Plantation Networks in the Late Antebellum Deep South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Graduation Exercises Will Be Official

TheMONDAY, Graduation MAY THE EIGHTEENTH Exercises TWO THOUSAND AND FIFTEEN NINE O’CLOCK IN THE MORNING THOMAS K. HEARN, JR. PLAZA THE CARILLON: “Mediation from Thaïs” . Jules Massenet Raymond Ebert (’60), University Carillonneur William Stuart Donovan (’15), Student Carillonneur THE PROCESSIONAL . Led by Head Faculty Marshals THE OPENING OF COMMENCEMENT . Nathan O . Hatch President THE PRAYER OF INVOCATION . The Reverend Timothy L . Auman University Chaplain REMARKS TO THE GRADUATES . President Hatch THE CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREES . Rogan T . Kersh Provost Carlos Brito, Doctor of Laws Sponsor: Charles L . Iacovou, Dean, School of Business Stephen T . Colbert, Doctor of Humane Letters Sponsor: Michele K . Gillespie, Dean-Designate, Wake Forest College George E . Thibault, Doctor of Science Sponsor: Peter R . Lichstein, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine Jonathan L . Walton, Doctor of Divinity Sponsor: Gail R . O'Day, Dean, School of Divinity COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS . Stephen Colbert Comedian and Late Night Television Host THE HONORING OF RETIRING FACULTY FROM THE REYNOLDA CAMPUS Bobbie L . Collins, M .S .L .S ., Librarian Ronald V . Dimock, Jr ., Ph .D ., Thurman D. Kitchin Professor of Biology Jack D . Ferner, M .B .A ., Lecturer of Management J . Kendall Middaugh, II, Ph .D ., Associate Professor of Management James T . Powell, Ph .D ., Associate Professor of Classical Languages David P . Weinstein, Ph .D ., Professor of Politics and International Affairs FROM THE MEDICAL CENTER CAMPUS James D . Ball, M .D ., Professor Emeritus of Radiology William R . Brown, Ph .D ., Professor Emeritus of Radiology Frank S . Celestino, M .D ., Professor Emeritus of Family and Community Medicine Wesley Covitz, M .D ., Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics Robert L . -

Sm^X And/Or Historic: Y X/\

S.C. District #5 - Rep. Thomas S. Gettys Theme 5. Political and Military k( NATIONAL HISTORIC Affairs LANDMARKS) Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE S()uth Carolina COUNTY: NATIONAL REG ISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Sljmter INVENTOR Y - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENT RY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) *j // /.f$~t £o(&£/ U htf r~ ^iiiiiiiii^mimmimmmmi lllllilllililll^liiii^h COMMON: X^' Milford Plantation SM^X AND/OR HISTORIC: Y X/\ Sill ;:'x':':'*: '^^^SS^ii^^^^f: STREET AND NUMBER: 5t ts Nnr yi^/ *•* W CITY OR TOWN: P Pinewood V x 29125 V^vi^^^: STATE CODE COUNTY: ^^ lf)]\ \ \ O ^' CODE South Carolina 29 215 45 Sumter —— l- 085 |i|lil^|sp:jiili{ii::s- ;£'• :& iif CATEGORY TATUS ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP S (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC G District (X] Building Q Public Public Acquisition: CT] Qcc upied Yes: . , G Restricted G Site G Structure S Private G '" Process (— j UnQ ccupied | | Both G Being Considered r —i p res . G Unrestricted Q Object ervation work — i n progress ® No t PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 1 1 Agriculturol [ | Government ( | Park G Tronsp ortation G Comments G Commercial Q Industrial [X] Private Residence G Other fk Soecitv) G Educational I 1 Military | | Relig ous G Entertainment I 1 Museum G Scientific OWNER'S NAME: Mr. & Mrs. Wm. Reeve Clark STREET AND NUMBER: Milford Plantation CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODE Pinewood 2912<5 South Carolina 45 iff ,/::, ; <>!^^^&m&:, ^%P %J£t COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Sumter County Court House COUNTY: STREET AND NUMBER: Main Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE CODE Sumter South Carolina 45 29150 jlliilllllllllllilp;;.;^::;!:!)!! JN6 lilv E Y «i |:::,; . -

