Improving Federal Agency Planning and Accountability Progress Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

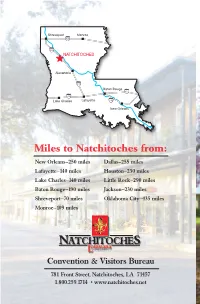

05 Natchitoches V-Guide

Miles to Natchitoches from: New Orleans—250 miles Dallas—255 miles Lafayette—140 miles Houston—230 miles Lake Charles—140 miles Little Rock—290 miles Baton Rouge—190 miles Jackson—230 miles Shreveport—70 miles Oklahoma City—435 miles Monroe—109 miles Convention & Visitors Bureau 781 Front Street, Natchitoches, LA 71457 1.800.259.1714 • www.natchitoches.net A Visitor’s Guide to: The Destination of Travelers Since 1714 781 Front Street, Natchitoches, LA 71457 1.800.259.1714 • www.natchitoches.net Authentic Culture Natchitoches Parish Top Things to do atchitoches, the original French colony in Louisiana, maintains its European in Natchitoches flavor through its architecture, heritage • Shop & Dine in Landmark Historic District and lifestyle. At the heart of this National – Experience authentic Creole Historic Landmark District lies Front & Cajun cuisine Street, a brick thoroughfare where – Sample a Natchitoches Meat Pie wrought iron balconies, restaurants and • Guided tours of Creole Plantations shops face the beautiful Cane River Lake. – Four sites open daily This area is home to the Cane River • Interpretive tour Fort St. Jean Baptiste National Heritage Area that includes the State Historic Site largest collection of Creole architecture in – Four State Historic Sites within a 25-miles radius North America along with the Cane River • Carriage tours Creole National Historical Park at – Historic tour and Steel Magnolia Oakland and Magnolia plantations. filming sites w Beginning in Natchitoches, the • Stroll along the scenic Cane River Lake El Camino Real de los Tejas (Highway 6 • See alligators up close and personal in Louisiana and Highway 21 in Texas,) • Experience the charm of our bed has existed for more than 300 years and and breakfast inns was designated as a National Historic • Museums, art galleries and Louisiana’s Trail in 2004. -

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo Chapter 1 Introduction This book is the result of research conducted for an exhibition on Louisiana history prepared by the Louisiana State Museum and presented within the walls of the historic Spanish Cabildo, constructed in the 1790s. All the words written for the exhibition script would not fit on those walls, however, so these pages augment that text. The exhibition presents a chronological and thematic view of Louisiana history from early contact between American Indians and Europeans through the era of Reconstruction. One of the main themes is the long history of ethnic and racial diversity that shaped Louisiana. Thus, the exhibition—and this book—are heavily social and economic, rather than political, in their subject matter. They incorporate the findings of the "new" social history to examine the everyday lives of "common folk" rather than concentrate solely upon the historical markers of "great white men." In this work I chose a topical, rather than a chronological, approach to Louisiana's history. Each chapter focuses on a particular subject such as recreation and leisure, disease and death, ethnicity and race, or education. In addition, individual chapters look at three major events in Louisiana history: the Battle of New Orleans, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Organization by topic allows the reader to peruse the entire work or look in depth only at subjects of special interest. For readers interested in learning even more about a particular topic, a list of additional readings follows each chapter. Before we journey into the social and economic past of Louisiana, let us look briefly at the state's political history. -

Historic Natchitoches®

February 2015 300 years of flags that have ® flown over Natchitoches. HHistoricistoric NNatchitochesatchitoches A Free Guide to Leisure and Attractions Courtesy of The Natchitoches Times FRANCE 1714-1763 SPAIN 1763-1801 FRANCE 1801-1803 UNITED STATES 1803-61 CONFEDERATE STATES 1861-65 UNITED STATES 1960-PRESENT Don’t ever build STATE FLAG OF LOUISIANA something you haven’t dreamed of, first. STORY ON PAGE 3 STEEL MAGNOLIAS AND OTHER CITY OF NATCHITOCHES TOUR MAPS PAGES 7-10 Page 2 HISTORIC NATCHITOCHES February 2015 Inside...Inside... Mardi Gras Comes to Natchitoches .......................................................Page 4 En Plein air .......................................................Page 5 Welcome to Natchitoches: The Story of Melrose .......................................................Page 6 Enjoy your stay in our historic town Maps, Walking Tours, NSU Tour and Cane River Tour ................................................Pages 7-10 Basilica of the Immaculate Conception .....................................................Page 11 The Last Cavalry Horse .....................................................Page 12 Mary Belle de Vargus .....................................................Page 14 The Came Out of the Sky .....................................................Page 16 ‘Historic Natchitoches’ is a monthly publication of The Natchitoches Times To advertise in this publication contact The Natchitoches Times P.O. Box 448 Natchitoches, LA 71458 On the Cover George Olivier celebrates 50 years of business in Natchitoches. -

