Joseph Deleon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queer. Nelson Sullivan (I)

Diarios sin piedad. Los ochenta: queer. Nelson Sullivan (I) Proyectamos en la sesión de hoy cuatro piezas, todas de 1989, que ofrecen Del Sur profundo a la efervescente Gran Manzana un primer acercamiento a su universo: Nelson Sullivan nació en una vieja familia de clase media-alta del Sur Monologue For TV Show (10 min). Nelson anda con su perro en uno de profundo de los Estados Unidos, en Kershaw, Carolina del Sur, en el sus paseos por la ciudad. Por primera y única vez se dirige a los hipotéticos año 1948. Después de graduarse en la universidad, se traslada a Nueva espectadores del primer capítulo del «Nelson TV Show», que nunca tendrá York a principios de los setenta con la idea de dedicarse a la música y a la secuela alguna. composición y con el deseo de huir de los prejuicios y de la claustrofobia propias de la vida en las pequeñas ciudades sureñas del país. Como tantos Nelson Goes to the Red Zone (29 min). Nelson ha sido invitado a una otros jóvenes homosexuales de su generación que emigraron hacia grandes discoteca con motivo de la presentación de una colección de moda, pero el centros urbanos, Nelson desea experimentar formas de vida más liberadas. portero, que no lo reconoce, le impide el paso. El mal humor de Nelson le Este fenómeno de éxodo se dio a conocer como «ola post-Stonewall», en vuelve chistoso y corrosivo. referencia a las violentas protestas que se produjeron, tras repetidas redadas policiales, en las calles de Nueva York en 1969 y que pasaron a la historia Gay Day Parade (26 min). -

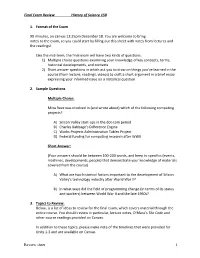

Final Exam Review History of Science 150

Final Exam Review History of Science 150 1. Format of the Exam 90 minutes, on canvas 12:25pm December 18. You are welcome to bring notes to the exam, so you could start by filling out this sheet with notes from lectures and the readings! Like the mid-term, the final exam will have two kinds of questions. 1) Multiple choice questions examining your knowledge of key concepts, terms, historical developments, and contexts 2) Short answer questions in which ask you to draw on things you’ve learned in the course (from lecture, readings, videos) to craft a short argument in a brief essay expressing your informed issue on a historical question 2. Sample Questions Multiple Choice: Mina Rees was involved in (and wrote about) which of the following computing projects? A) Silicon Valley start-ups in the dot-com period B) Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine C) Works Projects Administration Tables Project D) Federal funding for computing research after WWII Short Answer: (Your answers should be between 100-200 words, and keep to specifics (events, machines, developments, people) that demonstrate your knowledge of materials covered from the course) A) What are two historical factors important to the development of Silicon Valley’s technology industry after World War II? B) In what ways did the field of programming change (in terms of its status and workers) between World War II and the late 1960s? 3. Topics to Review: Below, is a list of ideas to review for the final exam, which covers material through the entire course. You should review in particular, lecture notes, O’Mara’s The Code and other course readings provided on Canvas. -

SCMS 2011 MEDIA CITIZENSHIP • Conference Program and Screening Synopses

SCMS 2011 MEDIA CITIZENSHIP • Conference Program and Screening Synopses The Ritz-Carlton, New Orleans • March 10–13, 2011 • SCMS 2011 Letter from the President Welcome to New Orleans and the fabulous Ritz-Carlton Hotel! On behalf of the Board of Directors, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to our members, professional staff, and volunteers who have put enormous time and energy into making this conference a reality. This is my final conference as SCMS President, a position I have held for the past four years. Prior to my presidency, I served two years as President-Elect, and before that, three years as Treasurer. As I look forward to my new role as Past-President, I have begun to reflect on my near decade-long involvement with the administration of the Society. Needless to say, these years have been challenging, inspiring, and expansive. We have traveled to and met in numerous cities, including Atlanta, London, Minneapolis, Vancouver, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. We celebrated our 50th anniversary as a scholarly association. We planned but unfortunately were unable to hold our 2009 conference at Josai University in Tokyo. We mourned the untimely death of our colleague and President-Elect Anne Friedberg while honoring her distinguished contributions to our field. We planned, developed, and launched our new website and have undertaken an ambitious and wide-ranging strategic planning process so as to better position SCMS to serve its members and our discipline today and in the future. At one of our first strategic planning sessions, Justin Wyatt, our gifted and hardworking consultant, asked me to explain to the Board why I had become involved with the work of the Society in the first place. -

