“Between Two Fires”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Project for Community Development for Promoting Return and Resettlement of Idp in Northern Uganda

OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER AMURU DISTRICT/ NWOYA DISTRICT THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE PROJECT FOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FOR PROMOTING RETURN AND RESETTLEMENT OF IDP IN NORTHERN UGANDA FINAL REPORT MARCH 2011 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NTC INTERNATINAL CO., LTD. EID JR 11-048 Uganda Amuru Location Map of Amuru and Nwoya Districts Location Map of the Target Sites PHOTOs Urgent Pilot Project Amuru District: Multipurpose Hall Outside View Inside View Handing over Ceremony (December 21 2010) Amuru District: Water Supply System Installation of Solar Panel Water Storage facility (For solar powered submersible pump) (30,000lt water tank) i Amuru District: Staff house Staff House Local Dance Team at Handing over Ceremony (1 Block has 2 units) (October 27 2010) Pabbo Sub County: Public Hall Outside view of public hall Handing over Ceremony (December 14 2010) ii Pab Sub County: Staff house Staff House Outside View of Staff House (1 Block has 2 units) (4 Block) Pab Sub County: Water Supply System Installed Solar Panel and Pump House Training on the operation of the system Water Storage Facility Public Tap Stand (40,000lt water tank) (5 stands; 4tap per stand) iii Pilot Project Pilot Project in Pabbo Sub-County Type A model: Improvement of Technical School Project Joint inspection with District Engineer & Outside view of the Workshop District Education Officer Type B Model: Pukwany Village Improvement of Access Road Project River Crossing After the Project Before the Project (No crossing facilities) (Pipe Culver) Road Rehabilitation Before -

Northern Uganda Nutrition Survey in IDP Camps Gulu District, Northern

Northern Uganda Nutrition Survey in IDP Camps Gulu District, Northern Uganda Action Against Hunger (ACF-USA) June 2005 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACF-USA would like to acknowledge the help and support from the following people, without whom this survey would not have been conducted. Thanks to OFDA for their financial support in conducting the survey. Thanks to the District Department of Health Services (DDHS) for their agreement to let us conduct the survey and for their support of our activities within the District. Thanks to all the Camp Leaders, Zonal Leaders, and selected camp representatives who assisted us in the task of data collection. Thanks to the survey teams who worked diligently and professionally for many hours in the hot sun. Last and not least, thanks to the mothers and children, and their families who were kind enough to co- operate with the survey teams, answer personal questions and give up their time to assist us. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... 6 I.1 OBJECTIVES............................................................................................................................................. 6 I.2 RESULTS.................................................................................................................................................. 6 I.3 RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................................................................................................. -

RUFORUM Monthly Newsletter

ISSN: 2073-9699RUFORUM MONTHLY VOLUME 3 ISSUE January 14 January,2010 2010 Page 1 RUFORUM MONTHLY The Monthly Brief of the Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture • RUFORUM Monthly is New leadership of Africa University pledge commit‐ an e-newsletter provid- ing information on ment to growth of Higher education in Africa activities of the Re- gional Universities The newly installed leadership of Africa University has pledged its continued commitment Forum for Capacity to the cause of higher education in Africa and has re‐dedicated itself to the successful Building in Agriculture. launch of the second phase of Africa University’s institutional development strategy. The • This Monthly Brief is third Chancellor and Vice Chancellor of Africa University, Bishop David Kekumba Yemba and circulated in the last Professor Fanuel Tagwira were both inaugurated at a colorful ceremony that took place at week of every month ■ the Africa University campus in Mutare, Zimbabwe on December 5, 2009. ANNOUNCEMENTS Over 500 dignitaries from around the world came to witness the historic event, which saw Inception planning meet‐ Zimbabwe government officials, members of the Africa University board of directors, part‐ ings for RUFORUM ACP S ner agencies of the United Methodist Church, partner institutions to Africa University and & T projects, Entebbe– Uganda 10‐12 February representatives from sister universities in Zimbabwe and within the region were present at 2010. the occasion. The last inauguration ceremony was held in December 1998, when the sec‐ International Conference ond Vice Chancellor of Africa University, Professor Rukudzo Murapa took office. on Agro‐Biotechnology, Biosafety and Seed Sys‐ “This installation signals tem in Developing Coun‐ tries: AGBIOSEED 2010. -

