THE GEORGE WRIGHT Volume 19 2002< Number 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Difficult Plantation Past: Operational and Leadership Mechanisms and Their Impact on Racialized Narratives at Tourist Plantations

THE DIFFICULT PLANTATION PAST: OPERATIONAL AND LEADERSHIP MECHANISMS AND THEIR IMPACT ON RACIALIZED NARRATIVES AT TOURIST PLANTATIONS by Jennifer Allison Harris A Dissertation SubmitteD in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public History Middle Tennessee State University May 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Kathryn Sikes, Chair Dr. Mary Hoffschwelle Dr. C. Brendan Martin Dr. Carroll Van West To F. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I cannot begin to express my thanks to my dissertation committee chairperson, Dr. Kathryn Sikes. Without her encouragement and advice this project would not have been possible. I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my dissertation committee members Drs. Mary Hoffschwelle, Carroll Van West, and Brendan Martin. My very deepest gratitude extends to Dr. Martin and the Public History Program for graciously and generously funding my research site visits. I’m deeply indebted to the National Science Foundation project research team, Drs. Derek H. Alderman, Perry L. Carter, Stephen P. Hanna, David Butler, and Amy E. Potter. However, I owe special thanks to Dr. Butler who introduced me to the project data and offered ongoing mentorship through my research and writing process. I would also like to extend my deepest gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Douglass for her continued professional sponsorship and friendship. The completion of my dissertation would not have been possible without the loving support and nurturing of Frederick Kristopher Koehn, whose patience cannot be underestimated. I must also thank my MTSU colleagues Drs. Bob Beatty and Ginna Foster Cannon for their supportive insights. My friend Dr. Jody Hankins was also incredibly helpful and reassuring throughout the last five years, and I owe additional gratitude to the “Low Brow CrowD,” for stress relief and weekend distractions. -

Laura Plantation Mute Victims of Katrina: Four Louisiana Landscapes at Risk

The Cultural Landscape Foundation VACHERIE , LOUISIANA Laura Plantation Mute Victims of Katrina: Four Louisiana Landscapes at Risk In 1805, Guillaume Duparc, a French veteran of the American Revolution, took possession of a 12,000-acre site just four miles downriver from Oak Alley Plantation in St. James Parish. With only seventeen West African slaves, he began to clear the land, build a home and grow sugarcane on the site of a Colapissa Indian village. This endeavor, like many others, led to a unique blending of European, African and Native American cultures that gave rise to the distinctive Creole culture that flourished in the region before Louisiana became part of the United States . Today, Laura Plantation offers a rare view of this non-Anglo-Saxon culture. Architectural styles, family traditions and the social/political life of the Creoles have been illuminated through extensive research and documentation. African folktales, personal memoirs and archival records have opened windows to Creole plantation life – a life that was tied directly to the soil with an agrarian-based economy, a taste for fine food and a constant battle to find comfort in a hot, damp environment. Laura Plantation stands today as a living legacy dedicated to the Creole culture. HISTORY Situated 54 miles above New Orleans on the west bank of the Mississippi River, the historic homestead of Laura Plantation spreads over a 14-acre site with a dozen buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The main house along with Creole cottages, slave cabins and farm buildings rest on an elevated landmass of rich alluvial silt created by a geological fault. -

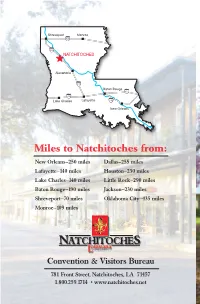

05 Natchitoches V-Guide

Miles to Natchitoches from: New Orleans—250 miles Dallas—255 miles Lafayette—140 miles Houston—230 miles Lake Charles—140 miles Little Rock—290 miles Baton Rouge—190 miles Jackson—230 miles Shreveport—70 miles Oklahoma City—435 miles Monroe—109 miles Convention & Visitors Bureau 781 Front Street, Natchitoches, LA 71457 1.800.259.1714 • www.natchitoches.net A Visitor’s Guide to: The Destination of Travelers Since 1714 781 Front Street, Natchitoches, LA 71457 1.800.259.1714 • www.natchitoches.net Authentic Culture Natchitoches Parish Top Things to do atchitoches, the original French colony in Louisiana, maintains its European in Natchitoches flavor through its architecture, heritage • Shop & Dine in Landmark Historic District and lifestyle. At the heart of this National – Experience authentic Creole Historic Landmark District lies Front & Cajun cuisine Street, a brick thoroughfare where – Sample a Natchitoches Meat Pie wrought iron balconies, restaurants and • Guided tours of Creole Plantations shops face the beautiful Cane River Lake. – Four sites open daily This area is home to the Cane River • Interpretive tour Fort St. Jean Baptiste National Heritage Area that includes the State Historic Site largest collection of Creole architecture in – Four State Historic Sites within a 25-miles radius North America along with the Cane River • Carriage tours Creole National Historical Park at – Historic tour and Steel Magnolia Oakland and Magnolia plantations. filming sites w Beginning in Natchitoches, the • Stroll along the scenic Cane River Lake El Camino Real de los Tejas (Highway 6 • See alligators up close and personal in Louisiana and Highway 21 in Texas,) • Experience the charm of our bed has existed for more than 300 years and and breakfast inns was designated as a National Historic • Museums, art galleries and Louisiana’s Trail in 2004. -

