Planning for Cane River Creole National Historical Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barthé, Darryl G. Jr.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. Doctorate of Philosophy in History University of Sussex Submitted May 2015 University of Sussex Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. (Doctorate of Philosophy in History) Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Summary: The Louisiana Creole community in New Orleans went through profound changes in the first half of the 20th-century. This work examines Creole ethnic identity, focusing particularly on the transition from Creole to American. In "becoming American," Creoles adapted to a binary, racialized caste system prevalent in the Jim Crow American South (and transformed from a primarily Francophone/Creolophone community (where a tripartite although permissive caste system long existed) to a primarily Anglophone community (marked by stricter black-white binaries). These adaptations and transformations were facilitated through Creole participation in fraternal societies, the organized labor movement and public and parochial schools that provided English-only instruction. -

Cane River, Louisiana

''ewe 'Know <Who <We !A.re'' An Ethnographic Ove1'View of the Creole Traditions & Community of Isle Brevelle & Cane River, Louisiana H.F. Gregory, Ph.D. Joseph Moran, M.A. I /'I "1\ 1'We Know Who We Are": I An Ethnographic Overview of the Creole Community and Traditions of I Isle Breve lie and Cane River, Louisiana I I I' I I 'I By H.F. Gregory, Ph.D. I Joseph Moran, M.A. I I I Respectfully Submitted to: Jean Lafitte National Historic Park and Preserve U.S. Department of the Interior I In partial fulfillment of Subagreement #001 to Cooperative Agreement #7029~4-0013 I I December, 1 996 '·1 I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I Errata Page i - I "Jean Lafitte National Historic Park and Preserve" should read, "Jean Lafitte National I Historical Park and Preserve ...." Please define "emic" as the point of view from the culture as opposed to the I anthropological, descriptive view of the culture - the outsider's point ofview(etic). I Page vi- "Dr. Allison Pena" should read, "Ms. Allison Pena. ." I Page 13 - I "The first was literary-folkloristic which resulted in local color novels and romantic history - all but 'outside' authors and artists ... "should read, "The first was literary-folkloristic which I resulted in local color and romantic history - all by 'outside' authors and artists ...." I Page 14 - "Whenever Creoles tried to explain who they were, who they felt they were, it ultimately was, and is, interpreted as an attempt to passer pour blanc" should read, "Whenever Creoles tried I to explain who they were, who they felt they were, it ultimately was, and is, interpreted as an I attempt to passer pour blanc, or to pass for white... -

Cane River Waterway Commission 244 Cedar Bend Natchez, Louisiana 71456 318-357-3007 Office

Cane River Waterway Commission 244 Cedar Bend Natchez, Louisiana 71456 318-357-3007 office The following Ordinance was introduced by _Mr. Methvin and Seconded by Mr. Paige , on the 18 day of September, 2018, to-wit: ORDINANCE NO. 2 OF 2018 AN ORDINANCE APPROVING A COOPERATIVE ENDEAVOR AGREEMENT WITH VICTOR JONES, SHERIFF OF NATCHITOCHES PARISH, LOUISIANA TO PROVIDE FOR PATROLS ON CANE RIVER LAKE AND TO PROVIDE FOR SUPPLEMENTAL BOATING ENFORCEMENT SERVICES, AND FURTHER AUTHORIZING THE CHAIRMAN OF THE COMMISSION, JAMES RHODES, TO EXECUTE THE COOPERATIVE ENDEAVOR AGREEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE COMMISSION AND SIGN ANY AND ALL OTHER NECESSARY DOCUMENTS ASSOCIATED THEREWITH WHEREAS, the Cane River Waterway Commission (sometimes hereinafter “Commission”) is a political subdivision of the State of Louisiana created by special act which may be found at Louisiana Revised Statutes 34:3261, et seq,; and WHEREAS FURTHER, the purpose of the Commission is to establish, operate and maintain the waterway system known as the Cane River Waterway, Louisiana R.S. 34:3262; and WHEREAS FURTHER, included among the powers and authority granted to the Commission under Louisiana R.S. 34:3269(13) is the authority to regulate the waterway and its use, which authority includes “…water traffic regulation, such as size and speed of boats and other vessels.”; and WHEREAS FURTHER, while the Cane River Waterway Commission has the authority to regulated water traffic on Cane River Lake, it does not have the police power necessary to enforce the regulations that it has and may -

