National Heritage Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE EXPLORERS by Richard F. Pourade CHAPTER ONE: BEFORE

THE EXPLORERS By Richard F. Pourade CHAPTER ONE: BEFORE THE EXPLORERS San Diego was a well populated area before the first Spanish explorers arrived. The climate was wetter and perhaps warmer, and the land more wooded than now. The remnant of a great inland lake covered most of Imperial Valley. The San Diego River wandered back and forth over the broad delta it had formed between Point Loma and Old Town, alternately emptying into Mission Bay and San Diego Bay. The natural food supply was so abundant that the state as a whole supported an Indian population far greater than any equal area in the United States. The native population of the southern counties alone must have been at least 10,000. The early maps made of San Diego Bay by the Spanish explorers show the same general configuration as of today, except, of course, for the many changes in the shoreline made by dredging and filling in recent years. The maps, crudely drawn without proper surveys, vary considerably in detail. Thousands of years ago, in the late part of the Ice Age, Point Loma was an island, as were Coronado and North Island. Coronado used to be known as South Island. There was no bay, as we think of it now. A slightly curving coastline was protected by the three islands, of which, of course, Point Loma was by far the largest. What we now know as Crown Point in Mission Bay was a small peninsula projecting into the ocean. On the mainland, the San Diego and Linda Vista mesas were one continuous land mass. -

Arizona Historic Preservation Plan 2000

ARIZONAHistoric Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 ARIZONAHistoric Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 ARIZONASTATEPARKSBOARD Chair Executive Staff Walter D. Armer, Jr. Kenneth E. Travous Benson Executive Director Members Renée E. Bahl Suzanne Pfister Assistant Director Phoenix Jay Ream Joseph H. Holmwood Assistant Director Mesa Mark Siegwarth John U. Hays Assistant Director Yarnell Jay Ziemann Sheri Graham Assistant Director Sedona Vernon Roudebush Safford Michael E. Anable State Land Commissioner ARIZONA Historic Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 StateHistoricPreservationOffice PartnershipsDivision ARIZONASTATEPARKS 5 6 StateHistoricPreservationOffice 3 4 PartnershipsDivision 7 ARIZONASTATEPARKS 1300WestWashington 8 Phoenix,Arizona85007 1 Tel/TTY:602-542-4174 2 http://www.pr.state.az.us ThisPlanUpdatewasapprovedbythe 9 11 ArizonaStateParksBoardonMarch15,2001 Photographsthroughoutthis 10 planfeatureviewsofhistoric propertiesfoundwithinArizona 6.HomoloviRuins StateParksincluding: StatePark 1.YumaCrossing 7.TontoNaturalBridge9 StateHistoricPark StatePark 2.YumaTerritorialPrison 8.McFarland StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark 3.Jerome 9.TubacPresidio StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark Coverphotographslefttoright: 4.FortVerde 10.SanRafaelRanch StateHistoricPark StatePark FortVerdeStateHistoricPark TubacPresidioStateHistoricPark 5.RiordanMansion 11.TombstoneCourthouse McFarlandStateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark YumaTerritorialPrisonStateHistoricPark RiordanMansionStateHistoricPark Tombstone Courthouse Contents Introduction 1 Arizona’s -

National Heritage Areas Congress Has Designated 55 National Heritage Areas (Nhas) to Recognize the Unique National Significance of a Region’S Sites and History