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo Chapter 1 Introduction This book is the result of research conducted for an exhibition on Louisiana history prepared by the Louisiana State Museum and presented within the walls of the historic Spanish Cabildo, constructed in the 1790s. All the words written for the exhibition script would not fit on those walls, however, so these pages augment that text. The exhibition presents a chronological and thematic view of Louisiana history from early contact between American Indians and Europeans through the era of Reconstruction. One of the main themes is the long history of ethnic and racial diversity that shaped Louisiana. Thus, the exhibition—and this book—are heavily social and economic, rather than political, in their subject matter. They incorporate the findings of the "new" social history to examine the everyday lives of "common folk" rather than concentrate solely upon the historical markers of "great white men." In this work I chose a topical, rather than a chronological, approach to Louisiana's history. Each chapter focuses on a particular subject such as recreation and leisure, disease and death, ethnicity and race, or education. In addition, individual chapters look at three major events in Louisiana history: the Battle of New Orleans, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Organization by topic allows the reader to peruse the entire work or look in depth only at subjects of special interest. For readers interested in learning even more about a particular topic, a list of additional readings follows each chapter. Before we journey into the social and economic past of Louisiana, let us look briefly at the state's political history. -

Houmas House Plantation and Gardens Beneath 200-Year-Old Live Oaks Dripping with Spanish Moss

LOUISIANA OFFICE OF TOURISM: CONTACT INFORMATION MEDIA Jay Tusa Research & Communications Director [email protected] 225.342.8142 TRAVEL TRADE Domestic Misty Shaw, APR, CDME Programs & Services Director [email protected] 225.219.9858 International Mike Prejean International Manager [email protected] 225.342.4354 STATEWIDE PROGRAM A NEW VACATION DESTINATION IS BREWING IN LOUISIANA. Beer lovers, rejoice! The fall of 2013 marked the launch of Louisiana’s Brewery Trail, a seven-stop exploration of the craft breweries that call Louisiana home. These breweries feature beers created with Louisiana’s food culture in mind—after all, what better to drink with a local dish than a local beer? The elder statesman of Louisiana’s craft breweries is Abita Brewing Company, which opened in 1986 in Abita Springs and is now the 14th-largest craft brewer in the nation. Rounding out the trail are Bayou Teche Brewing in Arnaudville, Chafunkta Brewing Company in Mandeville, Covington Brewhouse in Covington, NOLA Brewing Company in New Orleans, Parish Brewing Company in Broussard and Tin Roof Brewing Company in Baton Rouge. Each brewery on the trail allows guests to visit and sample its roster of beers, including pale ales, pilsners, strawberry beers and coffee porters. More breweries will be added soon. Check the site frequently for new experiences. Feeling thirsty? Get all the information you’ll need to set SHREVEPORT out on the Brewery Trail at www.LouisianaBrewTrail.com. HAMMOND BATON ROUGE COVINGTON ARNAUDVILLE MANDEVILLE BROUSSARD NEW ORLEANS STATEWIDE PROGRAM LOUISIANA’S AUDUBON GOLF TRAIL: 12 COURSES. 216 HOLES. 365 DAYS A YEAR. -

