Analysis of Nordic Regulatory Framework and Its Effect on Waste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fortum Recycling & Waste

Fortum Recycling & Waste Public affair priorities 06/2021 Fortum Recycling & Waste Public affair priorities FORTUM RECYCLING & WASTE Public affair priorities As part of Fortum corporation, our Recycling & Waste business area leads the change towards a low-emission energy system and the optimal use of resources. Our goal is to support our customers’ businesses by conserving natural resources and promoting a circular economy. We work together with our customers to build smart and sustainable solutions to ensure the circulation of valuable materials and the removal of harmful substances from the material cycle. Fortum Recycling & Waste employs approximately 650 employees in about 30 offices and treatment centers in Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Norway. Megatrends like climate change, urbanisation, population growth and limited natural resources are shaping the world. They are pushing us to maximise the efficient use of resources. Reliable waste management and resource efficiency are fundamental in a society based on sustainable practices for a cleaner world. Our aim is to promote the transition towards a more extensive circular economy. For us, a successful circular economy means that materials are recycled as much as possible and hazardous substances are removed from circulation. Our circular economy approach receives, processes and reuses customer waste for material recycling and energy production. Policy objectives should aim to ensure a clean circular economy model and a stronger market for high-quality recycled raw materials. Ultimately, Fortum’s aim is for as much of the waste stream as possible to be recycled, recovered or reused. Waste that is unsuitable for recycling or reuse is incinerated in waste-to-energy plants or in dedicated plants for hazardous waste. -

Perceived Value Influencing the Household Waste Sorting

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Perceived Value Influencing the Household Waste Sorting Behaviors in Rural China Ying Ma 1,2, Mansoor Ahmed Koondhar 1, Shengke Liu 1, Huiling Wang 1 and Rong Kong 1,* 1 School of Economics and Management, Northwest A&F University, No. 3 Taicheng Road, Yangling 712100, China; [email protected] (Y.M.); [email protected] (M.A.K.); [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (H.W.) 2 School of Economics and Management, Xi’an Shiyou University, No. 18 Dianzi Road, Xi’an 710065, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 July 2020; Accepted: 19 August 2020; Published: 21 August 2020 Abstract: Waste sorting is the cardinal measurement to solve the problem of low efficiency of rural environmental governance and to alleviate environmental pollution by reduction, recycling, and harmlessness in rural areas. However, non-excludable and non-rival features of public goods easily cause a wide free-rider problem, which results in a low frequency of participation in the waste sorting of rural people. Based on the theory of the utility maximization of the rational economic man, this paper investigates survey data of 688 farm households in three cities and three counties of Shaanxi Province to explore the effect of the perceived value on the household waste classification behavior based on cost-benefit analysis. The results show that perceived benefit and perceived cost are important perceived value factors affecting farmers’ participation in waste sorting. Specifically, the spiritual benefit of the perceived benefit has a significantly positive impact on classification behavior, while the time cost, physical cost, and material cost of the perceived cost have a negative impact on waste classification behavior. -

EU Sustainability Legislation on Batteries: Batteries Directive Revision RECHARGE Comments to EU Commission Stakeholder Consultation from April 27 to May 5, 2020

EU Sustainability Legislation on Batteries: Batteries Directive revision RECHARGE Comments to EU Commission stakeholder consultation from April 27 to May 5, 2020 EU Sustainability Legislation on Batteries: Batteries Directive I 2 EU SUSTAINABILITY LEGISLATION ON BATTERIES In October 2017, the European Commission launched the EU Batteries Alliance to create a competitive and sustainable battery manufacturing activity in the European Union, contributing to both growth and sustainability objectives. In parallel, the Commission has initiated the review of Directive 2006/66/EC (the “Batteries Directive”). Under the EU Sustainability Legislation on Batteries initiative, the Commission intends to complement the existing legislation with key sustainability measures as set out by the European Green Deal, and the respective Industrial Strategy, Circular Economy Action Plan and Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability. By the end of 2020, the Commission will publish a proposal for a new battery legislation. The improved regulatory framework for batteries will be pivotal to address the high goal of establishing a sustainable battery industry and deployment in Europe, while ensuring that the European market can remain competitive at global scale. A strong supporter of the European sustainability agenda, RECHARGE participates with strong evidence and industry knowledge in the respective institutional work programs to help establish a regulatory framework that will enable European actors to execute on the technological, environmental and social leadership ambitions of the Strategic Action Plan on Batteries. To this end, we need: • INTERNATIONAL LEVEL PLAYING FIELD: Ensure a level-playing field for the European battery industry by providing legislation supportive of the European Battery Alliance and the Strategic Action Plan for Batteries. -

