My Path Through the FSM and Beyond Lee Felsenstein 22 Feb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

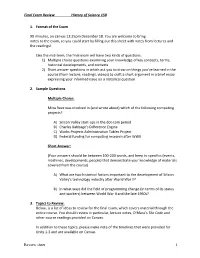

Final Exam Review History of Science 150

Final Exam Review History of Science 150 1. Format of the Exam 90 minutes, on canvas 12:25pm December 18. You are welcome to bring notes to the exam, so you could start by filling out this sheet with notes from lectures and the readings! Like the mid-term, the final exam will have two kinds of questions. 1) Multiple choice questions examining your knowledge of key concepts, terms, historical developments, and contexts 2) Short answer questions in which ask you to draw on things you’ve learned in the course (from lecture, readings, videos) to craft a short argument in a brief essay expressing your informed issue on a historical question 2. Sample Questions Multiple Choice: Mina Rees was involved in (and wrote about) which of the following computing projects? A) Silicon Valley start-ups in the dot-com period B) Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine C) Works Projects Administration Tables Project D) Federal funding for computing research after WWII Short Answer: (Your answers should be between 100-200 words, and keep to specifics (events, machines, developments, people) that demonstrate your knowledge of materials covered from the course) A) What are two historical factors important to the development of Silicon Valley’s technology industry after World War II? B) In what ways did the field of programming change (in terms of its status and workers) between World War II and the late 1960s? 3. Topics to Review: Below, is a list of ideas to review for the final exam, which covers material through the entire course. You should review in particular, lecture notes, O’Mara’s The Code and other course readings provided on Canvas. -

A History of the Personal Computer Index/11

A History of the Personal Computer 6100 CPU. See Intersil Index 6501 and 6502 microprocessor. See MOS Legend: Chap.#/Page# of Chap. 6502 BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. Languages -- Numerals -- 7000 copier. See Xerox/Misc. 3 E-Z Pieces software, 13/20 8000 microprocessors. See 3-Plus-1 software. See Intel/Microprocessors Commodore 8010 “Star” Information 3Com Corporation, 12/15, System. See Xerox/Comp. 12/27, 16/17, 17/18, 17/20 8080 and 8086 BASIC. See 3M company, 17/5, 17/22 Microsoft/Prog. Languages 3P+S board. See Processor 8514/A standard, 20/6 Technology 9700 laser printing system. 4K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. See Xerox/Misc. Languages 16032 and 32032 micro/p. See 4th Dimension. See ACI National Semiconductor 8/16 magazine, 18/5 65802 and 65816 micro/p. See 8/16-Central, 18/5 Western Design Center 8K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. 68000 series of micro/p. See Languages Motorola 20SC hard drive. See Apple 80000 series of micro/p. See Computer/Accessories Intel/Microprocessors 64 computer. See Commodore 88000 micro/p. See Motorola 80 Microcomputing magazine, 18/4 --A-- 80-103A modem. See Hayes A Programming lang. See APL 86-DOS. See Seattle Computer A+ magazine, 18/5 128EX/2 computer. See Video A.P.P.L.E. (Apple Pugetsound Technology Program Library Exchange) 386i personal computer. See user group, 18/4, 19/17 Sun Microsystems Call-A.P.P.L.E. magazine, 432 microprocessor. See 18/4 Intel/Microprocessors A2-Central newsletter, 18/5 603/4 Electronic Multiplier. Abacus magazine, 18/8 See IBM/Computer (mainframe) ABC (Atanasoff-Berry 660 computer. -

COMMUNITY MEMORY Wants to Change That

Mass communications media tell everybody what a few people have to Community say, and don't give you a chance to talk back, much less talk to each other. Memory COMMUNITY MEMORY wants to change that. We are placing public computer terminals through which • Read and Add Messages people can freely share information • Make a connection unmediated by censors. • Share your ideas Community Memory allows people with no previous computer experience to enter messages, find messages entered by others, and enter responses to what they see. Messages are cross-indexed to related subjects to help people make connections. Community Memory helps people get in touch with one another. You can use it to find housing, childcare, or people to play Softball with. It is also a forum for expressing your views on subjects ranging from local politics to science fiction. The Community Memory Project is a non-profit corporation interested in the social impacts of computer technology. We have been in existence since 1976, and have been operating a small prototype of Community Memory in Berkeley with five terminals since 1984. recyling centers! The Community Memory Project is happy to announce that we are expanding. We will be adding a number For more information or to subscribe to our of new terminals and new features to newsletter call (415) 841-1114 or write us at: the existing system. We welcome your ideas concerning this expansion. How The Community Memory Project could the system best meet your 2617 San Pablo Ave. needs? What are the best locations for Berkeley, CA 94702 terminals in your community? WHAT IS COMMUNITY MEMORY? This computer terminal is part of the COMMUNITY MEMORY system. -

