Energy Recovery from Sewage Sludge: the Case Study of Croatia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislation for the Reuse of Biosolids on Agricultural Land in Europe: Overview

sustainability Review Legislation for the Reuse of Biosolids on Agricultural Land in Europe: Overview Maria Cristina Collivignarelli 1 , Alessandro Abbà 2, Andrea Frattarola 1, Marco Carnevale Miino 1 , Sergio Padovani 3, Ioannis Katsoyiannis 4,* and Vincenzo Torretta 5 1 Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering, University of Pavia, via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (M.C.C.); [email protected] (A.F.); [email protected] (M.C.M.) 2 Department of Civil, Environmental, Architectural Engineering and Mathematics, University of Brescia, via Branze 43, 25123 Brescia, Italy; [email protected] 3 ARPA Lombardia, Pavia Department, via Nino Bixio 13, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Chemistry, Laboratory of Chemical and Environmental Technology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece 5 Department of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, University of Insubria, via G.B. Vico 46, 21100 Varese, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 September 2019; Accepted: 25 October 2019; Published: 29 October 2019 Abstract: The issues concerning the management of sewage sludge produced in wastewater treatment plants are becoming more important in Europe due to: (i) the modification of sludge quality (biological and chemical sludge are often mixed with negative impacts on sludge management, especially for land application); (ii) the evolution of legislation (landfill disposal is banned in many European countries); and (iii) the technologies for energy and material recovery from sludge not being fully applied in all European Member States. Furthermore, Directive 2018/851/EC introduced the waste hierarchy that involved a new strategy with the prevention in waste production and the minimization of landfill disposal. -

Use of a Water Treatment Sludge in a Sewage Sludge Dewatering Process

E3S Web of Conferences 30, 02006 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20183002006 Water, Wastewater and Energy in Smart Cities Use of a water treatment sludge in a sewage sludge dewatering process Justyna Górka1,*, Małgorzata Cimochowicz-Rybicka1 , and Małgorzata Kryłów1 1 University of Technology, Department of Environmental Engineering, 24 Warszawska, Cracow 31- 155, Poland Abstract. The objective of the research study was to determine whether a sewage sludge conditioning had any impact on sludge dewaterability. As a conditioning agent a water treatment sludge was used, which was mixed with a sewage sludge before a digestion process. The capillary suction time (CST) and the specific filtration resistance (SRF) were the measures used to determine the effects of a water sludge addition on a dewatering process. Based on the CST curves the water sludge dose of 0.3 g total volatile solids (TVS) per 1.0 g TVS of a sewage sludge was selected. Once the water treatment sludge dose was accepted, disintegration of the water treatment sludge was performed and its dewaterability was determined. The studies have shown that sludge dewaterability was much better after its conditioning with a water sludge as well as after disintegration and conditioning, if comparing to sludge with no conditioning. Nevertheless, these findings are of preliminary nature and future studies will be needed to investigate this topic. 1 Introduction Dewatering of sludge is a very important stage of the sludge processing. It reduces both sludge mass and volume, which consequently reduces costs of a further sludge processing, facilitates its transport and allows for its thermal processing. -

A Novel Waste Water Treatment Plant for the Disposal of Organic Waste from Mobile Toilets

A Novel Waste Water Treatment Plant for The Disposal of Organic Waste from Mobile Toilets A Novel Waste Water Treatment Plant for The Disposal of Organic Waste from Mobile Toilets G. BONIFAZI, R. GASBARRONE, R. PALMIERI, G. CAPOBIANCO, S. SERRANTI Departments of Medical Sciences and Biotechnologies and of Chemical Eng. Materials, Environment- Sapienza University of Rome, Abstract The EU wastewater management industry is continuously looking for innovative technological solutions that can enter the market with a reduced environmental impact. This paper focuses on the problems associated to the disposal of human waste and on the specific market of the so-called mobile toilets. These are independent portable units equipped with sanitary tools that use chemical agents to disinfect the vessel and not connected to the sewer network. With growing awareness towards effective sanitation, mobile toilets have gained immense popularity in recent years and are now widely used at construction sites, event venues, public places, and in several other application like temporary refugee housing, migrants’ camps, military missions, cases of natural disasters, airplanes, trains, campers, caravans and campsites. This paper illustrates a new process for the disposal of organic waste from mobile toilets. Keywords: Waste Water Treatment Plants, Chemical Portable Toilets, Use of sludges in agriculture. 1. Introduction into surface and ground water and to avoid toxic effects on soil, plants, animals and humans. In The use of sludge in agriculture within the EU is most cases, national authorities have currently regulated only by the limits of heavy implemented policies supporting the use of metals (Cd, Cu, Hg, Ni, Pb and Zn) listed in sludge in agriculture, as it is considered to be the Council Directive 86/278/EEC. -

Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture: Good Practice Examples

SAFE USE OF WASTEWATER IN AGRICULTURE: GOOD PRACTICE EXAMPLES Hiroshan Hettiarachchi Reza Ardakanian, Editors SAFE USE OF WASTEWATER IN AGRICULTURE: GOOD PRACTICE EXAMPLES Hiroshan Hettiarachchi Reza Ardakanian, Editors PREFACE Population growth, rapid urbanisation, more water intense consumption patterns and climate change are intensifying the pressure on freshwater resources. The increasing scarcity of water, combined with other factors such as energy and fertilizers, is driving millions of farmers and other entrepreneurs to make use of wastewater. Wastewater reuse is an excellent example that naturally explains the importance of integrated management of water, soil and waste, which we define as the Nexus While the information in this book are generally believed to be true and accurate at the approach. The process begins in the waste sector, but the selection of date of publication, the editors and the publisher cannot accept any legal responsibility for the correct management model can make it relevant and important to any errors or omissions that may be made. The publisher makes no warranty, expressed or the water and soil as well. Over 20 million hectares of land are currently implied, with respect to the material contained herein. known to be irrigated with wastewater. This is interesting, but the The opinions expressed in this book are those of the Case Authors. Their inclusion in this alarming fact is that a greater percentage of this practice is not based book does not imply endorsement by the United Nations University. on any scientific criterion that ensures the “safe use” of wastewater. In order to address the technical, institutional, and policy challenges of safe water reuse, developing countries and countries in transition need clear institutional arrangements and more skilled human resources, United Nations University Institute for Integrated with a sound understanding of the opportunities and potential risks of Management of Material Fluxes and of Resources wastewater use. -

Rates 2017.Xlsx

Facilities with Scales - Schedule of Charges March 2017 Description Charges GENERAL Basic Gate Fee $50 per ton Minimum Gate Fee Charge for Waste $5.00 Recyclable Materials Drop Off No Charge TYPE OF MATERIAL HOUSEHOLD TRASH Up to 200 lbs. minimum Gate Fee $5.00 $0.50 each additional 20 lb. increment or fraction CONSTRUCTION AND DEMOLITION (C&D) C&D with no concrete, recyclables, green waste or chipable wood $50 per ton minimum $5.00 Separated Concrete $25 per ton minimum $5.00 Separated chipable wood $25 per ton minimum $5.00 Mixed C&D (household trash, recyclables, green waste and/or concrete in the load) $175 per ton minimum $5.00 GREEN WASTE Lawn Clippings/Leaves, Up to 400lbs. Minimum Gate Fee $5.00 yard waste, brush, shrubs, $.0.50 each additional 40lb. Increment or fraction trees, branches, woodchips. Tree Stumps $4.00 less than 24" plus Gate Fee $5.00 $12.00 greater than 24" plus Gate Fee $5.00 Mixed Debris (Green waste, household trash,recyclables and/or concrete in the load) $175 per ton minimum $5.00 ANIMALS Small (less than 25 lbs.) $5.00 each + $5.00 Gate Fee Medium (25-200 lbs.) $10.00 each + $5.00 Gate Fee Large (more than 200lbs.) $30.00 each + $5.00 Gate Fee FURNITURE $5.00 minimum Gate Fee plus $4.00 per item ELECTRONIC WASTE No Charge UNIVERSAL WASTE No Charge RESIDENTIAL HOUSEHOLD HAZARDOUS WASTE No Charge COMMERCIAL HAZARDOUS WASTE Not accepted SEPTAGE Inyo $65.00 first 3,000 gallons $42.00 per additional 1,000 gallons or increment Out of County $130.00 first $3,000 gallons $84.00 per addional 1,000 gallons or increment Facilities with Scales - Schedule of Charges March 2017 Description Charges TIRES Auto & light truck $4.00 for 19" rim or less + $5.00 Gate Fee $8.00 for 20" - 24.5" rim + $5.00 Gate Fee Tractor/Heavy Equipment Tire $30 For Up to 100 lbs + $5.00 Gate Fee $40 over 100 lbs. -