Rates 2017.Xlsx

Facilities with Scales - Schedule of Charges March 2017 Description Charges GENERAL Basic Gate Fee $50 per ton Minimum Gate Fee Charge for Waste $5.00 Recyclable Materials Drop Off No Charge TYPE OF MATERIAL HOUSEHOLD TRASH Up to 200 lbs. minimum Gate Fee $5.00 $0.50 each additional 20 lb. increment or fraction CONSTRUCTION AND DEMOLITION (C&D) C&D with no concrete, recyclables, green waste or chipable wood $50 per ton minimum $5.00 Separated Concrete $25 per ton minimum $5.00 Separated chipable wood $25 per ton minimum $5.00 Mixed C&D (household trash, recyclables, green waste and/or concrete in the load) $175 per ton minimum $5.00 GREEN WASTE Lawn Clippings/Leaves, Up to 400lbs. Minimum Gate Fee $5.00 yard waste, brush, shrubs, $.0.50 each additional 40lb. Increment or fraction trees, branches, woodchips. Tree Stumps $4.00 less than 24" plus Gate Fee $5.00 $12.00 greater than 24" plus Gate Fee $5.00 Mixed Debris (Green waste, household trash,recyclables and/or concrete in the load) $175 per ton minimum $5.00 ANIMALS Small (less than 25 lbs.) $5.00 each + $5.00 Gate Fee Medium (25-200 lbs.) $10.00 each + $5.00 Gate Fee Large (more than 200lbs.) $30.00 each + $5.00 Gate Fee FURNITURE $5.00 minimum Gate Fee plus $4.00 per item ELECTRONIC WASTE No Charge UNIVERSAL WASTE No Charge RESIDENTIAL HOUSEHOLD HAZARDOUS WASTE No Charge COMMERCIAL HAZARDOUS WASTE Not accepted SEPTAGE Inyo $65.00 first 3,000 gallons $42.00 per additional 1,000 gallons or increment Out of County $130.00 first $3,000 gallons $84.00 per addional 1,000 gallons or increment Facilities with Scales - Schedule of Charges March 2017 Description Charges TIRES Auto & light truck $4.00 for 19" rim or less + $5.00 Gate Fee $8.00 for 20" - 24.5" rim + $5.00 Gate Fee Tractor/Heavy Equipment Tire $30 For Up to 100 lbs + $5.00 Gate Fee $40 over 100 lbs. -

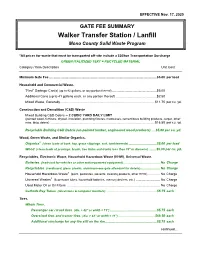

00 Gate Fee Schedule

EFFECTIVE Nov. 17, 2020 GATE FEE SUMMARY Walker Transfer Station / Lanfill Mono County Solid Waste Program *All prices for waste that must be transported off-site include a $20/ton Transportation Surcharge GREEN ITALICIZED TEXT = RECYCLED MATERIAL Category / Item Description Unit Cost Minimum Gate Fee ....................................................................................................................... $5.00 per load Household and Commercial Waste. “First” Garbage Can(s) (up to 82 gallons, or any portion thereof) .................................................. $5.00 Additional Cans (up to 41 gallons each, or any portion thereof) ............................................. $2.50 Mixed Waste, Generally ......................................................................................................... $11.75 per cu. yd. Construction and Demolition (C&D) Waste Mixed Building C&D Debris -- 2 CUBIC YARD DAILY LIMIT (painted wood, furniture, drywall, insulation, plumbing fixtures, mattresses, cementitious building products, carpet, other misc. bldg. debris) ..................................................................................................................... $16.50 per cu. yd. Recyclable Building C&D Debris (un-painted lumber, engineered wood products) …$5.00 per cu. yd. Wood, Green Waste, and Similar Organics. Organics8 (clean loads of bark, hay, grass clippings, sod, tumbleweeds) ............................... $5.00 per load Wood (clean loads of prunings, brush, tree limbs and trunks less than 18” -