Joseph Deleon

Social Media at the Margins: Crafting Community Media Before the Web by Joseph Richard DeLeon A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Film, Television, and Media) in the University of Michigan 2021 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Daniel Herbert, Co-Chair Associate Professor Sheila Murphy, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Sarah Murray Professor Lisa Nakamura Joseph Richard DeLeon [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1662-9033 © Joseph Richard DeLeon 2021 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Carol DeLeon and Richard DeLeon. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation is the result of the community and support that shaped my doctoral education in so many important and life-changing ways. I have had the incomparable joy to benefit from great mentors who have fostered my intellectual growth from my first steps on campus all the way to my dissertation defense. To my co-chairs, Dan Herbert and Sheila Murphy, thank you for guiding me through this project and for helping me to harness the strengths of my research, my perspective, and my voice. Thank you to Dan, who has always offered a helpful listening ear and shared a wealth of advice from choosing seminars, to networking, publishing, and finishing a dissertation. Thank you to Sheila for your constant support and encouragement of my writing, my teaching, and my curiosity. I thank Sheila for the many conversations that spurred my writing in new and fruitful directions and that made me feel valued as a scholar and as an individual. I am especially grateful for Sheila’s advice for my research trips to Silicon Valley and for encouraging me to witness Fry’s Electronics firsthand. -

Wizards, Bureaucrats, Warriors, and Hackers: Writing the History of the Internet Author(S): Roy Rosenzweig Source: the American Historical Review, Vol

Wizards, Bureaucrats, Warriors, and Hackers: Writing the History of the Internet Author(s): Roy Rosenzweig Source: The American Historical Review, Vol. 103, No. 5, (Dec., 1998), pp. 1530-1552 Published by: American Historical Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2649970 Accessed: 31/07/2008 15:02 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aha. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Review Essay Wizards, Bureaucrats, Warriors, and Hackers: Writing the History of the Internet ROY ROSENZWEIG TAKE A LOOK AT THE STANDARD TEXTBOOKS on post-World War II America. -

Lee Felsenstein Papers M1443

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c89k4hmz No online items Guide to the Lee Felsenstein Papers M1443 Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2018 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Lee Felsenstein M1443 1 Papers M1443 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Lee Felsenstein papers creator: Felsenstein, Lee. Identifier/Call Number: M1443 Physical Description: 56 Linear Feet Date (inclusive): circa 1975-2007 Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The papers of computer designer Lee Felsenstein contain material about the development of personal computers through the 1970s and 80s. Biographical / Historical Lee Felsenstein is an electronic design engineer known for his contributions to the early history of personal computing. Born in Philadelphia, PA in 1945, Felsenstein studied electrical engineering and computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, where he took part in the 1964 Free Speech Movement protests and was employed as a junior engineer at Ampex. Working as a contract engineer since the 1970’s, much of Felsenstein’s output has focused on making personal computing more publicly accessible. His contributions to the history of computing include designing the 1973 Pennywhistle modem, an early acoustic coupler modem affordable to hobbyists, -

The Virtual Community Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier

The Virtual Community Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier by Howard Rheingold ADDISON-WESLEY PUBLISHING COMPANY Reading, MA Copyright © 1993 by Howard Rheingold "When you think of a title for a book, you are forced to think of something short and evocative, like, well, 'The Virtual Community,' even though a more accurate title might be: 'People who use computers to communicate, form friendships that sometimes form the basis of communities, but you have to be careful to not mistake the tool for the task and think that just writing words on a screen is the same thing as real community.'" – HLR We know the rules of community; we know the healing effect of community in terms of individual lives. If we could somehow find a way across the bridge of our knowledge, would not these same rules have a healing effect upon our world? We human beings have often been referred to as social animals. But we are not yet community creatures. We are impelled to relate with each other for our survival. But we do not yet relate with the inclusivity, realism, self-awareness, vulnerability, commitment, openness, freedom, equality, and love of genuine community. It is clearly no longer enough to be simply social animals, babbling together at cocktail parties and brawling with each other in business and over boundaries. It is our task--our essential, central, crucial task--to transform ourselves from mere social creatures into community creatures. It is the only way that human evolution will be able to proceed. M. Scott Peck The Different Drum: Community-Making -

Oral History of Lee Felsenstein; 2008-05-07

Oral History of Lee Felsenstein Interviewed by: Kip Crosby Edited by: Dag Spicer Recorded: May 7, 2008 El Cerrito, California CHM Reference number: X4653.2008 © 2008 Computer History Museum Lee Felsenstein Oral History Kip Crosby: Hi, I'm Kip Crosby and I'm interviewing engineer and hardware designer Lee Felsenstein for the Computer History Museum. It is Wednesday, May 7, 2008. Lee, to my mind, you've always been an engineer. I've never known you as anything else, and I suppose I'd like to start with the forces and priorities within your family and your upbringing that made you into an engineer. Lee Felsenstein: Well, I can be considered a third generation engineer, although not really. I am an engineer in large part because my mother encouraged me in that direction. She was a five-year-old when her father died, William T. Price. He was an inventor who improved the diesel engine, apparently with what they then called solid injection, which is really liquid injection. Prior to that they used compressed air to blow the fuel mixture into the cylinder against a very high pressure. At any rate, before his work the diesel engine was for marine propulsion only. It was about three stories high and it included things like an air compressor and a Model-T engine or something like that to turn the air compressor. We heard stories of this from people, some of these engines survived. But William T. Price was able to make the engine reducible to the size of use in locomotives and ultimately automobiles. -

