Insights from Women About Drinking Alcohol During Pregnancy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning Your Breech Baby to a Head-Down Position (External Cephalic Version)

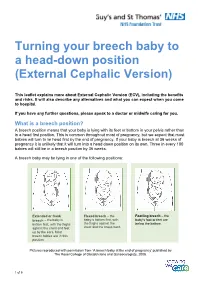

Turning your breech baby to a head-down position (External Cephalic Version) This leaflet explains more about External Cephalic Version (ECV), including the benefits and risks. It will also describe any alternatives and what you can expect when you come to hospital. If you have any further questions, please speak to a doctor or midwife caring for you. What is a breech position? A breech position means that your baby is lying with its feet or bottom in your pelvis rather than in a head first position. This is common throughout most of pregnancy, but we expect that most babies will turn to lie head first by the end of pregnancy. If your baby is breech at 36 weeks of pregnancy it is unlikely that it will turn into a head down position on its own. Three in every 100 babies will still be in a breech position by 36 weeks. A breech baby may be lying in one of the following positions: Extended or frank Flexed breech – the Footling breech – the breech – the baby is baby is bottom first, with baby’s foot or feet are bottom first, with the thighs the thighs against the below the bottom. against the chest and feet chest and the knees bent. up by the ears. Most breech babies are in this position. Pictures reproduced with permission from ‘A breech baby at the end of pregnancy’ published by The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2008. 1 of 5 What causes breech? Breech is more common in women who are expecting twins, or in women who have a differently-shaped womb (uterus). -

Maternal Movement and Position Changes to Facilitate Labor Progress Have Been Discussed in the Literature for Decades

ELAINE ZWELLING, PHD, RN, LCCE, FACCE Abstract The benefi ts of maternal movement and position changes to facilitate labor progress have been discussed in the literature for decades. Recent routine interventions such as amniotomy, induction, fetal monitoring, and epidural anesthesia, as well as an increase in maternal obesity, have made position changes during labor challenging. The lack of maternal changes in position throughout labor can contribute to dystocia and increase the risk of cesarean births for failure to progress or descend. This article provides a historical review of the research fi ndings related to the effects of maternal positioning on the labor process and uses six physiological principles as a framework to offer sug- gestions for maternal positioning both before and after epidural anesthesia. Key Words Birth; Childbirth; Labor, fi rst stage; Labor, second stage; Maternity nursing; Obstetrical nursing; Maternal postures; Maternal positioning. Overcoming the Challenges: Maternal Movement 72 volume 35 | number 2 March/April 2010 or centuries laboring women chose to remain dural anesthesia, found that women who were able to mobile and upright, using positions such as change positions regularly or maintain upright positions standing, sitting, kneeling, hands and knees, or during labor were more comfortable and required less Fsquatting (Gupta & Nikodem, 2000; Johnson, pain medication (Atwood, 1976; de Jong et al., 1997; En- Johnson, & Gupta, 1991). Today immobility throughout gelmann, 1977; Johnson et al., 1991). For instance, Ada- the labor process has become a common occurrence for chi, Shimada, and Usul (2003) found in their study of 58 many childbearing women. Increased medical manage- laboring women that a sitting position decreased labor ment, obesity, lack of patient understanding about the pain in contrast with supine positioning. -

Variation in Fetal Presentations and Positions Among Women in Warri, Delta State, Nigeria