The E Slaved People of Patto Pla Tatio Brazoria Cou Ty

Varner-Hogg Plantation and State Historical Park THE ESLAVED PEOPLE OF PATTO PLATATIO BRAZORIA COUTY, TEXAS Research Compiled By Cary Cordova Draft Submitted May 22, 2000 Compiled by Cary Cordova [email protected] Varner-Hogg Plantation and State Historical Park Research Compiled By Cary Cordova THE ESLAVED PEOPLE OF PATTO PLATATIO BRAZORIA COUTY, TEXAS The following is a list of all people known to have been slaves on the Columbus R. Patton Plantation from the late 1830s to 1865 in West Columbia, Texas. The list is by no means comprehensive, but it is the result of compiling information from the probate records, deeds, bonds, tax rolls, censuses, ex-slave narratives, and other relevant historical documents. Each person is listed, followed by a brief analysis if possible, and then by a table of relevant citations about their lives. The table is organized as first name, last name (if known), age, sex, relevant year, the citation, and the source. In some cases, not enough information exists to know much of anything. In other cases, I have been able to determine family lineages and relationships that have been lost over time. However, this is still a work in process and deserves significantly more time to draw final conclusions. Patton Genealogy : The cast of characters can become confusing at times, so it may be helpful to begin with a brief description of the Patton family. John D. Patton (1769-1840) married Annie Hester Patton (1774-1843) and had nine children, seven boys and two girls. The boys were Columbus R. (~1812-1856), Mathew C. -

The Difficult Plantation Past: Operational and Leadership Mechanisms and Their Impact on Racialized Narratives at Tourist Plantations

THE DIFFICULT PLANTATION PAST: OPERATIONAL AND LEADERSHIP MECHANISMS AND THEIR IMPACT ON RACIALIZED NARRATIVES AT TOURIST PLANTATIONS by Jennifer Allison Harris A Dissertation SubmitteD in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public History Middle Tennessee State University May 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Kathryn Sikes, Chair Dr. Mary Hoffschwelle Dr. C. Brendan Martin Dr. Carroll Van West To F. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I cannot begin to express my thanks to my dissertation committee chairperson, Dr. Kathryn Sikes. Without her encouragement and advice this project would not have been possible. I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my dissertation committee members Drs. Mary Hoffschwelle, Carroll Van West, and Brendan Martin. My very deepest gratitude extends to Dr. Martin and the Public History Program for graciously and generously funding my research site visits. I’m deeply indebted to the National Science Foundation project research team, Drs. Derek H. Alderman, Perry L. Carter, Stephen P. Hanna, David Butler, and Amy E. Potter. However, I owe special thanks to Dr. Butler who introduced me to the project data and offered ongoing mentorship through my research and writing process. I would also like to extend my deepest gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Douglass for her continued professional sponsorship and friendship. The completion of my dissertation would not have been possible without the loving support and nurturing of Frederick Kristopher Koehn, whose patience cannot be underestimated. I must also thank my MTSU colleagues Drs. Bob Beatty and Ginna Foster Cannon for their supportive insights. My friend Dr. Jody Hankins was also incredibly helpful and reassuring throughout the last five years, and I owe additional gratitude to the “Low Brow CrowD,” for stress relief and weekend distractions. -

ROSEDOWN PLANTATION Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ROSEDOWN PLANTATION Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Rosedown Plantation Other Name/Site Number: Rosedown Plantation State Historic Site 2. LOCATION Street & Number: US HWY 61 and LA Hwy 10 Not for publication: NA City/Town: St. Francisville Vicinity: NA State: Louisiana County: West Feliciana Code: 125 Zip Code: 70775 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): __ Public-Local: _ District: X Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 14 buildings 1 __ sites 4 structures 13 objects 11 31 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NA NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ROSEDOWN PLANTATION Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Mayor V. Fairfield Improvement Company

Mayor v. Fairfield Improvement Company: The Public’s Apprehension to Accept Nineteenth Century Medical Advancements Ryan Wiggins Daniella Einik Baltimore Environmental History December 21, 2009 I. INTRODUCTION On November 20, 1895, Alcaeus Hooper stood before a crowd of politicians, family, friends, and supporters in Baltimore’s city hall. “We feel that the election just held is more than an unusual one,” Hooper bellowed, “[t]hat it has amounted to a revolution, and it demands a change in the personnel of the many offices under the control of the municipality. The revolution calls louder, however, for a change in the methods of administration.”1 Hooper was about to be inaugurated as Baltimore’s first Republican mayor in a generation. He was a reform candidate who had united Independent Democrats, Republicans, and the Reform League against Isaac Freeman Rasin’s Democratic political machine. Political bosses had dominated Baltimore and Maryland politics since the 1870s, acting as middlemen between the city’s powerful business tycoons and a governmental structure that they largely controlled. In 1895, reform won overwhelmingly at the state and city level.2 Many people were eager for a change they could believe in. In spite of initial gains, including election reform and moves towards greater municipal efficiency, optimism for progressive change in the Hooper administration quickly cooled amongst the Baltimore elite. Hooper refused to acknowledge patronage issues, and in spite of some public support, had considerable trouble with the city council.3 In early 1897, a dispute over the school board set Hooper and the city council against each other in the Maryland Court of Appeals. -