THE WESTFIELD LEADER the Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newgpaper in Union County YEAR—No

THE WESTFIELD LEADER The Leading And Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newgpaper In Union County YEAR—No. 1 Entered a» Second Clans Matter Published Post Office. Westfleld. K. 1 WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 1956 Every Thursday 32 Page.—* CwU )elinquency Problem Is Registration For Adult Westfiety Public United Campaign jerious, Mayor Warns School Set For Monday School Enrollment Hits 6,000 Mark Children, Adults Registration night for the West- Goal Is $132,550 Responsibility Of field Adult School will be Monday Urged to Take from 7:30 to 9 p.m. in the cafe- Figures Reflect Salk Polio Series teria of the Roosevelt Junior High Increase of 537 You Have 2 More Parents Cited In School at 301 Clark street. Coun- Increase of 20 The Wwtfield Board of selors and instructors will be avail- Over Last Year Weeks to Register Heal tit today reminded resi- able to advise students in the se- Juvenile Control dent* th*t all re»trictio»« on ection of proper courses. Classes The largest enrollment in the There was a smart fellow Per Cent Over the use of privately purchased begin Oct. 1 and continue for ten history of the Westfield public called Morrie Tin seriousness of the juvenile polio vaccine have now be«n consecutive Monday nights ending schools was announced today by Who told his young brother i:»nuency problem was pointed removed. All age groups now Dec. 3. Superintendent of Schools Dr. S. named Lorrie: Last Year's Total today by Mayor H. Emerson are eligible to receive theae Booklets wen mailed out this N. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

A Field-Based Inquiry of Innovation Through Making and Craft

Handmade Future: A Field-based Inquiry of Innovation through Making and Craft Samantha Shorey A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Daniela K. Rosner, Chair Gina Neff, Chair Matthew Powers Christine Harold Megan Finn Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication © Copyright 2019 Samantha Shorey University of Washington Abstract Handmade Future: A Field-based Inquiry of Innovation through Making and Craft Samantha Shorey Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Gina Neff Department of Communication Daniela K. Rosner Department of Human Centered Design and Engineering This project analyzes the impact of mediated discourse on the skills, materials, and tools of innovation through a multi-method, three-part study of “making” practices— a growing method of Do-It-Yourself technology design that engages students, hobbyists, and experienced engineers in the building of technological artifacts outside of corporate hierarchies. Making integrates material skills (e.g. sewing, woodworking) and digital fabrication tools (e.g. 3D printing, laser cutting) to produce physical prototypes. These hybrid forms of construction hold significant promise as an inclusive method of innovation, acting as a pathway for women’s participation in technology design. However, if public conceptions of making neglect the contribution of craft and handwork, the potential for innovation will be reduced. This project contributes to existing scholarship in communication and science & technology (STS) studies by elucidating the mechanisms through which media produce symbolic value for technology industries and technology practices. Across this three-part project, I argue that when we expand popular narratives about the tools and practices of technology production, opportunities are also expanded to recognize the diverse contributions—both presently and historically—of people on the peripheries of STEM communities. -