^ NATIONAL PARK SERVICE National Heritage Areas Congress has designated 55 National Heritage Areas (NHAs) to recognize the unique national significance of a region’s sites and history. Through local and regional partnerships with the National Park Service (NPS), these large lived-in landscapes connect heritage conservation with recreation and economic development. NHAs may be managed A site of the Journey Through Hallowed Ground National Heritage by federal commissions, nonprofit groups, Area, Harper’s Ferry National Historical Park in West Virginia tells a diverse, multi-layered history. Some of the stories the universities, and state agencies or municipal park interprets includes John Brown’s attack on slavery, Harriet authorities, guided by a management plan Tubman’s heroic efforts on Underground Railroad, the arrival of the first successful American railroad, the largest surrender of approved by the Secretary of the Interior. Through Federal troops during the Civil War, and the education of former slaves in one of the earliest integrated schools in the United this partnership strategy, heritage areas combine States. historic preservation, cultural and natural resource PHOTO BY FRANK KEHREN conservation, local and regional preservation planning, and heritage education and tourism. FY 2022 Appropriations Request Background National Heritage Areas are Please support $32 million for National Heritage Areas in the FY partnerships among the National 2022 Interior Appropriations bill. Park Service, states, and local communities, in which the NPS APPROPRIATIONS BILL: Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies supports state and local conservation AGENCY: National Park Service through federal recognition, seed ACCOUNT: National Recreation and Preservation money, and technical assistance. ACTIVITY: Heritage Partnership Programs/National Heritage Areas NHAs are designated by individual legislation with specific provisions Recent Funding History: for operation unique to the area’s FY 2019 Enacted Funding: $20.321 million specific resources and desired goals. -

State of the Park Report, Salem Maritime National Historic Site

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior STATE OF THE PARK REPORT Salem Maritime National Historic Site Salem, Massachusetts April 2013 National Park Service 2013 State of the Park Report for Salem Maritime National Historic Site State of the Park Series No. 7. National Park Service, Washington, D.C. On the cover: The tall ship, Friendship of Salem, the Custom House, Hawkes House, and historic wharves at Salem Maritime Na- tional Historic Site. (NPS) Disclaimer. This State of the Park report summarizes the current condition of park resources, visitor experience, and park infra- structure as assessed by a combination of available factual information and the expert opinion and professional judgment of park staff and subject matter experts. The internet version of this report provides the associated workshop summary report and additional details and sources of information about the findings summarized in the report, including references, accounts on the origin and quality of the data, and the methods and analytic approaches used in data collection and assessments of condition. This report provides evaluations of status and trends based on interpretation by NPS scientists and managers of both quantitative and non-quantitative assessments and observations. Future condition ratings may differ from findings in this report as new data and knowledge become available. The park superintendent approved the publication of this report. SALEM MARITIME NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 State of the Park Summary Table 3 Summary of Stewardship Activities and Key Accomplishments to Maintain or Improve Priority Resource Condition: 5 Key Issues and Challenges for Consideration in Management Planning 6 Chapter 1. -

Partnerships Annual Report

PARTNERSHIPS 1988 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ABRAHAM LINCOLN BIRTHPLACE ACADIA ADAMS AGATE FOSSIL BEDS ALAGNAK ALIBATES FLINT QUARRIES ALLEGHENY PORTAGE RAILROAD AMERICAN AMISTAD ANDERSONVILLE ANDREW JOHNSON ANIAKCHAK ANTIETAM APOSTLE ISLANDS APPALACHIAN APPOMATTOX COURT HOUSE ARCHES ARKANSAS POST ARLINGTON HOUSE ASSATEAGUE ISLAND AZTEC RUINS BADLANDS BANDELIER BENJAMIN FRANKLIN BENT SOLD FORT BERING LAND BRIDGE BIG BEND BIG CYPRESS BIG HOLE BIG SOUTH FORK BIG THICKET BIGHORN CANYON BISCAYNE BLACK CANYON OF THE GUNNISON BLACKSTONE RIVER VALLEY BLUE RIDGE BLUESTONE BOOKER T.WASHINGTON BOSTON AFRICAN AMERICAN BOSTON BRICES CROSS ROADS BRYCE CANYON BUCK ISLAND REEF BUFFALO CABRILLO CANAVERAL CANYON DECHELLY CANYONLANDS CAPE COD CAPE HATTERAS CAPE KRUSEN STERN CAPE LOOKOUT CAPITOL REEF CAPULIN VOLCANO CARL SANDBURG HOME CARLSBAD CAVERNS CASA GRANDE CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS CASTLE CLINTON CATOCTIN MOUNTAIN CEDAR BREAKS CHACO CULTURE CHAMIZAL CHANNEL ISLANDS CHARLES PINCKNEY CHATTAHOOCHEE RIVER CHESAPEAKE & OHIO CANAL CHICAGO PORTAGE CHICKAMAUGA & CHATTANOOGA CHICKASAW CHIMNEY ROCK CHIRICAHUA CHRISTIANSTED CITY OE ROCKS CLARA BARTON COLONIAL COLORADO CONGAREE SWAMP CONSTITUTION GARDENS CORONADO COULEE DAM COWPENS CRATER LAKE CRATERS OF THE MOON CUMBERLAND GAP CUMBERIAND ISLAND CURECANTI CUSTER BATTLEFIELD CUYAHOGA VALLEY DAVID BERGER DESOTO DEATH VALLEY DELAWARE WATER GAP DELAWARE DENALI DEVILS POSTPILE DEVILS TOWER DINOSAUR EBEYS LANDING EDGAR ALLEN POE EDISON EFFIGY MOUNDS EISENHOWER EL MALPAIS ELMORRO ELEANOR ROOSEVELT EUGENE O'NEILL -

