Breech Or Cephalic Presentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Diagnostic Impact of Limited, Screening Obstetric Ultrasound When Performed by Midwives in Rural Uganda

Journal of Perinatology (2014) 34, 508–512 © 2014 Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved 0743-8346/14 www.nature.com/jp ORIGINAL ARTICLE The diagnostic impact of limited, screening obstetric ultrasound when performed by midwives in rural Uganda JO Swanson1, MG Kawooya2, DL Swanson1, DS Hippe1, P Dungu-Matovu2 and R Nathan1 OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the diagnostic impact of limited obstetric ultrasound (US) in identifying high-risk pregnancies when used as a screening tool by midwives in rural Uganda. STUDY DESIGN: This was an institutional review board-approved prospective study of expecting mothers in rural Uganda who underwent clinical and US exams as part of their standard antenatal care visit in a local health center in the Isingiro district of Uganda. The midwives documented clinical impressions before performing a limited obstetric US on the same patient. The clinical findings were then compared with the subsequent US findings to determine the diagnostic impact. The midwives were US-naive before participating in the 6-week training course for limited obstetric US. RESULT: Midwife-performed screening obstetric US altered the clinical diagnosis in up to 12% clinical encounters. This diagnostic impact is less (6.7 to 7.4%) if the early third trimester diagnosis of malpresentation is excluded. The quality assurance review of midwives’ imaging demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosing gestational number, and 90% sensitivity and 96% specificity in the diagnosis of fetal presentation. CONCLUSION: Limited, screening obstetric US performed by midwives with focused, obstetric US training demonstrates the diagnostic impact for identifying conditions associated with high-risk pregnancies in 6.7 to 12% of patients screened. -

Breech Presentation at Delivery: a Marker for Congenital Anomaly?

Journal of Perinatology (2014) 34, 11–15 & 2014 Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved 0743-8346/14 www.nature.com/jp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Breech presentation at delivery: a marker for congenital anomaly? D Mostello1, JJ Chang2, F Bai2, J Wang3, C Guild4, K Stamps2 and TL Leet2,{ OBJECTIVE: To determine whether congenital anomalies are associated with breech presentation at the time of birth. STUDY DESIGN: A population-based, retrospective cohort study was conducted among 460 147 women with singleton live births using the Missouri Birth Defects Registry, which includes all defects diagnosed during the first year of life. Maternal and obstetric characteristics and outcomes between breech and cephalic presentation groups were compared using w2-square statistic and Student’s t-test. Multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). RESULT: At least one congenital anomaly was more likely present among infants breech at birth (11.7%) than in those with cephalic presentation (5.1%), whether full-term (9.4 vs 4.6%) or preterm (20.1 vs 11.6%). The relationship between breech presentation and congenital anomaly was stronger among full-term births (aOR 2.09, CI 1.96, 2.23, term vs 1.40, CI 1.26, 1.55, preterm), but not in all categories of anomalies. CONCLUSION: Breech presentation at delivery is a marker for the presence of congenital anomaly. Infants delivered breech deserve special scrutiny for the presence of malformation. Journal of Perinatology (2014) 34, 11–15; -

A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of This Document Is Made Possible by Financial Contributions from Health Canada and Provincial and Territorial Governments

ICD-10-CA | CCI A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of this document is made possible by financial contributions from Health Canada and provincial and territorial governments. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada or any provincial or territorial government. Unless otherwise indicated, this product uses data provided by Canada’s provinces and territories. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be reproduced unaltered, in whole or in part and by any means, solely for non-commercial purposes, provided that the Canadian Institute for Health Information is properly and fully acknowledged as the copyright owner. Any reproduction or use of this publication or its contents for any commercial purpose requires the prior written authorization of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Reproduction or use that suggests endorsement by, or affiliation with, the Canadian Institute for Health Information is prohibited. For permission or information, please contact CIHI: Canadian Institute for Health Information 495 Richmond Road, Suite 600 Ottawa, Ontario K2A 4H6 Phone: 613-241-7860 Fax: 613-241-8120 www.cihi.ca [email protected] © 2018 Canadian Institute for Health Information Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre Guide de codification des données en obstétrique. Table of contents About CIHI ................................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. -

Twin Pregnancy with Triploidy and Co-Existing Live Twin Progressing to Viability: Case Study and Literature Review

