacts of Urbanized watersheds 17 april 2.4 hydrology 19 2.5 sediMent transport 22 2010 2.6 water qUality 24 2.7 habitat 26 2.8 flood ManageMent on lower wildcat creek 29 2.9 coMMUnity 32 3. PROJECT AREA ANALYSIS 37 3.1 overview 37 3.2 flooding 37 3.4 in-streaM conditions 51 3.5 sUMMer fish habitat 53 3.6 bioassessMent 57 4. RECOMMENDED ACTIONS 58 4.1 obJectives, findings and strategies 58 4.2 recoMMended actions according to strategy 61 4.3 streaM restoration recoMMendations by reach 69 4.4 recoMMended actions for phase one reaches 73 t 4.5 phase one flood daMage redUction reach 73 able of 4.6 recoMMended actions for watershed coUncil 74 c ontents version 1.3 april 26, 2010 2 wildcat creek restoration action plan Urban creeks coUncil april 2010 table of contents 3 figUre 1-1: wildcat watershed overview to Point Pinole Regional Shoreline wildcat watershed existing trail wildcat creek highway railroad city of san pablo planned trail other creek arterial road bart Parkway SAN PABLO Richmond BAY Avenue San Pablo Point UP RR San Pablo WEST COUNTY BNSF RR CITY OF LANDFILL NORTH SAN PABLO RICHMOND San Pablo -

REQUEST for QUALIFICATIONS and PROPOSALS Notice of Development Opportunity Historic Anitas Building: 920 Macdonald Ave

REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS AND PROPOSALS Notice of Development Opportunity Historic Anitas Building: 920 Macdonald Ave. Macdonald Ave. and 11th St. - 1940’s Source: Online Archive of California City of Richmond, California Issued by the City of Richmond, CA City Manager’s Office, Development Services Submission Deadline: May 3, 2019 at 12:00 PM (PDT) City of Richmond, CA REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS AND PROPOSALS Notice of Development Opportunity 920 Macdonald Ave. City of Richmond, California City Council Mayor Tom Butt Vice Mayor Melvin Willis Councilmember Nathaniel Bates Councilmember Ben Choi Councilmember Eduardo Martinez Councilmember Jael Myrick Councilmember Demnlus Johnson III City Manager Carlos Martinez City Manager Bill Lindsay Stay updated on all Richmond Opportunity Sites: http://www.ci.richmond.ca.us/OpportunitySites Request for Qualifications/Request for Proposals: 920 Macdonald Ave. 2 City of Richmond, CA Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................... 4 II. NEIGHBORHOOD & COMMUNITY ASSETS............................. 6 III. SITE VISION...................................................................................... 21 IV. SITE AND PARCEL SUMMARY...................................................... 23 V. DEVELOPMENT TEAM SELECTION............................................ 29 VI. SUBMITTAL REQUIREMENTS..................................................... 30 VII. SELECTION CRITERIA, PROCESS & SCHEDULE.................. 33 VIII. CITY NON-LIABILITY & RELATED MATTERS.................... -

Harbor Seal Annual Report 2005

Harbor Seal Monitoring at Point Reyes National Seashore and Golden Gate National Recreation Area Annual Report 2005 Prepared by: Melanie Vanderhoof and Sarah Allen 1 Introduction Harbor seals (Phoca vitulina richardii) are the dominant and only year round resident pinniped at Point Reyes, California. The Point Reyes seal population represents the largest concentration of harbor seals in the State of California, other than the Channel Islands, accounting for 20% of the mainland breeding population (Lowry and Carretta 2003). Much of the Point Reyes coastal zone remains fairly pristine and provides excellent marine and terrestrial habitat for seals to rest, molt feed and breed where human encroachment is minimal. Long-term monitoring studies of harbor seals have been conducted at selected colonies at Point Reyes since 1976 (Allen et al. 1989, Sydeman and Allen 1999, Allen et al. 2004). The objectives of monitoring are to 1) detect changes in population numbers, 2) detect changes in reproductive success and 3) identify anthropogenic or environmental factors that might affect population status and trends. The monitoring objectives and protocol are described in detail in Hester et al. (draft report). The information presented here is a summary of the data collected during the 2005 breeding and molting seasons, March- July. Summary data collected as part of a region-wide survey effort including adjacent areas (San Francisco Bay, San Mateo County and Sonoma County) where NPS surveys were conducted in 2005 in conjunction with other agencies and organizations are also presented. Methods Study Area The Point Reyes peninsula extends from Tomales Bay (Lat. 38° 30’N) south to Bolinas Lagoon (Lat. -