TRADITIONAL VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE in CREOLE NATCHITOCHES Natchitoches and Cane River, Louisiana

Packet Thursday, October 31 to Sunday, November 3, 2019 TRADITIONAL VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE IN CREOLE NATCHITOCHES Natchitoches and Cane River, Louisiana GREEK REVIVAL SPONSOR Natchitoches Historic District Development Commission CREOLE PLANTATION SPONSOR LIVE OAK SPONSOR RoyOMartin Foundation Regional Construction LLC SPECIAL PARTNERS Cane River National Heritage Area Natchitoches Events Center Natchitoches Convention & Visitors Bureau Natchitoches Service League HOST ORGANIZATIONS Institute of Classical Architecture & Art: Louisiana Chapter Louisiana Architectural Foundation National Center for Preservation Training & Technology Cane River Creole National Historical Park Follow us on social media! Traditional Vernacular Architecture in Creole Natchitoches 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 About the Hosts 4 Institute of Classical Architecture & Art (ICAA) - Louisiana Chapter Louisiana Architecture Foundation (LAF) National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT) Cane River Creole National Historical Park Registration 5 Accommodations: Chateau Saint Denis Hotel 6 Foray itinerary 7 Destinations 9 Fort St. Jean Baptiste State Historic Site Samuel Guy House (1850) National Center for Preservation Training & Technology (NCPTT) Louisiana State Museum and Sports Hall of Fame (2013) Rue Beauport Riverfront (2017) Natchitoches Historic District (1984) St. Augustine (Isle Brevelle) Catholic Church (1829) Badin-Roque House (1769-1785) Yucca (Melrose) Plantation (1794-1814) Oakland Plantation (c. 1790) Cherokee Plantation (1839) -

National Heritage Areas

Charting a Future for National Heritage Areas A Report by the National Park System Advisory Board National Heritage Areas are places where natural, cultural, historic, and scenic resources combine to form a cohesive, nationally important landscape arising from patterns of human activity shaped by geography. These patterns make National Heritage Areas representative of the national experience through the physical features that remain and the traditions that have evolved in them. These regions are acknowledged by Congress for their capacity to tell nationally important stories about our nation. QUINEBAUG AND SHETUCKET RIVERS VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE CORRIDOR, LESLIE SWEETNAM; COVER PHOTO: BLACKSTONE RIVER VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA, SARAH LEEN Foreword In 004, the Director of the National Park Service asked the National Park System Advisory Board to review and report with recommendations on the appropriate role of the National Park Service in supporting National Heritage Areas. This is that report. The Board is a congressionally chartered body of twelve citizens appointed by the Secretary of the Interior. Established under the Historic Sites Act of 935, it is charged to provide advice on matters relating to operations in the parks and administration of the National Park Service. In preparing this report, the board sponsored meetings in four National Heritage Areas and consulted broadly with heritage area leaders, local and state-elected officials, community civic leaders and citizen groups, and National Park Service managers. National Heritage Areas represent a significant advance in conservation and historic preservation: large-scale, community-centered initiatives collaborating across political jurisdictions to protect nationally-important landscapes and living cultures. Managed locally, National Heritage Areas play a vital role in preserving the physical character, memories, and stories of our country, reminding us of our national origins and destiny. -

