Chapter 14 the Economics of Marine Litter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

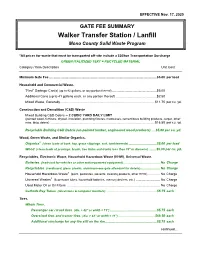

Rates 2017.Xlsx

Facilities with Scales - Schedule of Charges March 2017 Description Charges GENERAL Basic Gate Fee $50 per ton Minimum Gate Fee Charge for Waste $5.00 Recyclable Materials Drop Off No Charge TYPE OF MATERIAL HOUSEHOLD TRASH Up to 200 lbs. minimum Gate Fee $5.00 $0.50 each additional 20 lb. increment or fraction CONSTRUCTION AND DEMOLITION (C&D) C&D with no concrete, recyclables, green waste or chipable wood $50 per ton minimum $5.00 Separated Concrete $25 per ton minimum $5.00 Separated chipable wood $25 per ton minimum $5.00 Mixed C&D (household trash, recyclables, green waste and/or concrete in the load) $175 per ton minimum $5.00 GREEN WASTE Lawn Clippings/Leaves, Up to 400lbs. Minimum Gate Fee $5.00 yard waste, brush, shrubs, $.0.50 each additional 40lb. Increment or fraction trees, branches, woodchips. Tree Stumps $4.00 less than 24" plus Gate Fee $5.00 $12.00 greater than 24" plus Gate Fee $5.00 Mixed Debris (Green waste, household trash,recyclables and/or concrete in the load) $175 per ton minimum $5.00 ANIMALS Small (less than 25 lbs.) $5.00 each + $5.00 Gate Fee Medium (25-200 lbs.) $10.00 each + $5.00 Gate Fee Large (more than 200lbs.) $30.00 each + $5.00 Gate Fee FURNITURE $5.00 minimum Gate Fee plus $4.00 per item ELECTRONIC WASTE No Charge UNIVERSAL WASTE No Charge RESIDENTIAL HOUSEHOLD HAZARDOUS WASTE No Charge COMMERCIAL HAZARDOUS WASTE Not accepted SEPTAGE Inyo $65.00 first 3,000 gallons $42.00 per additional 1,000 gallons or increment Out of County $130.00 first $3,000 gallons $84.00 per addional 1,000 gallons or increment Facilities with Scales - Schedule of Charges March 2017 Description Charges TIRES Auto & light truck $4.00 for 19" rim or less + $5.00 Gate Fee $8.00 for 20" - 24.5" rim + $5.00 Gate Fee Tractor/Heavy Equipment Tire $30 For Up to 100 lbs + $5.00 Gate Fee $40 over 100 lbs. -

00 Gate Fee Schedule

EFFECTIVE Nov. 17, 2020 GATE FEE SUMMARY Walker Transfer Station / Lanfill Mono County Solid Waste Program *All prices for waste that must be transported off-site include a $20/ton Transportation Surcharge GREEN ITALICIZED TEXT = RECYCLED MATERIAL Category / Item Description Unit Cost Minimum Gate Fee ....................................................................................................................... $5.00 per load Household and Commercial Waste. “First” Garbage Can(s) (up to 82 gallons, or any portion thereof) .................................................. $5.00 Additional Cans (up to 41 gallons each, or any portion thereof) ............................................. $2.50 Mixed Waste, Generally ......................................................................................................... $11.75 per cu. yd. Construction and Demolition (C&D) Waste Mixed Building C&D Debris -- 2 CUBIC YARD DAILY LIMIT (painted wood, furniture, drywall, insulation, plumbing fixtures, mattresses, cementitious building products, carpet, other misc. bldg. debris) ..................................................................................................................... $16.50 per cu. yd. Recyclable Building C&D Debris (un-painted lumber, engineered wood products) …$5.00 per cu. yd. Wood, Green Waste, and Similar Organics. Organics8 (clean loads of bark, hay, grass clippings, sod, tumbleweeds) ............................... $5.00 per load Wood (clean loads of prunings, brush, tree limbs and trunks less than 18” -