Discussion Question Answers “When Computers Wore Skirts:” Katherine Johnson, Christine Darden, and the “West Computers”

Discussion Question Answers “When Computers Wore Skirts:” Katherine Johnson, Christine Darden, and the “West Computers” 1. Compare Katherine Johnson’s and Christine Darden’s life and experience at NASA. How were their experiences similar? How were they different? - Both were hired for a seperated pool of women computers rather than higher-status engineers. - Johnson was hired for a segregated all-black computer pool, for Darden, the computer pool was all women, but it was mixed race. - Johnson calculated and programmed flight paths from known technical specifications. Darden designed experiments and did research to come up with new technologies and physical laws. - Johnson never became an administrator, but Darden became technical leader of NASA’s Sonic Boom Research Group and director of the Program Management Office. 2. When did electronic computers start being introduced into NASA? What were they like (appearance, size, etc.) and how did people use them? - early 1960s (1962). - Computers were the size or larger than refrigerators. NASA would have whole rooms full of large computers. - Computers were all controlled by punch cards. People like Katherine Johnson had to program the computers by putting the instructions on a card. 3. How were Katherine Johnson and Christine Darden recruited to work at NASA? How did they end up leaving the “computer pool”? - Katherine Johnson was told by her relatives that the Langley Research Center had just opened up the “computer pool” to black women. She applied and was accepted to the segregated “West Computers” group. - Katherine Johnson was loaned out to the Flight Mechanics branch for temporary work. She did such a good job there, the engineering head decided not to reurn her to the computer pool and she became a part of the flight mechanics (eventually the Spacecraft Controls) branch. -

CAJUNS, CREOLES, PIRATES and PLANTERS Your New Louisiana Ancestors Format Volume 2, Number 33

CAJUNS, CREOLES, PIRATES AND PLANTERS Your New Louisiana Ancestors Format Volume 2, Number 33 By Damon Veach SLAVE REBELLION: The Greater New Orleans Louis A. Martinet Society, through its President-Elect, Sharrolyn Jackson Miles, is laying the groundwork for an important event. January 2011 will be the Bicentennial of what has been passed down as the German Coast Uprising or Slave Rebellion. This society and other local attorneys and supporters are interested in commemorating the events surrounding the historic 1811 slave uprising which took place at the German Coast which is now part of St. John and St. Charles parishes. The revolt began on January 8, 1811 and was led by Charles Deslondes, a free person of color working as a laborer on the Deslondes plantation. During the insurrection, approximately 200 slaves escaped from their plantations and joined the insurgents as they marched 20 miles downriver toward New Orleans. The rebellion was quashed a couple of days later when a militia of planters led by Colonel Manuel Andry attacked them at Destrehan Plantation. According to reports, 95 slaves were killed in the aftermath including 18 who were tried and executed at the Destrehan Plantation and 11 who were tried and executed in New Orleans. The slaves were executed by decapitation or hanging and the heads of some of the slaves were placed on stakes at plantations as a warning to others. This organization feels that it is very important that Louisianans take the time to remember this historic revolt which has been documented as the largest slave revolt in United States history. -

05 Natchitoches V-Guide

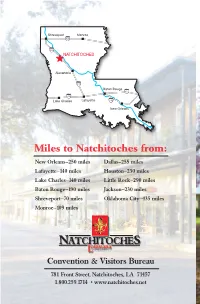

Miles to Natchitoches from: New Orleans—250 miles Dallas—255 miles Lafayette—140 miles Houston—230 miles Lake Charles—140 miles Little Rock—290 miles Baton Rouge—190 miles Jackson—230 miles Shreveport—70 miles Oklahoma City—435 miles Monroe—109 miles Convention & Visitors Bureau 781 Front Street, Natchitoches, LA 71457 1.800.259.1714 • www.natchitoches.net A Visitor’s Guide to: The Destination of Travelers Since 1714 781 Front Street, Natchitoches, LA 71457 1.800.259.1714 • www.natchitoches.net Authentic Culture Natchitoches Parish Top Things to do atchitoches, the original French colony in Louisiana, maintains its European in Natchitoches flavor through its architecture, heritage • Shop & Dine in Landmark Historic District and lifestyle. At the heart of this National – Experience authentic Creole Historic Landmark District lies Front & Cajun cuisine Street, a brick thoroughfare where – Sample a Natchitoches Meat Pie wrought iron balconies, restaurants and • Guided tours of Creole Plantations shops face the beautiful Cane River Lake. – Four sites open daily This area is home to the Cane River • Interpretive tour Fort St. Jean Baptiste National Heritage Area that includes the State Historic Site largest collection of Creole architecture in – Four State Historic Sites within a 25-miles radius North America along with the Cane River • Carriage tours Creole National Historical Park at – Historic tour and Steel Magnolia Oakland and Magnolia plantations. filming sites w Beginning in Natchitoches, the • Stroll along the scenic Cane River Lake El Camino Real de los Tejas (Highway 6 • See alligators up close and personal in Louisiana and Highway 21 in Texas,) • Experience the charm of our bed has existed for more than 300 years and and breakfast inns was designated as a National Historic • Museums, art galleries and Louisiana’s Trail in 2004. -