Five Facts About Incineration Five Facts About Incineration

Five facts about incineration Five facts about incineration Across the globe, cities are looking for ways to improve their municipal solid waste systems. In the search for services that are affordable, green and easy to implement, many cities are encouraged to turn to waste-to-energy (WtE) technologies, such as incineration.1 But, as found in WIEGO’s Technical Brief 11 (Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: A Technical Guide on Waste-to-Energy Initiatives by Jeroen IJgosse), incineration is far from the perfect solution and, particularly in the Global South, can be less cost-effective, more complicated and can negatively impact the environment and informal waste workers’ livelihoods. Below, we have collected the top five issues highlighted in the study that show why this technology is a risky choice: 1. Incineration costs more than recycling. How incineration may be promoted: Incineration is a good economic decision because it reduces the costs associated with landfill operations while also creating energy that can be used by the community. The reality: • In 2016, the World Energy Council reported that, “energy generation from waste is a costly option, in comparison with other established power generation sources.” • Setting up an incineration project requires steep investment costs from the municipality. • For incineration projects to remain financially stable long-term, high fees are required, which place a burden on municipal finances and lead to sharp increases in user fees. • If incinerators are not able to collect enough burnable waste, they will burn other fuels (gas) instead. Contract obligations can force a municipality to make up the difference if an incinerator doesn’t burn enough to create the needed amount of energy. -

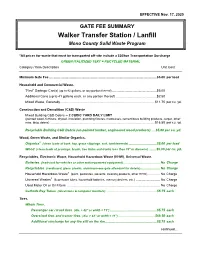

00 Gate Fee Schedule

EFFECTIVE Nov. 17, 2020 GATE FEE SUMMARY Walker Transfer Station / Lanfill Mono County Solid Waste Program *All prices for waste that must be transported off-site include a $20/ton Transportation Surcharge GREEN ITALICIZED TEXT = RECYCLED MATERIAL Category / Item Description Unit Cost Minimum Gate Fee ....................................................................................................................... $5.00 per load Household and Commercial Waste. “First” Garbage Can(s) (up to 82 gallons, or any portion thereof) .................................................. $5.00 Additional Cans (up to 41 gallons each, or any portion thereof) ............................................. $2.50 Mixed Waste, Generally ......................................................................................................... $11.75 per cu. yd. Construction and Demolition (C&D) Waste Mixed Building C&D Debris -- 2 CUBIC YARD DAILY LIMIT (painted wood, furniture, drywall, insulation, plumbing fixtures, mattresses, cementitious building products, carpet, other misc. bldg. debris) ..................................................................................................................... $16.50 per cu. yd. Recyclable Building C&D Debris (un-painted lumber, engineered wood products) …$5.00 per cu. yd. Wood, Green Waste, and Similar Organics. Organics8 (clean loads of bark, hay, grass clippings, sod, tumbleweeds) ............................... $5.00 per load Wood (clean loads of prunings, brush, tree limbs and trunks less than 18” -

