Influence of Green, Red and Blue Light Emitting Diodes On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transpiration

TRANSPIRATION BY: Dr. Madhu Gupta (Guest Faculty) SOS in Botany Jiwaji University Gwalior What is it? The loss of water in the vapour form from the exposed parts of a plant is called transpiration. The loss of water due to transpiration is quite high. Rather 98-99% of the water absorbed by a plant is lost in transpiration. Hardly 0.2% is used in photosynthesis while the remaining is retained in the plant during growth. Most of the transpiration occurs through foliar surface or surface of the leaves. It is known as foliar transpiration. Foliar transpiration accounts for over 90% of the total transpiration. Transpiration occurs through young or mature stem is called as Cauline transpiration. Depending upon the plant surface, transpiration is classified into three types: Stomatal • Water vapour diffuses out through minute pore (stomata) present in soft aerial part of plant is known Transpiration as Stomatal Transpiration • Sometimes water may evaporate through certain Lenticular other openings present on the older stems. These openings are called Lenticels and the transpiration Transpiration that takes place through term is known as Lenticular Transpiration. • Loss of water may also take place through cuticle, but Cuticular the amount so lost is relatively small • This type of transpiration depends upon the thickness Transpiration of the cuticle and presence or absence of wax coating on the surface of the leaves. Stomatal Transpiration Lenticular Transpiration Cuticular Transpiration Factors Affecting Transpiration: Water Stress: Whenever the rate of transpiration exceeds the rate of absorption, a water deficit is created in the plants and results in the incipient wilting of leaves. -

Photosynthesis Respiration and Transpiration.Notebook February 13, 2017

Photosynthesis Respiration and Transpiration.notebook February 13, 2017 Essential Question: What processes are required for plant survival? Key Concept: All living things need energy to carry out their basic functions. Living things break down food to get their energy.One thing that makes plants different from most others organisms is how they get their food. 1 Photosynthesis Respiration and Transpiration.notebook February 13, 2017 There are 3 processes that take place in the leaves that are mandatory for plant to survive. Photosynthesis Respiration Transpiration 2 Photosynthesis Respiration and Transpiration.notebook February 13, 2017 ALL PLANTS ARE AUTOTROPHS which means they make their own food for energy. Food for plants is SUGAR Remember: Chloroplast: Attract sunlight with chlorophyll Mitochondria: Energy Factory 3 Photosynthesis Respiration and Transpiration.notebook February 13, 2017 Observe the diagrams below. Can you infer which one is photosynthesis and respiration? 4 Photosynthesis Respiration and Transpiration.notebook February 13, 2017 What is needed: 1st Photosynthesis 1. Sunlight 2. Carbon Dioxide 3. Water What it Makes: Sugar (keeps) Oxygen (released for humans) Where it happens: Chloroplasts Sunlight Water H20 Carbon Dioxide CO2 Equation: Sunlight + 6H2O + 6CO2 = 6O2 + C6H12O6 5 Photosynthesis Respiration and Transpiration.notebook February 13, 2017 6 Photosynthesis Respiration and Transpiration.notebook February 13, 2017 Water Photosynthesis Sugar Carbon Oxygen Dioxide Excess Solar Energy Water 7 Photosynthesis Respiration and Transpiration.notebook February 13, 2017 Photosynthesis makes sugar, but in order to use the food the plant must break it down into usable energy through a process called Respiration. Food Respiration is the process of how plants break down the sugar so the plant can use it for energy. -