2016 PEIR, Draft December 2015

3.5 CULTURAL RESOURCES This section of the Program Environmental Impact Report (PEIR) describes cultural resources in the SCAG region, discusses the potential impacts of the proposed 2016 Regional Transportation Plan/Sustainable Communities Strategy (“2016 RTP/SCS,” “Plan,” or “Project”) on cultural resources, identifies mitigation measures for the impacts, and evaluates the residual impacts. Cultural resources were evaluated in accordance with Appendix G of the 2015 State California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) Guidelines. Cultural resources within the SCAG region were evaluated at a programmatic level of detail, in relation to the general plans of the six counties and 191 cities within the SCAG region; review of general information characterizing the paleontological resources that have been reported from the SCAG region and review of Dibblee maps of geology and soils; general information characterizing prehistoric and historic human occupation within the SCAG region; general sensitivity of the SCAG region with respect to Native American Sacred sites and tribal cultural resources available through coordination with the Native American Heritage Commission (NAHC) and direct outreach to tribal governments within the SCAG region, including two Native American consultation workshops hosted by SCAG during preparation of the 2016 RTP/SCS and related PEIR; and review of known cemeteries in the SCAG region; a review of related literature germane to the SCAG region; as well as a review of SCAG’s 2012 RTP/SCS PEIR.1 Cultural resources within the SCAG region are recorded in the paleontological fossils; archeological sites and artifacts, historic sites, artifacts, structures and buildings; and the built environment. There is a rich record of archived fossils that are estimated to represent over 500 million years.2 The archaeological record provides evidence of over thousands of years of human occupation. -

SAMA Annual Report, FY2008

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Salem Maritime National Historic Site Saugus Iron Works National Historic SIte Superintendent’s Annual Narrative Report Fiscal Year 2009 Superintendent’s Annual Narrative Report Fiscal Year 2009 Salem Maritime National Historic Site Salem, Massachusetts Saugus Iron Works National Historic SIte Saugus, Massachusetts On the cover: Youth activities were a major focus of programming at Salem Maritime and Saugus Iron Works in FY2009 Top: a young member of the Boys and Girls clubs enjoys planting native species at Saugus Iron Works during the First Bloom activity in August, 2008. Bottom left: local students learn how to use a capstan from NPS volunteer Stu Gralnik during the Friendship Education Pilot Overnight Program. Bottom right: First Jobs studens learn how to apply gold leaf to wooden lettering from NPS painter Steven Abbott. NPS photos. Contents Introduction 5 Partnerships and Volunteers 33 Overview of the Year’s Conclusion 35 Most Significant Activities, Accomplishments, Trends, or Issues 7 Activities and Trends 9 Accomplishments 11 The Year’s Issues 15 Appendix A 37 The Divisions 15 Administration 17 Interpretation and Education 19 Maintenance 23 Marine and Special Programs 25 Resources Stewardship 27 Natural Resources Management 27 Cultural Resouces Management 28 Resource and Visitor Protection 31 Opposite above: the replica tall ship Friendship in dry dock at Boothbay Harbor Shipyard in Boothbay Harbor, Maine. NPS photo. SAMA/SAIR FY2009 Annual Narrative Report INTRODUCTION Salem Maritime National Historic Site and Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site are discrete National Park Service units that were merged under a single administration in 1998. -