World Research Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology ISSN: 2277-6001, Volume 2, Issue 1, 2013, pp.-10-12. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000126 VARIATION IN FETAL PRESENTATIONS AND POSITIONS AMONG WOMEN IN WARRI, DELTA STATE, NIGERIA OLANIYAN O.T.1*, MERAIYEBU A.B.1, ALELE J.Y.1, DARE J.B.2, ATSUKWEI D.1 AND ADELAIYE A.B.1 1Department of Physiology, Bingham University, Karu, Nasarawa, Nigeria. 2Department of Anatomy, Bingham University, Karu, Nasarawa, Nigeria. *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: November 21, 2013; Accepted: December 23, 2013 Abstract- This study investigates the various fetal presentations among women in Warri and the various predisposing factors which may have possibly brought about these variations; the major positions considered were cephalic, breech and transverse, with the considered influencing factors being gestational age of the fetus, maternal age, amniotic fluid volume, parity, and method of previous deliveries. A total of 105 ultra- sound fetal biometries with a total of 108 fetuses, between 15-40 weeks of gestational age, and maternal age between 19 and 40 were used for this study. Fetal ultrasound biometry was used to find out information about the fetus including gestational age, amniotic fluid volume, presentation of the fetus and a questionnaire was used to take information about the mother including maternal age, parity, and method of previous delivery (ies). The result showed that a total of 82 fetuses (75.9%) were Cephalic babies, 19 (17.6%) were Breech and 7 (6.5%) are transverse. Out of the 105 women, there were 102 (77.1% cephalic, 18.3% breech, 4.8% transverse) women with adequate amniotic fluid volume and 1 woman (with a cephalic fetus) with average amniotic fluid volume and 2 women (with transverse foetuses) with low amniotic fluid volume. -

Module Presentation

Module Presentation How to best use the Modules To make the best use of this training we encourage you to complete each Module in order following the format below: 1. Read Module Presentation. Added explanations can be found in the HELPER Guidelines and in the extra information section if there is one. 2. Complete the Extraction/Scenario training exercises. The extraction exercises use de-identified and altered patient medical records. Enter the requested information into the provided section from the Birth Certificate Workbook. The Scenarios are situations you may encounter as you collect information from your patients’ medical records. 3. Check your responses using the answer sheets immediately following the segment completed 4. Complete the Module specific Evaluation, as before the answers are immediately following the Evaluation 5. If not already done, read extra training materials, if available. If you have questions about how to answer any of the requests for information in the NYS Certification of Live Birth Training Modules, please contact Rosemary Varga (585-275-8737). *”Coding” is a convenient although slightly misleading term for entering the needed information in the Statewide Perinatal Data system. True “coding” is the entry of predetermined numbers into a system that can then rate the material. We do not use numbers rather we enter the requested information. Module Three Labor & Delivery Part I Labor & Delivery Fields •Labor & Delivery information is found in the mother’s chart with much of the information on the L & D flowsheet/summary. A copy of this information may also be found in the infant’s chart. 2 Mother Transferred in Antepartum •Only complete these fields if the mother was transferred for medical reasons NYS GUIDELINES 3 Mother’s Weight at Delivery •Mother’s weight at delivery will often be found on the L&D flowsheet If you can’t find mother’s weight at delivery in the L&D information you can use the mother’s weight at her last prenatal visit if the visit was within 2 weeks of delivery. -

Reducing Alcohol Use During Pregnancy Saves Lives

WICWORKS REDUCING ALCOHOL USE DURING PREGNANCY SAVES LIVES women drink no alcohol at all if pregnant or planning to become pregnant.7 Low-income women, whose children are most at risk for negative health outcomes, are less likely to receive appropriate counseling regarding alcohol use in pregnancy.8.9 The Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) serves more than 9 million low-income participants each month, including more than half of all infants born in the United States.10 Given its reach into a high- risk population during this critical period of the life nfants exposed to alcohol before birth can cycle, WIC can play a major role in reducing alcohol have serious life-long problems. WIC is in consumption during pregnancy. Along with food and Ian excellent position to screen pregnant nutrition education, WIC agencies are mandated by women for alcohol use during pregnancy and federal law to provide individual screening for drug and help women change their drinking behaviors. alcohol use and to make referrals to substance abuse In collaboration with UCLA, the largest local treatment programs when needed.11 The challenge with agency WIC program in the country designed such screening and referral is that only heavy users of and conducted a randomized study of a brief alcohol qualify for substance abuse treatment programs, intervention program to reduce prenatal yet lower levels of alcohol use can also be harmful to the alcohol use among WIC participants. Results developing fetus. Until now, WIC screening has often documented that brief intervention conducted led to recognition of prenatal alcohol use—with no in the WIC setting led to significant reductions accompanying intervention tools available. -