197 Section 9 Sunflower (Helianthus

SECTION 9 SUNFLOWER (HELIANTHUS ANNUUS L.) 1. Taxonomy of the Genus Helianthus, Natural Habitat and Origins of the Cultivated Sunflower A. Taxonomy of the genus Helianthus The sunflower belongs to the genus Helianthus in the Composite family (Asterales order), which includes species with very diverse morphologies (herbs, shrubs, lianas, etc.). The genus Helianthus belongs to the Heliantheae tribe. This includes approximately 50 species originating in North and Central America. The basis for the botanical classification of the genus Helianthus was proposed by Heiser et al. (1969) and refined subsequently using new phenological, cladistic and biosystematic methods, (Robinson, 1979; Anashchenko, 1974, 1979; Schilling and Heiser, 1981) or molecular markers (Sossey-Alaoui et al., 1998). This approach splits Helianthus into four sections: Helianthus, Agrestes, Ciliares and Atrorubens. This classification is set out in Table 1.18. Section Helianthus This section comprises 12 species, including H. annuus, the cultivated sunflower. These species, which are diploid (2n = 34), are interfertile and annual in almost all cases. For the majority, the natural distribution is central and western North America. They are generally well adapted to dry or even arid areas and sandy soils. The widespread H. annuus L. species includes (Heiser et al., 1969) plants cultivated for seed or fodder referred to as H. annuus var. macrocarpus (D.C), or cultivated for ornament (H. annuus subsp. annuus), and uncultivated wild and weedy plants (H. annuus subsp. lenticularis, H. annuus subsp. Texanus, etc.). Leaves of these species are usually alternate, ovoid and with a long petiole. Flower heads, or capitula, consist of tubular and ligulate florets, which may be deep purple, red or yellow. -

Summary a Plant Is an Integrated System Which: 1

Summary A plant is an integrated system which: 1. Obtains water and nutrients from the soil. 2. Transports them 3. Combines the H2O with CO2 to make sugar. 4. Exports sugar to where it’s needed Today, we’ll start to go over how this occurs Transport in Plants – Outline I.I. PlantPlant waterwater needsneeds II.II. TransportTransport ofof waterwater andand mineralsminerals A.A. FromFrom SoilSoil intointo RootsRoots B.B. FromFrom RootsRoots toto leavesleaves C.C. StomataStomata andand transpirationtranspiration WhyWhy dodo plantsplants needneed soso muchmuch water?water? TheThe importanceimportance ofof waterwater potential,potential, pressure,pressure, solutessolutes andand osmosisosmosis inin movingmoving water…water… Transport in Plants 1.1. AnimalsAnimals havehave circulatorycirculatory systems.systems. 2.2. VascularVascular plantsplants havehave oneone wayway systems.systems. Transport in Plants •• OneOne wayway systems:systems: plantsplants needneed aa lotlot moremore waterwater thanthan samesame sizedsized animals.animals. •• AA sunflowersunflower plantplant “drinks”“drinks” andand “perspires”“perspires” 1717 timestimes asas muchmuch asas aa human,human, perper unitunit ofof mass.mass. Transport of water and minerals in Plants WaterWater isis goodgood forfor plants:plants: 1.1. UsedUsed withwith CO2CO2 inin photosynthesisphotosynthesis toto makemake “food”.“food”. 2.2. TheThe “blood”“blood” ofof plantsplants –– circulationcirculation (used(used toto movemove stuffstuff around).around). 3.3. EvaporativeEvaporative coolingcooling. -

The Relationship Between Plant Growth and Water Consumption : a History from Greek Philosophers to Early 20Th Century Scientists

The relationship between plant growth and water consumption : A history from Greek philosophers to early 20th century scientists. Oliver Brendel Université de Lorraine, AgroParisTech, INRA, UMR SILVA Nancy, France email : [email protected] Tel : 00 33 383394100 postal address: Oliver Brendel, INRAE, UMR Silva, F-54280 CHAMPENOUX, France Abstract The relationship between plant growth and water consumption has for a long time occupied the minds of philosophers and natural scientists. The ratio between biomass accumulation and water consumption is known as water use efficiency and is widely relevant today in fields as diverse as crop improvement, forest ecology and climate change. Defined at scales varying from single leaf physiology to whole plants, it shows how botanical investigations changed through time, generally in tandem with developing disciplines and improving methods. The history started as a purely philosophical question by Greek philosophers of how plants grow, progressed through thought and actual experiments, towards an interest in plant functioning and their relationship to the environment. This article retraces this history by elucidating the progression of scientific questions posed through the centuries, presents the main methodological and conceptual developments. Keywords Transpiration efficiency; water use efficiency; plant physiology; botany Introduction The ratio of biomass accumulation per unit water consumption is known today as water use efficiency (WUE) and is widely relevant to agriculture ( e.g. Vadez et al.2014; Tallec et al.; Blum 2009), to forest ecology (e.g. Linares and Camarero 2012; Lévesque et al. 2014), and in the context of global climate change (e.g., Cernusak et al. 2019). This ratio can be defined at various levels, from the physiological functioning of a leaf to the whole plant and at the ecosystem level. -