An Evaluation of 12 National Heritage Areas

AN EVALUATION OF 12 NATIONAL HERITAGE AREAS In 2016, the National Park Service will celebrate its 100th birthday. By any objective measure, the past century has been a resounding success for the National Park Service as it has evolved into the most effective natural and historic resource preservation institution in the world. But despite its past success, future challenges abound. Not the least of these will be in the area of funding. In August of 2011, Congress enacted legislation that will reduce government-wide federal spending by more than $1 trillion over the next decade. Like other federal agencies and departments, this action will necessarily constrain federal funding of the National Park System. At the same time, the American public has not shown any sign of tiring of their national parks or desiring reductions in park opportunities. This is especially true in growing urban areas. To meet these seemingly incongruent realities, the National Park Service will be required to appreciably expand its current use of public-private partnerships. National Heritage Areas are a model for how such partnerships can create dynamic, business-oriented approaches to our nation’s preservation and conservation opportunities and needs. National Heritage Areas, some of which have been in operation for more than two decades, are grassroots, community- driven organizations that enhance local economic development by bringing to life historic preservation, natural resource conservation, recreation, and heritage tourism projects at a fraction of the cost of a traditional national park. By working in conjunction with local business and civic leaders, National leveraging these dollars four-fold and undertaking the timely implementation of projects in a more Heritage Areas have significantly compounded the effectiveness of federal tax dollars by routinely entrepreneurial environment. -

A Call to Action U.S

2014 National Park Service A Call to Action U.S. Department of the Interior Collaborating Beyond our Boundaries Into the Next Century Northeast Region Page 2 Anchor A Call to Action Defined Nearly 100 years ago, America called on the National Park Service (NPS) to preserve our past and promote enjoyment of our national treasures through the 1916 Organic Act. Our country may have changed since then, but not the role of the NPS as the caretaker of America’s most important places. A Call to Action is the strategic action plan of the NPS to advance our collaborative mission of stewardship and engagement into the next century. The plan describes specific goals and measurable actions that plot a new direction for the NPS as it nears its second century. Explore A Call to Action goals here Cover photo: Children place flowers on a stone wall at a special commemoration during the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Fredericksburg. This page: A reenactor portraying a bugler sergeant of the U.S. Army Signal Corps proudly waves the colors. Page 3 Anchor Northeast Region National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2014 Park Statistics 50 formal park partners working on behalf of national parks in the Northeast Region 3,185 school districts reside within the Northeast Region 10 parks participated in the Artist-in-Residence program 330 million dollars have been appropriated by the U.S. Congress in 15 separate programs toward Hurricane Sandy recovery 51,000 volunteers contributed almost 1.4 million hours of labor 10 webcams provide 24/7 viewing -

Outdoor Recreation Recreation Outdoor Massachusetts the Wildlife

Photos by MassWildlife by Photos Photo © Kindra Clineff massvacation.com mass.gov/massgrown Office of Fishing & Boating Access * = Access to coastal waters A = General Access: Boats and trailer parking B = Fisherman Access: Smaller boats and trailers C = Cartop Access: Small boats, canoes, kayaks D = River Access: Canoes and kayaks Other Massachusetts Outdoor Information Outdoor Massachusetts Other E = Sportfishing Pier: Barrier free fishing area F = Shorefishing Area: Onshore fishing access mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/fba/ Western Massachusetts boundaries and access points. mass.gov/dfw/pond-maps points. access and boundaries BOAT ACCESS SITE TOWN SITE ACCESS then head outdoors with your friends and family! and friends your with outdoors head then publicly accessible ponds providing approximate depths, depths, approximate providing ponds accessible publicly ID# TYPE Conservation & Recreation websites. Make a plan and and plan a Make websites. Recreation & Conservation Ashmere Lake Hinsdale 202 B Pond Maps – Suitable for printing, this is a list of maps to to maps of list a is this printing, for Suitable – Maps Pond Benedict Pond Monterey 15 B Department of Fish & Game and the Department of of Department the and Game & Fish of Department Big Pond Otis 125 B properties and recreational activities, visit the the visit activities, recreational and properties customize and print maps. mass.gov/dfw/wildlife-lands maps. print and customize Center Pond Becket 147 C For interactive maps and information on other other on information and maps interactive For Cheshire Lake Cheshire 210 B displays all MassWildlife properties and allows you to to you allows and properties MassWildlife all displays Cheshire Lake-Farnams Causeway Cheshire 273 F Wildlife Lands Maps – The MassWildlife Lands Viewer Viewer Lands MassWildlife The – Maps Lands Wildlife Cranberry Pond West Stockbridge 233 C Commonwealth’s properties and recreation activities. -