Obstetrics & Gynecology International Journal Case Report Open Access Twin pregnancy with triploidy and co-existing live twin progressing to viability: Case study and literature review Abstract Volume 9 Issue 4 - 2018 Background: Twin pregnancies consisting of a triploid fetus with molar change and a 1,2 1,2 1,2 healthy coexisting fetus is an extremely rare phenomenon. Triploidy rarely advances to the Cingiloglu P, Yeung T, Sekar R second trimester, most resulting in a miscarriage, termination or stillbirth. Only five cases 1Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Women’s and Newborn of a triploid fetus and a healthy co-twin have been reported in literature. We present the first Services, Australia documented case of a live delivery of both triploid fetus and coexisting viable twin. 2University of Queensland, Australia Case presentation: A 23-year old woman, gravida 2, para 1 was admitted at 26+4 weeks Correspondence: Pinar Cingiloglu, Women’s and Newborn gestation with DCDA twins and a shortened cervix. Sonography revealed polyhydramnios, Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Bowen Bridge an abnormal cystic placenta, and small aortic valve for the presenting twin. Emergency Road&, Butterfield St, Herston Queensland Australia, Tel +61 caesarean section was performed at 28 weeks gestation for cord prolapse. Twin A was born (07) 3646 8111, Email [email protected] a live infant with ambiguous genitalia, syndactyly, epicanthic folds and cerebral cysts. Twin B was born a healthy live male. Histopathology revealed features consistent with Received: June 13, 2018 | Published: July 13, 2018 partial hydatidiform mole, and cytogenetics revealed a diandric triploidy in twin A. -

Turning Your Breech Baby to a Head-Down Position (External Cephalic Version)

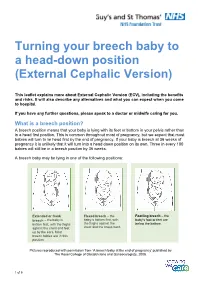

Turning your breech baby to a head-down position (External Cephalic Version) This leaflet explains more about External Cephalic Version (ECV), including the benefits and risks. It will also describe any alternatives and what you can expect when you come to hospital. If you have any further questions, please speak to a doctor or midwife caring for you. What is a breech position? A breech position means that your baby is lying with its feet or bottom in your pelvis rather than in a head first position. This is common throughout most of pregnancy, but we expect that most babies will turn to lie head first by the end of pregnancy. If your baby is breech at 36 weeks of pregnancy it is unlikely that it will turn into a head down position on its own. Three in every 100 babies will still be in a breech position by 36 weeks. A breech baby may be lying in one of the following positions: Extended or frank Flexed breech – the Footling breech – the breech – the baby is baby is bottom first, with baby’s foot or feet are bottom first, with the thighs the thighs against the below the bottom. against the chest and feet chest and the knees bent. up by the ears. Most breech babies are in this position. Pictures reproduced with permission from ‘A breech baby at the end of pregnancy’ published by The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2008. 1 of 5 What causes breech? Breech is more common in women who are expecting twins, or in women who have a differently-shaped womb (uterus). -

Gtg-No-20B-Breech-Presentation.Pdf

Guideline No. 20b December 2006 THE MANAGEMENT OF BREECH PRESENTATION This is the third edition of the guideline originally published in 1999 and revised in 2001 under the same title. 1. Purpose and scope The aim of this guideline is to provide up-to-date information on methods of delivery for women with breech presentation. The scope is confined to decision making regarding the route of delivery and choice of various techniques used during delivery. It does not include antenatal or postnatal care. External cephalic version is the topic of a separate RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 20a: ECV and Reducing the Incidence of Breech Presentation. 2. Background The incidence of breech presentation decreases from about 20% at 28 weeks of gestation to 3–4% at term, as most babies turn spontaneously to the cephalic presentation. This appears to be an active process whereby a normally formed and active baby adopts the position of ‘best fit’ in a normal intrauterine space. Persistent breech presentation may be associated with abnormalities of the baby, the amniotic fluid volume, the placental localisation or the uterus. It may be due to an otherwise insignificant factor such as cornual placental position or it may apparently be due to chance. There is higher perinatal mortality and morbidity with breech than cephalic presentation, due principally to prematurity, congenital malformations and birth asphyxia or trauma.1,2 Caesarean section for breech presentation has been suggested as a way of reducing the associated perinatal problems2,3 and in many countries in Northern Europe and North America caesarean section has become the normal mode of breech delivery. -