Community Memory: the First Public-Access Social Media System

Community Memory: The First Public-Access Social Media System Lee Felsenstein reprinted by permission from “Social Media – Archeology and Poetics” Judy Malloy, editor The MIT Press https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/social-media-archeology-and-poetics The first publicly available social media system, which opened in 1973 near the UC Berkeley campus, surprised its creators with the breadth of creative uses to which it was put by the users. Accessed through walk-up Teletype terminals on a mainframe time-sharing system, the Community Memory system was free, let users enter their own information and search commands directly, and relied on users’ imagination to define indexing words and make searches. Positioned in an entryway of a student-owned record store in front of a musician’s bulletin board, the system quickly attracted heavy usage by musicians, as might be expected, but also attracted items such as typewriter graphics, advertisements for a poet, and a spontaneous learning exchange item. The system went through three generations over a span of 19 years and was structured as a community information exchange available to noncomputer users. In the last generation, 10 terminals were base-level IBM PCs running text browsers on monochrome displays with coin acceptors attached. The mainframe had reduced to a 386 XT running a version of Unix. Various information-retrieval methods were implemented during the three generations, with the final system using both an indexed and a networked database structure so that items could be comments on other items as well as be organized by index words. A local theater critic has reported that he learned to write through the second-generation system as a teenager, trading rhetoric with his friends. -

Oral History Workshop

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303313115 How Education Made Computers Personal - Concept Paper for a Oral History Workshop Conference Paper · June 2016 CITATIONS READS 0 1,930 1 author: Jeremias Herberg IASS Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies Potsdam 22 PUBLICATIONS 24 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Co-Creation and Contemporary Policy Advice View project Social Transformation and Policy Advice in Lusatia View project All content following this page was uploaded by Jeremias Herberg on 18 May 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. TUE, JUNE 7, 2016, 15 – 20 pm LEUPHANA CAMPUS, HS1 EDT: 9 am – 14 pm, PDT: 6 – 11 am ORAL HISTORY WORKSHOP Stream https://webconf.vc.dfn.de/oral-history-workshop/ Discuss on facebook event, or mail [email protected] Read hclemuseum.wordpress.com/workshop HOW EDUCATION Organized by Liza Loop, LO*OP Center & Jeremias Herberg, Leuphana MADE COMPUTERS Contributors Clemens Apprich, Paula Bialski, Lee Felsenstein, Jérémy Grosman, Jeremias PERSONAL Herberg, Howard Rheingold, Liza Loop, Christina Vagt Since the 1960s California’s Counterculturalists LEE FELSENSTEIN considered both computers and education as Lee is an engineer involved in the creation of several countercultural move- tools for change. They lamented how computers ments and computer technologies. In 1963/1964 he was one of the few are “used to control people instead of to free technologists in the Free Speech Movement at University of California, them” and created educational and techno- Berkeley, where he later created the famous “Community Memory”. -

Fantasy, Apple Computer, and the Ethos of Silicon Valley

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2016 The Revolution Will Be Computed: Fantasy, Apple Computer, and the Ethos of Silicon Valley Misti Yang University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Repository Citation Yang, Misti, "The Revolution Will Be Computed: Fantasy, Apple Computer, and the Ethos of Silicon Valley" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2766. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9112216 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REVOLUTION WILL BE COMPUTED: FANTASY, APPLE COMPUTER, AND THE ETHOS OF SILICON VALLEY By Misti Yang Bachelor of Arts – American Studies Wellesley College 2001 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master -

Aaron Delwiche

Reality Hackers The Next Wave of Media Revolutionaries Aaron Delwiche (Editor), Evan Barnett, Andrew Coe, Patrick Crim, Kendra Doshier, Christopher Dudley, Ender Ergun, Ashley Funkhouser, Cole Gray, Sarah Hellman, John Key, Christopher Kradle, Patrick Lynch, Shepherd McAllister, Mark McCullough, Justin Michaelson, Alyson Miller, Robin Murdoch, Aaron Passer, Maricela Rios, Laura Schluckebier, Raelle Smiley, and Andrew Truelove. Additional help and inspiration from: Richard Bartle, Annalee Newitz, Ekaterina Sedia, Steven Shaviro, and R. U. Sirius. Creative Commons Licensed, 2010. This work is shared with the global community under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 license. You are free to share (copy, distribute and transmit) and remix the work for non-commercial purposes as long as you attribute the authors of this collection and of any work contained within. If you alter, transform or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. Please note that certain images in this volume are reproduced under the terms of more restrictive Creative Commons licenses (e.g. no remixing allowed). In all cases, the more restrictive license should apply. Deep gratitude to Delia Rios (Department of Communication) and Dr. Diane Smith (Office of Academic Affairs) for helping to make the Lennox seminar a reality. It could not have happened without their help. Special thanks also to JH and MH. 無論是在現實,在遊戲中的想像,你們兩個是最重要的事情在我的生活 Published by : Trinity University Department