UGANDA COUNTRY READER TABLE of CONTENTS Stephen

UGANDA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Stephen Low 1957-1959 Deputy Chief of Mission, Kampala Hendri k Van Oss 1960-1962 Counsel General, Kampala Mi hael Pistor 1960-1961 Publi Affairs Assistant, US,S, Kampala Herman -. Cohen 1962-1963 Labor Atta h0, Kampala Hora e G. Dawson -r. 1962-1961 Cultural Affairs Offi er, US,A, Kampala Ol ott H. Deming 1962-1966 Ambassador, Uganda Miles 3edeman 1962-1968 Head of Capital Development and 6inan e, Afri a 7ureau, USA,D, 3ashington, DC 7eauveau 7. Nalle 1963-1966 Offi er-,n-Charge of Uganda Affairs, 3ashington, DC Samuel V. Smith 1965-1966 Pea e Corps Volunteer, Mbale 7eauveau 7. Nalle 1967-1970 Politi al Offi er, Kampala Roy Sta ey 1968-1969 Uganda Desk Offi er, USA,D, 3ashington, DC Vernon C. -ohnson 1970-1973 Mission Dire tor, USA,D, Kampala Arthur S. 7erger 1971-1972 Assistant Publi Affairs Offi er, Kampala Robert V. Keeley 1971-1973 Deputy Chief of Mission, Kampala Thomas P. Melady 1972-1973 Ambassador, Uganda Hariadene -ohnson 1977-1982 Offi e Dire tor for East Afri a, USA,D, 3ashington, DC Melissa 6oels h 3ells 1979-1982 United Nations Resident Representative, Uganda Gordon R. 7eyer 1980-1983 Ambassador, Uganda Allen C. Davis 1983-1985 Ambassador, Uganda ,rvin D. Coker 1983-1986 Mission Dire tor, USA,D, Kampala Greta N. Morris 1986-1988 Publi Affairs Offi er, US,S, Kampala Stephen Eisenbraun 1986-1988 Uganda Desk Offi er, State Department, 3ashington, DC Ri hard Podol 1986-1989 Mission Dire tor, USA,D, Kampala Robert E. Gribbin 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Kampala ,rvin D. -

Martin Aliker Invitational Lecture Makerere University Main Hall

Martin Aliker Invitational Lecture Makerere University Main Hall, August 2, 2012 Keynote Lecture The Role of Academia in Building a Sustainable Private Sector: the Case of Dr. Martin J. Aliker By Dr. William S. Kalema Salutations The Chancellor, Professor Mondo Kagonyera The Acting Vice-Chancellor Dr. and Mrs Martin Aliker Members of the Diplomatic Corps Chairman and Members of the University Council Academic Staff of Makerere University Students, Alumni, and other members of the Makerere community Distinguished guests Ladies and Gentlemen Distinguished guests, the organizers of this Seminar have asked to speak on the topic The role of the Academia in building a sustainable private sector : the case of Dr. Martin Aliker And even after I discussed the title of my talk with the organizers I was not entirely satisfied that I could do justice to it. Upon reflection, and with the permission of the organizers, I have chosen to rephrase the Title as 1 Dr. Martin J. Aliker : Profile of a Business Leader In my talk I will mention the qualities that make Martin an exemplar of good business leadership, and will talk about the influences and the personal traits that have enabled him to excel in the world of business. Martin is, indeed, a well-educated and cultured person; however, I will not infer that all, or even most, that is commendable about him is attributable to his excellent education. Of course, Martin has not only excelled in the business world; In 1960, Dr. Aliker became the first Ugandan to establish a private practice in dentistry and was, for many years, one of the most sought after dental surgeons in East Africa. -

LAND CONFLICT MONITORING and MAPPING TOOL for the Acholi Sub-Region

LAND CONFLICT MONITORING and MAPPING TOOL for the Acholi Sub-region Final Report - March 2013 Research conducted under the United Nations Peacebuilding Programme in Uganda by Human Rights Focus EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In a context of land disputes as a potential major conflict driver, the UN Peacebuilding Programme (PBP) commissioned Human Rights Focus (HURIFO) to develop a tool to monitor and map land disputes throughout Acholi. The overall purpose of this project is to obtain and analyse data that enhance understanding of land disputes, and through this to inform policy, advocacy, and other relevant interventions on land rights, security, and access in the sub-region. Two rounds of quantitative data collection have been undertaken comprehensively across the sub-region, in February/March and September/October 2012, along with further qualitative work and analysis of relevant literature. In order to maximise its contribution to urgently needed understanding of land disputes in Acholi, the project has sought to map and collect data not simply on the numbers and types of land disputes, but also on the substrata: the nature of the landholdings on which disputes are taking place; how land is used and controlled, and by whom. KEY FINDINGS • Over 90% of rural land is understood by the people who live there as under communal control/ownership. These communal land owners are variously understood as clans, sub-clans or extended families. • The overall number of discrete rural land disputes is declining significantly. Findings suggest that disputes are being resolved at a rate of about 50% over a six-month period. First-round research indicated that total land disputes between September/ October 2011 and February/March 2012 numbered about 4,300; second-round data identified just over 2,100 total disputes over the period between April and August/ September 2012. -