Waste Batteries

Waste Batteries 16. September 2015 Dr. Michael Oberdörfer Overview 1. Introduction 2. European Battery Directive 2006/66 3. Implementation in German 4. Recovery technologies for waste batteries 2 1. Introduction Main chemical systems Primary batteries (not rechargeable) • Zinc-carbon • Alkaline-manganese • Lithium • Silver oxide; Zinc Air • Mercury-oxide Secondary batteries or accumulators (rechargeable) • Lead-acid • Lithium-Ion, Lithium-polymer • NiMH • NiCd 3 1. World-market Portable rechargeable 16% Primary batteries 37% Industrial rechargeable 17% Automotive batteries 30% 4 2. The Batteries Directive 2006/66/EC Aims: Prohibition on the placing on the market of batteries and accumulators containing hazardous substances. Promotion of a high level of collection and recycling of waste batteries and accumulators. What is new? Applies to all battery types Ban on mercury and cadmium Producer responsibility: collection schemes and recycling Collection targets and recycling efficiency 5 2. The Batteries Directive 2006/66/EC Definitions Portable battery: - is sealed and - can be hand-carried and - is neither an industrial nor an automotive battery. Industrial battery: - designed for exclusively industrial or professional uses or used in any type of electric vehicle. Automotive battery: - used for automotive starter, lighting or ignition power. Producer: - any person in a Member State that places batteries or accumulators, including those incorporated into appliances or vehicles, on the market for the first time within the territory -

Chapter 14 the Economics of Marine Litter

Chapter 14 The Economics of Marine Litter Stephanie Newman, Emma Watkins, Andrew Farmer, Patrick ten Brink and Jean-Pierre Schweitzer Abstract This chapter aims to provide an overview of research into quantifying the economic impacts of marine litter. From an environmental economics perspec- tive it introduces the difficulties in measuring the economic costs of marine litter; reviews those sectors where these costs are notable; and considers policy instru- ments, which can reduce these costs. Marine litter is underpinned by dynamic and complex processes, the drivers and impacts of which are multi-scalar, trans- boundary, and play out in both marine and terrestrial environments. These impacts include economic costs to expenditure, welfare and lost revenue. In most cases, these are not borne by the producers or the polluters. In industries such as fisher- ies and tourism the costs of marine litter are beginning to be quantified and are considerable. In other areas such as impacts on human health, or more intangible costs related to reduced ecosystem services, more research is evidently needed. As the costs of marine litter are most often used to cover removing debris or recov- ering from the damage which they have caused, this expenditure represents treat- ment rather than cure, and although probably cheaper than inaction do not present a strategy for cost reduction. Economic instruments, such as taxes and charges addressing the drivers of waste, for instance those being developed for plastic bags, could be used to reduce the production of marine litter and minimise its impacts. In any case, there remain big gaps in our understanding of the harm caused by marine litter, which presents difficulties when attempting to both quantify its economic costs, and develop effective and efficient instruments to reduce them. -