Energy Recovery from Sewage Sludge: the Case Study of Croatia

energies Article Energy Recovery from Sewage Sludge: The Case Study of Croatia Dinko Đurđevi´c 1,* , Paolo Blecich 2 and Željko Juri´c 1 1 Energy Institute Hrvoje Požar, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Engineering, University of Rijeka, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 April 2019; Accepted: 16 May 2019; Published: 20 May 2019 Abstract: Croatia produced 21,366 tonnes of dry matter (DM) sewage sludge (SS) in 2016, a quantity expected to surpass 100,000 tonnes DM by 2024. Annual production rates for future wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) in Croatia are estimated at 5.8–7.3 Nm3/people equivalent (PE) for biogas and 20–25 kgDM/PE of sewage sludge. Biogas can be converted into 12–16 kWhel/PE of electricity and 19–24 kWhth/PE of heat, which is sufficient for 30–40% of electrical and 80–100% of thermal autonomy. The WWTP autonomy can be increased using energy recovery from sewage sludge incineration by 60% for electricity and 100% of thermal energy (10–13 kWhel/PE and 30–38 kWhth/PE). However, energy for sewage sludge drying exceeds energy recovery, unless solar drying is performed. 2 The annual solar drying potential is estimated between 450–750 kgDM/m of solar drying surface. The lower heating value of dried sewage sludge is 2–3 kWh/kgDM and this energy can be used for assisting sludge drying or for energy generation and supply to WWTPs. Sewage sludge can be considered a renewable energy source and its incineration generates substantially lower greenhouse gases emissions than energy generation from fossil fuels. -

Overview of Anaerobic Digestion for Municipal Solid Waste

Global Methane Initiative Overview of Anaerobic Digestion for Municipal Solid Waste Updated: October 2016 1 About This Presentation . Introduces the process of anaerobic digestion (AD) for municipal solid waste (MSW) . Provides an overview of anaerobic digestion microbiology . Helps you understand how you might benefit from AD . Guides you through the key areas to consider when developing an AD project . Reviews the status of AD globally and provides selected case studies Using Bookmarks to Navigate This presentation contains bookmarks to help you navigate. Using the panel on the left, click the bookmark to jump to the slide. For Chrome users, the bookmarks can be viewed by clicking on the bookmark icon ( ) at the top right of the screen. 2 Global Methane Initiative GMI is a voluntary, multilateral partnership that aims to reduce global methane emissions and to advance the abatement, recovery and use of methane as a valuable clean energy source. OBJECTIVES BENEFITS . Reduce anthropogenic methane . Decline in methane concentrations emissions and advance the and methane utilization will result recovery and use of methane in: while: – Sustainability – Enhancing economic growth – Energy security – Promoting energy security – Health and safety – Improving local air quality – Profitability and public health. 3 GMI Partners . Grew from 14 to 42 Partner governments, plus the European Commission . Accounts for nearly 70% of global anthropogenic methane emissions 4 Main Menu 1. Introduction – what is AD and why should it interest me? Click here for an introduction to AD 2. Is AD suitable for me? Click here for more info about the potential for AD 3. Step-by-step guide Click here for detailed information about the key issues to consider when developing an AD project 4. -

Biowaste Management in Europe Results of a Pre-Feasibility Report for a Facility for Organic Waste Recycling in South Backa Waste Management District - Serbia

