Social Science in Humanitarian Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malaba-Elegul/Nimule

Northern Corridor Stakeholders Survey September 2013 of Eldoret – Malaba – Elegu/Nimule – Juba Transit Section and South Sudan Consultative Mission The Permanent Secretariat of the Transit Transport Coordination Authority of the Northern Corridor P.O. Box 34068-80118 Mombasa-Kenya Tel: +254 414 470 735 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ttcanc.org Acknowledgements The Permanent Secretariat of the Transit Transport Coordination Authority of the Northern Corridor (NC-TTCA) would like to acknowledge all the public and private sector stakeholders for their contributions towards this survey. We thank the stakeholders consulted for their warm welcome, invaluable insights, information and time. Once again the Secretariat takes this opportunity to thank the Stakeholders who comprised the Survey Team namely; Kenya Revenue Authority, Kenya Ports Authority, Office de Gestion du Fret Multimodal DRC, Kenya National Police Service, South Sudan Chamber of Commerce, Uganda Private Sector Business Representative Mombasa, Kenya International Warehousing and Forwarders Association and the Kenya Transporters Association. Lastly we would like to appreciate the stakeholders who lent a helping hand to the Secretariat in organizing the meetings at the transit nodes during the survey. The Secretariat remains open to correct any errors of fact or interpretation in this document. i Glossary Acronyms: ASYCUDA Automated System for Customs Data C/Agent Customs Agent or Clearing Agent CBTA Cross Border Traders Association CIF Cost Insurance and Freight CFS Container -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Development of Inclusive Business Models (IBM) for Leveraging Investments and Development in Acholi Sub-Region

Development of Inclusive Business Models (IBM) for leveraging investments and development in Acholi sub-region Funded by: December 2017 Acknowledgements The authors of this report John Jagwe Ph.D. and Christopher Burke wish to express special thanks to Ms. Susan Toolit Alobo, Martina O’Donaghue and Ian Dolan of Trócaire for the support and feedback rendered in executing this assignment. The authors are also thankful to the respondents interviewed during the course of the research and to the Joint Acholi Sub- Regional Leaders Forum (JASLF) for the constructive inputs made to this work and the Democratic Governance Facility (DGF) for the support necessary to make this research and report possible. ii JASLF/Trócaire – Farmgain IBMs December 2017 Acknowledgement of Authors This report was authored by Dr. John Jagwe and Mr. Christopher Burke of Farmgain Africa Ltd for Trócaire Uganda as part of the overall research project on customary land practices in Acholi iii JASLF/Trócaire – Farmgain IBMs December 2017 Acronyms AAU Amatheon Agri Uganda ACE Area Co-operative Enterprises AVO Assistant Veterinary Officer BAT British America Tobacco DFID Department for International Development FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FCV Flue Cured Virgina ha Hectare HIV/AIDS Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome IBM Inclusive Business Model IFAD International Foundation for Agricultural Development IFC International Financial Co-operation Mt Metric tons NUAC Northern Uganda Agricultural Centre NUTEC Northern Uganda -

The Project for Community Development for Promoting Return and Resettlement of Idp in Northern Uganda

OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER AMURU DISTRICT/ NWOYA DISTRICT THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE PROJECT FOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FOR PROMOTING RETURN AND RESETTLEMENT OF IDP IN NORTHERN UGANDA FINAL REPORT MARCH 2011 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NTC INTERNATINAL CO., LTD. EID JR 11-048 Uganda Amuru Location Map of Amuru and Nwoya Districts Location Map of the Target Sites PHOTOs Urgent Pilot Project Amuru District: Multipurpose Hall Outside View Inside View Handing over Ceremony (December 21 2010) Amuru District: Water Supply System Installation of Solar Panel Water Storage facility (For solar powered submersible pump) (30,000lt water tank) i Amuru District: Staff house Staff House Local Dance Team at Handing over Ceremony (1 Block has 2 units) (October 27 2010) Pabbo Sub County: Public Hall Outside view of public hall Handing over Ceremony (December 14 2010) ii Pab Sub County: Staff house Staff House Outside View of Staff House (1 Block has 2 units) (4 Block) Pab Sub County: Water Supply System Installed Solar Panel and Pump House Training on the operation of the system Water Storage Facility Public Tap Stand (40,000lt water tank) (5 stands; 4tap per stand) iii Pilot Project Pilot Project in Pabbo Sub-County Type A model: Improvement of Technical School Project Joint inspection with District Engineer & Outside view of the Workshop District Education Officer Type B Model: Pukwany Village Improvement of Access Road Project River Crossing After the Project Before the Project (No crossing facilities) (Pipe Culver) Road Rehabilitation Before -