Breech Presentation at the End of Your Pregnancy

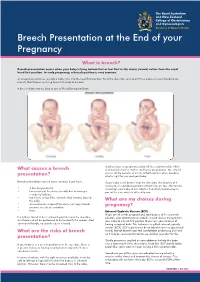

Breech Presentation at the End of your Pregnancy What is breech? Breech presentation occurs when your baby is lying bottom first or feet first in the uterus (womb) rather than the usual head first position. In early pregnancy, a breech position is very common. As pregnancy continues, usually a baby turns into the head first position. Near the due date, only about three babies in every hundred are breech. Most babies are lying head first ready to be born. A breech baby may be lying in one of the following positions: In other cases a caesarean section will be recommended, which What causes a breech also has risks for the mother and future pregnancies. You should discuss all the benefits and risks of both options when deciding presentation? what is right for you and your baby. Breech presentation may be more common if you have: If your baby is still breech near the due date, the chances of it turning to a head down position without help are low. Attempts to • a low-lying placenta encourage your baby to turn into the head first position may be • lax muscles of the uterus (usually due to having a part of the care which is offered to you. number of babies) • too much, or too little, amniotic fluid (waters) around the baby What are my choices during • an uncommon shape of the uterus, or large fibroids pregnancy? • previous breech presentation • twins External Cephalic Version (ECV) If you are 36 weeks pregnant and your baby is still in a breech If a baby is found to be in a breech position near the due date, position, your obstetrician or midwife should discuss trying to turn an ultrasound will be performed to try to identify the reason. -

Nonstress Test and Contraction Stress Test - Uptodate

2019/3/14 Nonstress test and contraction stress test - UpToDate Official reprint from UpToDate® www.uptodate.com ©2019 UpToDate, Inc. and/or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved. Nonstress test and contraction stress test Author: David A Miller, MD Section Editor: Charles J Lockwood, MD, MHCM Deputy Editor: Vanessa A Barss, MD, FACOG All topics are updated as new evidence becomes available and our peer review process is complete. Literature review current through: Feb 2019. | This topic last updated: Jan 16, 2018. INTRODUCTION Fetal health is evaluated, in part, by assessment of fetal heart rate (FHR) patterns. The primary goal is to identify fetuses at risk of intrauterine death or neonatal complications and intervene (often by delivery) to prevent these adverse outcomes, if possible. The nonstress test (NST) and the contraction stress test (CST) are used for antepartum FHR testing. An abnormal test (nonreactive NST, positive CST) is sometimes associated with adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes, while a normal test (reactive NST, negative CST) is usually associated with a neurologically intact and adequately oxygenated fetus. When interpreting these tests, the clinician needs to account for gestational age, prior results of fetal assessment, maternal conditions (including medications), and fetal condition (eg, growth restriction, anemia, arrhythmia). The NST and CST will be reviewed here. Intrapartum fetal evaluation and additional techniques for assessing fetal health are discussed separately. ● (See "Intrapartum fetal heart rate assessment".) ● (See "The fetal biophysical profile".) ● (See "Decreased fetal movement: Diagnosis, evaluation, and management".) ● (See "Doppler ultrasound of the umbilical artery for fetal surveillance".) PHYSIOLOGIC BASIS OF FETAL HEART RATE CHANGES Physiologic development of the fetal heart occurs across gestation and affects fetal heart rate (FHR) patterns. -

Time of Quickening Is Associated with the Placental Site and BMI in Nulliparous Women Negin Jaafar 1 Lars Henning Pedersen 2,3,4

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.27.20239665; this version posted November 30, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Time of quickening is associated with the placental site and BMI in nulliparous women Negin Jaafar 1 Lars Henning Pedersen 2,3,4 Olav Bjørn Petersen 2,3,5,6 Lone Hvidman 2,3 1 Aarhus University Hospital, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Palle Juul- Jensens Boulevard 99, DK-8200 Aarhus N, Denmark. 2 Aarhus University Hospital, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Palle Juul- Jensens Boulevard 99, DK-8200 Aarhus N, Denmark. 3 Aarhus University, Department of Clinical Medicine, Palle Juul-Jensens Boulevard 82, DK-8200 Aarhus N, Denmark. 4 Aarhus University Hospital, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Bartolins Alle, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark. 5 Copenhagen University Hospital Rigshospitalet, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Blegdamsvej 9, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark 6 University of Copenhagen, Nørregade 10, DK-1165 Copenhagen, Denmark Corresponding author: Lars Henning Pedersen [email protected] NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.27.20239665; this version posted November 30, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Breech Or Cephalic Presentation