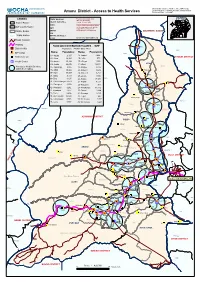

Amuru District - Access to Health Services Reference Date: June 2007

District, Sub counties, Heath centres,IDP Camps, Settlement sites, Tranpsort Network & Water bodies Amuru District - Access to Health Services Reference Date: June 2007 UGANDA LEGEND Data Sources Prepared and compiled by IMU OCHA-Uganda N District Border DDisatrticat SAuothuorrictiess Printed: 07 June 2006 _____________________________ W E AMURU NUDC The boundaries and names shown Sub County Border on this map approximate and do S WFP imply official endorsement/ Parish Border UNHCR acceptance by United Nations. SOUTHERN SUDAN IOM Kampala Water Bodies WHO/Health Cluster OCHA Email: [email protected] Road Network Railway FOOD AID DISTRIBUTION FIGURES - WFP Bibia [% District H/Qs Population: 288,062 (May 2007) PÆ OGILI Name: Population: Name: Population: IDP Camp DZAIPI Bibia 01- Agung 2,197 18- LanAgDoROl PI 3,422 Settlement site KITGUM DISTRICT 02- Alero 12,399 19- Lolim 573 PÆ Health Centre 03- Amuru 35,134 20- Olinga 1,565 ATIAK 04- Anaka 20,676 21- OlwaADl JUMAN TC 16,628 CIFORO Okidi Access to Health Services 05- Aparanga 2,955 22- Olwiyo 2,616 Pacilo within 5 km radius. 06- Atiak 19,980 23- Omee I 4,629 Abalokodi 07- Awer 14,997 24- Omee II 3,253 Pacilo 08- Bibia 5,133 25- Otong 1,572 09- Bira 3,105 26- Pabbo 47,173 PAKELLE Parwacha NOMANS 10- Corner Nwoya 5,279 27- Pagak 9,577 Okidi 11- Guruguru 3,360 Kal 28- Palukere 911 Atiak 12- Jeng-gari 4,292 29- Parabongo 13,672 PÆ OFUA 13- Kaladima 1,817 30- Pawel 3,884 Pupwonya 14- Keyo 6,606 31- Purongo 8,141 Palukere 15- Koch Goma 13,324 32- Tegot 442 Olamnyungo Palukere 16- Labongogali -

Northern Uganda

United Nations s/2006/29 Security Council Distr.: General 19 January 2006 Original: English Letter dated 16 January 2006 from the Charge d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Uganda to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council Reference is made to the letter dated 5 January 2006 from the Permanent Representative of Canada to the United Nations addressed to you (S/2006/13). On instructions from my Government, I have the honour to forward to you herewith a letter from the Minister for Foreign Affairs of Uganda transmitting an official position paper of the Government of Uganda on the humanitarian situation in northern Uganda (see annex). The Government of Uganda is giving a factual account of what is happening in northern Uganda and what the Government of Uganda is doing to address the situation on the ground. Any call for the situation in northern Uganda to be put on the agenda of the Security Council is therefore unjustified. I would be grateful if the present letter and its annex were circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Catherine Otiti Charge d’affaires a.i. 00-?1473 I: 240106 ,111 lllllll.ililII 111111 II Annex to the letter dated 16 January 2006 from the Charge d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Uganda to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council Attached is a synopsis of the humanitarian situation in northern Uganda (see appendix). It gives a historical background of the problem of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the ensuing humanitarian situation. -

Regional Development for Amuru and Nwoya Districts

PART 1: RURAL ROAD MASTER PLANNIN G IN AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS SECTION 2: REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FOR AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS Project for Rural Road Network Planning in Northern Uganda Final Report Vol.2: Main Report 3. PRESENT SITUATION OF AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS 3.1 Natural Conditions (1) Location Amuru and Nwoya Districts are located in northern Uganda. These districts are bordered by Sudan in the north and eight Ugandan Districts on the other sides (Gulu, Lamwo, Adjumani, Arua, Nebbi, Bulisa, Masindi and Oyam). (2) Land Area The total land area of Amuru and Nwoya Districts is about 9,022 sq. km which is 3.7 % of that of Uganda. It is relatively difficult for the local government to administer this vast area of the district. (3) Rivers The Albert Nile flows along the western border of these districts and the Victoria Nile flows along their southern borders as shown in Figure 3.1.2. Within Amuru and Nwoya Districts, there are six major rivers, namely the Unyama River, the Ayugi River, the Omee River, the Aswa River, Tangi River and the Ayago River. These rivers are major obstacles to movement of people and goods, especially during the rainy season. (4) Altitude The altitude ranges between 600 and 1,200 m above sea level. The altitude of the south- western area that is a part of Western Rift Valley is relatively low and ranges between 600 and 800 m above sea level. Many wild animals live near the Albert Nile in the western part of Amuru and Nwoya Districts and near the Victoria Nile in the southern part of Nwoya District because of a favourable climate. -