Northern Uganda Nutrition Survey in IDP Camps Gulu District, Northern

Northern Uganda Nutrition Survey in IDP Camps Gulu District, Northern Uganda Action Against Hunger (ACF-USA) June 2005 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACF-USA would like to acknowledge the help and support from the following people, without whom this survey would not have been conducted. Thanks to OFDA for their financial support in conducting the survey. Thanks to the District Department of Health Services (DDHS) for their agreement to let us conduct the survey and for their support of our activities within the District. Thanks to all the Camp Leaders, Zonal Leaders, and selected camp representatives who assisted us in the task of data collection. Thanks to the survey teams who worked diligently and professionally for many hours in the hot sun. Last and not least, thanks to the mothers and children, and their families who were kind enough to co- operate with the survey teams, answer personal questions and give up their time to assist us. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... 6 I.1 OBJECTIVES............................................................................................................................................. 6 I.2 RESULTS.................................................................................................................................................. 6 I.3 RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................................................................................................. -

The Charcoal Grey Market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan (2021)

COMMODITY REPORT BLACK GOLD The charcoal grey market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan SIMONE HAYSOM I MICHAEL McLAGGAN JULIUS KAKA I LUCY MODI I KEN OPALA MARCH 2021 BLACK GOLD The charcoal grey market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan ww Simone Haysom I Michael McLaggan Julius Kaka I Lucy Modi I Ken Opala March 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank everyone who gave their time to be interviewed for this study. They would like to extend particular thanks to Dr Catherine Nabukalu, at the University of Pennsylvania, and Bryan Adkins, at UNEP, for playing an invaluable role in correcting our misperceptions and deepening our analysis. We would also like to thank Nhial Tiitmamer, at the Sudd Institute, for providing us with additional interviews and information from South Sudan at short notice. Finally, we thank Alex Goodwin for excel- lent editing. Interviews were conducted in South Sudan, Uganda and Kenya between February 2020 and November 2020. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Simone Haysom is a senior analyst at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC), with expertise in urban development, corruption and organized crime, and over a decade of experience conducting qualitative fieldwork in challenging environments. She is currently an associate of the Oceanic Humanities for the Global South research project based at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Ken Opala is the GI-TOC analyst for Kenya. He previously worked at Nation Media Group as deputy investigative editor and as editor-in-chief at the Nairobi Law Monthly. He has won several journalistic awards in his career. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

LAND CONFLICT MONITORING and MAPPING TOOL for the Acholi Sub-Region

LAND CONFLICT MONITORING and MAPPING TOOL for the Acholi Sub-region Final Report - March 2013 Research conducted under the United Nations Peacebuilding Programme in Uganda by Human Rights Focus EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In a context of land disputes as a potential major conflict driver, the UN Peacebuilding Programme (PBP) commissioned Human Rights Focus (HURIFO) to develop a tool to monitor and map land disputes throughout Acholi. The overall purpose of this project is to obtain and analyse data that enhance understanding of land disputes, and through this to inform policy, advocacy, and other relevant interventions on land rights, security, and access in the sub-region. Two rounds of quantitative data collection have been undertaken comprehensively across the sub-region, in February/March and September/October 2012, along with further qualitative work and analysis of relevant literature. In order to maximise its contribution to urgently needed understanding of land disputes in Acholi, the project has sought to map and collect data not simply on the numbers and types of land disputes, but also on the substrata: the nature of the landholdings on which disputes are taking place; how land is used and controlled, and by whom. KEY FINDINGS • Over 90% of rural land is understood by the people who live there as under communal control/ownership. These communal land owners are variously understood as clans, sub-clans or extended families. • The overall number of discrete rural land disputes is declining significantly. Findings suggest that disputes are being resolved at a rate of about 50% over a six-month period. First-round research indicated that total land disputes between September/ October 2011 and February/March 2012 numbered about 4,300; second-round data identified just over 2,100 total disputes over the period between April and August/ September 2012. -