PPA Pre-Meeting Excursion: St Louis Cemetery I & Laura Plantation

PPA Pre-Meeting Excursion: St Louis Cemetery I & Laura Plantation Monday 17th April, 2017 9.30am – 5pm The PPA has organized a pre-meeting day trip to two of the key sites around New Orleans. We will start out at 9.30am and commence with small group guided tours of Saint Louis I Cemetery located in the Vieux Carre area of New Orleans. This will be followed by a tour of Laura Plantation and return to NO. St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 is one of three Roman Catholic cemeteries in NO. Of the three, it is the oldest (opened in 1789) and most famous. It is located just outside the French Quarter of NO. Most of the graves are in a maze of above-ground wall vaults, family tombs and society tombs, constructed in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was initially divided into sections for Catholics, non-Catholics, and “Negroes” (most probably slaves), and its location was chosen to avoid disease spreading to infect the living population. The cemetery contains the burials of many of the most illustrious citizens of New Orleans, including Etienne de Bore (pioneer in sugar development), Daniel Clark (financial supporter of the American Revolution), and Ernest "Dutch" Morial (the first African-American mayor of NO). Notable cemetery structures include the oven wall vaults, the supposed resting place of Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau in the Glapion family crypt, and tombs of French, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish society. The cemetery is on the US National Register of Historic Places. Views of St Louis Cemetery I Laura Plantation is a restored historic Louisiana Creole plantation on the west bank of the Mississippi River near Vacherie, Louisiana. -

Historic Natchitoches®

February 2015 300 years of flags that have ® flown over Natchitoches. HHistoricistoric NNatchitochesatchitoches A Free Guide to Leisure and Attractions Courtesy of The Natchitoches Times FRANCE 1714-1763 SPAIN 1763-1801 FRANCE 1801-1803 UNITED STATES 1803-61 CONFEDERATE STATES 1861-65 UNITED STATES 1960-PRESENT Don’t ever build STATE FLAG OF LOUISIANA something you haven’t dreamed of, first. STORY ON PAGE 3 STEEL MAGNOLIAS AND OTHER CITY OF NATCHITOCHES TOUR MAPS PAGES 7-10 Page 2 HISTORIC NATCHITOCHES February 2015 Inside...Inside... Mardi Gras Comes to Natchitoches .......................................................Page 4 En Plein air .......................................................Page 5 Welcome to Natchitoches: The Story of Melrose .......................................................Page 6 Enjoy your stay in our historic town Maps, Walking Tours, NSU Tour and Cane River Tour ................................................Pages 7-10 Basilica of the Immaculate Conception .....................................................Page 11 The Last Cavalry Horse .....................................................Page 12 Mary Belle de Vargus .....................................................Page 14 The Came Out of the Sky .....................................................Page 16 ‘Historic Natchitoches’ is a monthly publication of The Natchitoches Times To advertise in this publication contact The Natchitoches Times P.O. Box 448 Natchitoches, LA 71458 On the Cover George Olivier celebrates 50 years of business in Natchitoches. -

TRADITIONAL VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE in CREOLE NATCHITOCHES Natchitoches and Cane River, Louisiana

Packet Thursday, October 31 to Sunday, November 3, 2019 TRADITIONAL VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE IN CREOLE NATCHITOCHES Natchitoches and Cane River, Louisiana GREEK REVIVAL SPONSOR Natchitoches Historic District Development Commission CREOLE PLANTATION SPONSOR LIVE OAK SPONSOR RoyOMartin Foundation Regional Construction LLC SPECIAL PARTNERS Cane River National Heritage Area Natchitoches Events Center Natchitoches Convention & Visitors Bureau Natchitoches Service League HOST ORGANIZATIONS Institute of Classical Architecture & Art: Louisiana Chapter Louisiana Architectural Foundation National Center for Preservation Training & Technology Cane River Creole National Historical Park Follow us on social media! Traditional Vernacular Architecture in Creole Natchitoches 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 About the Hosts 4 Institute of Classical Architecture & Art (ICAA) - Louisiana Chapter Louisiana Architecture Foundation (LAF) National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT) Cane River Creole National Historical Park Registration 5 Accommodations: Chateau Saint Denis Hotel 6 Foray itinerary 7 Destinations 9 Fort St. Jean Baptiste State Historic Site Samuel Guy House (1850) National Center for Preservation Training & Technology (NCPTT) Louisiana State Museum and Sports Hall of Fame (2013) Rue Beauport Riverfront (2017) Natchitoches Historic District (1984) St. Augustine (Isle Brevelle) Catholic Church (1829) Badin-Roque House (1769-1785) Yucca (Melrose) Plantation (1794-1814) Oakland Plantation (c. 1790) Cherokee Plantation (1839) -