My Path Through the FSM and Beyond Lee Felsenstein 22 Feb

1 My Path Through the FSM and Beyond Lee Felsenstein 22 Feb. 2005 © 2005 by Lee Felsenstein – all rights reserved This essay is a response to several requests for information on my particular political/technical trajectory from the FSM to the personal computer. “How did your involvement in the FSM affect your thinking on technology?” is one question from a PhD researcher, others ask about the overlap between the counterculture and the personal computer movement. This is a part of a future, more comprehensive memoir. The Environment In 1963, when I entered the College of Engineering at Berkeley as a freshman, the world was a much different place from today, especially for an 18-year-old acolyte entering the priesthood of technology. Engineers and other technologists were almost universally participants in large commercial or military institutions (or both – the “military industrial complex” described by Eisenhower in his farewell address). You worked as a small cog within a massive structure, with paper, pencil and slide rule as your principal tools. Numerous file clerks, documentation clerks, secretaries and technicians provided supporting services. If you needed computer time you had to write a justification and then write your program on coding sheets, one letter or number to a square. Someone else keypunched the code and had the resulting deck of cards delivered to a remote computer. You got back a batch of printout over which you pored until you decided whether the results were correct or whether another cycle would necessary. The upshot was that in your vocation you disappeared into a vast technological machine which was visible to the general public through its products – the space program, pharmaceuticals, automobiles and aircraft. -

Artist and Entrepreneur

Artist and Entrepreneur Identifying and developing key qualifications pertaining cultural entrepreneurship for musical acts Eskil Immanuel Holm Jessen Master thesis at the Institute of Musicology UNIVERSITY OF OSLO May 2018 II Foreword I would like to thank my supervisor Per Ole Hagen for all his encouragement, inspiration and initiative, without which I would have been in a sorry state. I would like to thank my respondents for their participation, without which this thesis would never have seen the light of day. They have been eager to share of their knowledge of the music industries and their thoughts and perspectives regarding artists they work with, I will be forever grateful to them. A great deal of gratitude is sent in the direction of my good friend Milad Amouzegar, who has been a great team player through this entire endeavor, I thank you for all our long nights and early mornings of writing, proofreading and discussing our theses. To all my friends and family whom has been unrelenting in their belief and support these last two years, my deepest and most sincere thanks, you are all a part of this. Lastly, I would like to thank the institute of musicology for the opportunity to realize this thesis and especially Associate Professor Kyle Devine who made me realize just how exiting musicology can be at its best. Oslo, May 1st 2018 Eskil Immanuel Holm Jessen III IV Identifying and developing key qualifications pertaining cultural entrepreneurship for musical acts Eskil Immanuel H. Jessen Institute of Musicology V Copyright Eskil Immanuel H. Jessen 2018 Artist and Entrepreneur: Identifying and developing key qualifications pertaining cultural entrepreneurship for musical acts Eskil Immanuel H. -

And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

A SPACE FOR CONNECTION: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL INQUIRY ON MUSIC LISTENING AS LEISURE by JOSEPH ALFRED PATE IV (Under the Direction of Corey W. Johnson) ABSTRACT This polyvocal text leveraged Post-Intentional Phenomenology (Vagle, 2010) to trouble, open up, and complexify understanding of the lived leisure experience (Parry & Johnson, 2006) of connection with and through music listening. Music listening was foregrounded as one horizon within the aural soundscape that affords deeply meaningful and significant experiences for many. Past scholarship within the Leisure Studies literature has primarily attended to the impact and relevancy of music in the lives of adolescents. This study focused on engagement with music of five adults, accessing phenomenology as both a philosophical and methodological lens to look along (Lewis, 1990) this lived-experience. Using multiple voices and styles of representation, this polyvocal work challenged traditional ways of knowing by inviting listening, music, and voice to serve as additional data embedded throughout its discursive representation. Accessing Bachelard‟s (1990) phenomenology of the resonation-reverberation doublet revealed five partial, fleeting, and tentative manifestations (Vagle, 2010) of this lived leisure experience, which included: Getting Lost: Felt Resonation and Embodiment; I‟m Open: Openness, Receptivity, and Enchantment; Serendipitous Moments; The Found Mirror: Oh There You Are; and Cairns and Echoes: The Lustering Potency of Song. Ultimately, music appeared to speak to so as to speak for participants, providing musical affirmation and sustenance throughout their lives. INDEX WORDS: Music, Listening, Leisure, Post-Intentional Phenomenology, Polyvocal Text A SPACE FOR CONNECTION: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL INQUIRY ON MUSIC LISTENING AS LEISURE by JOSEPH ALFRED PATE IV B. -