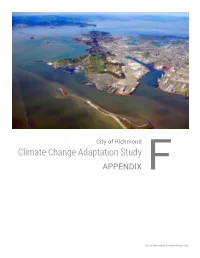

Climate Change Adaptation Study APPENDIX

City of Richmond Climate Change Adaptation Study APPENDIX City of Richmond Climate Action Plan Appendix F: Climate Change Adaptation Study Acknowledgements The City of Richmond has been an active participant in the Contra Costa County Adapting to Rising Tides Project, led by the Bay Conservation Development Commission (BCDC) in partnership with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the State Coastal Conservancy, the San Francisco Estuary Partnership, the San Francisco Estuary Institute, Alameda County Flood Control and Water Conservation District and the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, and consulting firm AECOM. Environmental Science Associates (ESA) completed this Adaptation Study in coordination with BCDC, relying in part on reports and maps developed for the Adapting to Rising Tides project to assess the City of Richmond’s vulnerabilities with respect to sea level rise and coastal flooding. City of Richmond Climate Action Plan F-i Appendix F: Climate Change Adaptation Study This page intentionally left blank F-ii City of Richmond Climate Action Plan Appendix F: Climate Change Adaptation Study Table of Contents Acknowledgements i 1. Executive Summary 1 1.1 Coastal Flooding 2 1.2 Water Supply 2 1.3 Critical Transportation Assets 3 1.4 Vulnerable Populations 3 1.5 Summary 3 2. Study Methodology 4 2.1 Scope and Organize 4 2.2 Assess 4 2.3 Define 4 2.4 Plan 5 2.5 Implement and Monitor 5 3. Setting 6 3.1 Statewide Climate Change Projections 6 3.2 Bay Area Region Climate Change Projections 7 3.3 Community Assets 8 3.4 Relevant Local Planning Initiatives 9 3.5 Relevant State and Regional Planning Initiatives 10 4. -

Hydrologic Investigation of Concrete Flood Control Channel at UC Berkeley’S Richmond Field Station

Hydrologic Investigation of Concrete Flood Control Channel at UC Berkeley’s Richmond Field Station by Patrick Nichols Abstract The Richmond Field Station Natural Restoration Project is a five year multimillion dollar effort. The first stages involve the remediation of polluted marsh lands, then the restoration of the upland prairie habitat, finishing with the adjacent channel. The concrete flood control channel is slated to become a free flowing creek and riparian corridor by the restoration planners at the university. The dynamics of this system must be understood to properly design a restoration, or creation plan since historically no creek existed there. This study assesses multiple aspects of the concrete channel to determine its health and qualifications for restoration. We calculated flow measurements at various intervals along the channel using velocity observations and the known cross sectional areas. We observed the depths creating a predictive relationship between depth and flow. Water quality characteristics: dissolved oxygen, turbidity, and conductivity were measured on a weekly basis for three months during the winter/spring of 2004. This information is used to help answer the question of what is the health of this system with regards to these variables, and what are its hydrological characteristics. Results show a consistent base flow of about 1 cubic foot per second with a peak flow around 152cfs. A linear relationship exists between depth and flow. The slope of the channel water surface is about 0.36%. The water quality parameters were indicative of a healthy system. The results of this project provide a base of knowledge for future investigation.