Historical Review

1 Historical Review INTRODUCTION This chapter presents a brief historical review of progress in the field of plant water relations because the authors feel that it is impossible to fully understand the present without some knowledge of the past. As the Danish philosopher Kierkegaarde wrote, "Life can only be understood backward, but it can only be lived forward," and this also is true of science. The present generation needs to be reminded that some generally accepted concepts have their origin in ideas of 17th or 18th century writers and although others were suggested many decades ago, they were neglected until recently. As might be expected, the importance of water to plant growth was recog- nized by prehistoric farmers because irrigation systems already existed in Egypt, Babylonia (modern Iraq), and China at the beginning of recorded history, and the first European explorers found extensive irrigation systems in both North and South America. However, irrigation was not used extensively in agriculture in the United States until after the middle of the 19th century and little research on plant water relations occurred until the 20th century. Early Research Although plant water relations appear to have been the first area of plant physiology to be studied, progress was slow from Aristotle who died in 322 B.C. to the middle of the 19th century. According to Aristotle, plants absorbed their food ready for use from the soil, and plant nutrition was controlled by a soul or vital principle that ailowed plants to absorb only those substances useful in 2 1. Historical Review growth. This idea only began to be questioned in the 17th century by Jung, van Helmont, Mariotte, and others, and it ~ersistedinto the 19th century. -

Chapter 3 — Basic Botany

Chapter 3 BASIC BOTANY IDAHO MASTER GARDENER UNIVERSITY OF IDAHO EXTENSION Introduction 2 Plant Nomenclature and Classification 2 Family 3 Genus 3 Species 3 Variety and Cultivar 3 Plant Life Cycles 6 Annuals 6 Biennials 6 Perennials 6 Plant Parts and Their Functions 7 Vegetative Parts: Leaves, Stems, and Roots 7 Reproductive Parts: Flowers, Fruits, and Seeds 10 Plant Development 14 Seed Germination 14 Vegetative Growth Stage 14 Reproductive Growth Stage 14 Senescence 15 Further Reading and Resources 15 CHAPTER 3 BASIC BOTANY 3 - 1 Chapter 3 Basic Botany Jennifer Jensen, Extension Educator, Boundary County Susan Bell, Extension Educator, Ada County William Bohl, Extension Educator, Bingham County Stephen Love, Consumer Horticulture Specialist, Aberdeen Research and Extension Center Illustrations by Jennifer Jensen INTRODUCTION varying from country to country, region to region, and sometimes even within a local area. This makes Botany is the study of plants. To become a it difficult to communicate about a plant. For knowledgeable plant person, it is essential to example, the state flower of Idaho is Philadelphus understand basic plant science. It is important to lewisii , commonly called syringa in Idaho. In other understand how plants grow, how their various parts parts of the country, however, the same plant is function, how they are identified and named, and known as mock orange. To add to the confusion, how they interact with their environment. Learning Syringa is the genus for lilac shrubs. Another the language of botany means learning many new example of confusing common names is Malva words. Making the effort to learn this material will parviflora , which is called little mallow, round leaf prove extremely valuable and will create excitement mallow, cheeseweed, or sometimes buttonweed. -