Advising Women with Diabetes in Pregnancy to Express Breastmilk In

Articles Advising women with diabetes in pregnancy to express breastmilk in late pregnancy (Diabetes and Antenatal Milk Expressing [DAME]): a multicentre, unblinded, randomised controlled trial Della A Forster, Anita M Moorhead, Susan E Jacobs, Peter G Davis, Susan P Walker, Kerri M McEgan, Gillian F Opie, Susan M Donath, Lisa Gold, Catharine McNamara, Amanda Aylward, Christine East, Rachael Ford, Lisa H Amir Summary Lancet 2017; 389: 2204–13 Background Infants of women with diabetes in pregnancy are at increased risk of hypoglycaemia, admission to a See Editorial page 2163 neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and not being exclusively breastfed. Many clinicians encourage women with See Comment page 2167 diabetes in pregnancy to express and store breastmilk in late pregnancy, yet no evidence exists for this practice. We Judith Lumley Centre, School of aimed to determine the safety and efficacy of antenatal expressing in women with diabetes in pregnancy. Nursing and Midwifery, La Trobe University, Methods We did a multicentre, two-group, unblinded, randomised controlled trial in six hospitals in Victoria, Australia. Melbourne, VIC, Australia (Prof D A Forster PhD, We recruited women with pre-existing or gestational diabetes in a singleton pregnancy from 34 to 37 weeks’ gestation A M Moorhead RM, and randomly assigned them (1:1) to either expressing breastmilk twice per day from 36 weeks’ gestation (antenatal L H Amir PhD); Royal Women’s expressing) or standard care (usual midwifery and obstetric care, supplemented by support from a diabetes educator). Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Randomisation was done with a computerised random number generator in blocks of size two and four, and was Australia (Prof D A Forster, A M Moorhead, S E Jacobs MD, stratified by site, parity, and diabetes type. -

Maternal Movement and Position Changes to Facilitate Labor Progress Have Been Discussed in the Literature for Decades

ELAINE ZWELLING, PHD, RN, LCCE, FACCE Abstract The benefi ts of maternal movement and position changes to facilitate labor progress have been discussed in the literature for decades. Recent routine interventions such as amniotomy, induction, fetal monitoring, and epidural anesthesia, as well as an increase in maternal obesity, have made position changes during labor challenging. The lack of maternal changes in position throughout labor can contribute to dystocia and increase the risk of cesarean births for failure to progress or descend. This article provides a historical review of the research fi ndings related to the effects of maternal positioning on the labor process and uses six physiological principles as a framework to offer sug- gestions for maternal positioning both before and after epidural anesthesia. Key Words Birth; Childbirth; Labor, fi rst stage; Labor, second stage; Maternity nursing; Obstetrical nursing; Maternal postures; Maternal positioning. Overcoming the Challenges: Maternal Movement 72 volume 35 | number 2 March/April 2010 or centuries laboring women chose to remain dural anesthesia, found that women who were able to mobile and upright, using positions such as change positions regularly or maintain upright positions standing, sitting, kneeling, hands and knees, or during labor were more comfortable and required less Fsquatting (Gupta & Nikodem, 2000; Johnson, pain medication (Atwood, 1976; de Jong et al., 1997; En- Johnson, & Gupta, 1991). Today immobility throughout gelmann, 1977; Johnson et al., 1991). For instance, Ada- the labor process has become a common occurrence for chi, Shimada, and Usul (2003) found in their study of 58 many childbearing women. Increased medical manage- laboring women that a sitting position decreased labor ment, obesity, lack of patient understanding about the pain in contrast with supine positioning. -

Variation in Fetal Presentations and Positions Among Women in Warri, Delta State, Nigeria

World Research Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology ISSN: 2277-6001, Volume 2, Issue 1, 2013, pp.-10-12. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000126 VARIATION IN FETAL PRESENTATIONS AND POSITIONS AMONG WOMEN IN WARRI, DELTA STATE, NIGERIA OLANIYAN O.T.1*, MERAIYEBU A.B.1, ALELE J.Y.1, DARE J.B.2, ATSUKWEI D.1 AND ADELAIYE A.B.1 1Department of Physiology, Bingham University, Karu, Nasarawa, Nigeria. 2Department of Anatomy, Bingham University, Karu, Nasarawa, Nigeria. *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: November 21, 2013; Accepted: December 23, 2013 Abstract- This study investigates the various fetal presentations among women in Warri and the various predisposing factors which may have possibly brought about these variations; the major positions considered were cephalic, breech and transverse, with the considered influencing factors being gestational age of the fetus, maternal age, amniotic fluid volume, parity, and method of previous deliveries. A total of 105 ultra- sound fetal biometries with a total of 108 fetuses, between 15-40 weeks of gestational age, and maternal age between 19 and 40 were used for this study. Fetal ultrasound biometry was used to find out information about the fetus including gestational age, amniotic fluid volume, presentation of the fetus and a questionnaire was used to take information about the mother including maternal age, parity, and method of previous delivery (ies). The result showed that a total of 82 fetuses (75.9%) were Cephalic babies, 19 (17.6%) were Breech and 7 (6.5%) are transverse. Out of the 105 women, there were 102 (77.1% cephalic, 18.3% breech, 4.8% transverse) women with adequate amniotic fluid volume and 1 woman (with a cephalic fetus) with average amniotic fluid volume and 2 women (with transverse foetuses) with low amniotic fluid volume. -