Social Science in Humanitarian Action

Social Science in Humanitarian Action www.socialscienceinaction.org Cross-border dynamics and healthcare in West Nile, Uganda Since the start of the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in August 2018, one single episode of Ebola has been reported within Uganda. A family travelled from Uganda to Mabalako Health Zone in North Kivu, DRC, to attend the funeral of their grandfather on 1 June 2019 (who was confirmed as having Ebola, on 2 June). They crossed back from DRC into Kasese District on 10 June, through the Bwera border post and sought medical care at Kagando hospital. The five-year-old grandson was symptomatic and, suspected of having Ebola, was transferred to Bwera Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU). The Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) confirmed that he had Ebola on 11 June, along with two other family members, his 50-year-old grandmother and three- year-old brother who were both also admitted to Bwera ETU. All three died. As of 26 June, 108 exposed contacts had been identified and were monitored daily. With no new cases or deaths reported, Uganda successfully completed its first 21-day follow-up period on 3 July 2019.1 On 30 June 2019, a case (mother of five children infected with Ebola, two of whom had already died) was confirmed in Ariwara Health Zone, Ituri Province, having travelled overland from Beni (460km south of Ariwara). This was the first confirmed case in this health zone. At the time of writing (5 July 2019), 177 family contacts had been listed, and 40 had already been vaccinated. -

UG-IDP-12 A3 07July09 Amuru District IDP Camps & Return Sites

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug AMURU DISTRICT: IDP Camps and Return Sites Population (May 2009) http://ochaonline.un.org Moyo e Uganda Overview Moyo Sudan SUDAN Congo (Dem. Rep) Bibia Kenya Adropi Dzaipi Kitgum Tanzania Rwanda Adjumani ATIAK Population by site Vilages 15904 Transit sites 3907 IDP Camps 11500 Returnees 19811 Oroko Atiak Pakelle Ciforo Palukere Adjumani Ofua Palaro Population by site Pawel Gulu Vilages 19457 Bira Transit sites 10343 Olinga IDP Camps 21604 Returnees 29800 Lugore Patiko- PABBO Otong Ajulu Pabbo Omee Awach Upper Jeng- Gari Population by site Vilages 29783 Cet Kana Lukodi Transit sites 4572 Population by site IDP Camps 13212 Parabongo Vilages 32842 Returnees 34355 AMURU Transit sites 8159 a IDP Camps 10897 LAMOGI Omee Returnees 41001 Coope Lower Mon Roc Awer Olwal Pagak Labongo- Kaladima Ogali Amuru Unyama Keyo Lacor Population by site Alokolum Vilages 15546 Langol Transit sites 12168 Te-tugu IDP Camps 1757 Koro- Returnees 12168 abili ALERO Alero Ongako Amuru Corner Nwoya Koch Palenga Goma Anaka Wii Anaka Bobi Tegot Wii ANAKA Lolim Anono Aparanga Population by site Purongo Olwiyo Vilages 12873 Awoo Transit sites 1449 IDP Camps 9348 Okwir Minakulu Nebbi Agung Returnees 14322 PURONGO KOCH GOMA Population by site Vilages 5819 Transit sites 1487 Population by site IDP Camps 4880 Vilages 18082 Returnees 7306 Transit sites 2046 IDP Camps 2792 Oyam Returnees 20128 Masindi AMURU DISTRICT Total Sub-counties 8 Parishes 51 Villages 114 IDP Camps 33 Return Sites 99 Villages 150,306 Popula Transit sites 44,131 tion in IDP Camps 75,990 Total Returnees 178,891 Data Sources: This map is a work in progress. -

Gulu District Landmine/ERW Victims Survey Report

Gulu District Landmine/ERW Victims Survey Report May 2006 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 SELECTED DEFINITIONS FROM IMAS GLOSSARY ---------------------------------------------- 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 7 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ------------------------------------------------------ 10 1.1 Presence of mines/ERW in Northern Uganda ------------------------------------ 10 1.2 Rationale and Objective of the research. ------------------------------------------ 11 2. RESEARCH METHODS AND OBSERVATIONS ------------------------------------------ 12 2.1 Study design and Population ---------------------------------------------------------- 12 2.2 Survey preparation and Training ----------------------------------------------------- 12 2.3 Sample size -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 12 2.4 Data collection --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 13 3. RESULTS AND FINDINGS ---------------------------------------------------------------------- 13 3.1 Study Profile ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 13 3.2 Demographic characteristics ---------------------------------------------------------