Heritage Areas: Background, Proposals, and Current Issues

Heritage Areas: Background, Proposals, and Current Issues Updated July 22, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33462 Heritage Areas: Background, Proposals, and Current Issues Summary Over more than 30 years, Congress has established 55 national heritage areas (NHAs) to commemorate, conserve, and promote important natural, scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational resources. NHAs are partnerships among the National Park Service (NPS), states, and local communities, in which the NPS supports state and local conservation through federal recognition, seed money, and technical assistance. Unlike lands within the National Park System, which are federally owned and managed, lands within heritage areas typically remain in state, local, or private ownership or a combination thereof. Supporters of heritage areas argue that NHAs protect lands and traditions and promote tourism and community revitalization. Opponents, however, contend that NHAs may be burdensome or costly and may lead to federal control over nonfederal lands. There is no comprehensive statute that establishes criteria for designating NHAs or provides standards for their funding and management. Rather, particulars for each area are provided in the area’s enabling legislation. Congress designates a management entity, usually nonfederal, to coordinate the work of the partners. This entity typically develops and implements a plan for managing the NHA, in collaboration with other parties. Once approved by the Secretary of the Interior, the management plan becomes the blueprint for managing the area. NHAs might receive funding from a wide variety of sources. Congress typically determines federal funding for NHAs in annual appropriations laws for Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies. NHAs can use federal funds for many purposes, including staffing, planning, and executing projects. -

05 Natchitoches V-Guide

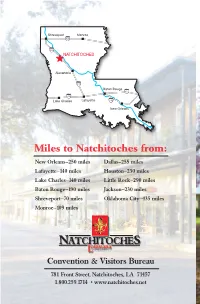

Miles to Natchitoches from: New Orleans—250 miles Dallas—255 miles Lafayette—140 miles Houston—230 miles Lake Charles—140 miles Little Rock—290 miles Baton Rouge—190 miles Jackson—230 miles Shreveport—70 miles Oklahoma City—435 miles Monroe—109 miles Convention & Visitors Bureau 781 Front Street, Natchitoches, LA 71457 1.800.259.1714 • www.natchitoches.net A Visitor’s Guide to: The Destination of Travelers Since 1714 781 Front Street, Natchitoches, LA 71457 1.800.259.1714 • www.natchitoches.net Authentic Culture Natchitoches Parish Top Things to do atchitoches, the original French colony in Louisiana, maintains its European in Natchitoches flavor through its architecture, heritage • Shop & Dine in Landmark Historic District and lifestyle. At the heart of this National – Experience authentic Creole Historic Landmark District lies Front & Cajun cuisine Street, a brick thoroughfare where – Sample a Natchitoches Meat Pie wrought iron balconies, restaurants and • Guided tours of Creole Plantations shops face the beautiful Cane River Lake. – Four sites open daily This area is home to the Cane River • Interpretive tour Fort St. Jean Baptiste National Heritage Area that includes the State Historic Site largest collection of Creole architecture in – Four State Historic Sites within a 25-miles radius North America along with the Cane River • Carriage tours Creole National Historical Park at – Historic tour and Steel Magnolia Oakland and Magnolia plantations. filming sites w Beginning in Natchitoches, the • Stroll along the scenic Cane River Lake El Camino Real de los Tejas (Highway 6 • See alligators up close and personal in Louisiana and Highway 21 in Texas,) • Experience the charm of our bed has existed for more than 300 years and and breakfast inns was designated as a National Historic • Museums, art galleries and Louisiana’s Trail in 2004.