Effect of Light Intensity and Leaf Temperature on Photosynthesis and Transpiration in Wheat and Sorghum

-----------,-~ " --._-----_.,--------- EFFECT OF LIGHT INTENSITY AND LEAF TEMPERATURE ON PHOTOSYNTHESIS AND TRANSPIRATION IN WHEAT AND SORGHUM By R. W. DOWNES* [Manuscript received March 18, 1970] Summary Wheat stomata offered less resistance to water and carbon dioxide diffusion than sorghum stomata at light intensities of 0·06 and 0·26 cal cm-2 min-i (400-700 nm) but resistances were comparable at 0·46 cal cm-2 min-i. Conse quently, transpiration rates were higher in wheat than in sorghum, except at the high light levels, in leaf chamber experiments described here. Rates of photo synthesis were higher in sorghum than in wheat, with the greatest difference at high light levels. This resulted in a greater efficiency of dry matter production relative to water use in sorghum. Transpiration rate increased with increased temperature in both species. Photosynthesis was independent of temperature in wheat, and in sorghum under low light conditions, but otherwise photosynthesis increased with temperature in sorghum. In both species, efficiency of water use decreased as temperature increased at all light intensities. Water vapour concentration difference between the intercellular spaces and the air was comparable in wheat and sorghum and increased with temperature. The carbon dioxide concentration difference between air and intercellular spaces was substantially greater in sorghum than in wheat and increased with leaf temperature. Maximum values were obtained at the intermediate light level in sorghum. I. INTRODUCTION Wheat plants were shown in earlier experiments to transpire at about 2·25 times the rate of sorghum plants per unit leaf area, under a range of temperatures (17-32°C) and low light intensities (1100-2800 f.c.) (Downes 1969). -

Reducing Transpiration to Conserve Water in Soil and Plants

major pathway of water loss from availability to the plant; and (2) conserves Reducing A plants is by transpiration, which ac- water in the plant itself, improving counts for 99 percent of the water taken growth by keeping water losses through transpiration to up by plant roots. This water is lost from the leaves in better balance with rate of the immediate area where the plant is uptake through the roots- i.e., the plant Consewe water in growing, since it passes via the atmos- is kept turgid. phere to some other point in the hydro- Plant growth depends basically on soil and plants logic cycle. Because the water that is two factors: (1) accumulating raw ma- transpired is essentially pure, salts in the terials for cell production, particularly soil water system become more concen- through photosynthesis, and (2) keeping trated. the plant turgid so cells can enlarge. The An antitranspirant (AT) applied to stomata1 pore lets in the carbon dioxide David C. Davenport transpiring plant surfaces to reduce needed for photosynthesis and allows Robert M. Hagan transpiration water losses (1) conserves water vapor to escape, influencing both Kay Uriu soil water in the root zone, extending its factors. An AT, which either plugs sto- Both pots of rugor beet were watered on the some day. Three days later, the unsprayed plant had exhausted Its sol1 molsture and wllted, whereas the plant prevlously sprayed wlth a fllm anMransplr ont stlll had sufflclent soil molsturo avallobie to prevent wlmng. 40~FORNlAAGRCULTURE.MAV1977 mata (“film forming”) or prevents com- ed for leaching. -