Once Upon a Time in Louisiana

10th Annual LouisianaLouisiana StudiesStudies ConferenceConference Once Upon a Time in Louisiana September 21-22, 20182018 CAPA Building Free and open to the public Ferguson-Dennis Cemetery | Leesville, Louisiana, Way Home Photography | Belinda S. Diehl Poster designed by Matt DeFord Info: Louisiana Folklife Center (318) 357-4332 1 The 10th Annual Louisiana Studies Conference September 21-22, 2018 “Once Upon a Time in Louisiana” Conference Keynote Speakers: Katie Bickham and Tom Whitehead Conference Co-Chairs: Lisa Abney, Faculty Facilitator for Academic Research and Community College Outreach and Professor of English, Northwestern State University Jason Church, Materials Conservator, National Center for Preservation Technology and Training Charles Pellegrin, Professor of History and Director of the Southern Studies Institute, Northwestern State University Shane Rasmussen, Director of the Louisiana Folklife Center and Associate Professor of English, Northwestern State University Conference Programming: Jason Church, Chair Shane Rasmussen Conference Hosts: Leslie Gruesbeck, Associate Professor of Art and Gallery Director, Northwestern State University Greg Handel, Director of the School of Creative and Performing Arts, Associate Professor of Music and Interim Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Northwestern State University Selection Committees: Conference Presentations: Shane Rasmussen, Chair Jason Church NSU Louisiana High School Essay Contest: Shane Rasmussen, Chair Lisa Abney Jason Church 2 Lisa Davis, NSU National Writing Project -

Vegetable Variety Trial Program Conducted at Auburn University Is Initially Due to the Commitment of the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station (AAES) Administration

VE11 Bulletin 640 January 2000 f4 Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station Luther Waters, Director Auburn University Auburn, Alabama VLr.hIIIII 11.-114 hA I 4 I a t 0 ) 4 A CONTENTS Page Page Introduction ................ 1 Okra . .................... 65 Artichoke ................. Onion ................... 66 Asparagus ................. 4 Parsley .................. 71 Bean, Snap ................. 5 Parsnip .................. 72 Beet..... .. ......... 10 Pea, English ............... 73 Broccoli .................. 11 Pepper ................... 75 Brussel Sprout ............. 14 Potato, Irish............... 87 Cabbage, Head ............. 15 Pumpkin ................. 88 Cabbage, Chinese ........... 16 Radish ................... 92 Carrot ................... 22 Rhubarb .................. 94 Cauliflower... ........ 24 Rutabaga ................. 95 Collard..............................26 Southernpea ....................... 96 Corn, Sweet ....................... 27 Spinach............................. 97 Corn, Ornamental ............... 37 Sweetpotato ....................... 99 Cucumber, Slicer ............... 40 Tomato........................... 101 Eggplant ........................... 46 Turnip ............................ 113 Kale..................................48 Watermelon ..................... 114 Kohlrabi ........................... 49 Winter Squash ............... 121 Lettuce............................. 50 Yellow Summer Squash .... 124 Melons, Small .................. 57 Zucchini Squash .............. 127 (cantaloupe and honey dew) -

Understanding South Louisiana Through Literature

UNDERSTANDING SOUTH LOUISIANA THROUGH LITERATURE: FOLKTALES AND POETRY AS REPRESENTATIONS OF CULTURAL IDENTITY by ANNA BURNS (Under the direction of Dr. Nina Hellerstein) ABSTRACT Folktales represent particular cultural attitudes based on location, time period, and external and internal influences. Cultural identity traits appear through the storytellers, who emphasize these traits to continue cultural traditions. The folktales and poetry studied in this thesis show how various themes work together to form the Cajun and Creole cultures. The themes of occupation, music and dance, and values; religion, myth, and folk beliefs; history, violence, and language problems are examined separately to show aspects of Cajun and Creole cultures. Secondary sources provide cultural information to illustrate the attitudes depicted in the folktales and poetry. INDEX WORDS: Folktales, Poetry, Occupation, Religion, Violence, Cajun and Creole, Cultural Identity UNDERSTANDING SOUTH LOUISIANA THROUGH LITERATURE: FOLKTALES AND POETRY AS REPRESENTATIONS OF CULTURAL IDENTITY by ANNA BURNS B.A., Loyola University of New Orleans, 1998 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2002 ©2002 Anna Burns All Rights Reserved UNDERSTANDING SOUTH LOUISIANA THROUGH LITERATURE: FOLKTALES AND POETRY AS REPRESENTATIONS OF CULTURAL IDENTITY by ANNA BURNS Major Professor: Dr. Nina Hellerstein Committee: Dr. Doris Kadish Dr. Tim Raser Electronic Version Approved: Gordhan L. Patel Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2002 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to all those who have supported me in various ways through this journey and many others. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all those who have given me superior guidance and support during my studies, particulary Dr. -