Biowaste Management in Europe Results of a Pre-feasibility report for a facility for organic waste recycling in South Backa Waste Management District - Serbia Marco Ricci - Jürgensen Altereko sas on behalf Abt associates About myself • 20 years of experience in planning MSW management, designing and up¬grading of collection and transport schemes, assessing recycling facilities (focus on composting), planning comunication and participation initiatives, chairing multi-linguistic, multi-tasking working groups or projects. • 15 year foreign working experience as consulting expert focusing on issues related to solid waste management. Extensive consultancy experience in the Solid Waste Sector – on Strategy and Policy, Fees&Taxes, Separate collection schemes - , both in ´advanced´ and ´low to middle income’ countries in Europe, Latin America and Asia. • 10 years experience cooperating with international organisation/agencies (as ECN-European Compost Network, ACRR, EEA- European Environment Agency, Sweepnet-GIZ, SCOW). About myself About myself CIC Italian Composting and Biogas Association Senior Expert www.compost.it ISWA International Solid Waste Association Chair of the Working Group on Biological Treatment of Waste www.iswa.org Ecomondo International Fair Ambassador en.ecomondo.com Activities (outside Italy) Bulgaria Czech Republic Slovak Republic UK Spain Tunisia/Sweep-Net Brazil Cambodia Chile Overview • What is biowaste? • Biological treatment options • From City Assessment to Pre-feasibility investigations • South Backa WMR – scenarios -

Full Scale Co-Digestion of Wastewater Sludge and Food Waste: Bottlenecks and Possibilities

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Engineering and Information Faculty of Engineering and Information Sciences - Papers: Part A Sciences 1-1-2017 Full scale co-digestion of wastewater sludge and food waste: bottlenecks and possibilities Long D. Nghiem University of Wollongong, Technical University of Munich, [email protected] Konrad Koch Technische Universitat Munchen, [email protected] David Bolzonella University of Verona Jörg E. Drewes Technical University of Munich, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/eispapers Part of the Engineering Commons, and the Science and Technology Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nghiem, Long D.; Koch, Konrad; Bolzonella, David; and Drewes, Jörg E., "Full scale co-digestion of wastewater sludge and food waste: bottlenecks and possibilities" (2017). Faculty of Engineering and Information Sciences - Papers: Part A. 6423. https://ro.uow.edu.au/eispapers/6423 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Full scale co-digestion of wastewater sludge and food waste: bottlenecks and possibilities Abstract Wastewater treatment plants in many countries use anaerobic digesters for biosolids management and biogas generation. Opportunities exist to utilise the spare capacity of these digesters to co-digest food waste and sludge for energy recovery and a range of other economic and environmental benefits. This paper provides a critical perspective for full-scale implementation of co-digestion of food waste and wastewater sludge. Data compiled from full-scale facilities and the peer-reviewed literature revealed several key bottlenecks hindering full-scale implementation of co-digestion. -

Organic Waste Economic Values Analysis Summary Report

Environment Protection Authority Consultancy report: Organic waste economic values analysis Summary report This report has been prepared by consultants for the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) and the views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the EPA. The EPA cannot guarantee the accuracy of the report, and does not accept liability for any loss or damage incurred as a result of relying on its accuracy. Department of Industry and Trade Environment Protection Agency ORGANIC WASTE ECONOMIC VALUES ANALYSIS SUMMARY REPORT January, 2002 Prepared in association with Access Economics Ref: 3091-01 NOLAN-ITU Pty Ltd ACN 067 785 853 ABN 23 359 240 890 P.O. Box 393 Level 1, 625 High St, East Kew Victoria 3102 Telephone: (03) 9859 3344 Facsimile: (03) 9859 3411 NOLAN-ITU PTY LTD ACN 067 785 853 ABN 23 359 240 890 Melbourne PO Box 393 Level 1, 625 High Street East Kew VIC 3102 Tel: (03) 9859 3344 Fax: (03) 9859 3411 Copyright © Nolan-ITU Pty Ltd 2002 This document is and shall remain the property of Nolan-ITU Pty Ltd. The document may only be used for the purpose for which it was commissioned and in accordance with the terms of engagement for the commission. Unauthorised use of this document in any form whatsoever is prohibited.© Printed on Recycled Paper REF: 3091-01 Document Issue and Status Rev. Status Date Project Manager Reviewer 1-0 Preliminary Draft 18 July 2001 John Nolan Bruno Schacher 1-1 Internal Draft 19 July 2001 John Nolan Sam Bateman 1-2 Draft 10 August 2001 John Nolan Sam Bateman 1-4 Final Draft 13 November 2001 John Nolan Sam Bateman 1-5 Final Draft No. -