THE GEORGE WRIGHT Volume 19 2002< Number 4

FtRUTHE GEORGE WRIGHT M Volume 19 2002< Number 4 THE JOURNAL OF THE GEORGE WRIGHT SOCIETY Dedicated to the Protection, Preservation and Management of Cultural and Natural Parks and Reserves Through Research and Education The George Wright Society Origins Founded in 1980, The George Wright Society is organized for the purposes of promoting the application of knowledge, fostering communication, improving resource management, and providing information to improve public understanding and appreciation of the basic purposes of natural and cultural parks and equivalent reserves. The Society is dedicated to the protec tion, preservation, and management of cultural and natural parks and reserves through re search and education. Mission The George Wright Society advances the scientific and heritage values of parks and protected areas. The Society promotes professional research and resource stewardship across natural and cultural disciplines, provides avenues of communication, and encourage public policies that embrace these values. Our Goal The Society strives to be the premier organization connecting people, places, knowledge, and ideas to foster excellence in natural and cultural resource management, research, protection, and interpretation in parks and equivalent reserves. Board of Directors ROBERTJ. KRUMENAKER, President • Bayfield, Wisconsin LAURA E. S. GATES, Vice President • Pineville, Louisiana DWIGHT T. PITCAITHLEY, Treasurer • Reston, Virginia DENNIS B. FENN, Secretary • Flagstaff, Arizona GILLIAN BOWSER • Glennallen, Alaska PETER BRINKLEY • New York, New York MARIE BERTILLION COLLINS • Piedmont, California ABIGAIL B. MILLER • Alexandria, Virginia DAVIDJ. PARSONS • Florence, Montana RICHARD B. SMITH • Placitas, New Mexico STEPHEN WOODLEY • Chelsea, Quebec Executive Office DAVID HARMON, Executive Director P. O. Box 65 ROBERT M. LINN, Membership Coordinator Hancock, Michigan 49930-0065 USA EMILY DEKKER-FIALA. -

Cane River Lake, Louisiana

·-: .· .. ·_ o-~tC1") . SpeciaL.~source- Study. Environmental Ass.essment L: 0 (J l S. I .A N A ·tPANE RIVER ·· · · . Louisiana . HL'.SE. RETURN TO:. TECHmCJ\L n:r::::.~.m:N c:::nrn B&WScans C::rJVER SEiWiCE c::ViiEil ON MICROFILM ~i .. lL.{. _Z6C> ~- . fMTIO~Al PARK SERVICE . .· @.Print~d· on Recycled Paper Special Resource Study Environmental Assessment June 1993 Cane River Lake, Louisiana CANE RIVER Louisiana United States Department of the Interior • National Park Service • Denver Service Center SUMMARY As directed by Congress, the National Park Service has initiated a special resource study to identify and evaluate alternatives for managing, preserving, and interpreting historic structures, sites, and landscapes within the Cane River area of northwestern Louisiana, and how Creole culture developed in this area. The study includes an evaluation of resources for possible inclusion in the national park system using the requirements set forth in the NPS publication Criteria for Parklands, including criteria for national significance, suitability, and feasibility. The study area boundary includes Natchitoches Parish (pronounced Nack-a-tish), which still retains significant aspects of Creole culture. White Creoles of colonial Louisiana were born of French or Spanish parents before 1803. The tangible close of this period came with the formal establishment of United States presence as represented by Fort Jesup. Creoles of color emerged from freed slaves who owned plantations, developed their own culture, and enjoyed the respect and friendship of the dominant white Creole society. In Louisiana, Creole could refer to those of European, Afro-European heritage, or European-Indian heritage. The study area also includes Cane River Lake (originally the main channel for the Red River) and 4 miles of the Cane River to Cloutierville. -

Natalie Vivian Scott: the Origins, People and Times of the French Quarter Renaissance (1920-1930)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 Natalie Vivian Scott: The Origins, People and Times of the French Quarter Renaissance (1920-1930). John Wyeth Scott II Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Scott, John Wyeth II, "Natalie Vivian Scott: The Origins, People and Times of the French Quarter Renaissance (1920-1930)." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6924. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6924 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Slavery and Its Aftermath: the Archeological and Historical Record at Magnolia Plantation Christina E