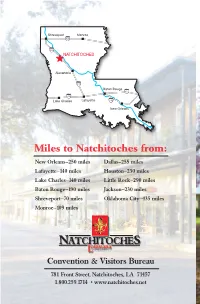

05 Natchitoches V-Guide

Miles to Natchitoches from: New Orleans—250 miles Dallas—255 miles Lafayette—140 miles Houston—230 miles Lake Charles—140 miles Little Rock—290 miles Baton Rouge—190 miles Jackson—230 miles Shreveport—70 miles Oklahoma City—435 miles Monroe—109 miles Convention & Visitors Bureau 781 Front Street, Natchitoches, LA 71457 1.800.259.1714 • www.natchitoches.net A Visitor’s Guide to: The Destination of Travelers Since 1714 781 Front Street, Natchitoches, LA 71457 1.800.259.1714 • www.natchitoches.net Authentic Culture Natchitoches Parish Top Things to do atchitoches, the original French colony in Louisiana, maintains its European in Natchitoches flavor through its architecture, heritage • Shop & Dine in Landmark Historic District and lifestyle. At the heart of this National – Experience authentic Creole Historic Landmark District lies Front & Cajun cuisine Street, a brick thoroughfare where – Sample a Natchitoches Meat Pie wrought iron balconies, restaurants and • Guided tours of Creole Plantations shops face the beautiful Cane River Lake. – Four sites open daily This area is home to the Cane River • Interpretive tour Fort St. Jean Baptiste National Heritage Area that includes the State Historic Site largest collection of Creole architecture in – Four State Historic Sites within a 25-miles radius North America along with the Cane River • Carriage tours Creole National Historical Park at – Historic tour and Steel Magnolia Oakland and Magnolia plantations. filming sites w Beginning in Natchitoches, the • Stroll along the scenic Cane River Lake El Camino Real de los Tejas (Highway 6 • See alligators up close and personal in Louisiana and Highway 21 in Texas,) • Experience the charm of our bed has existed for more than 300 years and and breakfast inns was designated as a National Historic • Museums, art galleries and Louisiana’s Trail in 2004. -

The Social-Construct of Race and Ethnicity: One’S Self-Identity After a DNA Test

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 4-2019 The Social-Construct of Race and Ethnicity: One’s Self-Identity after a DNA Test Kathryn Ann Wilson Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Kathryn Ann, "The Social-Construct of Race and Ethnicity: One’s Self-Identity after a DNA Test" (2019). Dissertations. 3405. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3405 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SOCIAL-CONSTRUCT OF RACE AND ETHNICITY: ONES’ SELF-IDENTITY AFTER A DNA TEST by Kathryn Wilson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Educational Leadership, Research and Technology Western Michigan University April 2019 Doctoral Committee: Gary Miron, Ph.D., Chair D. Eric Archer, Ph.D. June Gothberg, Ph.D. Copyright by Kathryn Wilson 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Gary Miron, for his continued belief that I would find my passion and complete this dissertation. Also, I would like to thank my dissertation advisory committee chair Professor Gary Miron, Ph.D., and committee members Assistant Professor D. Eric Archer, Ph.D., and Assistant Professor June Gothberg, Ph.D. for their advice and support. -

The Many Louisianas: Rural Social Areas and Cultural Islands

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Agricultural Experiment Station Reports LSU AgCenter 1955 The am ny Louisianas: rural social areas and cultural islands Alvin Lee Bertrand Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/agexp Recommended Citation Bertrand, Alvin Lee, "The am ny Louisianas: rural social areas and cultural islands" (1955). LSU Agricultural Experiment Station Reports. 720. http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/agexp/720 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the LSU AgCenter at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Agricultural Experiment Station Reports by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. % / '> HE MANY Ifpsiflnfls rnl Social llreiis Ituri^l Islands in No. 496 June 1955 Louisiana State University AND cultural and Mechanical College cricultural experiment station J. N. Efferson, Director I TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SUMMARY 33 INTRODUCTION 5 Objectives ^ Methodology 6 THE IMPORTANT DETERMINANTS OF SOCIO-CULTURAL HOMOGENEITY 9 School Expenditures per Student 9 Proportion of Land in Farms 9 Age Composition 10' Race Composition . 10 Level of Living 10 Fertility H THE RURAL SOCIAL AREAS OF LOUISIANA 11 Area I, The Red River Delta Area 11 Area II, The North Louisiana Uplands 14 Area III, The Mississippi Delta Area 14 Area IV, The North Central Louisiana Cut-Over Area 15 Area V, The West Central Cut-Over Area 15 Area VI, The Southwest Rice Area 16 Area VII, The South Central Louisiana Mixed Farming Area 17 Area VIII, The Sugar Bowl Area 17 Area IX, The Florida Parishes Area 18 Area X, The New Orleans Truck and Fruit Area ... -