Improving Federal Agency Planning and Accountability Progress Report

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Park Cultural Resources Executive Order 13287, “Preserve America” Section 3: Improving Federal Agency Planning and Accountability Progress Report of the National Park Service September 30, 2017 Executive Order 13287, “Preserve America” Section 3: Improving Federal Agency Planning and Accountability Progress Report of the National Park Service September 30, 2017 Restoration work, Garden Key Light (aka, Tortuga Harbor Light), Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas National Park, Florida Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Historic Property Identification ....................................................................... 4 Chapter 2: Condition of Historic Properties ................................................................... 13 Chapter 3: Historic Property Stewardship ................................................................... 188 Chapter 4: Leasing of Historic Properties .................................................................... 277 CASE STUDY: US Forest Service Lease, Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Vancouver, Washington ................................................................................................ 29 Chapter 5: NPS Contribution to Local Economic Development ................................... 294 Chapter 6: Partnerships and the National Parks ......................................................... 357 CASE STUDY: -

Reviving the Old South: Piecing Together

REVIVING THE OLD SOUTH: PIECING TOGETHER THE HISTORY OF PLANTATION SITES Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University-San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of ARTS by Stacey Wilson, B.A. San Marcos, Texas August 2013 REVIVING THE OLD SOUTH: PIECING TOGETHER THE HISTORY OF PLANTATION SITES Committee Members Approved: _____________________________ Dwight Watson, Chair _____________________________ Patricia L. Denton _____________________________ Peter Dedek Approved: _____________________________ J. Michael Willoughby Dean of the Graduate College COPYRIGHT by Stacey Wilson 2013 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations From this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Stacey Wilson, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational purposes or scholarly purposes. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been completed without the support and encouragement from family and friends. I want to first thank Dr. Denton, Dr. Watson, and Dr. Dedek for agreeing to be on my committee and for helping me find a clear voice. I want to thank my sister for helping me proofread this thesis. She learned a lot more about Louisiana history than she ever thought she would. To my mom, stepfather, and a close network of friends that were there when I needed to vent about frustrations, to ease my mini meltdowns, and who listened when I needed to work out an idea…I want to say Thank you! This manuscript was submitted on Friday, June 21, 2013. -

National Heritage Areas

Charting a Future for National Heritage Areas A Report by the National Park System Advisory Board National Heritage Areas are places where natural, cultural, historic, and scenic resources combine to form a cohesive, nationally important landscape arising from patterns of human activity shaped by geography. These patterns make National Heritage Areas representative of the national experience through the physical features that remain and the traditions that have evolved in them. These regions are acknowledged by Congress for their capacity to tell nationally important stories about our nation. QUINEBAUG AND SHETUCKET RIVERS VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE CORRIDOR, LESLIE SWEETNAM; COVER PHOTO: BLACKSTONE RIVER VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA, SARAH LEEN Foreword In 004, the Director of the National Park Service asked the National Park System Advisory Board to review and report with recommendations on the appropriate role of the National Park Service in supporting National Heritage Areas. This is that report. The Board is a congressionally chartered body of twelve citizens appointed by the Secretary of the Interior. Established under the Historic Sites Act of 935, it is charged to provide advice on matters relating to operations in the parks and administration of the National Park Service. In preparing this report, the board sponsored meetings in four National Heritage Areas and consulted broadly with heritage area leaders, local and state-elected officials, community civic leaders and citizen groups, and National Park Service managers. National Heritage Areas represent a significant advance in conservation and historic preservation: large-scale, community-centered initiatives collaborating across political jurisdictions to protect nationally-important landscapes and living cultures. Managed locally, National Heritage Areas play a vital role in preserving the physical character, memories, and stories of our country, reminding us of our national origins and destiny. -

Final Dissertation Draft

Copyright by Miguel Edward Santos-Neves 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Miguel Edward Santos-Neves certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Reconfiguring Nation, Race, and Plantation Culture in Freyre and Faulkner Committee: Katherine Arens, Supervisor Wayne Lesser César Salgado Ivan Teixeira Alexandra Wettlaufer Reconfiguring Nation, Race, and Plantation Culture in Freyre and Faulkner by Miguel Edward Santos-Neves B.A.; M.A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication To my mother, father, Carolina, and Gabriel Acknowledgements “I would maintain that thanks are the highest form of thought… I would like to thank Katherine Arens for acting as the supervisor of my dissertation committee. She spent a great deal of time brainstorming with me over the course of this project, and she also helped me turn this dissertation into a sustained argument. She gave me the encouragement and the guidance to help me see this project through. I would like to thank Ivan Teixeira for the wonderful and affectionate friendship we have maintained over the years. Moreover, his commitment to the study of literature has been and will continue to be an inspiration to me. I would also like to show my dear appreciation to Wayne Lesser, César Salgado, and Alexandra Wettlaufer and for the careful attention they paid to my work and the insightful comments they made during my defense. The future of this manuscript will owe much to their contributions and suggestions.