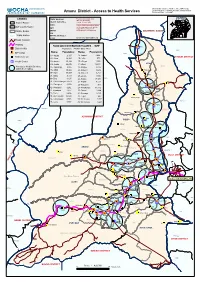

Amuru District - Access to Health Services Reference Date: June 2007

District, Sub counties, Heath centres,IDP Camps, Settlement sites, Tranpsort Network & Water bodies Amuru District - Access to Health Services Reference Date: June 2007 UGANDA LEGEND Data Sources Prepared and compiled by IMU OCHA-Uganda N District Border DDisatrticat SAuothuorrictiess Printed: 07 June 2006 _____________________________ W E AMURU NUDC The boundaries and names shown Sub County Border on this map approximate and do S WFP imply official endorsement/ Parish Border UNHCR acceptance by United Nations. SOUTHERN SUDAN IOM Kampala Water Bodies WHO/Health Cluster OCHA Email: [email protected] Road Network Railway FOOD AID DISTRIBUTION FIGURES - WFP Bibia [% District H/Qs Population: 288,062 (May 2007) PÆ OGILI Name: Population: Name: Population: IDP Camp DZAIPI Bibia 01- Agung 2,197 18- LanAgDoROl PI 3,422 Settlement site KITGUM DISTRICT 02- Alero 12,399 19- Lolim 573 PÆ Health Centre 03- Amuru 35,134 20- Olinga 1,565 ATIAK 04- Anaka 20,676 21- OlwaADl JUMAN TC 16,628 CIFORO Okidi Access to Health Services 05- Aparanga 2,955 22- Olwiyo 2,616 Pacilo within 5 km radius. 06- Atiak 19,980 23- Omee I 4,629 Abalokodi 07- Awer 14,997 24- Omee II 3,253 Pacilo 08- Bibia 5,133 25- Otong 1,572 09- Bira 3,105 26- Pabbo 47,173 PAKELLE Parwacha NOMANS 10- Corner Nwoya 5,279 27- Pagak 9,577 Okidi 11- Guruguru 3,360 Kal 28- Palukere 911 Atiak 12- Jeng-gari 4,292 29- Parabongo 13,672 PÆ OFUA 13- Kaladima 1,817 30- Pawel 3,884 Pupwonya 14- Keyo 6,606 31- Purongo 8,141 Palukere 15- Koch Goma 13,324 32- Tegot 442 Olamnyungo Palukere 16- Labongogali -

Northern Uganda

United Nations s/2006/29 Security Council Distr.: General 19 January 2006 Original: English Letter dated 16 January 2006 from the Charge d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Uganda to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council Reference is made to the letter dated 5 January 2006 from the Permanent Representative of Canada to the United Nations addressed to you (S/2006/13). On instructions from my Government, I have the honour to forward to you herewith a letter from the Minister for Foreign Affairs of Uganda transmitting an official position paper of the Government of Uganda on the humanitarian situation in northern Uganda (see annex). The Government of Uganda is giving a factual account of what is happening in northern Uganda and what the Government of Uganda is doing to address the situation on the ground. Any call for the situation in northern Uganda to be put on the agenda of the Security Council is therefore unjustified. I would be grateful if the present letter and its annex were circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Catherine Otiti Charge d’affaires a.i. 00-?1473 I: 240106 ,111 lllllll.ililII 111111 II Annex to the letter dated 16 January 2006 from the Charge d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Uganda to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council Attached is a synopsis of the humanitarian situation in northern Uganda (see appendix). It gives a historical background of the problem of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the ensuing humanitarian situation. -

Regional Economic Spillovers from the South Sudanese Civil War

Working paper Regional economic spillovers from the South Sudanese civil war Evidence from formal and informal cross border trade Jakob Rauschendorfer Ben Shepherd March 2020 Regional economic spillovers from the South Sudanese civil war: Evidence from formal and informal cross border trade Jakob Rauschendorfer and Ben Shepherd1 Abstract: This paper examines the impact of the South Sudanese civil war on trade in East Africa. In a first step, we employ a gravity model to examine the impact of civil conflict on the trade of neighbouring countries in a general sense and conduct a counterfactual simulation for the South Sudanese case. We show that an increase in the number of violent events to 2014 levels in 2012 (the last full pre-conflict year) would have reduced exports of neighbours to South Sudan by almost 9 percent. In a second step we conduct a case study for the impact of the conflict on Uganda. Here, we take advantage of unique survey data on informal cross-border trade as well as formal customs data and exploit the spatial and time variation of the conflict for causal identification. Our first result is that while the civil war had a sizeable negative impact on both formal and informal Ugandan exports the latter was hit much harder: Our preferred estimates suggest reductions of formal exports to South Sudan and Sudan by about 12 percent while informal exports to South Sudan were reduced by close to 80 percent compared to trade flows not exposed to the conflict. Converting these losses into monetary values, these figures suggest a reduction of Uganda’s total informal exports by a staggering 25 percent, while total formal exports were reduced by about two percent as a consequence of the conflict. -

Mother-Tongue Education (MTE) Project UGANDA Final Report

1 An Evaluation of the Literacy and Basic Education (LABE) Mother-Tongue Education (MTE) Project UGANDA Final Report Lead Evaluator: Kathleen Heugh Co-evaluator: Bwanika Mathias Mulumba LABE MTE Final Evaluation July – August 2013 2 Report Compiled by: Kathleen Heugh Research Centre for Languages and Cultures School of Communication, International Studies and Languages University of South Australia [email protected] With Bwanika Mathias Mulumba Department of Humanities & Language Education School of Education College of Education & External Studies Makerere University [email protected] 21 September 2013 LABE MTE Final Evaluation July – August 2013 3 Contents List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................................. 6 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 7 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 8 Key Achievements ............................................................................................................................... 9 Improved learner achievement in literacy and numeracy .............................................................. 9 Increased community and parental awareness of the value of local languages in education ....... 9 Increased capacity of language boards ........................................................................................