Fort Gansevoort

FORT GANSEVOORT A Look Back: 50 Years After Stonewall Opening On: Thursday, July 11, 6 – 8 PM July 11 – August 10, 2019 Fort Gansevoort presents A Look Back: 50 Years After Stonewall, organized by Lucy Beni and Adam Shopkorn. The exhibition commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, a six-day riot said to have been spontaneously set off by Marsha P. Johnson in protest of one of many regular police raids at The Stonewall Inn, a gay bar located in New York City’s Greenwich Village. This event marks the beginning of the Gay Liberation movement and the contemporary fight for LGBTQ+ rights in the United States. A Look Back: 50 Years After Stonewall unites the work of queer artists living and producing in and around New York City beginning around the time of the Stonewall Uprising in 1969 and leading into the 1980s. This is only a portion of the story, an incomplete history, most especially given that the Gay Liberation movement and its coinciding contemporary art market had not placed transgender voices nor people of color at the forefront of the conversation. The exhibition includes both documentation of the Gay Liberation movement and a look back at the work made by LGBTQ+ artists during this time. Central to the work included are the subjects of protest, revolt, celebration, and love. Kate Millett’s sculpture, American Flag Goes to Pot (1970) provides a blunt protest to government authority, while Joan E. Biren’s photograph’s document the tenderness of love between two women. The work made during the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, beginning in 1981, becomes entangled in death and remembrance, an epidemic defining this decade most especially in the New York City queer community and resulting in a tremendous amount of loss. -

San Francisco Pride Announces Additional Entertainment and Special Guests for Official Pride 50 Online Celebration

Media Contacts: Julie Richter | [email protected] Peter Lawrence Kane | [email protected] SAN FRANCISCO PRIDE ANNOUNCES ADDITIONAL ENTERTAINMENT AND SPECIAL GUESTS FOR OFFICIAL PRIDE 50 ONLINE CELEBRATION JUNE 27–28, 2020 SAN FRANCISCO (June 18, 2020) — Today, the Board of Directors of San Francisco Pride announced additional entertainment and special Guests participatinG in the official Pride 50 online celebration takinG place Saturday, June 27 and Sunday, June 28, 2020. To celebrate the milestone anniversary, San Francisco leGendary draG icons Heklina, Honey Mahogany, Landa Lakes, Madd Dogg 20/20, Peaches Christ, and Sister Roma will come toGether for Decades of Drag, a conversation where they reflect on decades of activism, struGGles, and victories. JoininG the previously announced artists, the tribute to LGBTQ+ luminaries and Queer solidarity includes performances by Madame Gandhi, VINCINT, Elena Rose, Krystle Warren, La Doña, and LadyRyan, presented by SF Queer NiGhtlife. The weekend proGram also features a spotliGht on Openhouse and the livinG leGacy of Black Queer and transgender activism; National Center for Lesbian RiGhts Exeutive Director Imani Rupert-Gordon discussinG Black Lives Justice; and a deep dive into the history of the LGBTQ+ community in music with Kim Petras. Additional special appearances include Bay Area American Indian TwoSpirits, body positive warrior Harnaam Kaur, AlPhabet Rockers, Cheer SF (celebratinG forty years!), a conversation on the intersection of Black and Gay issues between Dear White People creator Justin Simien and cast member Griffin Matthews, and best-of performances from San Francisco’s oldest Queer bar The Stud. Previously announced entertainment includes hosts Honey Mahogany, Per Sia, Sister Roma, and Yves Saint Croissant, as well as New Orleans-born Queen of Bounce, Big Freedia as the Saturday headliner. -

Answer Key: Parallel Structure—Exercise A

Sheldon Lawrence, Ph.D. ©2014 www.stillwaterspress.com [email protected] Available at Amazon.com Table of Contents Meet the Sentence �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������01 Building a Sentence ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������11 Fragments ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������16 Run-on Sentences ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������23 Commas ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������28 Confused Words �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������45 Commonly Misspelled Words ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������56 Shifts in Time �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������62 Parallel Structure ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������66 Problems with Pronouns �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������76 Capitalization�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������86