INTEGRATED SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT for LOCAL GOVERNMENTS a Practical Guide

INTEGRATED SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENTS A Practical Guide Improving solid waste management is crucial for countering public health impacts of uncollected waste and environmental impacts of open dumping and burning. This practical reference guide introduces key concepts of integrated solid waste management and identifi es crosscutting issues in the sector, derived mainly from fi eld experience in the technical assistance project Mainstreaming Integrated Solid Waste Management in Asia. This guide contains over 40 practice briefs covering solid waste management planning, waste categories, waste containers and collection, waste processing and diversion, landfi ll development, landfi ll operations, and contract issues. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacifi c region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to a large share of the world’s poor. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by members, including from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. INTEGRATED SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENTS A Practical Guide ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines 9 789292 578374 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK www.adb.org Tool Kit for Solid Waste Management in Asian_COVER.indd 1 6/1/2017 5:14:11 PM INTEGRATED SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENTS A Practical Guide Improving solid waste management is crucial for countering the public health impacts of uncollected waste as well as the environmental impacts of open dumping and burning. -

Annex E – Approach to Costs

Imagine the result FINAL REPORT ASSESSMENT OF THE OPTIONS TO IMPROVE THE MANAGEMENT OF BIO-WASTE IN THE EUROPEAN UNION ANNEX E: Approach to estimating costs STUDY CONTRACT NR 07.0307/2008/517621/ETU/G4 EUROPEAN COMMISSION DG ENVIRONMENT ARCADIS Project number – 11/004759 | Version A | 30-11-2009 2/57 11/004759 CLIENT European Commission Directorate-General Environment Mr. Bartosz Zambrzycki Unit G.4 – BU – 5 05/118 B-1049 Brussels ASSESSMENT OF THE OPTIONS TO IMPROVE THE MANAGEMENT OF BIO-WASTE IN THE EUROPEAN UNION CONSULTANTS ARCADIS Belgium nv Clara Snellingsstraat 27 2100 Deurne Belgium EUNOMIA Research & Consulting 62 Queen square Bristol, BS1 4JZ United Kingdom Contact Laurent Franckx Telephone +32 3 328 62 73 Telefax +32 3 328 62 87 E-mail l.franckx @arcadisbelgium.be Website www.arcadisbelgium.be Assessment of the options to improve the management of biowaste in the European Union – Annex E: Approach to estimating costs 3/57 11/004759 Revision Version Date Remark Final 30/11/2009 Issued by Department Function Name Signature Date ARCADIS, Team leader and Laurent Franckx Strategic Policy senior economist Advice ARCADIS, Senior waste Mike Van Acoleyen Strategic Policy specialist Advice Eunomia Dr Dominic Hogg Eunomia Dr Adrian Gibbs Eunomia Tim Elliott Eunomia Chris Sherrington Eunomia Ann Ballinger Eunomia Siobhan O’Brien Eunomia Debbie Lister Eunomia Catherine Beswick Verified by Department Function Name Signature Date Approval by client Department Function Name Signature Date Assessment of the options to improve the management -

Proof of Concept of High-Rate Decentralized Pre-Composting of Kitchen Waste: Optimizing Design and Operation of a Novel Drum Reactor