Ch. 36 Transport in Vascular Plants

Ch. 36 Transport in Vascular Plants Feb 41:32 PM 1 Essential Question: How does a tall tree get the water from its roots to the top of the tree? Feb 41:38 PM 2 Shoot architecture and Light Capture: Phyllotaxy arrangement of leaves on a stem to maximize light capture, reduce self shading determined by shoot apical meristem and specific to each species alternate = one leaf per node opposite = two leaves per node whorled = more than two leaves per node Norway spruce 1 is youngest leaf Apr 147:00 AM 3 leaf area index = ratio of total upper leaf surface of a single plant divided by surface area of land, normal value ~ 7 if above 7 leaves,branches undergo self pruning programmed cell death Mar 282:46 PM 4 Leaf orientations: horizontal leaf orientation for lowlight, capture sunlight more effectively vertical leaf orientation for high light, grasses, light rays coming in parallel to leaf so not too much light Apr 147:05 AM 5 Root architecture: mychorrhizae mutualistic relationship between fungi and roots 80% of land plants have this increases surface area for water and mineral absorption Mar 282:49 PM 6 Overview of transport in trees Feb 69:37 AM 7 Three types of transport in vascular plants: 1. transport of water and solutes by individual cells a. passive transport (osmosis) through aquaporins transport proteins water potential combined effects of solute concentration and physical pressure (esp. in plants due to cell wall) determines direction of movement of water free water moves high to low [ ] measured in megapascals (MPa) water potential = "0" in an open container (at sea level and rm. -

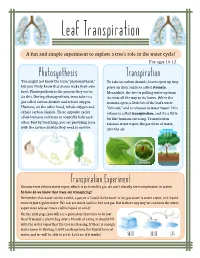

Leaf Transpiration

Leaf Transpiration A fun and simple experiment to explore a tree's role in the water cycle! For ages 10-12 Photosynthesis Transpiration You might not know the term "photosynthesis," To take in carbon dioxide, leaves open up tiny but you likely know that plants make their own pores on their surfaces called stomata. food. Photosynthesis is the process they use to Meanwhile, the tree is pulling water up from do this. During photosynthesis, trees take in a its roots all the way to its leaves. When the gas called carbon dioxide and release oxygen. stomata open, a little bit of the leaf's water Humans, on the other hand, inhale oxygen and "falls out," and is released as water vapor. This exhale carbon dioxide. These opposite cycles release is called transpiration, and it's a little allow humans and trees to naturally help each bit like humans sweating. Transpiration other. Just by breathing, you are providing trees releases water vapor, the gas form of water, with the carbon dioxide they need to survive. into the air. Transpiration Experiment Because trees release water vapor, which is an invisible gas, we can't directly see transpirationi n action. So how do we know that trees are transpiring? Remembert hat water can be a solid, a gas, or a liquid. Solid water is ice, gas water is water vapor, and liquid water is just regular water. We can see water and ice, but not gas. But is there any way we can turn the water vapor trees release into a visible liquid or solid? On the next page, you will see a procedure that tries to do just that! If we put a plastic bag over a branch of a tree, it should fill with the water vapor that the tree is releasing. -

Environmental Factors Influence Plant Vascular System and Water

plants Review Environmental Factors Influence Plant Vascular System and Water Regulation Mirwais M. Qaderi 1,2,* , Ashley B. Martel 2 and Sage L. Dixon 1 1 Department of Biology, Mount Saint Vincent University, 166 Bedford Highway, Halifax, NS B3M 2J6, Canada; [email protected] 2 Department of Biology, Saint Mary’s University, 923 Robie Street, Halifax, NS B3H 3C3, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 January 2019; Accepted: 11 March 2019; Published: 15 March 2019 Abstract: Developmental initiation of plant vascular tissue, including xylem and phloem, from the vascular cambium depends on environmental factors, such as temperature and precipitation. Proper formation of vascular tissue is critical for the transpiration stream, along with photosynthesis as a whole. While effects of individual environmental factors on the transpiration stream are well studied, interactive effects of multiple stress factors are underrepresented. As expected, climate change will result in plants experiencing multiple co-occurring environmental stress factors, which require further studies. Also, the effects of the main climate change components (carbon dioxide, temperature, and drought) on vascular cambium are not well understood. This review aims at synthesizing current knowledge regarding the effects of the main climate change components on the initiation and differentiation of vascular cambium, the transpiration stream, and photosynthesis. We predict that combined environmental factors will result in increased diameter and density of xylem vessels or tracheids in the absence of water stress. However, drought may decrease the density of xylem vessels or tracheids. All interactive combinations are expected to increase vascular cell wall thickness, and therefore increase carbon allocation to these tissues.