The 1811 Louisiana Slave Insurrection Nathan A

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2008 To kill whites: the 1811 Louisiana slave insurrection Nathan A. Buman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Buman, Nathan A., "To kill whites: the 1811 Louisiana slave insurrection" (2008). LSU Master's Theses. 1888. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1888 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO KILL WHITES: THE 1811 LOUISANA SLAVE INSURRECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In The Department of History by Nathan A. Buman B.A. Iowa State University 2006 August, 2008 ©Copyright 2008 [2008/Copyright] Nathan A. Buman All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the encouragement and support of my committee members, William J. Cooper, Gaines M. Foster, and Alicia P. Long. Had it not been for their advice, conversation, and patience in helping me to become a better writer, this thesis might have never come to fruition. Additionally I must thank John C. Rodrigue and Leonard Moore for assisting me in deciding to approach this topic in the first place and convincing me of the necessity of this study. -

DYESS COLONY REDEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN Dyess, Arkansas

DDYYEESSSS CCOOLLOONNYY RREEDDEEVVEELLOOPPMMEENNTT MMAASSTTEERR PPLLAANN Prepared for: Arkansas State University Jonesboro, Arkansas March 2010 Submitted by: DYESS COLONY REDEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN Dyess, Arkansas Prepared By: John Milner Associates, Inc. 535 North Church Street West Chester, Pennsylvania 19380 Tom Scofield, AICP – Project Director Terry Necciai, AIA – Planner Katherine Farnham – Historian Michael Falstad/Joy Bunch – Architectural Graphics April 2010 Acknowledgements During the course of preparing the Dyess Colony Redevelopment Master Plan for Arkansas State University, JMA was supported by several individuals who gave generously of their time, insight, and information. In particular we would like to thank the following individuals for their guidance and knowledge: Dr. Ruth Hawkins, Director of Arkansas Heritage SITES, Arkansas State University Elizabeth Wiedower, Director, Arkansas Delta Rural Development Heritage Initiative Mayor Larry Sims and the Board of Aldermen, Town of Dyess, Arkansas Senator Steve Bryles, Arkansas State Legislature Linda Hinton, Southern Tenant Farmers Museum, Tyronza, Arkansas Soozi Williams, Delta Area Museum, Marked Tree, Arkansas Doris Pounders, The Painted House, Lepanto, Arkansas Aaron Ruby, Ruby Architects, Inc., North Little Rock, Arkansas Paula Miles, Project Manager, Arkansas Heritage SITES, Arkansas State University Moriah & Elista Istre, graduate students, Heritage Studies Program, Arkansas State University Mayor Barry Harrison, Blytheville. Arkansas Liz Smith, Executive Director, -

Sexual Violence in the Slaveholding Regimes of Louisiana and Texas: Patterns of Abuse in Black Testimony

Sexual Violence in the Slaveholding Regimes of Louisiana and Texas: Patterns of Abuse in Black Testimony Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Andrea Helen Livesey June 2015 UAbstract This study is concerned with the sexual abuse of enslaved women and girls by white men in the antebellum South. Interviews conducted by the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s are studied alongside nineteenth-century narratives of the formerly enslaved in order to make calculations of the scale of abuse in the South, but also to discover which conditions, social spaces and situations were, and possibly still are, most conducive to the sexual abuse of women and girls. This thesis is separated into two parts. Part One establishes a methodology for working with testimony of the formerly enslaved and determines the scale of sexual abuse using all available 1930s interviews with people who had lived in Louisiana and Texas under slavery. This systematic quantitative analysis is a key foundation from which to interpret the testimony of abuse that is explored according to different forms of sexual violence in Part Two. It is argued that abuse was endemic in the South, and occurred on a scale that was much higher than has been argued in previous studies. Enslaved people could experience a range of white male sexually abusive behaviours: rape, sexual slavery and forced breeding receive particular attention in this study due to the frequency with which they were mentioned by the formerly enslaved. These abuses are conceptualised as existing on a continuum of sexual violence that, alongside other less frequently mentioned practices, pervaded the lives of all enslaved people.