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo Chapter 1 Introduction This book is the result of research conducted for an exhibition on Louisiana history prepared by the Louisiana State Museum and presented within the walls of the historic Spanish Cabildo, constructed in the 1790s. All the words written for the exhibition script would not fit on those walls, however, so these pages augment that text. The exhibition presents a chronological and thematic view of Louisiana history from early contact between American Indians and Europeans through the era of Reconstruction. One of the main themes is the long history of ethnic and racial diversity that shaped Louisiana. Thus, the exhibition—and this book—are heavily social and economic, rather than political, in their subject matter. They incorporate the findings of the "new" social history to examine the everyday lives of "common folk" rather than concentrate solely upon the historical markers of "great white men." In this work I chose a topical, rather than a chronological, approach to Louisiana's history. Each chapter focuses on a particular subject such as recreation and leisure, disease and death, ethnicity and race, or education. In addition, individual chapters look at three major events in Louisiana history: the Battle of New Orleans, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Organization by topic allows the reader to peruse the entire work or look in depth only at subjects of special interest. For readers interested in learning even more about a particular topic, a list of additional readings follows each chapter. Before we journey into the social and economic past of Louisiana, let us look briefly at the state's political history. -

Visitlakecharles 800-456-SWLA LAKE CHARLES | SULPHUR | WESTLAKE DEQUINCY | VINTON | IOWA Welcome Y’All! What's Inside?

VisitLakeCharles.org #VisitLakeCharles 800-456-SWLA LAKE CHARLES | SULPHUR | WESTLAKE DEQUINCY | VINTON | IOWA Welcome Y’all! What's Inside? Share Your Story ...........................................................4 Casino Time ...................................................................6 Lake Charles/Southwest Louisiana Arts & Culture ...............................................................8 - The Gateway to Cajun Country Galleries & Museums Performing Arts Adventure and exploration await with a diverse offering Cultural Districts of culture, music, world-famous food, festivals, the great Where to Eat? .............................................................. 12 outdoors, casino gaming, top name entertainment and Dining Options historic attractions. So, unwind & have fun! Southwest Louisiana Boudin Trail Stop by the convention & visitors bureau, 1205 N. Fun Food Facts Lakeshore Drive, while you are in town. Visit with our Culinary Experiences friendly staff, have a cup of coffee and get tips on how to Cuisine & Recipes make your stay as memorable as possible. Creole vs. Cajun ...........................................................23 Music Scene .................................................................24 Connect with us & share your adventures! Looking for Live Music? facebook.com/lakecharlescvb Nightlife www.visitlakecharles.org/blog #visitlakecharles Adventure Tourism ......................................................27 Get Your Adventure On! Creole Nature Trail Adventure Point ...........................28 -

The Music of Louisiana: Cajuns, Creoles and Zydeco

The Music of Louisiana: Cajuns, Creoles and Zydeco Carole Poindexter-Sylvers INTRODUCTION The music and cuisine of southern Louisiana experienced a renaissance during the 1980s. Zydeco musicians and recording artists made appearances on morning talk shows, Cajun and Creole restaurants began to spring up across the nation, and celebrity chefs such Paul Prudhomme served as a catalyst for the surge in interest. What was once unknown by the majority of Americans and marginalized within the non-French speaking community in Louisiana had now become a national trend. The Acadians, originally from Acadia, Nova Scotia, were expelled from Canada and gradually became known as Cajuns. These Acadians or Cajuns proudly began teaching the lingua franca in their francophone communities as Cajun French, published children‘s books in Cajun French and school curricula in Cajun French. Courses were offered at local universities in Cajun studies and Cajun professors published scholarly works about Cajuns. Essentially, the once marginalized peasants had become legitimized. Cajuns as a people, as a culture, and as a discipline were deemed worthy of academic study stimulating even more interest. The Creoles of color (referring to light-skinned, French-speaking Negroid people born in Louisiana or the French West Indies), on the other hand, were not acknowledged to the same degree as the Cajuns for their autonomy. It would probably be safe to assume that many people outside of the state of Louisiana do not know that there is a difference between Cajuns and Creoles – that they are a homogeneous ethnic or cultural group. Creoles of color and Louisiana Afro-Francophones have been lumped together with African American culture and folkways or southern folk culture.