External Cephalic Version (Ecv) Author: Scope

Sponsor: Woman, Child and Youth Name: External Cephalic Version MATERNITY UNIT GUIDELINE: EXTERNAL CEPHALIC VERSION (ECV) AUTHOR: Consultant Obstetrician SCOPE: All obstetricians and midwives working in maternity. PURPOSE: To inform all health professions of the assessment criteria and procedure for an ECV. ECV is a procedure to rotate the fetus from a breech or transverse DEFINITIONS: presentation to a cephalic presentation by external manipulation of the mother’s abdomen INDICATIONS: Should be offered to women with a non-cephalic fetal lie to improve their chance of a vaginal cephalic birth ABSOLUTE Significant uterine anomaly (eg. bicornuate uterus); Indications for caesarean birth irrespective of fetal presentation; CONTRAINDICATIONS Antepartum haemorrhage; Placenta praevia; Severe maternal cardiac disease; Ruptured membranes (given risk of cord prolapse could be considered in theatre) Abnormal fetal monitoring suggestive of fetal hypoxia; Hyper-extended fetal head; Significant fetal anomaly (eg. hydrocephaly); Abruptio placenta; Fetal growth restriction (severe and/or abnormal dopplers); Multiple pregnancy – though may be considered for the second twin after birth of the first twin. RELATIVE Previous caesarean birth; CONTRAINDICATIONS Previous uterine surgery; Maternal obesity; Fetal growth restriction (mild with normal dopplers); Decreased liquor volume; Severe pregnancy induced hypertension; Established labour; Factors Decreasing Success Nulliparity Rates Anterior, lateral or cornual placenta Decreased amniotic -

Obstetrics Seventh Edition

PROLOGObstetrics seventh edition The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists WOMEN’S HEALTH CARE PHYSICIANS Obstetrics seventh edition Assessment Book The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists WOMEN’S HEALTH CARE PHYSICIANS ISBN 978-1-934984-22-2 Copyright 2013 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on the Internet, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 12345/76543 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 409 12th Street, SW PO Box 96920 Washington, DC 20090-6920 Contributors PROLOG Editorial and Advisory Committee CHAIR MEMBERS Ronald T. Burkman Jr, MD Bernard Gonik, MD Professor of Obstetrics and Professor and Fann Srere Chair of Gynecology Perinatal Medicine Tufts University School of Medicine Division of Maternal–Fetal Medicine Division of General Obstetrics and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Gynecology Department of Obstetrics and Wayne State University School of Gynecology Medicine Baystate Medical Center Detroit, Michigan Springfield, Massachusetts Louis Weinstein, MD Past Paul A. and Eloise B. Bowers Professor and Chair Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Thomas Jefferson University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Linda Van Le, MD Leonard Palumbo Distinguished Professor UNC Gynecologic Oncology University of North Carolina School of Medicine Chapel Hill, North Carolina PROLOG Task Force for Obstetrics, Seventh Edition COCHAIRS MEMBERS Vincenzo Berghella, MD Cynthia Chazotte, MD Director, Division of Maternal–Fetal Professor of Clinical Obstetrics and Medicine Gynecology and Women’s Health Professor, Department of Obstetrics Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Gynecology Weiler Hospital of the Albert Einstein Thomas Jefferson University College of Medicine Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Bronx, New York George A. -

Pretest Obstetrics and Gynecology

Obstetrics and Gynecology PreTestTM Self-Assessment and Review Notice Medicine is an ever-changing science. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapy are required. The authors and the publisher of this work have checked with sources believed to be reliable in their efforts to provide information that is complete and generally in accord with the standards accepted at the time of publication. However, in view of the possibility of human error or changes in medical sciences, neither the authors nor the publisher nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they disclaim all responsibility for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from use of the information contained in this work. Readers are encouraged to confirm the information contained herein with other sources. For example and in particular, readers are advised to check the prod- uct information sheet included in the package of each drug they plan to administer to be certain that the information contained in this work is accurate and that changes have not been made in the recommended dose or in the contraindications for administration. This recommendation is of particular importance in connection with new or infrequently used drugs. Obstetrics and Gynecology PreTestTM Self-Assessment and Review Twelfth Edition Karen M. Schneider, MD Associate Professor Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences University of Texas Houston Medical School Houston, Texas Stephen K. Patrick, MD Residency Program Director Obstetrics and Gynecology The Methodist Health System Dallas Dallas, Texas New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.