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 Slavery and Its Aftermath: The Archeological and Historical Record at Magnolia Plantation Christina E. Miller Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES SLAVERY AND ITS AFTERMATH: THE ARCHEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL RECORD AT MAGNOLIA PLANTATION By Christina E. Miller A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Christina E. Miller defended on June 10, 2004. ____________________________________ Valerie J. Conner Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Glen H. Doran Outside Committee Member ____________________________________ James P. Jones Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This doctoral dissertation is dedicated to the following people: my mother Susan Elizabeth Wood, my father David Carruth Miller, my two brothers David Carruth Miller II and Justin James Miller, and my grandparents James Yates and Verl Wood, and Carruth and Junie Bell Miller. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My first and foremost acknowledgements are to Susan Elizabeth Wood, who is both my mother and a colleague. As a mother, she provided moral support, love, and a few threats throughout the writing process. As a colleague, we worked along side one another in the field and in the laboratory. She is responsible for the field drawings, SEAC maps, faunal analysis, and a great deal of the artifact analysis presented in this study. -

The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association Demythicizing History: Marie Therese Coincoin, Tourism, and the National Historical Landmarks Program

Fall 2012 Vol. L/11, No. 4 The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association Demythicizing History: Marie Therese Coincoin, Tourism, and the National Historical Landmarks Program By E L I Z A B E T H S H 0 W N M I L L s* Oral history plays a complicated role in scholarly disciplines. Bits and shards of mythos can bridge gaps in the documentary trail and suggest insight into matters that time obscures. Lore, legend, and family tradition, however, are also tricksters that betray those who trust them. Within different branches of a culture or a family, stories often wear starkly different guises. Many accounts spring from a core of truth, but pride, prejudice, ideology, and financial interests-as well as faulty memories can morph oral accounts into a caricature of reality. Moreover, many so-called traditions, when tracked to their roots, prove to be of quite-modern invention. Colonial Louisiana's legendary freedwoman Marie Therese dite Coincoin provides a case in point. She demonstrates how legend is born, how lore is nourished, and how well-documented facts can be ignored when they conflict with an appealing story. This article examines the historical evidence created by and about a black matriarch celebrated on Cane River for six decades. It reexamines the lore that has re-imaged her life, character, and 'The author is a historical consultant, curriculum advisor for the Boston University Center for Professional Education, and lead instructor and course coordinator at the Samford University Institute for Genealogy and Historical Research. She may be reached at www.evidencexplained.com. -

Marie Thérèse Coincoin, 1742–1816): a Test of “Oral History”

Documenting a Slave’s Birth, Parentage, and Origins (Marie Thérèse Coincoin, 1742–1816): A Test of “Oral History” By Elizabeth Shown Mills, CG, CGL, FASG, FNGS To prove identity, researchers prefer an original document in which someone with primary knowledge and sound memory makes an unbiased, direct, factual statement. Such documents are rare, however. Asserting identity requires fi nding and reassembling pieces of a life, fi tting them into a nuclear-family puzzle, and testing it against an extended family and a still larger community puzzle. This progressive expansion from one fragment of a person to a panorama embracing families and crossing community, national, and generational bounds is the essence of genealogical research. ocumenting ages, birthplaces, and identities for American colonials can be challenging, and fi nding adequate evidence for slaves even Dmore so. The problem can grow exponentially when a colonial slave is a local legend commemorated in the popular press by writers who did not fully investigate their stories—and by scholars who trusted oral accounts. When that slave is also credited with creating a National Historic Landmark and other structures in the Historic American Buildings Survey, separating myth from reality is essential.1 © Elizabeth Shown Mills ([email protected]) of the Samford University Institute of Genealogy and Historical Research is a past president of both the American Society of Genealogists and the Board for Certifi cation of Genealogists, as well as a former long-time editor of the NGS Quarterly. Her 2004 historical novel Isle of Canes, which follows Coincoin’s family for four generations, is based on three decades of research by Mills in the archives of six nations. -

C 75 NPS Form 10-900 |Jg£0 § W "* N°' 1024 -°018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service

^oo'i "c 75 NPS Form 10-900 |jg£0 § W "* N°' 1024 -°018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in "Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms" (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property________________________________________ historic name Melrose and Sinkola Plantations other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 3.75 miles southwest of Thomasville on US 319 city, town Thomasville (X) vicinity of county Thomas code GA 275 state Georgia code GA zip code 31799 (N/A) not for publication 3. Classification Ownership of Property: (X) private ( ) public-local ( ) public-state ( ) public-federal Category of Property ( ) building(s) (X) district ( ) site ( ) structure ( ) object Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing buildings 50 0 sites 1 0 structures 3 0 objects 0 0 total 54 0 NOTE: 2 structures are undocumented and are not listed. Contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60.