VU Research Portal Fetal breech presentation: impact on perinatal posture and locomotion Fong, B.F. 2009 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Fong, B. F. (2009). Fetal breech presentation: impact on perinatal posture and locomotion: A longitudinal study. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 1 1 General introduction General introduction 11 In the Netherlands, about 190.000 live births occur every year [1]. Of these children the vast majority is born in cephalic presentation, which means with the head first. Breech presentation is defined as the presentation in which the fetal head is positioned in the fundus (the upper part of the uterus) and the fetal buttocks are facing toward the maternal cervix. -

The Association Between Fetal Position at the Onset of Labour and Birth Outcomes

THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN FETAL POSITION AT THE ONSET OF LABOUR AND BIRTH OUTCOMES by Aishah Ahmad (Nee Bibi) A thesis submitted to: The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Public Health and Epidemiology Medical School The University of Birmingham August 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Fetal position throughout labour exerts considerable influence on labour and delivery, with a mal-positioned fetus during active labour known to contribute towards fetal and maternal morbidity. In response there is a move towards promoting the Left Occipito-Anterior (LOA) position at labour onset as optimal. It is thought that the LOA position encourages anterior rotation thus reducing the likelihood of mal-rotation. A systematic review was undertaken which highlighted an absence of scientific evidence. A prospective cohort study was therefore conducted with 1250 nulliparous women who were scanned to accurately determine fetal position, specifically the LOA position at the onset of labour and the association with delivery mode and other birth outcomes was examined. The LOA position at the onset of labour was not associated with mode of delivery, nor were any of the other positions (p=0.39). -

Postpartum Care for the Mother and Newborn

ABSTRACT This document reports the outcomes of a technical consultation on the full range of issues relevant to the postpartum period for the mother and the newborn. The report takes a comprehensive view of maternal and newborn needs at a time which is decisive for the life and health both of the mother and her newborn. Taking women’s own perceptions of their own needs during this period as its point of departure, the text examines the major maternal and neonatal health challenges, nutrition and breastfeeding, birth spacing, immunization and HIV/AIDS before concluding with a discussion of the crucial elements of care and service provision in the postpartum. The text ends with a series of recommendations for this critical but under-researched and under-served period of the life of the woman and her newborn, together with a classification of common practices in the postpartum into four categories: those which are useful, those which are harmful, those for which insufficient evidence exists and those which are frequently used inappropriately. WHO/RHT/MSM/98.3 Dist.: General Orig.: English CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................1 1 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................6 1.1 Preamble ............................................................................................................6 1.2 Background........................................................................................................7 -

OP, Brow & Face Presentations

OP, Brow & Face Presentations Study Group Module OP, Brow & Face Presentations National Midwifery Institute, Inc. Study Group Coursework Syllabus Description: This module explores the malpresentations of OP, face & brow and midwifery management in labor. It includes recommended reading materials in print and online, and asks students to complete short answer questions for assessment, long answer questions for deeper reflection, and learning activities/projects to deepen your hands-on direct application of key concepts. Learning Objectives: ● Understand the relationship between the baby’s head and the pelvis when the baby is in the Occiput Posterior (OP), Brow and Face cephalic presentations. ● Understand the likely resolution of Brow and Face cephalic presentations in birth. ● Identify when and how OP position is problematic. ● Differentiate between truly problematic aspects of OP positions and the holistic approach to OP as a variation of normal birth. ● Understand when the expertise of a midwife can be of benefit during an OP labor and identify a variety of support techniques and holistic methods to apply when appropriate. ● Identify head molding in the infant and the corresponding cephalic presentations. ● Identify the long arc and short arc rotations of the fetal head in the pelvis. ● Identify and demonstrate the cardinal movements of birth in OP, Brow and Face cephalic presentations. ● Review First Stage Labor and Second Stage Labor modules Learning Activities: ● Research and read appropriate study sources, seeking out additional study sources where needed ● Complete short answer questions in attached module document for assessment ● Complete long answer questions for deeper reflection in attached module document for assessment ● Complete learning activities listed in attached module document for assessment ○ Write a reflection paragraph on the experience of practicing the movements of OP, Face and Brow © National Midwifery Institute, Inc.