Overview of Industrial Waste Management

Overview of Industrial Waste Management Ajith de Alwis Chemical and Process Engineering Office of Science Technology and Innovation I N D Public Solid U Non W Hazardous S T PPP A R Y S Liquid B Private T A C E Hazardous K B Air O N E New Industries and Infrastructure • Ports and related infrastructure • Airports • Highways • Power stations – Coal • Industrial Estates • Export led manufacturing industries • Food Processing • Mineral Processing and Value Addition • Tourism • Urban growth - Metros • Nanoscience Park • Off shore Oil Exploration Analysis • Policy Aspects • Regulatory Environment • Human Resources Availability • Planning Aspects • Technology Aspects • Industry Mentality • Market requirements • Stakeholder requirements Policy Goals 1. Achieve Sustainable Development in Sri Lanka 2. Improve Environmental Quality throughout Sri Lanka 3. Improve eco-efficiency across all sectors of the economy in Sri Lanka 4. Alleviate Poverty and Improve the Living standards of all Sri Lankans 6 Prescribed Projects Approach to Environmental Protection Extreme Moderate No Change Change Change Government Authoritarian more than civil environmentalism society Government Moderate and Civil Environmentalism Society Civil Society Corporate Anti more than Environmentalism environmentalism Government EPL 6980 industries without an EPL Lankadeepa Oct 11, 2011 Illegal Dumping Due Diligence & LC Responsibility …. A Structural Failure ! BOARD OF DIRECTORS CHAIRMAN FINANCE DIRECTOR ACCOUNTANT GENERAL MANAGER CLERKS PRODUCTION & ADMINISTRATION MANAGER PROCESS -

Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: a Technical Guide on Waste-To-Energy Initiatives

WIEGO Technical Brief No 11 August 2019 Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: A Technical Guide on Waste-to-Energy Initiatives Jeroen IJgosse WIEGO Technical Briefs The global research-policy-action network Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Technical Briefs provide guides for both specialized and nonspecialized audiences. These are designed to strengthen understanding and analysis of the situation of those working in the informal economy as well as of the policy environment and policy options. About the Author: Jeroen IJgosse is a senior international solid waste management advisor, an urban environmental specialist, trainer and process facilitator with 25 years of experience in solid waste management in Latin America, Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe. He has worked extensively in the fields of planning, process facilitation, institutional strengthening, policy development, financial issues, due diligence assessment and inclusive processes involving informal actors in solid waste management. After 20 years living and working in Latin America, he currently resides in the Netherlands. Publication date: August, 2019 ISBN number: 978-92-95106-36-9 Please cite this publication as: IJgosse, Jeroen. 2019. Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: A Technical Guide on Waste-to-Energy Initiatives. WIEGO Technical Brief No. 11. Manchester, UK: WIEGO. Series editor: Caroline Skinner Copy editor: Megan MacLeod Layout: Julian Luckham of Luckham Creative Cover photo: Waste pickers working at the Kpone Landfill in Tema, Ghana face the threat of losing access to waste for recycling. Photo: Dean Saffron Published by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) A Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee – Company No. 6273538, Registered Charity No. -

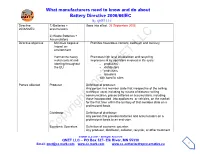

Directive 2006/66/EC by QNET LLC Directive 1) Batteries + Goes Into Effect 26 September 2008 2006/66/EC Accumulators

What manufacturers need to know and do about Battery Directive 2006/66/EC By QNET LLC Directive 1) Batteries + Goes into effect 26 September 2008 2006/66/EC accumulators 2) Waste Batteries + Accumulators Directive objective Minimize negative Prohibits hazardous content: cadmium and mercury impact on environment Harmonize heavy Promotes high level of collection and recycling metal content and Improvement by operators involved in life cycle: labeling throughout - producers the EU. - distributors - end-users - recyclers with specific rules Parties affected Producer Definition of producer: Any person in a member state that irrespective of the selling technique used, including by means of distance selling communication, places batteries or accumulators, including those incorporated into appliances or vehicles, on the market for the first time within the territory of that member state on a professional basis Distributor Definition of distributor: Any person that provides batteries and accumulators on a professional basis to an end-user. Economic Operators Definition of economic operator: Any producer, distributor, collector, recycler, or other treatment © QNET LLC 2007 – All Rights Reserved QNET LLC – PO Box 527- Elk River, MN 55330 Email: [email protected] www.ce-mark.com www.ce-authorizedrepresentative.eu 1 What manufacturers need to know and do about Battery Directive 2006/66/EC A Doing It Once! service By QNET LLC operator. Member States Definition of member states: All EU countries Directive scope All types of batteries and Regardless of shape, volume, weight, material composition or accumulators. Includes: use. Battery or accumulators Exemptions: Battery packs - Equipment connected with the protection of Portable battery Member States essential security interests, arms, Button cell munitions, and war material, with the exclusion of Automotive battery products that are not intended for specifically Industrial battery military purposes. -