Chapter 14 the Economics of Marine Litter

Chapter 14 The Economics of Marine Litter Stephanie Newman, Emma Watkins, Andrew Farmer, Patrick ten Brink and Jean-Pierre Schweitzer Abstract This chapter aims to provide an overview of research into quantifying the economic impacts of marine litter. From an environmental economics perspec- tive it introduces the difficulties in measuring the economic costs of marine litter; reviews those sectors where these costs are notable; and considers policy instru- ments, which can reduce these costs. Marine litter is underpinned by dynamic and complex processes, the drivers and impacts of which are multi-scalar, trans- boundary, and play out in both marine and terrestrial environments. These impacts include economic costs to expenditure, welfare and lost revenue. In most cases, these are not borne by the producers or the polluters. In industries such as fisher- ies and tourism the costs of marine litter are beginning to be quantified and are considerable. In other areas such as impacts on human health, or more intangible costs related to reduced ecosystem services, more research is evidently needed. As the costs of marine litter are most often used to cover removing debris or recov- ering from the damage which they have caused, this expenditure represents treat- ment rather than cure, and although probably cheaper than inaction do not present a strategy for cost reduction. Economic instruments, such as taxes and charges addressing the drivers of waste, for instance those being developed for plastic bags, could be used to reduce the production of marine litter and minimise its impacts. In any case, there remain big gaps in our understanding of the harm caused by marine litter, which presents difficulties when attempting to both quantify its economic costs, and develop effective and efficient instruments to reduce them. -

2.2 Sewage Sludge Incineration

2.2 Sewage Sludge Incineration There are approximately 170 sewage sludge incineration (SSI) plants in operation in the United States. Three main types of incinerators are used: multiple hearth, fluidized bed, and electric infrared. Some sludge is co-fired with municipal solid waste in combustors based on refuse combustion technology (see Section 2.1). Refuse co-fired with sludge in combustors based on sludge incinerating technology is limited to multiple hearth incinerators only. Over 80 percent of the identified operating sludge incinerators are of the multiple hearth design. About 15 percent are fluidized bed combustors and 3 percent are electric. The remaining combustors co-fire refuse with sludge. Most sludge incinerators are located in the Eastern United States, though there are a significant number on the West Coast. New York has the largest number of facilities with 33. Pennsylvania and Michigan have the next-largest numbers of facilities with 21 and 19 sites, respectively. Sewage sludge incinerator emissions are currently regulated under 40 CFR Part 60, Subpart O and 40 CFR Part 61, Subparts C and E. Subpart O in Part 60 establishes a New Source Performance Standard for particulate matter. Subparts C and E of Part 61--National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP)--establish emission limits for beryllium and mercury, respectively. In 1989, technical standards for the use and disposal of sewage sludge were proposed as 40 CFR Part 503, under authority of Section 405 of the Clean Water Act. Subpart G of this proposed Part 503 proposes to establish national emission limits for arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, chromium, lead, mercury, nickel, and total hydrocarbons from sewage sludge incinerators. -

Mobility of Heavy Metals in Municipal Sewage Sludge from Different Throughput Sewage Treatment Plants

Pol. J. Environ. Stud. Vol. 21, No. 6 (2012), 1603-1611 Original Research Mobility of Heavy Metals in Municipal Sewage Sludge from Different Throughput Sewage Treatment Plants Jarosław Gawdzik1*, Barbara Gawdzik2** 1Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Kielce University of Technology, Division of Waste Management, Al. 1000-lecia Państwa Polskiego 7, 25-314 Kielce, Poland 2Institute of Chemistry, Faculty of Mathematics and Science, Jan Kochanowski University of Humanities and Sciences, Świętokrzyska 15, 25-406 Kielce, Poland Received: 27 June 2011 Accepted: 11 May 2012 Abstract Sewage sludge heavy metals can be dissolved, precipitated, co-precipitated with metal oxides, and adsorbed or associated on the particles in biological debris. Heavy metals are found in the form of oxides, hydroxides, sulphides, sulphates, phosphates, silicates, organic bindings forming complexes with humic com- pounds, and complex sugars. Polish regulations specifying the maximum levels of heavy metals in municipal sewage sludge used for agricultural purposes refer to the total content of lead, cadmium, mercury, nickel, zinc, copper, and chromium. The aim of our study was to evaluate the mobility of heavy metals in sewage sludge from wastewater treatment plants in Świętokrzyskie Province. Stabilized sewage sludge from wastewater treatment was ana- lyzed in accordance with the extraction method proposed by the Community Bureau of Reference (BCR). Zinc, cadmium, lead, and nickel were determined by means of the standard addition with the use of a Perkin-Elmer 3100-BG FAAS atomic absorption spectrophotometer. Chromium and copper were tested using the FAAS technique. The sequence analysis revealed the presence of heavy metals in all fractions (F-I, F-II, F-III, F-IV). -

Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture Safe Use of Safe Wastewater in Agriculture Proceedings No

A UN-Water project with the following members and partners: UNU-INWEH Proceedings of the UN-Water project on the Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture Wastewater Safe of Use Proceedings No. 11 No. Proceedings | UNW-DPC Publication SeriesUNW-DPC Coordinated by the UN-Water Decade Programme on Capacity Development (UNW-DPC) Editors: Jens Liebe, Reza Ardakanian Editors: Jens Liebe, Reza Ardakanian (UNW-DPC) Compiling Assistant: Henrik Bours (UNW-DPC) Graphic Design: Katja Cloud (UNW-DPC) Copy Editor: Lis Mullin Bernhardt (UNW-DPC) Cover Photo: Untited Nations University/UNW-DPC UN-Water Decade Programme on Capacity Development (UNW-DPC) United Nations University UN Campus Platz der Vereinten Nationen 1 53113 Bonn Germany Tel +49-228-815-0652 Fax +49-228-815-0655 www.unwater.unu.edu [email protected] All rights reserved. Publication does not imply endorsement. This publication was printed and bound in Germany on FSC certified paper. Proceedings Series No. 11 Published by UNW-DPC, Bonn, Germany August 2013 © UNW-DPC, 2013 Disclaimer The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the agencies cooperating in this project. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the UN, UNW-DPC or UNU concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Unless otherwise indicated, the ideas and opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent the views of their employers. -

The Global E-Waste Monitor 2020 Quantities, Flows, and the Circular Economy Potential

The Global E-waste Monitor 2020 Quantities, flows, and the circular economy potential Authors: Vanessa Forti, Cornelis Peter Baldé, Ruediger Kuehr, Garam Bel Contributions by: S. Adrian, M. Brune Drisse, Y. Cheng, L. Devia, O. Deubzer, F. Goldizen, J. Gorman, S. Herat, S. Honda, G. Iattoni, W. Jingwei, L. Jinhui, D.S. Khetriwal, J. Linnell, F. Magalini, I.C. Nnororm, P. Onianwa, D. Ott, A. Ramola, U. Silva, R. Stillhart, D. Tillekeratne, V. Van Straalen, M. Wagner, T. Yamamoto, X. Zeng Supporting Contributors: 2 The Global E-waste Monitor 2020 Quantities, flows, and the circular economy potential Authors: Vanessa Forti, Cornelis Peter Baldé, Ruediger Kuehr, Garam Bel Contributions by: S. Adrian, M. Brune Drisse, Y. Cheng, L. Devia, O. Deubzer, F. Goldizen, J. Gorman, S. Herat, S. Honda, G. Iattoni, W. Jingwei, L. Jinhui, D.S. Khetriwal, J. Linnell, F. Magalini, I.C. Nnororm, P. Onianwa, D. Ott, A. Ramola, U. Silva, R. Stillhart, D. Tillekeratne, V. Van Straalen, M. Wagner, T. Yamamoto, X. Zeng 3 Copyright and publication information 4 Contact information: Established in 1865, ITU is the intergovernmental body responsible for coordinating the For enquiries, please contact the corresponding author C.P. Baldé via [email protected]. shared global use of the radio spectrum, promoting international cooperation in assigning satellite orbits, improving communication infrastructure in the developing world, and Please cite this publication as: establishing the worldwide standards that foster seamless interconnection of a vast range of Forti V., Baldé C.P., Kuehr R., Bel G. The Global E-waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, communications systems. From broadband networks to cutting-edge wireless technologies, flows and the circular economy potential.