Waste Management 91 (2019) 20–32 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Waste Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wasman Proof of concept of high-rate decentralized pre-composting of kitchen waste: Optimizing design and operation of a novel drum reactor Myrsini Sakarika a, Marc Spiller a, Robin Baetens b, Gil Donies a, Jolan Vanderstuyf c, Kathleen Vinck d, ⇑ Karl C. Vrancken a,e, Gregory Van Barel d, Els Du Bois c, Siegfried E. Vlaeminck a, a Research Group of Sustainable Air, Energy and Water Technology, Department of Bioscience Engineering, University of Antwerp, Groenenborgerlaan 171, 2020 Antwerpen, Belgium b Energy and Materials in Infrastructure and Buildings (EMIB) Group, Department of Electromechanics, University of Antwerp, Groenenborgerlaan 171, 2020 Antwerpen, Belgium c Optical Metrology, 3D Design and Mechanics (Op3Mech) Group, Department of Electromechanics, University of Antwerp, Groenenborgerlaan 171, 2020 Antwerpen, Belgium d Product Development Group, Department of Product Development, University of Antwerp, Ambtmanstraat 1, 2000 Antwerpen, Belgium e VITO, Boeretang 200, 2400 Mol, Belgium article info abstract Article history: Each ton of organic household waste that is collected, transported and composted incurs costs (€75/ton Received 10 January 2019 gate fee). Reducing the mass and volume of kitchen waste (KW) at the point of collection can diminish Revised 29 March 2019 transport requirements and associated costs, while also leading to an overall reduction in gate fees for Accepted 23 April 2019 final processing. To this end, the objective of this research was to deliver a proof of concept for the so- Available online 29 April 2019 called ‘‘urban pre-composter”; a bioreactor for the decentralized, high-rate pre-treatment of KW, that aims at mass and volume reduction at the point of collection. -

Waste Management Services 2013

Waste Management Services 2013 The OECD Competition Committee debated Waste Management Services in October 2013. This document includes an executive summary of that debate and the documents from the meeting: a background note, written submissions by Canada, the Czech Republic, Estonia, the European Union, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Peru, Poland, Romania, the Russian Federation, the Slovak Republic, South Africa, Sweden, Chinese Taipei, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, the United States, BIAC as well as an aide-memoire of the discussion. Technological and policy changes have altered the economics of waste collection and treatment. Landfills are further away from cities and larger. More waste is diverted towards treatments that allow to re-use it, recycle it, or to recover energy from it. Secondary raw materials derived from recycled waste are being increasingly sought afters, as primary raw materials are becoming scarcer and more expensive. Producers have been made responsible for the products they have put on the market at the post-consumer stage of the products’ life. All these changes are raising new competition issues, some relative to the conduct of firms operating in the markets for the management of waste, some raised by the ever-increasing amount of environmental legislation. This legislation is aimed at protecting the environment and the health of citizens, but may sometimes raise unnecessary barriers to competition and thus reduce the incentives towards efficiency. This Roundtable examines recent developments in the management of municipal solid waste and discusses the experience of competition agencies in addressing the competition implications of these changes. -

Towards a Circular Economy – Waste Management in the EU

Towards a circular economy – Waste management in the EU STUDY Science and Technology Options Assessment EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service Scientific Foresight Unit (STOA) PE 581.913 Towards a circular economy - Waste management in the EU Study IP/G/STOA/FWC/2013-001/LOT 3/C3 September 2017 Abstract This report examines the role of waste management in the context of a circular economy transition. Key challenges relate to moving beyond the perception of ‘waste as a problem’ to ‘waste as a resource’. To this end high levels of cooperation are needed between the waste industry and enterprises engaged in circular economy business models. Collecting high quality waste streams for re-use, remanufacturing and recycling also requires citizen engagement and integrated infrastructure development from the municipal to the EU level. Ultimately, both waste prevention as well as a widespread growth in circular economy activities will require a coherent and holistic approach that takes recovery options into account at every stage of the product life cycle. Co-benefits will include reducing environmental burden as well as creating both high-skilled and low-skilled jobs for an inclusive, green economy. In concrete terms, this report examines five waste streams identified in the EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan: municipal waste, packaging waste, food waste, bio-waste and critical raw materials. It looks at the current state of policy development, presents trends and data comparing Member State performance, reviews the state of technological development, and assesses employment opportunities relevant to each waste stream in the overarching context of assessing progress toward the circular economy transition in the EU.