Energy Recovery from Sewage Sludge: the Case Study of Croatia

energies Article Energy Recovery from Sewage Sludge: The Case Study of Croatia Dinko Đurđevi´c 1,* , Paolo Blecich 2 and Željko Juri´c 1 1 Energy Institute Hrvoje Požar, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Engineering, University of Rijeka, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 April 2019; Accepted: 16 May 2019; Published: 20 May 2019 Abstract: Croatia produced 21,366 tonnes of dry matter (DM) sewage sludge (SS) in 2016, a quantity expected to surpass 100,000 tonnes DM by 2024. Annual production rates for future wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) in Croatia are estimated at 5.8–7.3 Nm3/people equivalent (PE) for biogas and 20–25 kgDM/PE of sewage sludge. Biogas can be converted into 12–16 kWhel/PE of electricity and 19–24 kWhth/PE of heat, which is sufficient for 30–40% of electrical and 80–100% of thermal autonomy. The WWTP autonomy can be increased using energy recovery from sewage sludge incineration by 60% for electricity and 100% of thermal energy (10–13 kWhel/PE and 30–38 kWhth/PE). However, energy for sewage sludge drying exceeds energy recovery, unless solar drying is performed. 2 The annual solar drying potential is estimated between 450–750 kgDM/m of solar drying surface. The lower heating value of dried sewage sludge is 2–3 kWh/kgDM and this energy can be used for assisting sludge drying or for energy generation and supply to WWTPs. Sewage sludge can be considered a renewable energy source and its incineration generates substantially lower greenhouse gases emissions than energy generation from fossil fuels. -

CERTIFICATE of COMPLIANCE Battery Directive

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE with EU Battery Directive 2006/66/EC from 6 September 2006 and its amendment (Dir. 2008/12/EC, 2008/103/EC, 2013/56/EU) Renata SA's range of 3V Lithium Manganese Dioxide coin cells: Renata CR1025 1) Renata CR2016.MFR 8) Renata CR2320 1) Renata CR1216 1) Renata CR2025 MFR 2) Renata CR2325 1) Renata CR1216 MFR 6) Renata CR2025 1) Renata CR2430 1) Renata CR1220 1) Renata CR2032 MFR 2) Renata CR2430 MFR 5) Renata CR1220 MFR 6) Renata CR2032 1) Renata CR2450N 1) Renata CR1225 1) Renata CR2032.MFR 10) Renata CR2450N.MFR 11) Renata CR1616 1) Renata CR2045 3) Renata CR2450HT 4) Renata CR1620 1) Renata CR2025.MFR 9) Renata CR2477N 1) Renata CR1632 1) Renata CR2045HT 4) Renata CR2450N-MFR 7) Renata CR2016 MFR 2) Renata CR2046A 4) Renata CR2477N.MFR 12) Renata CR2016 1) This document certifies that the battery models as stated above and provided by Renata SA are in compliance with the above mentioned EU Battery Directive. January 11, 2021 Eric Weber CTO Weight limits according to 2006/66/EC Substance Weight limit (ppm) Lead (Pb) 40 Cadmium (Cd) 20 Mercury (Hg) 5 1) SGS Test Report EC405623000 dated Feb 16, 2007 2) SGS Test Report EC405697500 dated March 14, 2007 3) SGS Test Report CANEC0904976701 dated October 12, 2009 4) SGS Test Report CANEC0904976702 dated October 12, 2009 5) SGS Test Report CE/2009/45328 dated April 22, 2009 6) SGS Test Report CE/2013/72260 dated September 2, 2013 7) CTI Test Report RLSZD001049480001 dated October 10, 2011 8) CTI Test Report SCL01H064838001 9) CTI Test Report SCL01H064838002 10) CTI Test Report SCL01H064838003 11) CTI Test Report SCL01H064838004 12) CTI Test Report SCL01H064838005 Applicability of RoHS / WEEE / End of Life Vehicles Directives on Batteries: • The RoHS Directive Directive 2011/65/EU (including amendment 2015/863/EU) of the European Parliament and of the Council of June 08, 2011 on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronics equipment (RoHS Directive).